For the fortunate Mumbaikars whose apartments overlook the coast, the Bandra Worli sea link became the marker of how bad the city’s air was – its iconic outline barely visible on the heavily polluted days. Those who could see vast stretches of the city from their balconies and windows often found that the haze made the skyline nearly invisible. For millions whose view of the city was mostly from the ground level, there were other markers such as increased incidences of respiratory ailments, incessant coughing, frequent visits to the neighbourhood doctor, and the grim realisation that the masks which were bought to keep the Covid-19 virus at bay had to be used to filter the ganda hawa, or bad air as it has been colloquially called.

From November through February, Mumbai has had the worst air quality in many years. The city had long compared itself favourably with New Delhi which had earned the dubious reputation as one of the top three polluted cities around the world. The Arabian Sea helped sweep Mumbai’s pollutants away and cleansed its air in ways that natural ecology silently does. This advantage has steadily diminished – Climate Change has influenced changes in wind patterns and speed, as studies have shown – at a time when pollutants in Mumbai’s atmosphere have steadily increased.

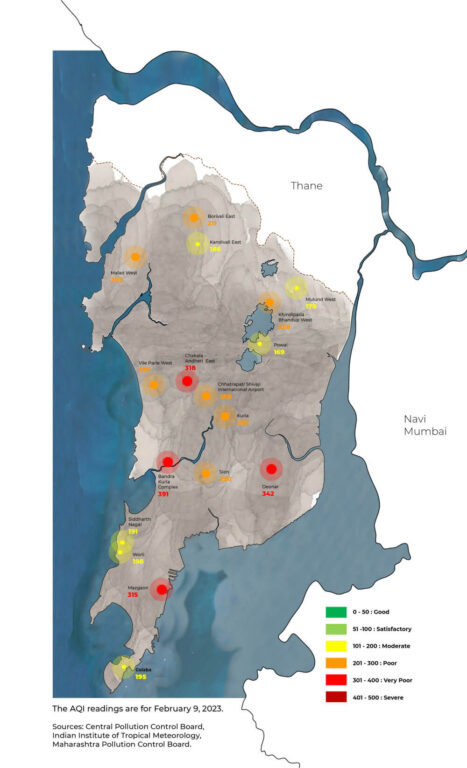

This February may well rank as the worst polluted in many decades with Air Quality Index (AQI) readings falling from ‘poor’ (201 to 300) to ‘very poor’ (301 to 400) and bordering the lower end of ‘severe’ (401 to 500) on several days. Nine out of the month’s 17 days recorded very poor quality air, making it hazardous for the city’s nearly 20 million. What is worse is that there were no days with ‘good’ (0 to 50) or ‘satisfactory’ (51 to 100) AQI readings for at least three weeks of the month.

These readings came on the heels of AQI numbers in January which saw the index touch ‘very poor’ on two days and ‘poor’ for nearly 13 days. The consistency of high and hazardous AQI readings stood out in stark contrast to the last two years in which there were only two days each in February with bad air quality. Clearly, air pollution was no longer an issue that Mumbaikars – mainly its authorities in the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) and the state government – could relegate to the back burner.

Road and construction dust, and vehicular emissions are the main sources of air pollution in Mumbai contributing more than 70 per cent of the Particulate Matter (PM) in the air, according to National Environmental Engineering Institute (NEERI)-led study in 2021; airport operations, garbage dumps, industrial emissions make up the rest. The dust is literally everywhere. The top three sources contributed only 28 per cent in 2010. It is clear that massive construction and demolition activities, including infrastructure projects and thoughtless expansion of road or private transport burning more fossil fuels, have come at a huge price.

Photo: Imtiyaz Shaikh

Public health emergency

The alarm was visible in the rash of online petitions that Mumbaikars circulated and signed demanding that the authorities take immediate steps to keep the pollutants under control. The petitions urged the authorities to implement what was in their domain such as capping construction and road dust. There was a nine percent year-on-year rise of home registrations last year; in addition, there is large-scale commercial and infrastructure construction across Mumbai. This ‘build-more syndrome’ is worsened by the BMC’s recent move to construct car parks under the city’s gardens and green spaces in which the tree cover would be further endangered.

The BMC’s annual budget 2023-24 laid out some relief measures and chief minister Eknath Shinde’s suggested that Mumbai be fitted with air purifier towers. While these may provide localised and temporary respite, they do not point to a comprehensive and long-term solution.

