“In rehabilitating these forgotten pioneers, I do not wish to suggest that in their work one can find specific solutions to all the environmental problems of the present. While it was Patrick Geddes who coined the memorable phrase ‘carboniferous capitalism’, these individuals all mostly wrote before the arrival of the age of private motorised transport…these environmentalists who lived well before climate change became visible are nonetheless worthy of attention and respect in an age so dominated by it. They worked in many socio-ecological domains: the wild, the forest, the farm, the village, the city. They came from different disciplinary and intellectual backgrounds. Their heterogeneous legacies refute simple-minded dichotomies that posit modernity versus tradition, science versus activism, East versus West, nature versus humanity.”

These are among the last words of the epilogue that Ramachandra Guha, historian and celebrated author, has in his latest book Speaking with Nature – The Origins of Indian Environmentalism published late 2024. In tracing the environmental work of ten people in history, some known and others less so, Guha says he has offered “a compost of environmentalism and environmentalists” that may organically fertilise minds to see the Indian ethos of environmentalism, the ideas and approaches then, and allow it to inform the ideas and actions today. The book is part profile, part history, and part intellectual anchor of environmentalism in India.

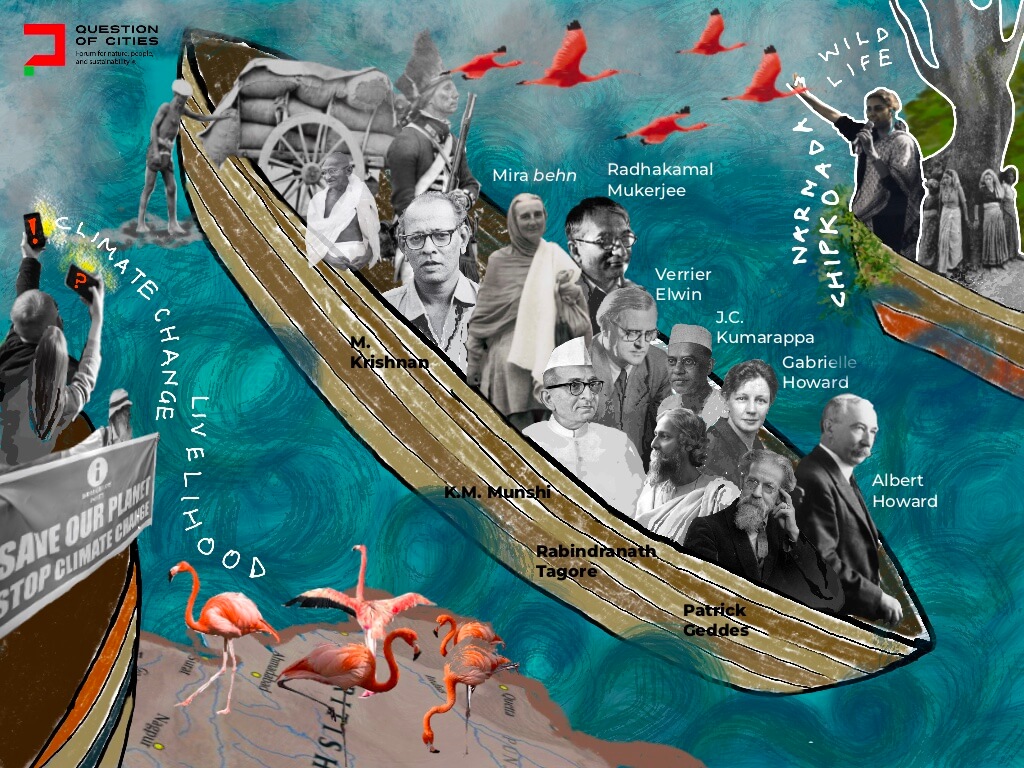

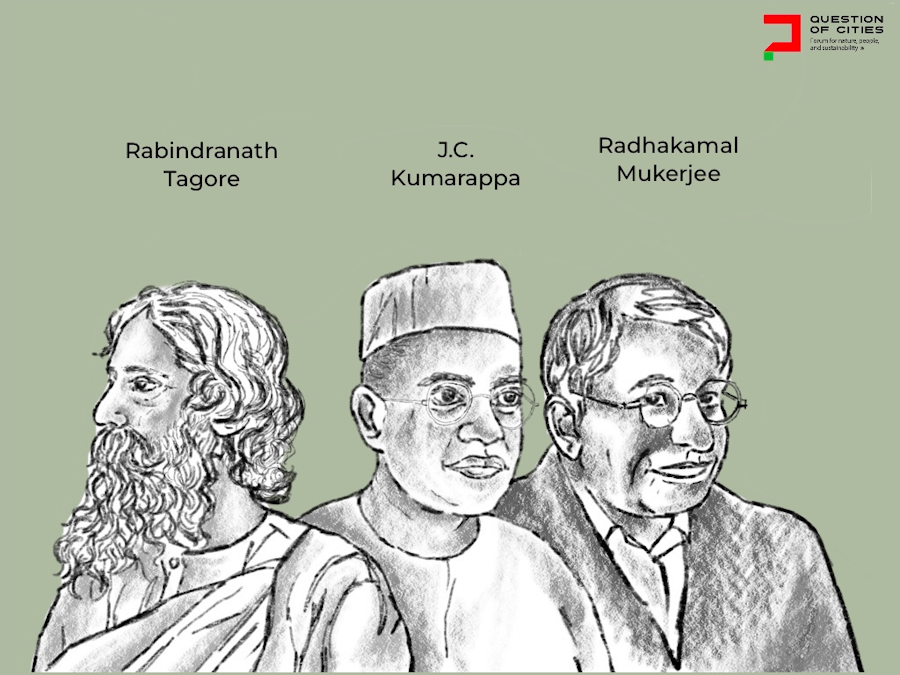

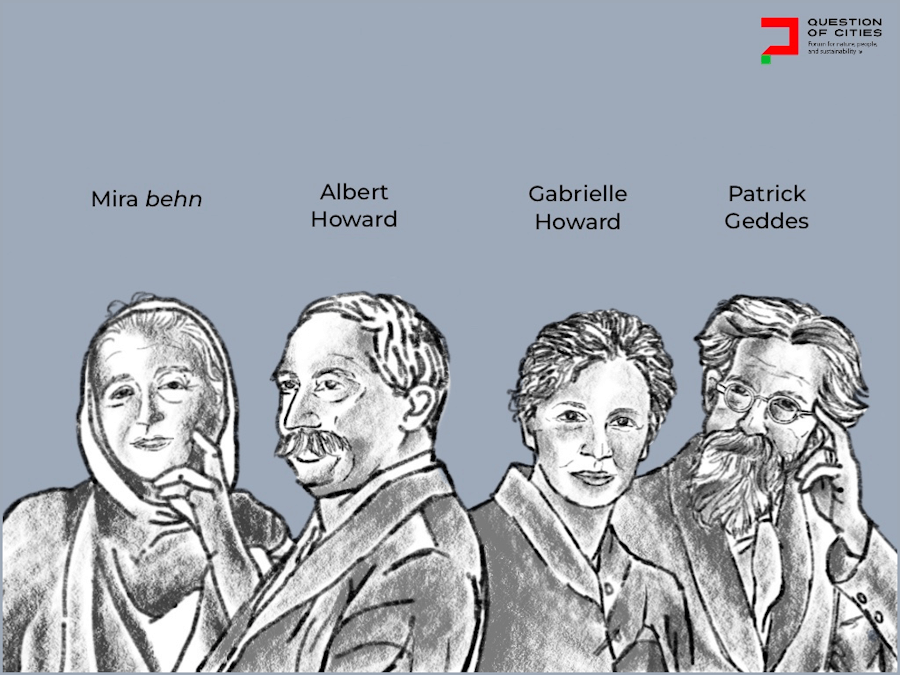

Guha’s set of ten is an eclectic one. He returns to Mahatma Gandhi, on whom he has extensively written, but not to the man himself; instead, he profiles the life and environmental work of Gandhi-inspired people like JC Kumarappa and Mira. Then, he acquaints us with the environmental ideas and writing of Rabindranath Tagore whom he calls “unacknowledged founder of the modern Indian environmental movement”, ecological sociologist Radhakamal Mukerjee, Scottish town planner and sociologist-biologist Patrick Geddes, scientist couple Albert and Gabrielle Howard, anthropologist Verrier Elwin, KM Munshi who was the “first Hindutva environmentalist”, and naturalist M Krishnan.

