Housing, especially mass affordable housing, is among the perennial issues that has plagued Mumbai. The city’s Development Plans (DP) and Development Control Regulations (DCR) have determined how and what is built across the city, and how the built environment accommodates – or does not accommodate – people. Over the decades, regulations have left an indelible mark on the city’s housing. “The DCR started off as building codes that were first imagined as a response to Bombay’s plague of 1896. People realised that unsanitary conditions were aggravating the spread of the flu and helping the spread of the plague,” explained Mumbai-based architect Sameep Padora. Studying the trajectory of how regulations impacted housing, shaped urban form and structures in the city, he put together his observations in the exhibition “(de)Coding Mumbai” that was on display in June this year.

What impact have the Development Control Regulations left on development and redevelopment over the years, and how?

The Development Control Regulations (DCR) started off as simpler graphic building codes first designed in response to the plague of 1896. This is where the timeline of “(de)Coding Mumbai” began. The Bombay Improvement Trust realised that unsanitary conditions were accelerating the spread of the plague. To combat it, building codes were introduced. The light plane angle (the plane at which the light comes at a building in all weather) or the rule of 63.5 degrees distance between buildings to ensure adequate light and ventilation was one such code.

The building codes started off being about lighting, ventilation and creating environments for better health of the city’s residents but their original intent was lost over time. Now, codes are subjective and exceptions to them are transactional. When you design a building on a plot in the city, you need to hire municipal architects to liaise with the authorities and to decode what the DCR could mean. A lot is based on exemptions and subjectivity.

Building codes have gone from being about health and sanitation to quantifying real estate, in which the municipal architect finds more leverage than the design architect does. It’s an exercise in financial manipulation, it benefits all except perhaps the end user especially in the low income or affordable housing. The fact that different rules apply to different people is apparent from how you can visually tell an SRA building, where slum dwellers are re-housed, as opposed to the saleable homes on the same plot. These differentiated experiences clearly denote the trajectory of the DCR – from being about the health of residents to merely quantifying or maximising real estate potential.

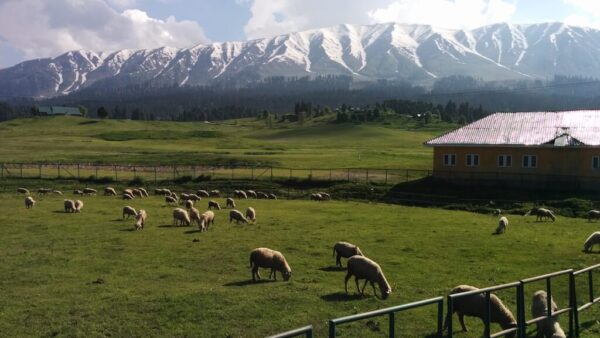

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

What are the problems with the current DCR?

Mumbai’s DCR is so convoluted and layered that it is opaque, its opacity is its biggest problem. The DCR operates at the level of an individual plot and the DP operates at the city-level, but there is no conversation between the two. There is a failure because of the disconnect.

Every developer should be asked questions such as what the constructed building contributes to the neighbourhood, how much energy it consumes, whether the carbon footprint is lowered, and so on. We need such mechanisms to gauge the vitality of a project. We also need typological mechanisms.

For instance, what if you were to get rid of the front setback or plot setbacks so your building could go right to the edge of the plot, but in lieu of that the developer converts the ground area into an arcade for people on the street to walk? You get a covered walkway that’s actually a public space on a private plot. A string of these creates public infrastructure, an urban fabric sympathetic to the neighbourhood and the street. The building code, however, doesn’t have that conversation.

Your exhibition looked at projects over the years. What are some of the drawbacks of the redevelopment projects?

I think these projects fail on two counts. One is at the scale of the neighbourhood and the city where they create no impact whatsoever. If anything, they make the condition worse. The podium parking lots is an example which was illustrated in the exhibition.

If this is the standard redevelopment format, you will eventually get streets that are completely disconnected from any kind of life because the only interface between the liveable space and the street will be the parking lot.

The second point of failure is at the sale of the plot itself. Redevelopment is primarily a means to quantify the “financial potential” of a plot. There is no qualitative index that it addresses of liveability or user experience. I’m not talking about an aesthetic here, but primary parameters of access to light, ventilation and social space.

What purpose do redevelopment projects serve?

There is a depleting building fabric. A lot of the housing stock that was built in the early 1980s was built with poor materials because the availability of good building materials was limited. So, there is definitely a need to redevelop. But what the nature of redevelopment will be is something we have to ask ourselves. Besides demolition and reconstruction, repair and retrofit are options as well.

