In a city that was built on the back of textile manufacture and trade, what aesthetic would the old textiles market have and what would it say today more than 150 years later? Mumbai’s Moolji Jaitha Market, popularly called MJ Market, stands like many edifices around it as the centre of a hyper-frenetic activity even today, its columns and arches showing their age, its alleys spilling out and across Kalbadevi that holds this and other old bazaars of the then Bombay, its sounds and smells conveying a curious mix of then and now.

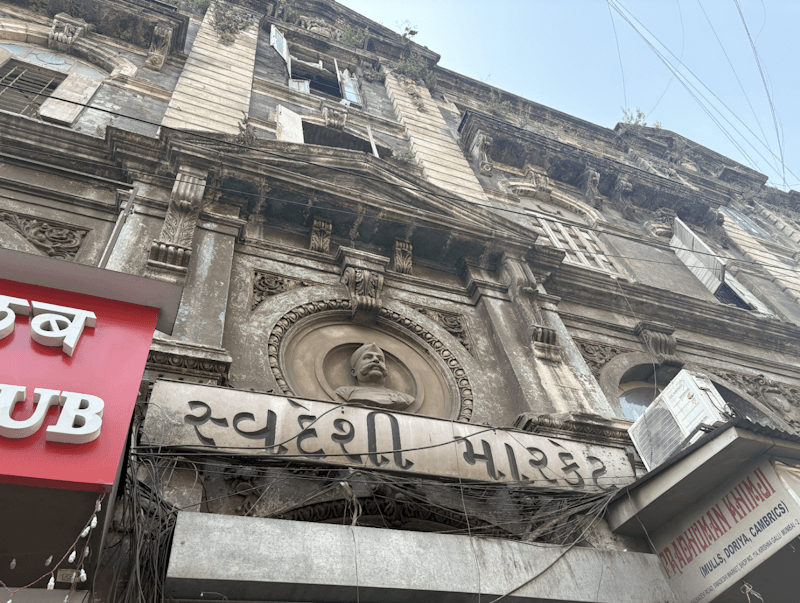

To walk its alleys and paths without imagining the earliest of traders, the boldest of them like Dhirubhai Ambani, is not easily achieved. History is stone-written into this site sprawled across nearly four acres in what used to be the market district of British Bombay. Nearly 1,000 little shops – raised cubby holes or shacks with support – with commonplace signs, prosaic tube lights, mattresses wrapped in the traditional whites, voices shouting prices – make up this market. It might have been similar back in the days, perhaps fewer tube lights.

To imagine the MJ Market with its chaos and commerce giving way to a new form is not easy either. Redevelopment, knocking on the archways of the Market, is a dreaded word for some old-timers here but welcomed by others. There is a buzz about it but no concrete plans yet. If the redevelopment keeps the architectural and design integrity of the market within its precinct, with a nod to modern additions, it would be welcome; if the apex body of the MJ Market pushes ahead with the standard tropes of redevelopment prevalent in Mumbai, the remnants of the oldest among Mumbai’s markets may be erased.

The better photographed and more Instagrammed Crawford Market that draws tourists too was listed for redevelopment. A blend of Victorian Gothic architecture and other European styles with Indian influences, it stands out for its location, its frontage, and the unmistakable clock tower. Its redevelopment was much debated; the redevelopment of the MJ Market less so. The Crawford Market redevelopment involved the construction of new structures to house fish vendors from nearby, an one-acre open space with a pedestrian plaza, restored fountains, and an amphitheatre besides the restoration of the existing markets and the offices of the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation.

The MJ Market redevelopment, when it happens, would define the area of Kalbadevi, the hub of old-time trading and commerce in Mumbai. Perhaps, its future can be glimpsed by walking across its past on a balmy Mumbai morning. This we did with Savitha Suri, author, researcher and textile heritage expert; and Tinaz Nooshian, cultural researcher, editor and writer. It is quite something to ‘see’ the MJ Market through their lens. That the market was built by ‘natives’ in colonial Bombay and it thrived is important; equally important is how its aesthetic was shaped not merely by structures but the interactions of people within it.