The purpose here is not to merely self-indulge but to place on record a narrative, a thread, of Indian environmentalism – distinct from American or European environmentalisms – through the ideas and writings of the ten who, individually and collectively “speak to the environmental concerns of our own time”. The value of Guha’s work lies not only in getting acquainted with the ten personalities but what their environmental thoughts and work means for us today. Guha is careful to state that the book “is an exercise in reconstruction, not prescription” but this book is an important read for environmentalists, the media, and academia.

He has dug in deep, unearthed environmentalism of people we did not see as environmentalists (Mira and Munshi, to cite two), and connected them to social issues and movements of their time. We read them all, rooted in the Indian ethos, through direct quotations from their writing or speeches, see them grappling with environmental concerns besides their core political or social interests, get a sense of the times they lived in – and draw inferences (or not) for the present. Guha’s title for the epilogue A Partially Usable Past says it all. The work of sifting ideas and taking lessons from them for today’s battles, the fundamental of which is against climate change, is ours; Guha’s rendering offers ideas and paths. This is the first strength of the book.

The second is that the book maps the three waves of environmentalism in India, as he puts it, and resolutely focuses on the first and significant one. This “forgotten first wave of environmentalism” in India, he shows, is not only distinct but predates environmentalism in other parts of the world, yet has received little to no recognition by environmental historians or, even, historians. In doing so, the book provides contemporary Indian environmentalism with “a credible intellectual genealogy” which Guha wanted to do back in the 1990s.

He had first expressed this idea in a scholarly article in 1992 which focused on four of the ten featured in this book – Kumarappa, Mukerjee, Geddes, and Elwin. That work, he had hoped, would do for India what American environmental historians had done for theirs. Guha later elaborated this in Varieties of Environmentalism: Essays North and South which he co-authored with Joan Martinez-Alier, Catalan economist whose contribution to ecological economics, political ecology, and environmentalism of the poor is legendary.

Speaking with Nature, dedicated to Martinez-Alier, continues on that path, of course, with more personalities strengthening the original argument. Those he wrote about earlier are presented with more details and sharp confidence. Could the core arguments about Indian environmentalism have been teased out further, more angles explored? Perhaps, yes. Nevertheless, with the advantage that Guha’s star-author status now lends it, it should persuade the world to see the depth of environmental history.

This first wave of environmentalism in India was followed by the second in the 1980s when, Guha writes, “environmental history was in its infancy” and Indian activists – “monumentally ahistorical” he terms them – were busy reshaping the present for a sustainable future. “Though they nodded respectfully to Chipko as marking the beginning of their movements, they looked no further back,” he writes. Guha stresses that India’s environmentalism did not start with the Chipko movement, however legendary it is. The third wave is the one “provoked and stimulated by the challenge of climate change” and the book’s audience are those who are aware of and participate in it.

The third strength of the book is that while its focus is on the environmental aspect of the chosen ten, it profiles each one in detail and places them in a historical context. Some names as ‘environmentalists’ may surprise such as Rabindranath Tagore but Guha shows he advocated and created classrooms in nature, open to the sky and surrounded by the trees and birds. He may also have been “one of the first writers to recognise the damaging ecological—as distinct from political or economic—effects of Western imperialism”. Mira (or Madeleine) is another example. Known for her work as a Gandhian and devotion to Gandhi, she had not been profiled as an environmentalist – till now. She and Gabrielle Howard are the only two women here but Guha acknowledges it.

