India’s Smart Cities Mission (SCM), launched in June 2015 and initially planned for five years, comes to a formal close in June 2024 after extensions. Nine years later, there is little public discourse about this flagship mission and hardly any mention by the Narendra Modi-led government.

Most of the 100 selected cities have spent or allocated the Mission’s funding across projects and interventions. The Centre gave each city a grant of Rs 500 crore while an equal amount came from state governments and urban local bodies (ULBs). Cities were also encouraged to raise their own funds, initiate public-private partnerships (PPPs), or converge with other missions and schemes to fund projects. According to the Mission dashboard[1], by May 10 this year, a total of 8,036 projects were underway or completed at a total cost of Rs 1,67,781crore. Nearly 1,000 projects are still under development, costing Rs 26,000 crore.

The Mission’s guidelines recommended two broad areas – area-based development and pan-city solutions based on Information and Communication Technology. The area-based development meant selecting a small portion of a city for redevelopment, retrofitting or green field projects for the majority of smart city interventions. Given that the Mission is now ending and the government is seeking a third term in office, it is a good time to reflect on the scheme which promised urban development and innovation to improve quality of life for urban residents and economic stability for local governments.

Photo: Smart Cities Mission Website

The Smart Cities Mission was launched at a time when the concept had already found popularity in the Global North and was rapidly spreading to cities across the Global South. While definitions, standards, and benchmarks have been vastly different – often absent – there are certain characteristics that make a city ‘smart’. Fundamentally, a smart city is one that uses and makes ubiquitous various digital technologies and collects a host of data. This helps it to manage its services and citizens, integrate and streamline urban services, and plan for the future.

While urban digitalisation did not begin with the smart city paradigm – either in India or in other parts of the world – the concept has sought to expand the scope of digitalisation through intertwined processes[2] of ‘platformisation, infrastructuring, and datafication’. Under the Smart Cities Mission, urban digitalisation has expanded significantly, if unevenly, in the 100 mission cities.

The smart city concept has been extensively critiqued for techno-solutionism and its dependence on technocrats, technology firms, and management consultants. Scholars and researchers have delved into the dangers and exclusions that come with code and algorithmic governance. The over dependence on and fetishization of digital technologies also led to these technologies as an end in itself rather than a means.