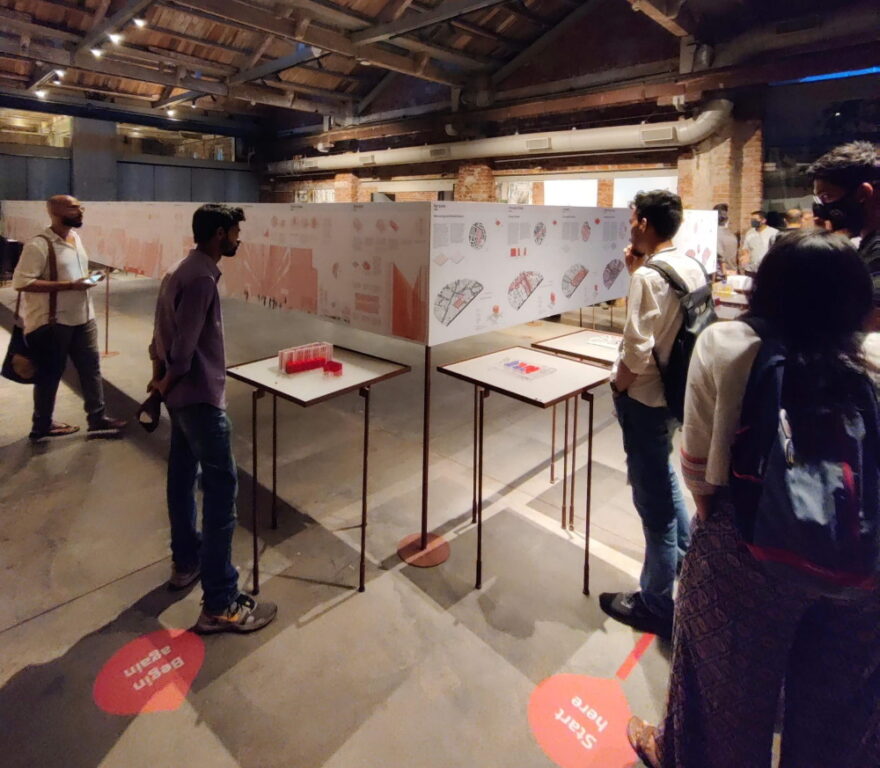

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

Are there elements from the projects you studied which can or cannot be emulated in the future?

To a large extent, I hope not. There is clearly a class division in the way that housing is structured in Mumbai and the type of houses being built for the rich compared to what are built for the poor. I’m hoping that that doesn’t carry forward, that’s something we can reconfigure.

Importantly, the state needs to stop thinking like a developer and rationalise the environments being built. It can do this through an active role in the development process through MHADA and SRA, or through a passive role where they set qualitative parameters or regulatory frameworks which developers need to benchmark against.

What are the ways in which DCR can be improved to make housing more equitable and sustainable?

There are so many things that I don’t know where to start. For example, the DCR makes complicated assumptions almost implying that if there is common space adjacent to an apartment then residents will enclose it. This is fallacious.

In the Charkop project which I studied as part of (de)Coding Mumbai, 27 houses open up to courtyards, but despite the fact that they have a limited built-up area, none of the residents enclosed any of the open space. They still use it as a common resource after 35 to 40 years. If nothing else, the people who write DCR should learn from these models of housing.

We need to start thinking beyond space in the mono-cultured BHK format where a corridor is only transient space. Spaces in between our houses are as important as the house itself. In some senses, COVID-19 taught us that we can no longer live with a limited understanding of dwelling. I think building codes have to start talking about program types, not from the lens of where we are today but what the world will be in the future. They have to be pre-emptive and forward-looking for 30 odd years, say 2050.

What are some of the things you have in mind?

The recent map of flooding and rising sea levels due to Climate Change already estimates that almost 50 per cent of Mumbai is susceptible to floods. We need building codes to have resilience strategies for all development. Maybe all these car parking podiums will turn into parking space for boats and amphibious vehicles? I’m joking but my point is that we need to think through this now.

Let’s also look at social housing in the Public-Private-Partnership format of the SRA. On the face of it, there is free housing for slum dwellers with an equal amount of square footage to rehouse them as what the developer sells in the free market on the same plot. However, that equal division does not apply for the plot; it is only exercised in the built-up area. So, what you get is a large number of people, the slum dwellers, living on a very small portion of the plot with a density that’s almost 10 times the original slum.

