Taxi driver Mohammad Javed, 56, a resident of Kurla in Mumbai, was in between jobs when the city flooded like never before in memory on July 26, 2005. He had gone to fetch his sister’s twin children from school in the heavy downpour. “I carried one on my shoulders and held the other on my arm as I trudged home in waist-deep water. I saw the water rising. Soon, cars and auto rickshaws were swept away,” he recalls.

Kurla, an eastern suburb of the city, was among the worst affected areas. A mixed area, it housed thousands of small-scale commercial establishments and middle-to-low income homes. As Javed watched in horror from his house, the situation worsened. “In a few hours, I saw a corpse float by. Some young men placed it on top of a submerged rickshaw. It was bloated the next day. What a harrowing sight,” he shudders. A pump has since been installed in his locality which throws out rainwater. “This monsoon has been kinder,” he says.

Almost two decades after the devastating deluge brought Mumbai to a standstill, torrential and continuous rain still causes widespread worry, anxiety and despair. This shows in the concerned voice of a cab driver who dropped me on a day that the skies had opened up and parts of Mumbai recorded around 300 millimetres rain: “Beta, aaj chaar baje tak ghar pohoch jaana (Child, reach home by 4 pm today.)”

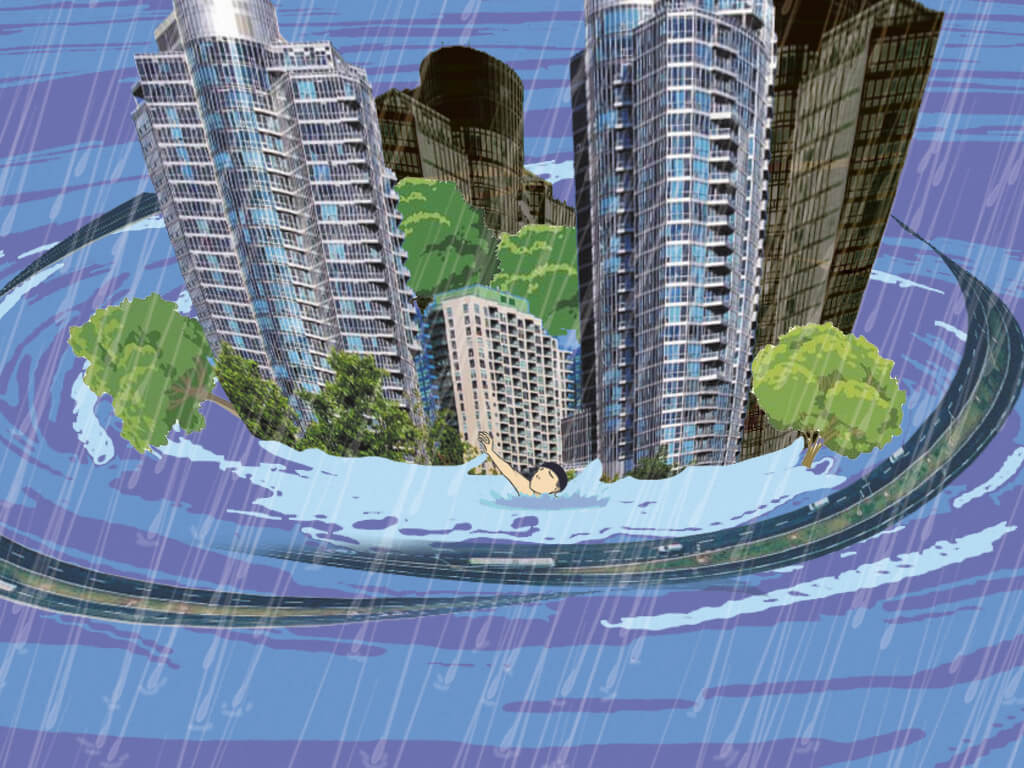

Memories of that fateful July day are firmly imprinted on the minds of Mumbaikars. The rising waters flooded houses and turned roads into rivers, stranded people made human chains and waded in the waist-deep water. The utter mayhem and chaos derailed all means of transport. At least 1,100 were killed and many lakhs stranded.

