As cities grapple with the growing impacts of climate change, the importance of vulnerability assessments and mapping has become increasingly evident. These tools are critical to identify risks and guide interventions that are needed to address the climate-related challenges. Cities have drawn up or are preparing climate action plans or more specific plans to deal with heat and floods. While these are essential, they may not be enough, as many of them often remain broad and technocratic, overlooking the everyday realities of the people most affected.

To create meaningful change, especially for the millions of marginalised people affected in cities across India, it is essential to move beyond surface-level analyses to embrace approaches that are rooted in the uniqueness of neighbourhoods and the myriad socio-spatial dynamics. The local spaces, the neighbourhoods, in our cities is where the action and the future are.

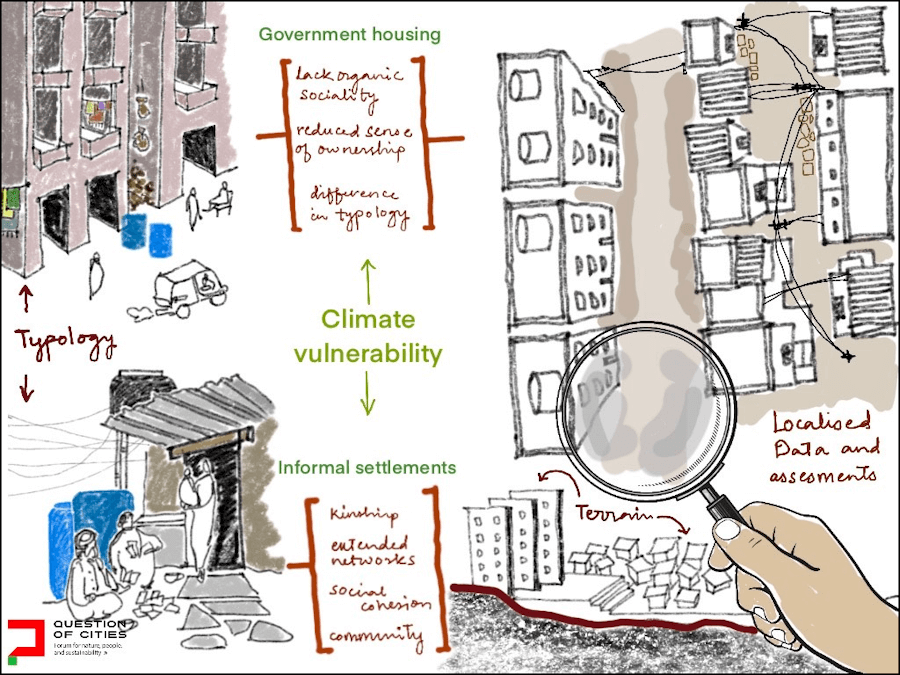

The distinctiveness of neighbourhoods and wards in the context of climate vulnerability is shaped by a multitude of factors including terrain, typology, social dynamics, politics, and historical and spatial contexts. Even within the same neighbourhood, there are factors of difference that subject certain people and dwellings to more climate risks than others within it. Similarly, two neighbourhoods or wards adjoining each other, while sharing administrative similarities and having porous boundaries, can have different social contexts, bringing up completely new problems and challenges.

In Hyderabad’s Singareni Colony, for instance, an informal settlement co-exists with government housing blocks, each facing different challenges. Understanding these intra-neighbourhood disparities is crucial for designing targeted climate resilience strategies. The work was carried out by Hyderabad Urban Lab (HUL), Indian Institute of Technology, Hyderabad, and Swastik Harish and Associates.

Located in Saidapet, Singareni Colony is partly an informal settlement that came to be in the early 2000s with leadership from the Communist Party of India. Poor, working class people from the city and migrants from surrounding districts working as daily wage labourers, domestic workers, construction workers and autorickshaw drivers, started settling into vacant land assigned to the Singareni Officers Housing Society’s land parcels. In 2005, due to a fire accident, a part of the informal settlement burnt down. To rehabilitate the affected people, the Congress government then announced the construction of housing units under the Valmiki Ambedkar Awas Yojana (VAMBAY). This led to the creation of two typologies within the neighbourhood: the informal settlement and the VAMBAY public housing blocks.

In the informal settlement, social cohesion took shape organically as families and extended networks moved together and settled close to one another. In contrast, the VAMBAY government housing blocks lack this sociality due to the randomised allocation of homes and the lack of built environment and common spaces necessary for social interaction, making it tougher to foster a sense of shared ownership and connection with the surroundings, leaving public spaces to fall into neglect.

These differences highlight the importance of recognising that climate vulnerability is not a one-size-fits-all issue and involves many socio-spatial layers. While both sections of Singareni Colony experience urban heat stress, their ability to cope with and respond to these challenges differs. Residents of the informal settlement, despite living in precarious housing conditions without tenure or access to water connections, rely on social networks and communal spaces to access resources. Those in the government blocks, with less social cohesion and no community spaces, often struggle with a sense of isolation and neglect.