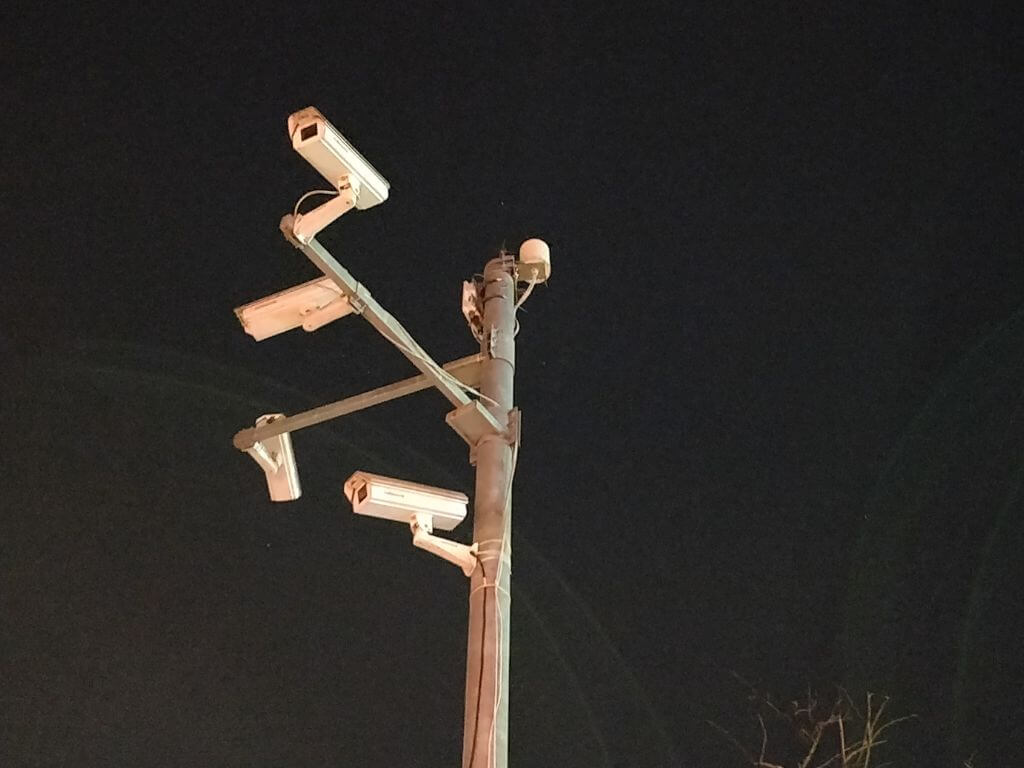

Further, problems are often framed around existing technology or are broken down into small and distinct portions instead of addressing complex and multifaceted urban issues. Smart cities run the risk of focusing on these interventions at the cost of other priorities and without paying adequate attention to issues of surveillance, access and the digital divide, data privacy, and exclusion of people from technological worlds—and in turn from the city itself.

While the Mission did not provide a definition for smart cities, it set out core principles for urban development – liveability, sustainability, and economic growth – besides a list of projects and interventions that the 100 cities should focus on, the governing structure to be adopted, and set aside Rs 2 lakh crore. Six focus areas were recommended – e-governance, water management, waste management, energy management, urban mobility, and skill development.

The area-based development has meant selecting a small portion of a city for redevelopment, retrofitting or green field projects for the majority of smart city interventions.

High focus on digitalisation

It is clear that digitalisation became an important part of the Smart Cities Mission over time. When the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MOHUA) published the guidelines, invited proposals from cities, and scored them to allocate funding, the focus was on the development of physical infrastructure concentrated in specific areas of the city under the area-based development.

Digitalisation was included under pan-city projects and included interventions like building an Integrated Command and Control Centre, installing various IoT devices and surveillance cameras, introducing an Integrated Traffic Management System, and smart water and electricity meters. An evaluation[3] of the first 60 proposals selected shows that most funding was earmarked for transport infrastructure, energy, water and sanitation, while only 3.7 percent was allocated for IT projects.

Early round-wise selection of cities between 2016 and 2018

| Round | No. of cities | Year of selection |

| Round I | 20 | January 2016 |

| Fast-Track Round | 13 | May 2016 |

| Round II | 27 | September 2016 |

| Round III | 30 | June 2017 |

| Round IV | 10 | January 2018* |

* Shillong (Meghalaya), the 100th smart city, was selected in June 2018

However, cities diverged from their proposals. The ministry also focused[4] on digitalisation and tried to steer the Mission towards conventional ideas of ‘smart’ by setting up data and analysis platforms. I have argued previously[5] that the Mission pivoted to focusing on digital interventions in 2019, led by the MOHUA.

For instance, all cities have built Integrated Command and Control Centres which are centralised panopticon-like structures that host various services which, through various internet-based technologies, can be viewed and controlled. This includes traffic management systems, CCTV cameras, environment sensors, municipal e-services, grievance redressal, waste management and surveillance systems, and the like. The ICCCs are also data centres. While all the 100 cities have set up ICCCs, they are at very different stages of development and digitalisation.

One of the initiatives taken by the ministry was to help cities assess their levels of data maturity by publishing the Data Maturity Assessment Framework (DMAF[6]) to create a baseline for digitalisation, guide them towards building a ‘data culture’, and assess their ‘data readiness’. Cities were ranked along five categories – beginner, initiator, explorer, enabled, and connected. The majority of the 100 cities, even in 2020, were still beginners.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

For example, Bhopal’s ICCC has three sections. One focuses on traffic management, violations of traffic rules, issuing of e-challans, and surveillance at various intersections. Another is dedicated to smart light poles with environmental sensors. The third collects and analyses data from other sources as well as oversees functions like waste management and smart parking. Bhopal is considered to be a ‘connected’ city. Quite different from this, Prayagraj, a ‘beginner’, is yet to install even basic sensors and software though the ICCC building has been built.

This discrepancy is for a host of reasons including levels of digitalisation before the launch of the Mission, priorities and budgets of these cities, and shifting goals through the duration of the Mission. However, there is also the aspect of the governance structure.

Corporate-style governance

When the Smart Cities Mission was launched, the guidelines argued that urban local bodies (ULBs) would not have the capacity or the expertise to implement the Mission and therefore mandated the setting up of Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs).

