In 1996, my family moved to Pune’s green outskirt called Kondhwa with mountains behind us, grasslands, perfect weather across seasons, various birds – and an overall calm. In my teens, I would cycle to school through Camp’s lush and foggy forays while old Pune’s peths (locality or cluster) gently carried on. Today, the mountains have tall buildings, gutters are where storks once nested, tanker water is supplied everywhere, and there’s an overall collapse of infrastructure with blazing hot summers. Witnessing the brutal, haphazard decline of Pune has left a critical impact on my psyche as an artist, making me study patterns and structures of cities wherever I go, and this becoming a focal point of my writing voice.

I remember spotting painted storks where the ‘Sangam Bridge Dam’ today suffocates the Mula-Mutha river as it merges. They were gregarious, a large score of adults and juveniles, perched on the higher bank, right next to the road where cars and rickshaws passed by smoothly. Hundreds of bats circled that evening. Pune’s famous Boat Club underneath was just bullied by Grey Herons and Golden Orioles. In 2001, the river was unclean but its banks were relatively alive, plenty of large trees and open scrublands around it ensured biodiversity was sustained.

Downstream, towards Kalyani Nagar, Mundhwa and Kavdipat, I spotted Spoonbills and the occasional Greater Flamingo, even as late as in 2013-14. Few are aware but there’s an entire ecosystem that thrives on what the river offers, including people. For instance, a community who catches worms off the river that is later fish food. Of course, all this is now destroyed with the riverfront ‘development’ project, which, as rightly forecasted, has ruined the river.

Photo: Ishan Sadwelkar

Pune’s rivers that once blossomed are reduced to sewers, ignored by natives and new settlers alike. As much as 80 percent of the PMC supplied water ends up being sewage with 29 percent untreated and only 6 percent eventually recycled.[1] The Mula-Mutha contains three times the amount of permissible human and animal excreta. The rivers within Pune are the most polluted of the entire Maharashtra state, which itself has the highest river pollution in India.[2] Instead of cleaning and reviving the water, the projects have bunded it, built concrete banks and released more effluents into it.

Over my teenage and youth, I noticed the floods get worse with each passing monsoon, clogging banks with remnants of various kinds of solid waste. I also noticed a steady decline of Dhangars and similar communities who depended on the banks to graze livestock. Sometimes over the old bridges like Lakdi Pul and Bhide Pul, old Punekars alight in the evenings and reminisce, some on cycles, munch on roasted peanuts and call it a day, defeated.

Mixed ecosystems, different summers

Nestled on the Deccan plateau, Pune is replete with a variety of habitats: grasslands and scrub ecosystems, forests, wetlands, cultivation with hill ranges in the north, west and south. All different. The forests in the Western Ghats are one of the world’s most biodiverse hotspots. Towards the east, arid scrub, grasslands and oasis-like wetlands have antelopes, wolves, jackals, hyenas, raptors, migratory birds and rare seasonal flora. In the north, the Western Ghats diverge inward and several mixed ecosystems exist. Smaller wetlands, natural migratory paths and rural, indigenous livelihoods are found in all these regions.

In the early to mid-2000s, the IT boom[3] followed by the sudden invasion of corporates,[4] corrupt land dealers[5] in the city and a helpless loss of succession amidst old Punekars to carry forward their architectural, linguistic and cultural heritage[6] accelerated the decay of Pune. As a teenager, I noticed the bowels of the city, its fragile waste-paper markets, informal thrift shop chains, slummed misery, incompetent and dusty buses coughing into potholed lanes, and old inhabitants easily outnumbered by newer settlers who never seem to lack respect for Pune’s heritage and linguistic culture.

The other unfortunate and glaring change I noticed was a rise in temperature, a sudden onset of a blazing summer as opposed to a more pleasant hot season earlier. This, I have felt in my short life, and I am still relatively young. This year was, indeed, unbearable, reminiscent of the times I shot documentaries in Agra or Delhi during April, rationing out water for the film crew and praying no one faints from a stroke. In 2024, Pune’s summer temperature reached a record 43.3C.[7]

Point of no return?