While neither group is inherently more or less vulnerable, these differences shape their respective capacities to respond to climate risks and determine the kinds of interventions needed. This necessitates vulnerability assessments which capture such dynamic social conditions. This means assessments need to be conducted at the local level — neighbourhood or ward level. While there is increasing recognition of how vulnerability creates differential risks and vulnerable groups, the complexities of social conditions are dynamic and rarely fixed.

Climate risks entangled with social realities

Understanding climate vulnerability requires asking the right questions. Separating climate risks from everyday social realities distorts how governments, NGOs and climate finance organisations understand risk, often leading to ineffective or disconnected action plans. For instance, asking how people “adapt” to climate change ignores the on-ground reality that people are not merely adapting to climate change but are simultaneously adapting to long-standing social realities like insecure housing tenure, caste-based discrimination, and economic instability, which are intensified by climate risks. It follows then that challenges such as housing tenure, gendered violence, caste inequalities, and other social issues must be considered when addressing phenomena like heat stress or urban flooding.

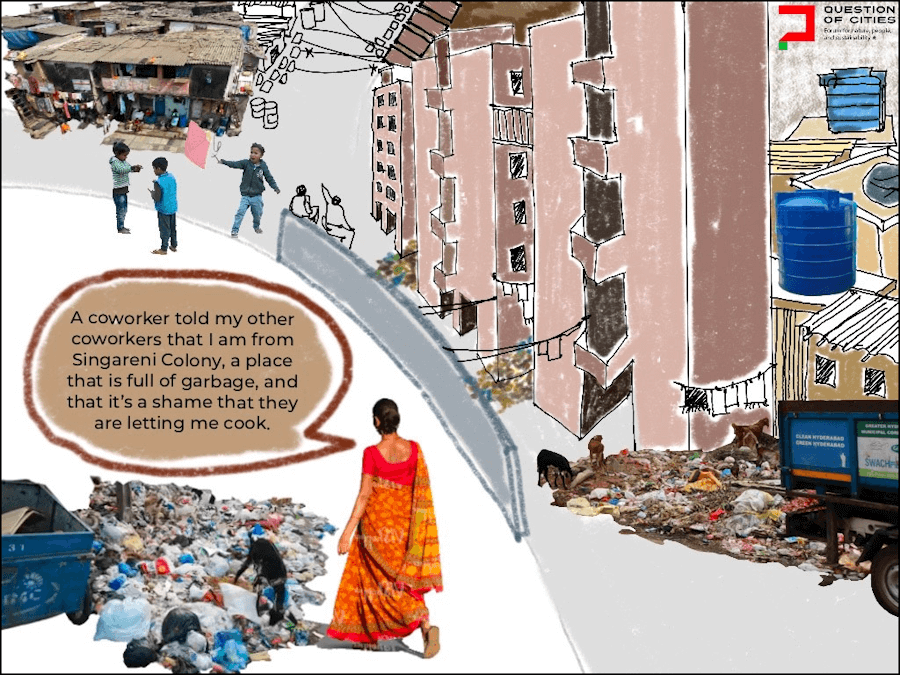

In Singareni Colony, when discussing heat or a discrete climate stressor, the conversation rarely stays focused on it. Other stressors quickly take over the discussion. Residents of the public housing colony often speak about the garbage-choked streets and back-lanes of their buildings as issues of dignity, self-respect, and ownership of their surroundings.

A woman resident, who works as a cook at a catering service, shared, “At work, a co-worker told my other co-workers that I am from Singareni Colony, a place that is full of garbage, and that it’s a shame that they are letting me cook. I’m scared I will lose the job. This makes me want to solve the menace of garbage.” There are other incidents like this which result in many residents aspiring to leave the colony for places that are maintained better, despite the higher living costs.

Similarly, a resident from the informal settlement who has lived here for more than 20 years lamented the precarious nature of housing – for fear of eviction – which prevents residents from upgrading their homes or accessing basic resources such as tap water supply, which is obtained through various strategies and negotiations including tanker supply and borewells the communities got built over the years. Without this security, residents remain in vulnerable housing conditions in kutcha or semi-pucca dwellings, unable to invest in heat-resilient structures or upgrade to pucca houses. One resident lamented: “Why would I invest in making my home stronger when I don’t even know if I can stay here tomorrow?”

This makes urban heat a triviality —something to be simply tolerated for a part of the year. Like a resident in Singareni Colony said, “What’s the need for doing anything about the heat? We just have to grit our teeth and tolerate it for the three months of April, May and a couple of weeks of June. I don’t want to make investments for something like an air cooler that will serve us for three months only and will be untouched for the rest of the year, taking up space. We have tolerated the summer heat year after year, it’s not new for us. We’ll do the same now.”

Such responses are fairly common in the locality here and residents see climate-related events such as high heat or floods as something “temporary” or as a matter of life itself. That it is a “temporary” event to deal with also leads to de-prioritisation in comparison to other long-standing issues like caste, dignity, tenure security and basic access to resources. For some, the aspiration to get out is far more important than the willingness to improve the conditions in Singareni Colony itself. This interplay of risks highlights why climate adaptation strategies must account for the competing demands on people’s time, energy, and resources.

