It is no secret that human intervention has caused the current climate emergency. Scientists have been telling us for decades that the future will be hotter and wetter, with longer periods of drought and more extreme weather events. Climate variability will destroy the predictable seasonal rainfall patterns that farmers rely on to plan their crops. Reduced harvests will contribute to conflict, which will in turn drive migration towards already-congested cities and towns around the world.

One answer to growing cities has historically been the development of New Towns or planned urban areas that are built on greenfield sites. They emerge quickly from detailed planning documents and are capable of housing millions within just a few years, as both China and Egypt have shown.[1] This speed and efficiency lies in contrast to the majority of cities and towns that develop in haphazard stops and starts over centennia according to political wills and financial whims.

At the time of their development, New Towns are often seen as an opportunity to explore fresh ideas, to experiment with new socio-spatial organisations, or to aim for extreme efficiency. For their residents, New Towns can be an exciting alternative to congested cities, inspiring a shared feeling of belonging and pioneering. But New Towns can equally fall into a trap where the prevailing planning dogmas of a single moment in time become crystallised in street patterns, housing typologies, and urban programming that quickly becomes outdated and discredited. What was once bright and shiny becomes old and dull.

This tendency to age all at once means that New Towns require either a strategic long-term maintenance plan, or the occasional city-scale refurbishment. Globally, the construction industry is one of major contributors to both greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and energy consumption. The compounding effects of maintaining, heating, cooling and renovating buildings and infrastructure in New Towns can hardly be overstated.

Climate emergency is also opportunity

However, this rather bleak sketch does not necessitate despair. New Towns in the current climate emergency present us with a challenge, yes, but also an opportunity to take bold steps towards more sustainable, inclusive and democratic city-making.

Since the rise of neoliberal ideologies around the world, New Towns have become an increasingly popular approach from both public and private development bodies, particularly in emerging economies. As these places experience rapid population and economic growth, the demand for large and high-quality housing, green public spaces, educational opportunities, and safety become key concerns. Middle-income groups demand urban amenities that reflect world standards, and increasing car ownership creates an increasing need for parking spaces and wider roads – which in turn drives further demand for private car ownership as places become inaccessible to slower traffic like pedestrians and cyclists.

Photo: Creative Commons

How can we balance these with the well-known consequences of 20th century development approaches? The planning and design principles that inspired a wave of New Towns around the world following WWII are no longer sufficient, or even relevant in some cases. Single family housing solutions, spatial segregation at the neighbourhood scale, and tabula rasa planning approaches must be left in the past.

Unfortunately, the vast majority of contemporary New Towns are still initiated and led by decision-makers with priorities that reflect capitalist ambitions of profit and spatial segregation, driven by false economic arguments of ‘market demand’. We see this again and again, in examples from Brazil to India, from Angola to South Korea. Around the globe ‘development’ is still predominantly interpreted as more buildings, more roads, more cars.

New Towns may be designed to function in one way, but people will inevitably appropriate space and introduce urban uses that the designers could not have imagined. Also, there is the simple fact that the world changes quickly, and the way people want to live changes with it. New Towns often find it difficult to evolve at the same pace as human progress.

Old-approach New Towns

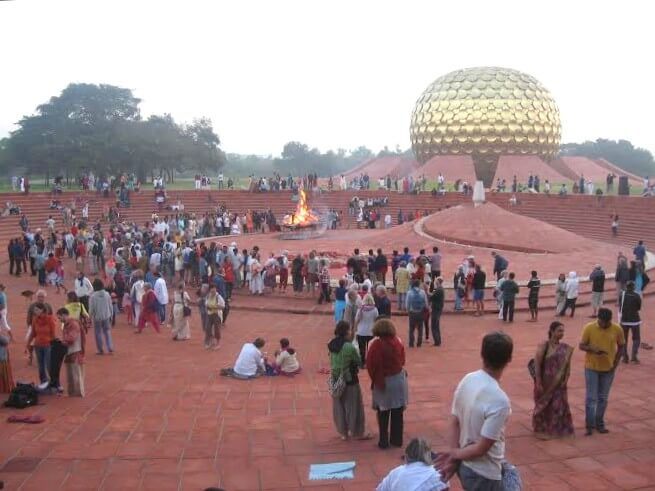

New Towns from the previous century point to the difficulties in employing this development approach. For example, the Universal Township Project of Auroville, India, with its guiding principle of human unity and harmony, celebrates a simple and worthy goal, but has not reached its ambitions in terms of size and scale. It remains a charming and inspiring example, but one that is appealing to idealistic architecture students and seekers rather than a realistic blueprint for housing millions as the planet heats up.

In another famous Indian example, Le Corbusier’s design for Chandigarh was intended to be an archetype for modern India, exhibiting all the values of a young and ambitious democracy. Chandigarh’s failed attempt at equitable access through a grid-iron street plan again shows us how the best design intentions can be reinterpreted to insert social hierarchies where they were never anticipated.[4]

In Tema, Ghana, designed as an industrial port town by Constantinos Doxiadis to facilitate equitable access to affordable housing, urban services, and unlimited expansion over time, we see how financial limitations and top-down decision-making can divert New Towns from their original ambitions. In many cases, New Towns are projects that are left unfinished, creating hybrid urban developments that diverge wildly from the planners’ original intentions.

Abuja, Nigeria was designed to eventually accommodate three million residents and is now home to upwards of six million inhabitants (estimated), and consistently ranks as one of the fastest growing cities in the world. This unstructured growth has led to massive evictions and violent displacements as land disputes become the norm. The ‘predict and provide’ spatial planning approach fell short because planners simply cannot predict the demographic and natural changes that inevitably occur.