The Pune Metropolitan Region Development Association drafted a 2024-2041 expansion vision. The strategy is mainly to incorporate nearby villages into the city’s boundaries and further infrastructural limits. This razes various natural habitats that exist within and around Pune city and the district. For instance, at present, the area of Pimpri-Chinchwad[8] city is 181 square kilometres; after the inclusion of the villages, it will be 237.72 square kilometres.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Like earlier, the expansion is faster than the speed of town planning, creating grey areas and potential loopholes for various illegal and wild card players to benefit from at the expense of ecology, livelihood, local heritage and overall liveability. The World Resources Institute places Pune’s expansion index as ‘moderate’ with a score of 2.2.[9] Across South Asia, cities are expanding more outward rather than vertically, and most cities are slated to double in volume by 2030.[10] Is Pune at a point of no return already?

Effectively, a Pune of the future could be a congregation of cities and towns with an arbitrary separation from whatever Mumbai expands to. An eventual succumbing of the Western Ghats and grasslands, and incredible rise in temperature and strain on natural resources will follow, or rather intensify. Urban expansion usually precedes the rate of population growth and the casualty is prime agricultural land, fertile/delicate ecosystems and wetlands.

The Mula and Mutha, in ancient times, had agrarian banks. Today, the rivers are sewers. I have been witness to various lakes and rivulets disintegrate. Pashan Lake, for instance, where we once went birding and cycling for fun, is now surrounded by random, populous buildings inching towards the water. The truly gorgeous and other-worldly plateau of Saswad with an eerie, foggy Purandar fort in the background and little farmlands in all directions, was spectacular. Now, everything is fenced, digging has begun, garbage necklaces the thin winding road, and cars honk in the crowded wind – wolves, hyenas pushed further away and glaring flex boards block the view of mountains. Sinhagad, which was once faraway, at a vantage, now has buildings festering at its feet with really no boundary between itself and the city. I no longer know what is what, where Pune lies and what Pune is.

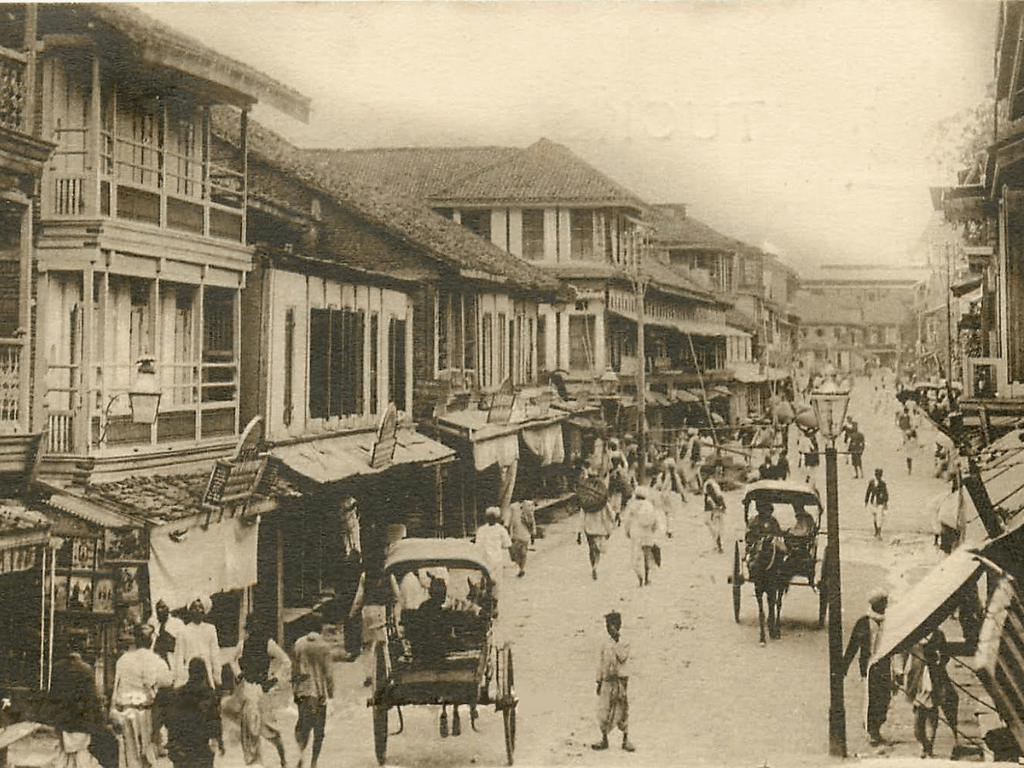

Pune started out as a series of hamlets along the Mula-Mutha, a row of fishing villages where potters, coppersmiths and traders aligned. Subsequent rulers fortified the city as they saw fit, enriching the banks with added or relocated peths for a more planned and segregated housing plan[11] to accommodate various communities and marketplaces. Eighteen peths made Pune. Complimenting this were the surrounding farmlands, granaries, forts, pilgrimage spots. The last of the Peshwa stronghold ended in 1818 just after the Vishrambaug Wada was built; soon, the Shaniwarwada was reduced to a British government office,[12] and, eventually, in 1826 a fire consumed most of its glorious inner construction.