Prioritising heat requires a nuanced understanding of how it intersects with—and is sometimes deprioritised by—other fundamental struggles. Without this, mitigation efforts risk being out of step with the lived realities of those most affected.

Why a participatory approach is a must

A meaningful participatory approach is important in understanding climate risks and vulnerability and planning for action. However, the term ‘participation’ often carries a superficial or tokenistic connotation in many participatory practices. Urban practice must move beyond mere consultations — commonly referred to as “hearing people’s voices”—towards co-production of knowledge, where communities are not only consulted but actively involved in shaping outcomes.

This approach requires building relationships, fostering solidarity, and cultivating genuine connections with community members. It also demands a willingness to stand with communities through challenges, ensuring that the process of vulnerability mapping does not become extractive or stay formulaic.

For instance, Singareni Colony is a frequent focal point for researchers, NGOs, and students, drawing a lot of academic and organisational attention, including for studies and organisational project work. Researchers, NGOs, and students frequently visit it for fieldwork. However, this often leads to feelings of betrayal, burnout, and mistrust within the community, as these engagements typically begin and end with data collection and data validation.

As Leela, a 40-something year old resident in the informal settlement says, “Actors and politicians drop by when something spectacularly bad happens, but they do nothing, just give us empty smiles. Three years ago, when a man raped a child and killed her, actor Chiranjeevi paid us a visit. But he did nothing. We’re tired of this exercise (research studies) too. People come here for their research projects, ask us some questions, and leave. Our lives stay the same.”

Involving communities in research and transformative action, by contrast, means fostering shared solidarity and a willingness to remain entangled in their struggles as organisations, urban practitioners, and researchers. Hyderabad Urban Lab Foundation (HUL), an interdisciplinary research and action initiative based in Hyderabad, is grounded in these principles. HUL recognises that the strength of community action lies in the relationships and solidarities built with, and within, the community. Anant Maringanti, executive director of HUL, reflects on the organisation’s approach to work in Bholakpur—a sub-locality in Hyderabad known for its bustling scrap markets. He emphasised that HUL not only assured the community of its commitment to stand with them in their struggles but also followed through by remaining engaged with the locality through all outcomes of their collaboration—good or bad.

As a result of HUL’s work in Singareni Colony, Kishanbagh, Bholakpur, and other areas of Hyderabad, lasting friendships have been built with organisations like Dalit Women’s Collective, local residents involved in social and entrepreneurial work, community leaders, and civil society members. These relationships inform HUL’s approach https://hydlab.co.in while simultaneously being shaped by HUL, fostering a shared and collaborative space. At HUL, relationships extend beyond the organisation. Former members carry their connections and experiences into new spaces, while newcomers cultivate their own ties within the community and civil society members, through existing bi-directional pathways. This ongoing exchange fosters a collaborative and evolving network, shaping both individuals and the shared work they engage in.

Solidarity can generate crucial and transformative knowledge. As social inequalities, the built environment, and climate risks intersect, solidarity fosters insights grounded in lived experiences, collective struggles, and a deeper systemic understanding. This kind of knowledge serves as a valuable complement to formulaic vulnerability mapping, which can sometimes risk oversimplifying complex realities.

In Singareni Colony, such an approach fostered awareness of how heat stress intersects with aspirations, job security, dignity, and access to resources, highlighting the systemic nature of these risks. In one of its collaborative research studies in the locality, HUL took up a placemaking initiative in Singareni Colony, clearing up a potential community space riddled with piles of garbage. Engaging with the community beyond the confines of one study was a way to cue into its struggles from different perspectives and contexts.

Such localised approaches ensure that vulnerability mapping and adaptation strategies are not just theoretical but are grounded in the lived experiences of the communities that need them the most. Ultimately, vulnerability mapping should not just be a tool for identifying risks—it should be a pathway towards building resilience and fostering justice for the most affected communities.

It is also critical to consider how solidarity and friendships can shape and inform action and how organisations and urban practitioners can build and foster these connections.

Hence, centralised, top-down mitigation strategies or climate action plans are not enough to address the complex and multi-layered risks experienced by residents. Instead, efforts by NGOs, urban practitioners, and governments must focus on enabling communities to understand their local risks, identify their strengths, and advocate for hyperlocal action tailored to their specific contexts.

This essay builds on insights from work done under the Cool Infrastructures project and the research and fieldwork I undertook together with my colleagues, Andrew deSouza, Chidananda Arpita, Phanisri Chavali, Tanaya Bhowal, and Rittu Anilkumar. I am grateful to Dr. Anant Maringanti for shaping my understanding of the site and the city and guiding my approach to this work.

Meghana Myadam is an urban researcher at Hyderabad Urban Lab, an action and research institute. They study social and spatial dynamics of risk in urban contexts. Their work explores urban heat, urban flooding, placemaking, and risk pedagogy. They hold an M.A. in Development Studies from the Tata Institute of Social Sciences.

Illustrations: Nikeita Saraf