Similarly, lawyer, Gujarati novelist, and Congressman KM Munshi finds mention. His environmental concerns were clothed in Hindu imagery and mythological references. Munshi, minister for food and agriculture in Jawaharlal Nehru’s cabinet, was given charge of the forest department which then was about one-fifth of India’s territory. In the week-long Vana Mahotsav (festival of forest) that he rolled out as part of forest conservation, Munshi advocated that everyone in India turn vegetarian for the week.

For those unfamiliar with the work of Elwin, Geddes and Howard, the profiles hold attention. Krishnan is less-known of them all, a trained botanist and lawyer based in Madras who put nature above all else, travelled across India and wrote extensively in The Illustrated Weekly and The Statesman, and was instrumental in the setting up sanctuaries.

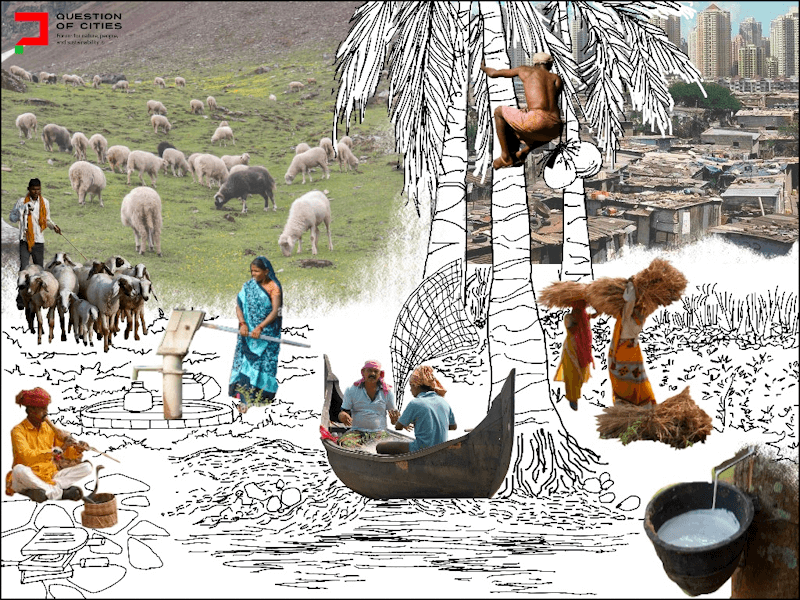

Except Krishnan, others approached nature from the human perspective, in a pragmatic way. Some like Mira understood the intricate connection between nature, agriculture, and people’s welfare, and, Guha notes, wrote in private to Nehru about her disenchantment with the political-economic path free India was following (of rapid industrialisation and mechanisation). Economist Mukerjee, was a votary of common property resources and, Guha shows, was of the opinion that the vigorous community control of forests, pasture and water had decayed and atrophied under British colonial rule.

The subtext in nearly every profile is political, the context in which the ten give words to their environmentalism is political, the approach that some of them choose is also political. It is only natural given the intense political, even radical, times they lived and wrote in. Yet, the book refrains from exploring and intellectualising the politics of their environmentalism. This cuts both ways. Overt political inferences might have taken away from the focus on their environmentalism and, it can be argued, that this task is best left to readers.

However, the environmental question in any era is necessarily and inescapably a political question. A political interpretation and evaluation of the environmentalism of the ten, in the colonial-capitalist context, would have helped deepen the understanding of India’s environmentalism. But, above all, Speaking with Nature is a social scientist and storyteller’s narrative of India’s environmental past through ten personalities and, importantly, an assertion that ideas matter as much as the material work of environmentalism on the ground. It’s a book to keep – and return to for inspiration.