The government and the BMC are not responding to air pollution as a public health issue. Consistently high levels of pollution may well qualify as a public health emergency on the lines that the Covid-19 pandemic was; instead, the approach is to throw a few pennies and programmes at a complex issue. There is evidence of deaths related to or caused by air pollution; in 2020, the year of the lockdown when air quality was not as bad, a study by the Greenpeace Southeast Asia had calculated nearly 25,000 deaths in Mumbai linked to air pollution. The fatalities in Delhi were twice as much but that is hardly a consolation.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that there are more than seven million premature deaths every year associated with exposure to air pollution, that nine out of every 10 people around the world living in cities are breathing less than optimal air, and has urged governments to treat air pollution as a public health issue. Consistent poor air quality, its studies show, affects the respiratory system, and makes people more susceptible to other ailments, including cancer, neurological disorders, cardiovascular diseases, as the toxic particles move in the bloodstream.

If motor vehicles or airplanes had defects which caused a tiny fraction of these fatalities, there would have been a worldwide furore and the vehicles called back, compensation offered, and so on. But deaths due to or linked to air pollution barely cause a kerfuffle in governments – or even among people. The authorities see air pollution as a minor seasonal problem – nothing more.

In large cities such as Mumbai, the health impact of air pollution is not evenly felt. Those who can afford air purifiers at home and in offices, or frequent trips away from the city, are better placed to counter it. Millions who take public transport every day, work outdoors for long hours such as police personnel and delivery executives, labour on construction sites or garbage dumps directly inhaling the bad air can least afford mitigation measures – or the treatment when they take ill. If tagged a public health issue, or public health emergency during its worst period, the authorities have to assume responsibility for medical care.

Map: Maitreyee Rele

Band-aid on a bleeding wound

In the BMC’s seven-step plan to combat air pollution, called the Air Pollution Mitigation Action Plan (APMAP), Rs 25 crore or just about half per cent of its annual budget of Rs 52,619 crore for 2023-24 has been set aside. BMC administrator Iqbal Singh Chahal announced that “better practices” will be adopted for construction and demolition of buildings, specific measures to reduce dust on roads, creation of urban greenery, encouragement of clean transportation and sustainable waste management practices, and so on.

At this stage, when ‘poor’ to ‘very poor’ AQI days abound, the BMC is still planning to set up dedicated air quality monitoring units at the ward level, install 14 air purifier towers each of which can purify air within a one-kilometre radius, and mount air purifying filters at five locations which record high amounts of carbon emissions due to heavy vehicular movement such as the Dahisar and Mulund toll nakas, Kalanagar, and Haji Ali.

More data will help localise the issue because not all areas of Mumbai are equally polluted. On a given day, when the average AQI for the city hovers in the 200s, there are areas relatively cleaner with an AQI of 80-100 and areas far more polluted with AQI of 300+ such as Andheri East and Bandra-Kurla Complex.

It must be noted that these are still plans on paper; action is still some distance away. Besides, the experience of the cities which fitted air purifying towers or filters is that they offer limited respite and cannot constitute long-term resolution of the problem. Even if all the relief measures announced are implemented, it would be a classic case of band-aid on a deep bleeding wound, considering how widespread and deep-rooted the problem is.

What is appalling is that the BMC has not seen it fit to inform Mumbaikars on a regular basis of the pollution levels in areas across the city, and the steps it will take as part of the emergency response mechanism. Like Delhi’s Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP), a set of measures mapped to the AQI categories such as ban on construction during bad days, it was possible for Mumbai and Mumbai Metropolitan Region to adopt their own. In fact, the Maharashtra Pollution Control Board (MPCB) had drafted a plan two years ago. Why was the GRAP not implemented, why did the BMC ignore warnings of high pollution this year?

Photo: Maitreyee Rele

The missing link – ecology

Caught in the minutiae of measuring air quality and installing filters, just as the authorities are missing the link between air pollution and public health, they are ignoring – wilfully or otherwise – the important link between air pollution and ecology. Mumbai’s rivers and waterbodies, forest and tree cover, all dimensions of its natural areas hold the key to understanding the issue and showing the way forward towards a comprehensive and long-term response plan.

Air pollution is a layered issue. Air filters and other technological fixes, though necessary as immediate responses, work at a superficial level. Such measures, often politically convenient and symbolically significant, become ends in themselves because they allow the authorities to show that “something has been done”. This also lulls citizens into believing that action has been taken, allowing the authorities to escape the more difficult, comprehensive and long-term measures that are required.

