In discussing green buildings and their place in our world increasingly challenged by the climate change crisis, I want to first acknowledge something innate and fundamental to the subject: The bigger ecological dilemma.

Green buildings are seen as important interventions in the era of the climate crisis. They are, indeed. There is an urgent need for all buildings to go as green as possible, as these brilliant illustrations by QoC illustrator Nikeita Saraf show. Yet, it is important to understand that the human effort to make buildings green comes after ecological destruction of the land that existed before the buildings were constructed.

The ecological destruction is sanctioned and presided over by legally standing policies and decisions of state and city-level planning agencies and their zoning exercises to accommodate the growing demand for built spaces in cities. Land is stripped off its natural ecology, biodiversity, and complex webs of life to make place for the built environment.

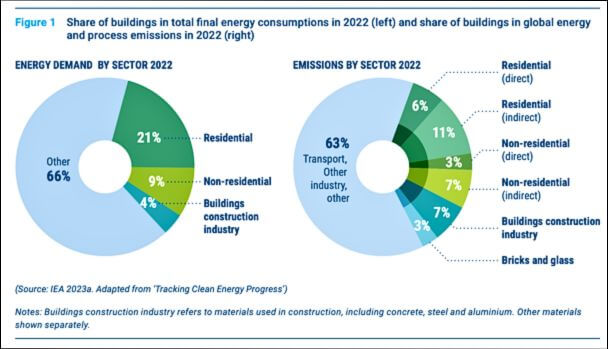

The likelihood of any building that’s constructed on this land bringing back or replicating the ecological richness of what once existed there are exceedingly slim. Not only for a conventional building but a “green” building too, though in different degrees. Green buildings, therefore, must be seen in the larger ecological context and not merely for themselves, isolated from the context. While they are important given the large contribution of the construction industry to the greenhouse gas emissions (as much as 37 percent globally) is, focussing on buildings while ignoring the conservation and regeneration of the natural environment would be a limited effort to address the climate crisis.

Green buildings

The definitions of green building are many and can vary depending on the source one looks up. A broadly accepted one is that, at their core, these buildings cause the least environmental damage during and after construction while maintaining occupant’s comfort.

“Green or sustainable building defines constructing healthier, more energy efficient and eco- friendly buildings. A green building uses less energy, water, and natural resources, creates less waste and is healthier for the people living inside compared to a standard building,” explains GRIHA or Green Rating for Integrated Habitat Assessment, a recognised rating system in India.[1] Essentially, it is about constructing structures that are environmentally responsible.

Green buildings typically use renewable and low-impact materials, try to conserve water and power, use energy-efficient appliances, reduce waste or compost it, make space for green roofs and living walks with ample garden spaces and so on. The green building approach covers its entire life cycle from siting and design to construction and maintenance. As the US Environment Protection Agency notes: “Applying green building practices can help reduce a building’s overall impact on the natural environment by more efficiently using energy, water, and other resources.”

Green building is not as high-tech as it initially sounds. While modern heating, cooling, ventilation, and lighting systems play an important role in making a building more environmentally responsible or “green”, much of what characterises it is deeply rooted in age-old approach to buildings. Older buildings kept the environment in consideration. I can argue that most buildings until the onset of the modern capitalist world were, in fact, green buildings, in sync with local ecology and region.

With the reality of a growing population and urban migration against the backdrop of a ‘growth-driven market psychology’, we have come to normalise mass production of built structures that no longer consider the ecology and region. One where more concrete-and-steel based construction, for the sake of construction, has come to represent ‘development’.

While the technology has vastly improved over time, and the need for greening our buildings has been advocated as a way to address climate challenges, reinforcing the older approaches and thoughtfulness has become more challenging. The modern green building approach is what we have. And this includes the rating system – a way to determine which building is green enough and how to make it greener.