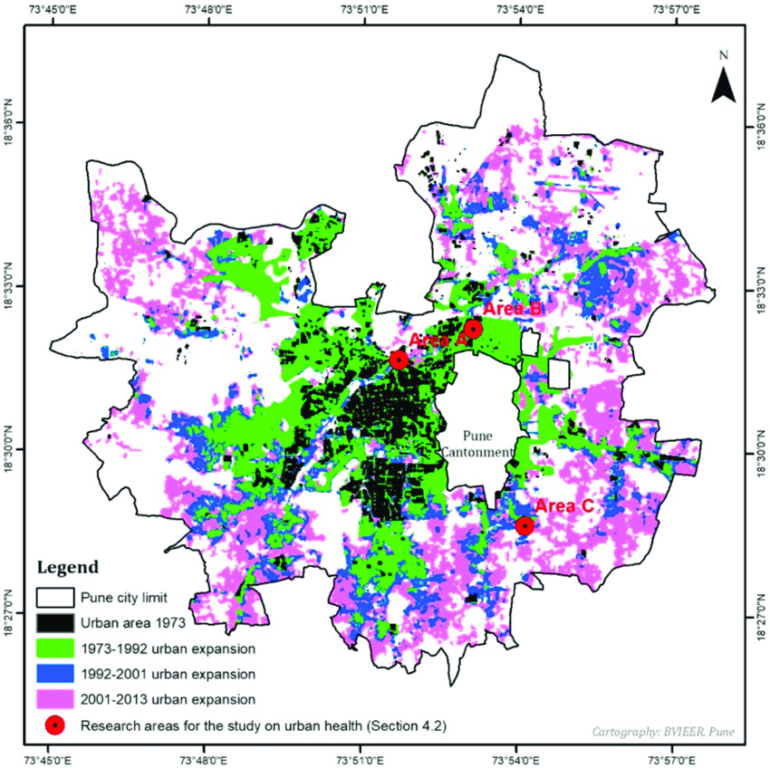

Pune’s expansion then ventured into the Cantonment, once land used to house the cavalry and extra supplies, and eventually Pune became a stronghold of the army. Post independence, Pune’s sister city Pimpri-Chinchwad saw a flux of industrial growth with TELCO (now Tata Motors) and other corporates building their plants.[13] This was followed by the industrialisation of Bhosari, Chakan, Pirangut areas – all large manufacturing hubs today. Come the 1990s and economic liberalisation spurred a further expansion for housing and IT companies that took off in the early 2000s.

The 2010s pushed the city limits further.[14] Hinjewadi, once a distant, hilly farmland with rivers, is a slew of skyscrapers for the IT industry. Wadgaon Sheri and Kharadi have been similarly compromised. Common in all these expansions is that at no point was Pune’s planning and governance as fast and prepared as the expansion itself. This resulted in lack of infrastructure,[15] laws, limits and an overall vision to comprehend or control this growing concrete obesity.[16] Does Pune have the roads, public transport, to hold so much?[17]

Photo: Nikeita Saraf

Natural boundaries

Importantly, what happens to the sprawling and rare natural habitats that once surrounded us, the dwindling of delicate ecosystems with apex predators like the Indian Wolf.[18] Towards the Western Ghats, ‘prime real estate’ continues to destroy the lush, sacred belt of Mulshi. Panshet, home to endemic flora and fauna, provides ‘dream homes’ in ‘the lap of nature’ for privileged urbanites who want to eat their cake and have it too. The Great Hornbill[19] and rare frog species[20] are still spotted at Tamhini Ghat but reckless bikers and tourists scream around half-naked in rain throwing plastic and liquor bottles into the waterfalls here. In Mulshi, an almost surreal stripping of the forest was done to house complexes like Lavasa, resulting in a cultural divide and ecological conflict.[21]

Apathy towards a city or region’s nativity is rather common across India. Cross-cultural respect and, importantly, acclimatisation into a new state or region’s language and heritage are now rare. Those working in air-conditioned offices are often removed from the local culture, distant from the finer nuances and threads of the region. Apathy towards ecosystems is ever more fervent. Grasslands and scrublands are perceived as ‘wastelands’ making Pune’s destructive expansions not as glaring as chopping down a forest, for example.