The market and the precinct

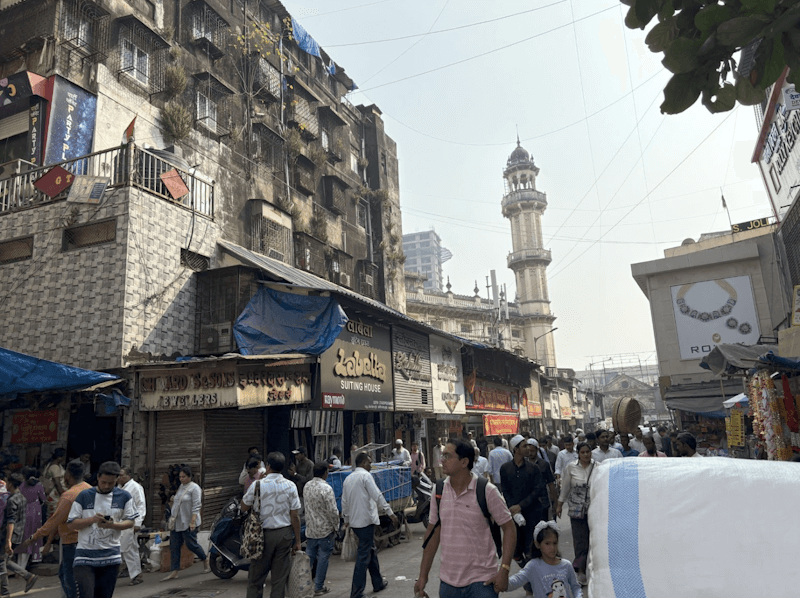

The MJ Market belongs to another era, historically and architecturally, Indian in its façade and appeal though it belongs to the colonial time. It’s a part of Kalbadevi which with its many markets – Mangaldas, Zaveri Bazaar among them – used to be the nerve centre and the backend of the imperial trading city that the British constructed. The former Cotton Exchange building, the very name says it all, is situated in the vicinity of the MJ Market, at the junction of Kalbadevi Road and Sheikh Memon Street.

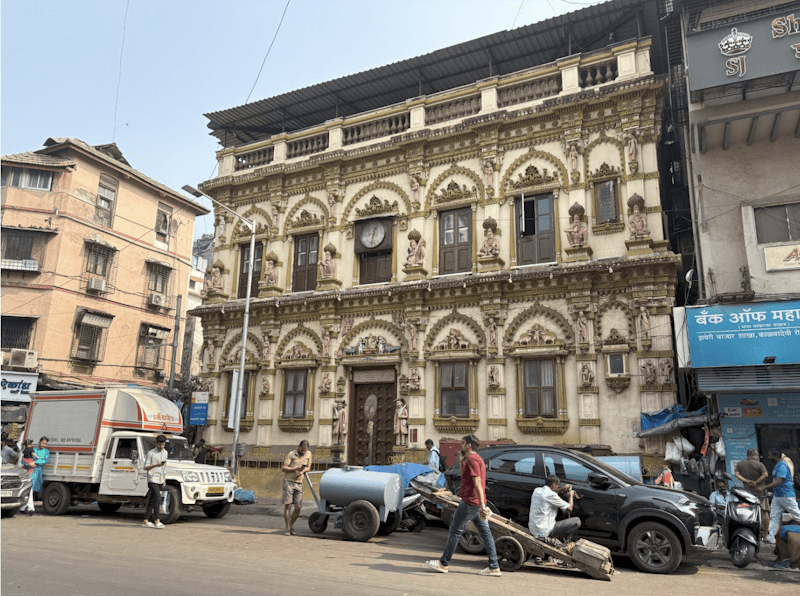

Once the headquarters of the East India Cotton Association, which was formed in 1922 to fix standards of cotton classification, regulate its import and export, and adjudicate in conflicts between traders, the building was constructed in 1938 in Art Deco style – the then modern expression in contrast to the Victorian and Gothic colonial buildings. It features motifs representing various steps of the cotton trade from sowing and reaping to spinning and packing; some of these are sadly hidden behind large LED screens now. The stately steel frame, story-telling in bas relief, the chhatri at the top are reminders of that.

The Cotton Exchange building, Suri points out, became the inspiration for other structures in its vicinity, especially the ones to do with cloth trade and business, including parts of the MJ Market. This is where the architectural aesthetic becomes interesting. It’s a blending or fusing of the imported Art Deco and home-grown styles that the Halai Bhatia traders – the dominant community in the cotton trade – carried with them from their native Kachchh. This curious mix of design, borrowed and native, layered with people’s use of the space and stories, mirrors a strong sense of ownership within colonial Bombay.