Green building rating systems

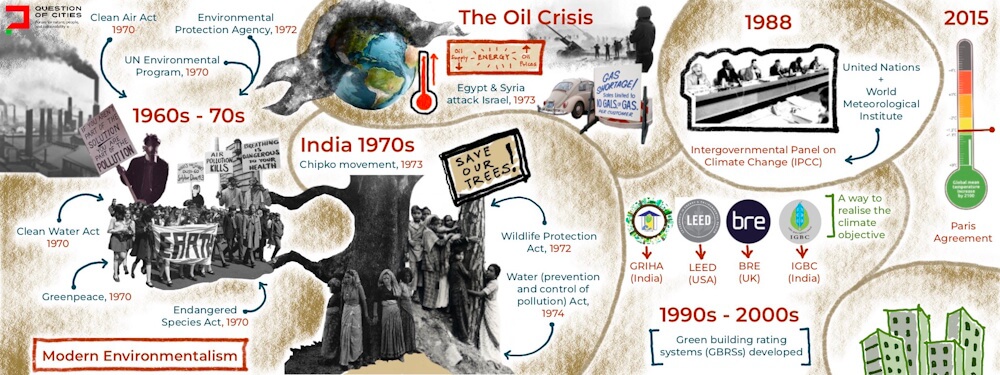

The rating systems are a way to realise the objective. Green Building Rating Systems (GBRS) have been set up in various countries, including in India, as organisations that develop knowledge on green buildings, propagate their acceptance primarily through government partnerships and/or marketplace approaches, and offer a table of ratings that developers and builders can apply for.

The first were set up in the United Kingdom as BRE and in the United States of America as LEED in the early 1990s. The LEED penetrated the Indian market in the early 2000s but India soon developed two national rating systems, the Indian Green Building Council (IGBC) and GRIHA. The early efforts and anecdotes have been captured HERE and HERE by stalwarts like V Suresh and Dr Hariharan Chandrashekar.

These agencies developed performance-based guidelines for the construction industry to transition to everything ‘green’. The guidelines evaluate a building’s “greenness” across categories such as use of materials and energy efficiency, to cite two. They cover aspects beyond the building too such as site planning, construction management, and socio-economic strategies integrated into the design and the construction process.

Within each category or theme, a list of specific measurable expectations is defined. For example, improving the building’s energy or electricity performance by a certain percentage will earn the project a corresponding number of points. Depending on the level of compliance with such specific requirements, the project is given a total score which, in turn, is used to decide the level of certification. The highest is a ‘5 Star’ or ‘Platinum Rating’. The agencies conduct regular audits of a certified project and collect evidence from the design and construction teams to ensure compliance is true.

Current status

In the last two decades or so, India’s rating systems have become more robust and have been relatively successful in popularising the environmental aspect in mainstream design and construction. The number of green buildings certified has grown every year, from less than 25,000 square feet in 2004 to close to 14 billion square feet in 2024.

However, there is a problem that I must state, one that has bothered me since I began interacting with the ratings systems in a professional capacity. While the number has grown over the years, it still makes only a small fraction (just over 5 percent) of the total built-up output in India. It is also worth noting that the adoption is not uniform. Some states like Maharashtra, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu have adopted the green buildings framework and ratings systems more than others, and some building sectors such as office buildings more than residential ones.

The growing-but-low-adoption has compelled the ratings systems to constantly negotiate two priorities: Keeping ‘green’ expectations low to drive wider national penetration versus raising the bar to ensure the country’s building stock aligns with urgent environmental needs.

Over the years, my observation is that the ratings systems prioritise the wider national adoption. There is value here, no doubt. Large number of small green acts can indeed add up for a greater national impact. However, since the expected level of adoption has not happened after two decades, this strategy of popularising green buildings has come at the cost of the higher environmental standards urgently required today, besides risking the systems as a mere tick-box exercise for the construction industry rather than truly driving sustainability.

Enter the climate crisis

My disquiet with this low-adoption of ‘greenness’ in the construction sector has compounded with the ongoing climate crisis and India’s goal to be Net Zero by 2070. This cannot be achieved without a meaningful decarbonisation of the building/construction industry which is responsible for 37 percent of the global energy and process emissions.[2]

This is primarily due to a building’s dependency on electricity-from-grid – which is largely fossil-based – to power it through its long life, dependency on other fossil-based energy for manufacture of building materials, and their transportation. Concrete and steel, two of the most widely used construction materials today, are considered to have ‘hard-to-abate’ emissions. Put another way, the building industry is slated to have large quantities of greenhouse gas emissions.