In these examples, the main objective was to design a New Town that reflected social and democratic ideals. In the context of the climate emergency, new urgencies arise in addition to existing concerns for social justice and inclusivity. It is no longer enough to consider the needs of people alone, because those needs are now tied up in the future of the world’s ecosystems. They always were, of course, but for a while we were able to convince ourselves that we were somehow entitled to exploit the world’s resources without any repercussions.

Now we know better, and it’s time to see this knowledge reflected in new visions for urban futures: We need rules and regulations that clearly define sustainable development and articulate it in planning law and policies; designs that are conceived around circular building materials and people’s participation in the construction process; sustainable energy sources and water management plans that anticipate extreme weather events; and green and blue networks that combat heat-island effects and support biodiversity and seasonal natural flows.

Photo: Creative Commons

The BuraNEST example

Where can we find examples of New Towns that embrace this new, alternative vision? Although few and far between, there are some which successfully bring together ecological and social concerns. BuraNEST, a New Town in rural Ethiopia, may be one of the most exciting examples of how this approach can work with ecological constraints rather than against them.

The idea for BuraNEST was conceived by a small group of Ethiopian and Swiss architects who were actively engaged with issues of social justice and sustainability. The team understood the challenges of rural life in Ethiopia in general terms, and used this knowledge to look for an appropriate site to situate their experimental New Town. The site for BuraNEST was in some ways typical of rural occupation patterns in Oromia region, with individual houses set far apart from each other and grazing land in between. During the rainy season, some houses became inaccessible when the local river would flood.

After discussions with politicians and decision-makers, the design team went into the community and, in the shade of a flowering tree, they explained their ideas about access to healthcare and education, about homes that could withstand decades of weathering, and about the benefits of living closer together and sharing some resources. After months of talking in groups, talking individually and sharing concerns, the community was on board.

The first action point was to plant a eucalyptus forest. The young eucalyptus trees would grow fast, and could be used to frame the buildings. The forest itself would aid in rainwater absorption and retention, and prevent further erosion along the riverbanks. The green space under the canopy could be used for gatherings or recreation. Excess trees could be used for fuel, or sold for profit. The eucalyptus forest became one of the central components of the New Town, and a prime example of the ripples effects from one small intervention: Want to build a New Town? Plant a forest first.

Ecological New Towns

It is almost always more sustainable to redevelop or densify existing urban fabric, so when the decision is made to transform a greenfield site into a New Town, it is critical that the objectives of that new urban development respond to the uncomfortable realities of the Anthropocene: Sea levels will rise and many coastal towns will face planned relocation; the planet will be warmer, with more frequent extreme weather events; and the poor and most vulnerable populations will continue to suffer more than the wealthy. The ecological and social implications of the climate crisis cannot be untangled from each other.

Photo: Creative Commons

However, against this backdrop, New Towns can help usher us into an urban future that is more sustainable, equitable, and democratic. Although they haven’t yet stepped into this potential, there is a clear imperative to move away from outdated development practices and actively step towards urban development that is not only carbon-neutral but that actively improves rubrics like biodiversity, water management, social justice, and future-proof construction. More weather variability and climate changes will force people with agrarian livelihoods to move to urban areas for employment.[6] More people will migrate to cities and towns, arriving in peripheral areas that offer ‘low cost-high risk’ land. Informal and unregulated settlements will continue to grow.

New Towns offer an opportunity to respond to climate emergency. We can use the development approach to enable holistic integration of people and places, but first we need the dreams, the creativity of designers and storytellers to envision futures that inspire rather than depress. What are the utopian ambitions of this generation? In the current context of neo-liberal and private capital-led urban development, it will take a monumental effort to shift our collective thinking away from short-term profit towards ecologically sustainable and socially equitable city-making. But it can be done, it must be done.

When planning new cities, a number of ecological concerns must be addressed. These concerns change as the planning progresses and according to local contexts, but in general, the first and most critical ecological decision is that of site selection. Where will the new city take form? What underlying blue-green infrastructures can be enhanced or supported through the city-making process? A natural site is never a tabula rasa. Site conditions and elements should be studied carefully and incorporated in the urban design where possible. For example: Is there an existing wildlife corridor? Can that become a green transect that provides natural public green space, cools the city, and preserves biodiversity? Or is there perhaps a water source, lake or river? Will the river flood during certain seasons? How can the urban space be designed to accommodate temporal changes?

Planners have to think of the natural landscape as an opportunity rather than a constraint, thinking across different time and geographic scales. They need the insights of environmental experts and ecologists whose knowledge they must synthesise to design in ways that bring together the needs of humans and the changing flows of natural systems. Ecological concerns such as access to water, prevailing winds, and solar orientation should be addressed in every urban design, and then addressed again at the architectural scale. Designers can create streets that shade and cool pedestrians rather than urban heat islands, but this can only be done when designers and other stakeholders commit to this end goal.

A city does not exist outside of its natural conditions, no matter how much air conditioning or bottled water we use. As Climate Change continues to increase in intensity and variability, we will feel the effects of these decisions all the more.

Dr. ir. Rachel Keeton is an American and Dutch architect, urbanist, and researcher currently working at the University of Twente. Her research is situated at the intersection of climate change, migration, and city-making. This work is largely focused within the African continent and informed by feminism, social justice and environmental intersectionality.

Cover photo: Creative Commons