I have heard old-timers narrate Pune’s boundaries: Saras Baug being the edge beyond which lay a garbage dump, Parvati hill a trek with that quaint, lovely temple clotting at the top amidst babblers and owlets. This is interesting because a major signifier of city limits is where houses of marginalised groups are clustered; Parvati’s foothills have a substantial number. This is true for slaughter houses, tanneries, informal waste management and recycling hubs. Fast forward two decades. These settlements, whether at Parvati, Hadapsar, Kondhwa, Lohegaon, have merged into the city. Likewise, industrial hubs that once released effluents at the periphery now neighbour housing complexes and wholesale food markets.

The problem is that there is little real development — public transport, sewage, waste management. These mark the status and liveability of a city, making it great. Just constructing repetitive cubicle apartments and malls wherever possible, and cramming them with air conditioners is not modernisation. For a city or civilisation to be modern, it has to lead the time in which it exists; Harappan towns, for instance, had planned sewage and sanitation. They were, in a sense, more modern compared to what Pune or similar cities are today. We lack efficiency in the use and reuse of resources, like how Indore recycles wet waste to fuel its buses.

Dystopian future

Pune claims to be an intellectual city but it has, for long, surrendered to a ghastly bus system. Trains, metros then? The metro could have been underground to preserve whatever little beauty of the city there still remains, instead it runs like a big airborne sewage pipeline parallel to the sewage-filled Mula Mutha, in the process masking the city’s skyline and heritage structures like the high court, old bridges, Fergusson Road and so on.

Photo: Ishan Sadwelkar

This is symbolic of a dystopian future, not a thriving and beautiful, green one. For a city that prides itself on cultural heritage, the old city’s architecture is poorly preserved; there is no concern to preserve the outer facades, brick structures, old stone structures, articulate and rare woodwork. The fall – or concrete rise – of Pune reflects in the state of its rivers, hills and grasslands as sewers, buried mounds and dumping wastelands respectively. As pessimistic as this sounds, it is true.

Photo credit: Carsten Butsch/ResearchGate

Split this expansionist journey into decades – from 1971 to 1981, then to 2001 followed by a sudden growth which turned intense. From 2013 to 2023, the annexed regions of Pune’s city grew more than before.[22] A growing population, privileged people relatively unbothered, oppressed people who don’t have a choice, and nature which we never gave a chance to.

We can start by cleaning and maintaining Pune’s lifeline – its rivers. Then, on an urgent war footing, the hills and grasslands need to be declared designated protected areas, not just for the incredible biodiversity they house but also because they act as ‘shock pads’ for the monsoons and summers, ensuring the city does not suffer floods or extreme heat. For similar reasons, the Western Ghats region must also be declared as fully protected areas, with strict limits on construction. Then, the city’s progress will have to be its waste management and efficient infrastructure where waste can be repurposed into improving life.

Pune suffers from a sewage issue and disproportionate use of water. This can be remedied by implementing more sewage treatment plants to attain a Water+[23] status to maximise the reuse of ‘waste’ water and re-releasing treated water into the river. The elimination of manual scavenging is of utmost necessity and links directly to sewage treatment. An overall, more formalised approach towards waste management and transport will ensure that marginalised communities and low-income individuals currently working in the informal and dangerous sector will lead better lives, and the overall liveability index will improve, and problems the city faces will subside.

If things go on as they are, myopic and unregulated, the future is unbearable and concrete. But Pune does have a past of glory, a city that has seen reform and growth. One hopes that the decay is arrested and this pleasant town grows in the right direction instead of straying in every direction without a vision.

Ishan Sadwelkar is a filmmaker, writer, and researcher who has explored and extensively written about the city. His written work has featured in national publications. An assistant director on films and a documentary filmmaker, he combines his passion for studying culture, heritage, food with his great love of nature. His earlier writing for Question of Cities can be found here.

Cover photo: The postcard photograph shows a street in Budhwar Peth, Poona.

Credit: Wikimedia Commons