Forty-two-year-old Sandeep, who lived in the northern suburb of Kandivli, was lucky to have escaped the chaos. “I lived on a higher floor so water did not enter my home. My neighbours were frantic as water entered their ground floor homes. I helped many living on lower floors relocate to upper floors – they lost belongings and important papers.” He recalled having teamed up with others to offer kande pohe (Maharashtrian rice flakes snack) to those who had waded through waist-deep water for hours to reach home.

The low-lying suburban areas such as Kalina (where the Mithi River was bent for the airport), Malad, Chembur, Kurla, Andheri, Dharavi, Govandi and Bandra-Kurla Complex saw the highest flood levels that day when Mumbai received 944 mm of rain in just 24 hours.[1]

Mumbai suffered far more than its financial losses, which were pegged at around Rs 5.5 billion.[2] Besides the 1,100 people recorded dead, many in the city’s informal settlements remained untraceable. People stranded in cars on flooded roads had died inside. More than 2,53,600 metric tonnes of debris and garbage was collected over the next few days, as per the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) records.

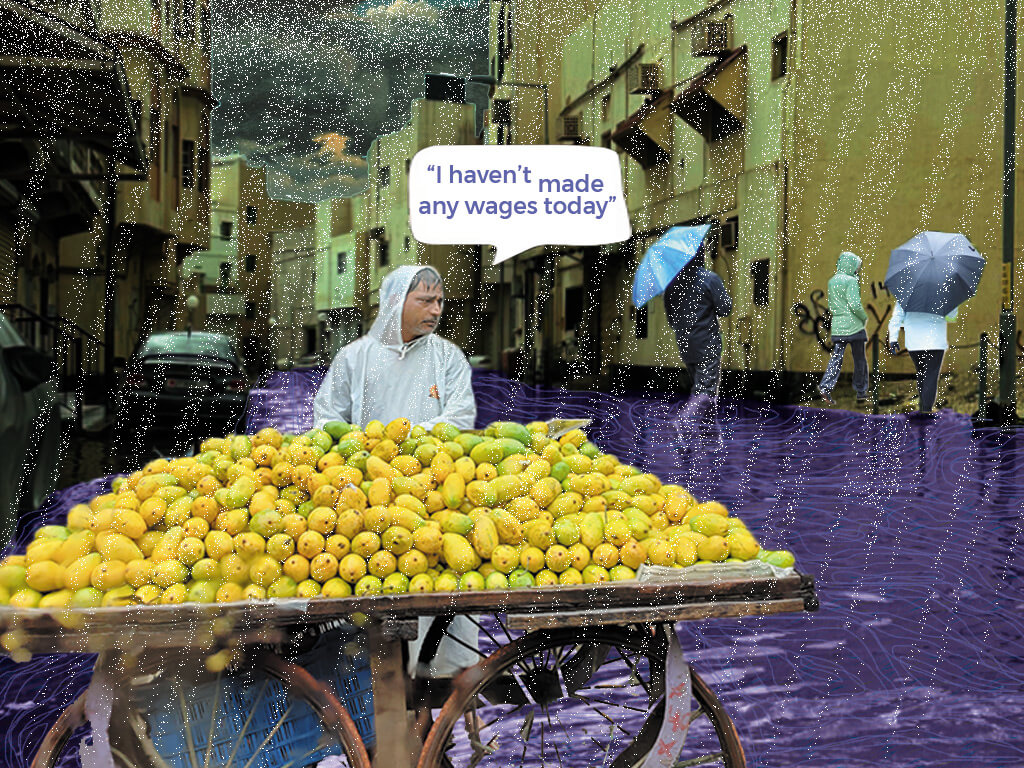

Even today, if the city sees 55 millimetres (2.1 inches) of rain over an hour while simultaneously experiencing a high tide, the low-lying areas start flooding. The BMC has since installed pumps to help clear these areas.[3] Over the years, the rainfall intensity has increased with the city recording well over the 55-millimetre mark in July-August. Waterlogging has become common every monsoon, exposing the lack of a city-wide flood management and resilience plan. Measures such as installing local pumps for flood mitigation do not help but officials hope that they give people the confidence that something is working. Vendors, informal workers and daily wage workers still venture out in the heavy downpour, not wanting to lose a day’s earnings.

