The Yamuna River, flowing through Delhi, is infamous for its pollution. It carries the city’s untreated waste and industrial effluents, and its banks have waste dumps too. This month’s report of the Delhi Pollution Control Committee showed an alarming decline in the river’s quality compared to June. At the ITO Bridge, faecal coliform levels 4,000 times over the permissible limit were recorded last month. The river’s Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD), or the amount of oxygen to break down organic matter, at Pall is almost three times (8mg/l) Central Pollution Contril Board’s safe limit.[1]

The river, which flooded the city most recently in 2023, may well flood the city again because hardly any substantive action has been taken. The recently launched 45-point action plan to clean it is among the many initiatives since 1993 when the Yamuna Action Plan was launched. “The fragmented approach to clean the river has limited itself to pollution issues and has conveniently overlooked factors impacting overall health of the river,” says environment activist Bhim Singh Rawat, also an associate coordinator of the South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People (SANDRP). He reminds us that since Delhi sits on the Yamuna river basin, every action negatively impacts the river.

How has Delhi’s relationship with the Yamuna changed over the years?

When Delhi was less populated, there were temporary villages along the river. People moved to higher places when it flooded. They farmed along the river and grazed cattle. Later, canals were built to divert water from the river. After the Partition, refugees came to Delhi in large numbers and built settlements in Yamuna Park and along the Najafgarh drain. Since then, people felt the need to structure the river. The government wanted to protect people and their homes from floods, so the land use of floodplains began to be changed. Even after the drainage system, the river’s flow and aquatic and ecological health were okay. The problem started when Delhi’s population increased.

What specifically caused the deterioration of the river?

The aesthetic focus on the river began after the Yamuna Action Plan was introduced. Both the government and people’s actions began impacting the river as industrial demands increased and agriculture developed. People’s religious and recreational dependence on the river continued. The overall impact was not seen for years but the flow of the river reduced and pollution increased. People continue to depend on it, bathe in it even today. If the river has such religious significance and is a source of livelihood, why was no one ready for its deterioration?

The government banned fishing but encroached the floodplains and displaced settlers to build concrete structures, dams, temples, and metro depots. They privatised it all, so to see the river, one has to pay. They went further to build eateries, advertising for picnics and events. In this set-up, people do not have a strong relationship with the river. They are not vocal, do not demand anything from the government. The government also finds easy ways out. So, there’s a fracturing of people’s bond with the river.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

What problems does the river face?

The founding basin is very sensitive and small, there are limited water sources. We are ignoring this and constantly doing higher water extraction though a Parliamentary Committee Report said that the river needs 23 cubic metres of flow.[2] Secondly, the river flows through a hilly region and as it enters the plains, water is diverted naturally. Then, there’s unsustainable industrialisation and mining.

After the landmark judgment in 2012 of Manoj Misra, the well-known environmentalist, versus Union of India[3] there were mining regulations but the situation has worsened since then. The groundwater levels have decreased. The extraction of sand and water means the river’s flow is hindered and its system hijacked. Mining work stops during the monsoon but it is aggressively done till May, violating all norms and changing the river’s course. Mining is not allowed at night but it goes on 24/7. There’s no monitoring.

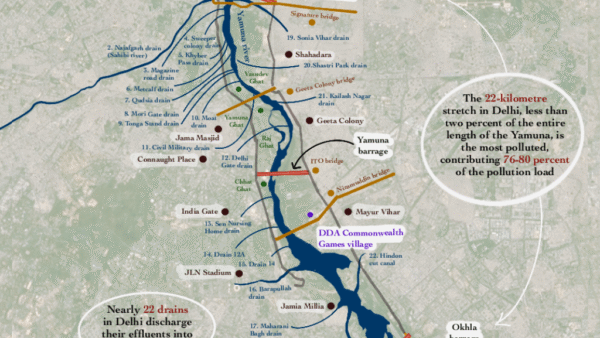

There are three barrages, including the ITO barrage and Okhla barrage, in a 22-kilometre stretch and more than 25 bridges with another three-four under construction. All this has fragmented the floodplains and channelised the river. In the monsoon, the river cannot meander freely. Researchers, student groups, think tanks, and the government are focused on cleaning the river without addressing these issues. Government reports show that if the sewage treatment plants in Delhi worked at optimum capacity and the river was allowed to flow, the desired water quality could be maintained.

How can the river get its space?

Manoj Misra told me that the river is quite a unique system. During the monsoon, the river flushes out the fields, occupies the floodplains, and allows the migration of fish. The native vegetation gets rejuvenated. The Yamuna is not able to do that. Instead, at Vasudev Ghat, artificial grass is being watered with ground water. There is no biodiversity, only ornamental plants. On the riverbank, the government has planted bamboo trees and laid a carpet of red coarse sand called baloo on it.