Selected lines from the ten pioneers

Rabindranath Tagore:

“The political civilisation which has sprung up from the soil of England (and) is overrunning the whole world, like some prolific weed, is based on exclusiveness…It is carnivorous and cannibalistic in its tendencies, it feeds upon the resources of other peoples and tries to swallow their whole future.” (1916)

“Take a man from his natural surroundings, from the fullness of his communal life, with all its living associations of beauty and love and social obligations, and you will be able to turn him into so many fragments of a machine for the production of wealth on a gigantic scale. Turn a tree into a log and it will burn for you, but it will never bear living flowers and fruits.” (1917)

Radhakamal Mukerjee

“Human, animal and plant communities are subject to similar rules, though shifting ones, which maintain a balance and rhythm of growth for all. Each community cannot appropriate more than its due place in the general ordering of life…Working symbiotically, they represent inter-woven threads of a complex web of life. No one thread can be isolated. None can be snapped or removed without the whole garment of the life of nature and human society being disfigured… Though man often tears asunder the fabric through ignorance or selfishness, social progress no doubt consists in consciously weaving the forces of nature and society into finer and finer patterns of correlation and solidarity.” (1930)

JC Kumarappa

“It is not possible in this short note to give examples of the extravagant ways of the Americans which they have followed in the past in building up their country; how they have burnt forests and built roads and wasted their lands with short-term agricultural methods…It’s impossible for us to use such persons as our guides and yet hope to succeed…The sooner India turns to her own genius and relies on her own strength and resources for development, the better it will be for herself and her message of peace to the world.

Patrick Geddes

“…the case for conservation of nature and for the increase of our accesses to her…that ‘return to nature’ which every adequate plan involves, , with pure air and water, and cleanliness in surroundings again rural…the problem is how to accomplish this return to the health of village life with its beauty of surroundings and its contact with nature, upon a new spiral turning beyond the old one which, at the same time, frankly and fully incorporates the best advantages of town-life.”

Albert and Gabrielle Howard

“The remedy is to look at the whole field covered by crop production, animal husbandry, food, nutrition, and health as one related subject and then to realise the great principle that the birthright of every crop, every animal, and every human being is health.”

Mira

“The tragedy today is that educated and moneyed classes are altogether out of touch with the vital fundamentals of existence – our Mother Earth, and the animal and vegetable population which she sustains. This world of Nature’s planning is ruthlessly plundered, despoiled and disorganised by man whenever he gets the chance. By his science and machinery, he may get huge returns for a time, but ultimately will come desolation. We have got to study Nature’s balance, and develop our lives within her laws, if we are to survive as a physically healthy and morally decent species.” (1949)

“Everything had been going on merrily, and we were being told that a wonderful new world was opening up. But the wonderful new world is proving to be a death-trap. Day after day we read in the newspapers of the deadly tide of pollution which is overtaking us –on all sides poison and ever-increasing piles of waste; waste which represents reckless destruction of the Earth’s natural resources.” (1974)

Verrier Elwin

“I have myself recorded the melancholy story of the effect of reservation on the Baigas of Madhya Pradesh in my book on the tribe. Nothing roused the Saoras of Orissa to such resentment as the taking from them of forests which they regarded as their own property. Of the Bhuiyas and Juangs of Bonai and Keonjhar, I wrote in a report in 1942: It is necessary for us to appreciate the attitude of the aboriginal. To him the hills and forests are his. Again and again it was said to me, ‘these hills are ours; what right has anyone to interfere in our own property?’” (1957)

KM Munshi

“Everyone from the humble shepherd to the President of the Republic, has to be tree-conscious. It should be accepted as a religious duty for every one to plant a tree, to water it, to preserve it, to protect it. To us Indians, it should come naturally, for the tree is sacred to us; it is associated with Vedic hymns, with the bel tree sacred to Shiva, with Shri Krishna’s whole life, with the divine tulsi (plant) in every home, with the pipal (tree) which, as Bhagavad-Gita says, is God Himself.” (1951)

M Krishnan

“I have seen forested hills denuded, and reduced to bare, boulder-strewn slopes, within a period of four years. And over the past forty years I have observed the shady revenue and large, tree-grown compounds, the palm groves and green fields, and the mud-flats in and around Madras City gradually turn into congested housing colonies, and watched their rich bird life get impoverished. All over India, such things have been happening with increasing frequency and tempo…We must know how and why there has been this devastation of our great heritage of nature, to save what is left.” (1965)