These, bypassing elected ULBs, would be empowered to plan, fund, implement, and appraise the smart city projects. They were constituted under the Special Companies Act, 2013, and were encouraged to emulate private corporations in their structures and decision-making processes. Importantly, these SPVs could choose who to hire as experts, employees, and vendors. They were headed by CEOs, usually IAS officers, and governed by a Board of Directors. This brought a corporate-management system to urban governance which disregarded elected representatives and local administration.

The exact composition of these SPVs has differed across cities—in some they have been treated by the existing city governments as conduits for Mission funding and administrative tasks while, in others, they have worked fairly independently focussing solely on smart city projects. For example, in Gujarat’s smart cities, the Deputy Municipal Commissioner of ULBs functions as CEO of the SPV and the two authorities work closely. In Pune, on the other hand, the SPV works more independently and focuses largely on projects confined to a specific area of the city selected for area-based development.

While there is near-universal agreement in the MOHUA and within the SPVs that this governance structure has aided faster decision-making, important questions arise about accountability and transparency in this SPV-isation of urban governance. These bodies depend heavily on management consultants for defining strategy, developing and floating tenders, outlining standard operating procedures, drafting policies, and coordinating among various agencies, especially when it comes to projects with a digital focus. There has been little involvement of the city’s elected officials; instead, bureaucrats do the heavy lifting on decisions.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

This undermined the role of elected bodies and created parallel power centres in urban governance which, in India, already suffered from the malaise of multiple agencies. As the Mission comes to a close, there is little clarity on who is responsible for the projects planned and executed by the SPVs. There is also little clarity on what happens to them after June 2024. If they continue, how will they be funded? Will they be absorbed into the corresponding ULBs? Who will oversee and fund the projects initiated under the Mission?

When the Mission was launched there was optimism that these SPVs would be financially independent. Largely speaking, this has not come to pass. In fact, the Mission budget of Rs 2 lakh crore and its spend of Rs 1,67,801 crore is barely one percent of the projected USD 1.2 trillion needed by 2020 to make Indian cities liveable, according to reports by McKinsey.

The lack of adequate alignment and coordination with the ULBs means these are unwilling to take on the smart city projects or do not have the capacity to do so. Sustaining the projects requires continued funding. Will the MOHUA or state governments continue funding of the projects or the SPVs? If yes, the SPVs become yet another agency for city planning and development in an already complex and fraught urban terrain while the ULB – the constitutionally empowered city government – continues to lose capacity, funds, and decision- making powers. On the other hand, without SPVs or continued funding, cities run the risk of losing the gains made under the Smart Cities Mission.

Critical questions

I have focused on two aspects in a complex and multi-faceted policy: digitalisation and governing structure. However, the Smart Cities Mission, by focussing on certain select areas of cities and on digitalisation became exclusionary at both physical and social levels. The area-based development excluded, from the Mission’s purview, large areas of cities where basic amenities were most badly needed which, often, meant an exclusion of a large number of people too.

Photo: Ehab Samy/ Flickr

This is inter-related to the crucial aspects of the focus on digitalisation and governing structure. The way the Mission was formulated and implemented pushes us to ask: is it possible for digitalisation to improve the governance of cities? If so, who should govern India’s cities: bureaucrats and consultants or elected representatives through accountable administrations? These questions have a direct bearing on the 74th Constitutional Amendment and its relevance in the age of the SPV-isation of urban governance.

However, if urban governance should lead digitalisation, then we have to re-focus attention on strengthening local governments. The ULBs must build their own capacity, elected city officials should lead decision-making, and citizens and civil society must be part of these decisions and transformations. This, I argue, is what the MOHUA should be investing in, moving forward.

The Smart Cities Mission was preceded by the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) with which it shares commonalities and continuities. The JNNURM encouraged the introduction of e-services in city government but it also focused on strengthening the ULBs and introduced a number of funding-linked requirements for it.

The MOHUA has moved on to launch the nation-wide National Urban Digital Mission in 2021. While digitalisation continues to be a priority, capacity-building of local governments does not seem to be, given that state governments have become important conduits for urban digitalisation. Empowering ULBs would have been the way forward even on the limited agenda of digitalisation.

Uttara Purandare recently completed her PhD in Public Policy, jointly awarded by IIT Bombay and Monash University. She is currently a Research Fellow at the Centre for Policy Studies, IIT Bombay.

Cover photo: Wikimedia Commons