“Colonial markets like the Crawford market were usually located at the junction of where the native town started and the colonial town ended, so it became a vantage point. The surrounding area is basically residential areas which cater to multi-use,” says Vikas Dilawari, a practicing conservation architect, involved in Mumbai based restoration projects including of the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya and the Flora Fountain.

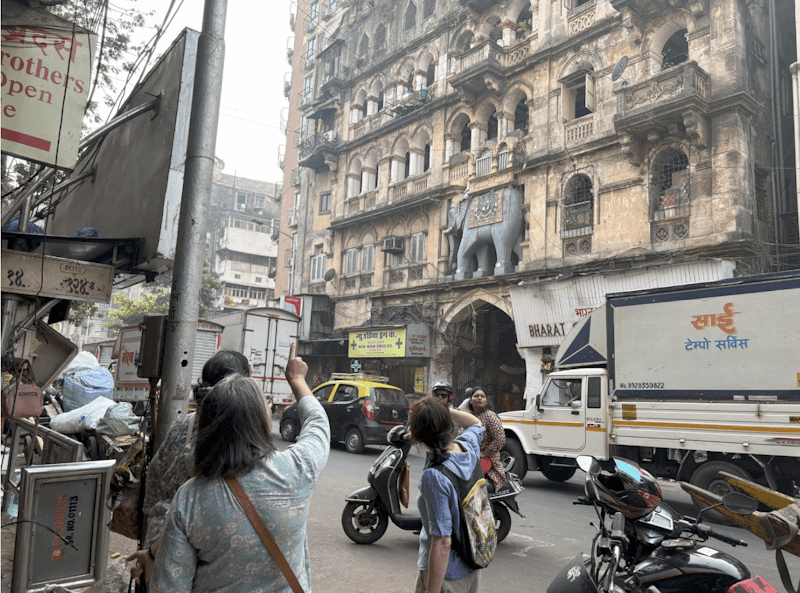

We enter the market, with Suri and Nooshian unspooling vignettes. Handcarts piled up with bales of cloth still ply the narrow streets, somewhat asynchronous with the modern gadgetry and AI use around. Tempos are lined up to transport the bales. Across the street from the MJ Market stands the Dwarkadeesh temple built in 1875 by the Halai Bhatia men who had left their families back home in Kachchh and yearned for a piece of familiar surroundings here at their place of work.

“The clock on the temple is in Gujarati so that they could read it in a city whose language they could not always understand. They felt the need to create this, bring alive the trees and monkeys of their home by carving them on its façade. The native parts of Bombay were essentially designed and built by and perhaps for migrants,” says Suri which explains the different aesthetics in different older parts of the city. The temple is an intrinsic part of the market precinct. The pichwai inside is a reminder that the aesthetic of a city or an area is less a pre-determined imposition of the power of the day, more an expression of people’s needs, aspirations and desires.

For the men whose work – and life – was the cotton and textile trade, their buildings sport angels with wings and Corinthian columns. Over time, as these clustered, they altered the demography and the vocabulary of the city – literally and architecturally. Besides the Dwarkadeesh temple, the Nar Narayan temple and the famous Mumbadevi temple show variations of the blending of native and modern styles. The MJ Market, named after a wealthy trader, is a fusion of Victorian-Gothic elements with Indo-Saracenic ones, the latter visible in its domes, minarets, and jali work. The MJ Fountain was, in fact, designed by FW Stevens, the British architectural engineer known for his design of today’s heritage structures such as the Victoria Terminus (now Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Railway Terminus), among others.

The open layout

Unlike a massive mall, the MJ Market was not one building or even a cluster of buildings, contained or circumferenced. Instead, it was a tapestry of lanes and gullies – nearly 30 of them – which opened out to the world outside and culminated in small chowks, almost a mini-city. It’s still an open and porous space with every street clustering traders, lanes and gullies opening out and merging with each other, and spaces set aside for worship, rest and recreation. This quietly shows that town planning, in its larger sense, was not restricted to the areas that the British occupied in the colonial city or the town improvement schemes they introduced after Bombay was beset by the plague.