The flood removed all this and, thankfully, the native vegetation came back. I was able to see dragon flies, butterflies, insects and spiders. If you let a river flow, it will repair itself. The industrial effluents have to be stopped and sewage treated. Delhi performs poorly at rainwater harvesting too. All this, if done right, can reduce the pollution in the river. The Yamuna cleans itself every monsoon but things go back to square one after these two months. Reviving the river ecology requires dedicated efforts.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

How far has the government action for Yamuna’s revival progressed?

The Delhi government has plans to clean the river but other departments have projects to exploit it. The Central Water Commission is proposing dams which will disrupt its flow. So, on the one hand, the authorities are investing in infrastructure that will stop the river from flowing while, on the other hand, they want to clean the river. This is a fundamental problem in the approach. Governments also have vested interests. They want to carry out riverfront development which means to grab land from the floodplains that become real estate after beautification, and people think that something phenomenal has happened.

The floods in July 2023 affected all the projects that the Delhi Development Authority was working on for the last four-five years and it suffered a loss of Rs 40.6 crore. But there is no accountability.[4] It was public money. There is a dearth of advocacy from civil society unlike in Pune where citizens are protesting to save the Mula-Mutha. The courts, particularly the National Green Tribunal, take cognisance of some issues, set up committees, issue notices and then forget about it. But they come down strongly on the floodplains farmers and fisherfolk. We had independent monitoring committees but this does not happen anymore. In 1978, 7 lakh cusec water was released and it was a benchmark flood. In July 2023, it was 3.50 lakh cusec – half the discharge – but it still breached the boundary. Delhi has not learnt any lessons, done nothing to course correct.

How can the river’s carrying capacity be increased?

The flooding of a river is a natural phenomenon, it keeps the river system alive. We have made flooding a damaging phenomenon by taking over the riverbed. The flood of 1978 stretched till GT Karnal Road but now there are embankments. The floodplains have been restricted and we want to further build inside what’s left of it. This is bound to cause damage. A hospital has been constructed on the western floodbank at Kashmiri Gate, citing public health needs.

We need to save what is left of the Yamuna floodplains in Delhi from mostly government-sponsored encroachment. It will be great if they start undoing the encroachments like metro depots, IT parks and bridges. I doubt they can reverse the Commonwealth Games village where the basements of structures flood. There are several road projects like the Outer Ring Road planned along the river. Delhi is creating more problems for itself. There is a River Regulation Zone Bill pending in the Parliament which needs public consultation and notification.

How can the people-river connection be rekindled?

Delhi sits on the Yamuna river basin and every action impacts the river negatively. Groundwater is being extracted, solid waste is released, unsegregated waste is dumped everywhere, trees are not protected, waterbodies are degrading. Whatever steps taken to address these will help restore the river. When I saw the river in 2009, I realised I was a part of the problem and I had to be a part of the solution. There is a vacuum in civil society groups that advocate for rivers in Delhi after the passing of Manoj Misra. If more people get together, we can at least curb the mindless construction on the floodplains. The well-to-do people need to take the lead on this, awareness needs to become action.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

What are your prescriptions to restore the river?

Restoring the Yamuna is a complex process. It will require consistent interventions at multiple levels by all basin states with key central agencies in the steering position. It’s important to restore the feeding streams, the tributaries in the Yamuna catchment along its course, by protecting forests and local water bodies, initiating rainwater harvesting, stopping unsustainable mining, preventing encroachments on floodplains and removing existing encroachments, and judicious use of water in the river basin. The government is the biggest landlord, it can set an example through all its lands and buildings.

We also need to restore longitudinal, lateral and vertical connectivities of the Yamuna and its tributaries at all locations of dams and barrages, and stop building river- destroying structures. In the upper segment, Delhi, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh have overstressed the river ecosystem. They need urgent and serious policy interventions, and an urban water policy too. In fact, we need a National Urban Water Policy, state-level similar policy, and National River Policy. We also need smart water city programmes, not just smart city programmes. These measures can help. This is equally true for districts and urban areas in the Yamuna basin in Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and UP constituting the middle and lower segments of the river.

Who should do what towards this?

At the heart of the continual deterioration of Yamuna is the sheer absence of river governance mechanism in India and the Yamuna basin in particular. There is no governance that will ensure functioning of the Sewage Treatment Plants (STP) and Common Effluent Treatment Plants (CETPs) qualitatively and quantitatively as per design, and ensure transparent accountability norms so that there are consequences in case of non-functioning.

The fragmented approach to clean the river has limited itself to pollution and conveniently overlooked factors impacting the overall health of the river. As a result, there is hardly any achievement on this front. The formation of a statutory and autonomous body such as Yamuna Rivers Protection and Conservation Board, and central and state level holistic plans and interventions can be a start. It must have independent domain experts as members and representatives of multiple government agencies from Yamuna basin states. Then, setting up of bottom-up River Basin Organisations of concerned people, community groups, independent experts, urban local bodies, Resident Welfare Associations (RWAs), water users’ associations is also required to ensure efficiency, transparency and accountability. The river will repair itself if we let it be.

Cover photo: Wikimedia Commons