Informal workers like 59-year-old Ramesh Nivrut Sonavne cannot afford to take a day off work either. Fondly known as chattri che doctor (umbrella doctor), Sonavne has spent the past 50 years at the Sion Circle, making and selling umbrellas, fixing shoes and belts, and becoming a routine hang for many who stroll by the area. He works in a makeshift stall open to the elements.

“I have never missed a day of work; 2005 was the same. I left home by 7am that day because I was travelling from Asangaon (70 kilometres by train), and set up shop as usual. I kept working although the road started flooding – I had junoon then. But the trains had stopped running, and I somehow reached home at 3 am. I don’t know how but I reached home.”

Others listening to this chimed in with equally distressing stories: some had joined human chains walking in the middle of the road as water swirled around them, some saw people being swept away in the water’s fury. Although they were happy to survive it, the monsoon brings back their worries as heavy rain, high tide and choked drains cause the water levels to rise. Most hope that they do not have to face the 2005 situation again but there have been a few close calls such as in June-July 2019, then in 2022 and this year.

The water bowls of Mumbai

Around 60 percent of Mumbai was under water on July 26, 2005, noted a paper[4] by Prof Kapil Gupta in 2009. Paragraphs outlining the day’s events and analysing the deluge concluded with the lack of sufficient rain gauges – only two at the time – which led to warnings being issued after it was too late.

The low-lying areas of Kurla, Sion, Dharavi and Bandra East were some of the worst hit because of their vicinity to the overflowing Mithi River, poor drainage systems, backflow owing to high tide – compounded by the lack of warning systems and early evacuation. The trauma of that day spills over even today for residents of Samarth Chawl, situated in Kurla along the Mithi. Wary and alert to the intensity of rain and rising water levels around them, their minds and conversations rally around precautions to take and escape routes, keeping their children close and precious papers in a carry bag.

Sujata Suresh Kakwal does not take a chance. Her family was sleeping on the floor of their modest home when it was inundated that July day. Since then, Kakwal has a routine she follows every monsoon. All their belongings are moved to available higher places — on tables, top of cupboards, on the upper floors, or stacked in a Jenga-like fashion. “The 2005 floods have made me anxious. We had to take shelter on the roof and waited until the water receded, and then slept in muck. The BMC has installed a pump so there isn’t as much water now, but we still get a foot of water on heavy rain days,” she says. Her neighbours have increased the plinth levels by 1.5 metres hoping to be safe if another flood occurs.

The Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) has installed 60 automatic rain gauges at 58 locations[5] that transmit data to the Disaster Control Room every 15 minutes. They also sound alarms if the rainfall intensity exceeds 10 mm within 15 minutes. It also installed 481 pumps[6] which are expected to dewater 25 wards in the island city, western and eastern suburbs.

The July 2005 deluge also prompted the formation of the Mumbai Disaster Management Plan[7] in 2007 (updated in 2022), which documents several “flood-like situations” in 2005, 2017, 2019 and 2020. It categorises the situations into three — localised flooding due to inadequate drainage, flooding due to overflowing Mithi river, flooding due to a combination of high tides and high river flow. However, these official definitions matter little to people who must brave the floods. Even with flood-response measures in place, people living along the city’s edges prepare for the worst every monsoon, relying on themselves rather than infrastructure.

Data[8] shows that that while pumps and drains are important to fix, strengthening institutional mechanisms, establishing emergency control centres, updating weather stations, removing solid waste and having response mechanisms in place is of importance too. It is reported that between 2010 and 2020, the BMC spent Rs 7,000 crore[9] on desilting nullahs and stormwater drain works. Unsurprisingly, there was a scam here too. In 2015,[10] the then civic chief Ajoy Mehta had ordered a probe against contractors and civic officials for shoddy cleaning of stormwater drains – after the monsoon flooded parts of the city.