“Even today, nothing has changed about these markets. It becomes a very important part of what we are looking at in terms of how neighbourhoods were built then. They were built for communities predominantly working and living there. The homes would be like the Mahajanwadi, which is for the Halai Bhatia community, an accommodation complex or a wadi being built with everything and for a community-centric lifestyle that they were used to back home,” explains Suri as we enter one of the gullies.

The MJ Market is like a grid of 24 entrances and intersecting lanes such that they lie at right angles to the main road. This offered, according to Suri, an open rectangular layout and the traders did their business with signs at a lightning-fast pace or gestures under a roomal (handkerchief). They would sit in the open and trade, but no one would find out the deals were made or pick up trade secrets. The use of codes and gestures specific to the market, also made it a closed community, though not always harmonious.

Traders parked themselves at the shopfronts or trading stalls, welcoming customers who walked in any time. The layout was mostly at the eye level making the space less intimidating, more welcoming. Back in the day, before the climate change-related spikes in heat, the market’s ventilation system with windows and intricate jaalis located high near the ceiling ensured effective air circulation and natural light. When electricity had not reached here, traders would work till sundown and head home at sunset, Suri says.

The future uncertain

This layout and set of elements do not make it possible for air-conditioners to be installed, especially on lower floors, and the electrical wiring network has become rather outdated. Here’s where the aspirations and desires of today’s traders become important; they would like air-conditioned, compact, closed offices and shops. “Anyone who gets an opportunity to redevelop at this point is going to take the chance because they want to upgrade conveniences the way they have upgraded how they do business. Now, from my interactions with the traders, the focus is on customer-friendly layout and ACs whereas back in the day it was about building an environment they were familiar and comfortable with,” points out Suri as we pause for tea in the central part of the market.

“Hardly 30 percent of the cotton textile trade is functioning today, otherwise the MJ Market is a dead or declining market currently from a retail perspective. Businesses have either moved on completely or are in the process of doing so,” remarks Suri, “those who remain here have told me ‘you can talk about the history and architecture of this market because you don’t have to work from here’. Women who have worked here or have had relatives working here pointed out to her the absence of rest rooms for both men and women. “Someone asked me ‘how are you going to work in a space that offers such little dignity’ and that makes sense,” she adds.

For many in the MJ Market, it is just a piece of real estate now. The Datta Samant-led strike of textile mills’ workers in 1982, among other factors, led to the closure of many mills and massive tracts of land were later monetised; Mumbai’s pre-eminence in cloth manufacture and trade dwindled. The shift shows in the trading of spaces in the MJ Market – earlier, only a Halai Bhatia community person could purchase a shop or gala here, if not inherit it; now many of these have been sold or leased to non-community persons.

“I do not fantasise about heritage buildings but whatever was done in the past, I believe, was the effect of good planning. Now, the unfortunate part is that planning has gone for a toss. If the quality of life and the overall planning are kept in scale, then we can have a better city. This is where conservation used to help,” says Vikas Dilawari.

We are at the end of the walk. We turn at the Cotton Exchange and see the MJ Market – and others around it – for what they are: Emblems of an era long past, enduring but on the cusp of change and redevelopment. How many elements of the old will prevail in the new and what the apex body of traders imagine the new MJ Market to be is the big question. “Redevelopment needs to be careful, empathetic and useful,” reflects Suri, “It’s not just the loss of a built form but a loss of livelihoods, labour and memories too.”

Nikeita Saraf, a Thane-based architect and urban practitioner, works as illustrator and writer with Question of Cities. Through her academic years at School of Environment and Architecture, and later as Urban Fellow at the Indian Institute of Human Settlements (IIHS), she tried to explore, in various forms, the web of relationships which create space and form the essence of storytelling. Her interests in storytelling and narrative mapping stem from how people map their worlds and she explores this through her everyday practice of illustrating and archiving.

Jashvitha Dhagey, a multimedia journalist and researcher, is the recipient of the Laadli Media awards for three years in a row – 2023, 2024 and 2025 – for her work in Question of Cities. She holds a post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic and is presently pursuing her Masters in Urban Studies at the Indian Institute for Human Settlements, Bengaluru. She observes and chronicles multiple interactions between people, between people and power, and society and media, and developed a deep interest in the way cities function, watching Mumbai at work.

Cover Photo: One of the narrow gullies inside MJ Market.

All Photos: Jashvitha Dhagey