Now imagine people being warehoused into ground+20 storey towers where buildings are at a distance of 15 feet from each other. They are living in conditions far worse than in the slum. The “Doctors for You” report of 2018, included in “(de)Coding Mumbai”, found that every fifth resident of some of these rehoused colonies was suffering from tuberculosis and other respiratory diseases. It squarely attributed these to the design of these buildings. This is pre-COVID, you can only imagine what happened post 2020.

How can plans for individual plot-based housing be incorporated into the DP?

The neighbourhood scale is perfect, it dovetails into the political structure of the local representative or the corporator who can take inputs from local resident groups, translate them and bring them further up within the bureaucratic-political chain.

The edges of these various blocks then interact to resolve issues of overlap. Start at the level of the neighbourhood to see what it needs. Then see where these need to dovetail within other neighbourhoods, and so on. It would mean educating the corporators and other political representatives, it cannot happen overnight. But start at the level of the neighbourhood and go upwards.

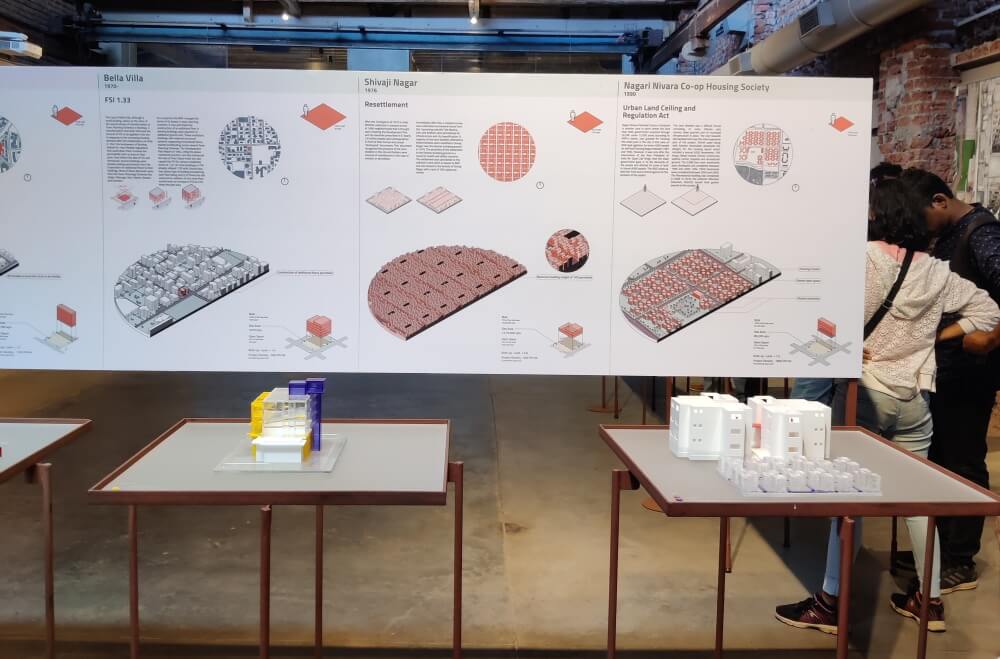

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

We have used FSI as a measure of development. What is your view on that?

We all know that the only thing that the Floor Space Index (FSI) has been used for is to measure the amount of sale area that a developer can get. It has no bearings on density because, obviously, more FSI would not necessarily mean more people. It could be six-bedroom apartments or duplexes which don’t translate into greater density. I believe that density is a much better operational idea than FSI. As I said, we should ideally move to a transparent format of development, form base building code, and use density as a means to assess what that development could be.

What changes would you like to see?

The idea of the disconnection between people and their surroundings is multi-scalar. Today when I live in a building and park cars in its podium, I get into my car at that level, speed over the coastal road or the sea link, and get to my podium car park at work.

The entire structure of development is built on disconnection – with your neighbour and city. New buildings are advertised as “Miami in Mahim” or “Upper Cuffe Parade in Wadala” where that disconnection is presented as an USP. These are development archipelagos but the city is beyond these archipelagos and cars. So, one way out is that the experience of the city needs to be closely tied to your everyday routine. We need to upgrade the city in between our workplaces and residences. Until we don’t start looking at the integration of a building with the neighbourhood, connecting people to their surroundings is not going to be possible. This is the big change that needs to happen.

Jashvitha Dhagey developed a deep interest in the way cities function, watching Mumbai at work. She holds a post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic. She loves to watch and chronicle the multiple interactions between people, between people and power, and society and media.

Cover photo: Jashvitha Dhagey