Flood shelters but not for all

A study by the World Resources Institute found that only 46.5 percent of the city population is able to access flood shelters[11] set up by the BMC during heavy rain and reduced mobility. The 868 shelters have been set up primarily around Byculla, Girgaum Chowpatty and Grant Road, with some sparsely located in Bandra, Ghatkopar, Andheri, Mulund and Borivali. However, the Mumbai Climate Action Plan (MCAP) points out that areas with chronic flooding lack flood shelters.

According to the MCAP, over 35 percent of the city population lives within a 250-metre radius of chronic flooding spots as well. It also identifies high population areas like Deonar, Mahul, Kandivali East, parts of Powai and Andheri that lack flood shelters within a one-kilometre radius. This, combined with the fact that between 2017 and 2020 Mumbai saw a steady increase in heavy rainfall events. “We were living in the Bandra Government Colony in 2005, and water entered the ground floor of our building,” says a Mantralaya staffer, who was at Sonavne’s tarpaulin-covered shop.

According to the Chitale Committee report, around “20 lakh people were stranded in transit and an additional 25 lakh were under water for hours”. That’s a staggering 4.5 million people in need of shelters that day. Power stations and substations were submerged, cutting off electricity in most parts of the city. “We didn’t have mobile phones like today, we just waited for the family to return home,” remembers Javed, the taxi driver. Many were rescued through boats but many others were stuck on roof tops, bus tops, stranded on railway stations or worse, trapped inside their cars. The floods left behind destruction, distress and desperation.

The National Guidelines for the Management of Urban Flooding[12] categorise urban floods as the result of urbanisation that leads to development of catchment areas which increase flood peaks from 1.8 to 8 times, and flood volumes by up to six times. Mumbai’s current development trend that encourages more construction at the cost of natural ecosystems is directly affecting how much the city floods. Adding on to the inefficiency of infrastructure, the Indian Roads Congress’ guidelines on urban drainage pointed out that Mumbai drains are being designed for 50 mm of rain per hour – this means a lack of planning for future worst-case 2005-like scenarios.

How to deal with urban flooding

This paper[13] noted that there weren’t many attempts to study flood incidents before the 2005 Mumbai flood and the BMC was unprepared to handle such a disaster. It mentions that the deluge forced the NDMA to address urban floods as a separate disaster, leading to the formation of the National Guidelines for the Management of Urban Flooding[14] in 2008. These guidelines include an analysis of urban floods across India’s cities and a comprehensive list of actions that can be undertaken for capacity development.

Of the 23 items on the to-do list, establishing an Urban Flood Early Warning System is a priority as well. The Ministry of Earth Sciences planned to release an app called i-Flows[15] in 2022, which promised timely alerts of flood-prone areas six to 72 hours in advance. However, people do not know about it yet. Abbreviated to i-FLOWS for Integrated Flood Warning System which was installed in Mumbai in 2020, the system collects data from the automatic rain gauges installed across the city to provide weather updates, SOS emergency calls, and a direct link to the disaster management helpline number (1916). Similarly, the Climate Studies department of IIT Bombay has also developed an app for flooding data which is crowdsourced, called the Mumbai Flood App. Nineteen years after Mumbai’s worst flood, flood warning apps should have been a time-sensitive priority for the city. But have these reached people on the streets as they should?

The MCAP[16] also has a list of actions the city can and should undertake to reduce flood risk. These include increasing vegetation cover and permeable surfaces, and building flood-resilient systems and infrastructure. The study[17] also encourages the use of innovative methods of rainwater harvesting, filtration systems and green roofs to retain more rainwater than cities do currently. If these reflect on the development plan for the city, there is hope for Mumbai to be flood-resilient.

Till then, many like Javed and Sonavne live by their sheer luck on a day when the elements – and their city – let them down.

Shivani Dave is an architect, writer and illustrator interested in exploring the intersection of architecture and social sciences. After graduating in architecture from Mumbai, and in media from the London School of Journalism, she is applying the fundamentals of architectural research and writing within urban contexts to develop phenomenological ideas about life in cities. She researches, writes and illustrates in Question of Cities.

Illustrations: Shivani Dave