The present situation calls for a holistic response. In focusing on near-term fixes, the authorities not only avoid their responsibility to evolve a holistic plan but also display their ignorance about the larger ecological framework within which air pollution occurs. The quality of air is invariably and inextricably linked to, or a result of, the quality of ecology in a city. The more green and open areas, the greater the number of trees across a city, and the more complex its biodiversity, the better its air quality will be.

Trees sequester carbon and help to decarbonise the city’s air – they can influence air quality locally, but also over a large area, by changing the deposition and dispersal rates of pollutants in the air. By absorbing toxic pollutants which give high readings of PM 2.5 and PM 10, they help to naturally ‘filter’ the air.

How does Mumbai fare? The city lost more than 2,028 hectares of tree cover – or one and half times the size of Aarey forest – in only five years between 2016 and 2021, according to the Mumbai Climate Action Plan. In Aarey itself, nearly 2,140 trees were felled virtually overnight for the car shed of Mumbai Metro 3. Claims made by authorities of transplanting trees must be taken at face value given that the Bombay High Court’s fact-finding team found in 2019 that more than 60 per cent of the transplanted ones had died.

Similarly with mangroves, which besides preventing erosion and absorbing storm surges, capture massive amounts of carbon emissions from the atmosphere. Spread across Mahim, Bandra, Versova, Vikhroli, Airoli, Vasai, Malad and Manori, and Sewri, Mumbai’s mangroves have served as its ecological sentinels. Between 1991 and 2001, the city lost a large swathe of its mangroves. However, thanks to the sustained campaigns by citizens’ groups and some judicial intervention, the mangrove cover stabilised at around 36 square kilometres in the past few years. The threat is not over – mangrove patches are at risk from infrastructure projects such as the Coastal Road and the Mumbai-Ahmedabad bullet train.

Photo: Maitreyee Rele

Cutting through the smog

The air purifier towers and filters apart, there are steps that authorities can take to make Mumbai’s less polluted and hazardous.

Ecological plan: Mumbai needs a comprehensive, far-reaching, and inclusive plan to address air pollution in a meaningful way. The need of the hour is an Ecological Plan, on the lines of the city’s Development Plan 2034, which can map all its natural areas, chart ecological goals, and decide steps to conserve these areas in ten-year and 20-year periods.

The Ecological Plan must have clear no-go areas where all ‘development’ which threatens ecological balance and diversity is proscribed, set down air and water pollution parameters which cannot be breached (construction activities must not be allowed between November and February when the air quality is ‘very poor’), lay down a roadmap to increase the tree cover. Officials at ward levels must be made accountable for the natural areas in their wards. The Ecological Plan would be more comprehensive than the city’s Climate Action Plan; it must inform the Development Plan.

Immediate response: In the near-term, urgent steps are required such as following Central Pollution Control Board guidelines to mitigate construction dust including sprinkling water, covering sheets on construction material and debris, washing truck tyres and so on; movement of commercial transport can be regulated in the day time to cut down vehicular emissions, and so on.

Monitoring and measuring air quality must be taken to the next level of informing Mumbaikars in a continuous manner on the lines of COVID-19 dashboard. The authorities must also think of Low Emission Zone policies which have yielded good results in international cities.

Multiple agencies: The buck should stop at the BMC, but given Mumbai’s fragmented system of governance institutions, other authorities such as the MPCB, Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority, Mumbai Metro and others are responsible for various actions to keep the pollution levels down. What is needed is a clearer chain of command where irrespective of the agency working on the ground, the BMC must have the mandate to enforce all norms to combat air pollution.

Economy and public health: Continuing high pollution levels, accompanied by other incidences such as high summer heat and urban flooding, can eventually reflect on the city’s economy. Their economic impact must be borne in mind, but for now the BMC’s focus must be on public health; it must involve its own and the government’s health departments in tackling the impact of air pollution on people.

The bad air days will pass, the problem will persist unless holistically addressed.

Smruti Koppikar is a Mumbai-based award-winning journalist, urban chronicler, and media educator. She has more than three decades experience in newsrooms in writing and editing capacities, she focussed on urban issues in the last decade while documenting cities in transition with Mumbai as her focus. She was a member of the group which worked to include gender in Mumbai’s Development Plan 2034 and is the Founder Editor of Question of Cities.

Cover photo: Samarth Das