India, even with its 2070 Net Zero target – 20 years behind the global goal of 2050 – will need to decarbonise the construction industry rapidly. The rating systems have been changing to respond to the times. While maintaining their existing frameworks, they have begun to look at emissions in buildings too, new added criteria have been added to the existing list of what makes a building ‘green’, and altogether new guidelines are being developed for exclusive low carbon building certifications (often called net-zero Buildings).

Achieving meaningful scale in free market

But can the rating systems, which struggle to scale, help with de-carbonisation? We have normalised the slow speed of adoption, which is dangerous. The challenges are manifold – a lack of awareness among stakeholders, absence of widespread expertise, gaps in sustainable building material marketplace, and lingering misconceptions about higher costs, among others.

However, there is another important factor at work here. It could be that the rating systems failed to scale because, even after two decades in India, they have remained a parallel and voluntary free-market model outside of the country’s existing set of laws and regulations on buildings. In fact, the green building movement has completely handed the free market God-like-authority to decide on a case-by-case basis whether it wants to factor in the environmental and climate challenges.

Without a doubt, it raises the systemic question on how reliable a free-market approach can really be for a thriving planet, but that’s for another edition. Should ‘green’ and ‘pro-climate’ not be our default baseline for all design and construction, enforced legally? Just like we did not create parallel voluntary free-market models to ensure our buildings are safe from fires and earthquakes, should we not focus on integrating ‘green’ into local bye-laws?

Another aspect is that beyond the rating systems, India has an evolving National Building Code, first published in 1970, and programmes by the Bureau of Energy Efficiency[3] set up by GoI in 2002 such as Energy Conservation Building Code and, more recently, Energy Conservation & Sustainable Building Code which attempt to mainstream ‘greenness’.

An aspect that flies below the radar is that while these different universes of frameworks progress at their own speeds, their ultimate adaptation and streamlining into action depends on the willingness of the local urban bodies and state governments. This places the burden of operationalising or mandating the green building concept firmly and squarely on urban local bodies.

Way forward

If the end goal is to mainstream environmental considerations into the construction industry, a lot needs to change at the strategical level. The ratings systems, governments, and the construction sector must first come to terms with the learnings of the last 20-plus years.

For the adoption of green buildings at the speed and scale that the climate crisis demands, the following must be acknowledged: The voluntary model is not working, the free-market approach is not working either, and we risk losing time thanks to the multiple or duplicate green building frameworks under different programmes.

We must return to one true system of construction into which the green building approach and framework are integrated. No parallel systems and, definitely, not voluntary. And no God-like power to the free-market to ‘choose’ ecology under market pressure. Going forward, every building must be green, by default.

As I write this, I am aware that the success of such mainstreaming will not happen in a vacuum. It will need a shared vision and commitment, not only between the rating systems and urban local bodies but also from the political structures. They must together find a way to leverage the already existing local bye-laws to meet this end without making it voluntary. In all fairness, the agencies in India, year after year, do engage with local urban bodies to advocate for green buildings rating systems to be integrated into local regulations. While this has shown results in many states, the progress is slow – usually caught up in slow bureaucratic timelines.

Where the bye-laws have the provisions, it remains voluntary. For me, the success story will be when green building expectations merge into the mandatory section of building bye-laws and, then, pave the way for honest implementation just as it is done for building safety. This is not to say, the green building rating systems should cease to exist eventually; instead, they must continue for research and development in making the construction industry greener, as India moves into the most important ecological and climate times.

Harish Borah, a subject expert in climate action and mitigation with 10-plus years of experience, was a QoC-CANSA Fellow 2023. He has been named among the top 25 leading minds in sustainability by The Economic Times, India, and his writing has been tabled at top climate negotiations including at COP28. He was also a part of the ‘2041 Climate Force Antarctica’ crew. Among various engagements, he is the founder of ‘OnePointFive’ collective that focuses on creating a space in India for new climate thinkers to emerge. An alumnus of NIT Silchar, the University of Manchester, and the University of Cambridge, he works as a carbon study/analysis expert for ADW Developments (UK) and serves as a technical advisor to GRIHA and IGBC in India.

Illustrations: Nikeita Saraf