Mithoo Lal, a migrant worker from Madhya Pradesh, lives with his wife and two daughters under a flyover in Munirka, which is located close to Delhi’s posh colony of Vasant Vihar. The family prepares dinner over a temporary wooden fire on a cold evening; the monsoon and resulting floods are equally a challenge here. Near the New Delhi railway station, on the Paharganj side, Shankar stretches out his blanket close to the bus stand and finds his ‘home’ for the night. The migrant worker from Bihar has nowhere else to go. Then, there are drifters who have spent decades residing under one of many flyovers in the national capital — through scorching summers, pouring rain, or biting cold.

Lal, Shankar and hundreds of thousands of homeless people in Delhi who are seen – and dismissed or criticised – under flyovers, on pavements, right outside bus stands and railway stations among other corners and crannies that offer shelter, could seek accommodation at government-run shelter homes or rain baseras. However, they rarely do, preferring instead to struggle through the heat, rain and cold in their makeshift tenements in misery. Therein lies a story of access to housing, temporary or permanent.

Lal, who lives with about nine families like his, all hailing from Chhindwara in Madhya Pradesh, goes back home for a couple of months every year to earn as an agricultural labour, but always returns to his ‘home’ on Delhi’s pavements. “I have been living here for the past 18 years. I don’t even remember when I came to Delhi,” Lal says, adding that most of his relatives are back in Chhindwara, “I don’t have any land there and there isn’t much work. Here, I am able to earn a few bucks by picking up rags and selling them.”

Why does he not shift to a rain basera with his family? “We are people native to MP. Where will we fit in? Moreover, the shelters are often dominated by inebriated men and drug addicts, making it a worrying place for our daughters and wives.”

The absence of comprehensive data on shelter-less people in Delhi is a template example of systemic violence against the marginalised and the collapse of housing policies too. The Census Survey 2011 estimates only around 47,000 homeless people in Delhi but activists claim that the figure is no less than around two lakh individuals at least. The 198 shelter homes, or rain baseras, cater to barely 19,000 people. In July, 2020, Delhi State Legal Services Authority, on directions of Delhi High Court, submitted a report on the conditions of shelter homes which highlighted their below-satisfactory conditions.[1] Those who cannot afford a permanent dwelling with basic minimum amenities are barely able to access and use transit accommodation too.

Homelessness as national crisis

Unlike floods or earthquakes, poverty and its related challenges are seldom counted as disasters, argues Akhil Gupta, professor of Anthropology at University of California, in his book ‘Red Tape: Bureaucracy, Structural Violence, and Poverty in India’. Homelessness, and deaths arising from the sheer stress it places on individuals, have not made the list of disasters nor are they treated as a ‘dire national crisis’.

Homelessness, or the other side of housing, is not a new phenomenon either. From 2001 to 2011, there has been a nearly 36 percent increase in urban homeless households in India.[2] Why is it not classified as a disaster? Do those living on the streets not lose their identity as citizens, and often end up losing their lives too? After years of policies which promise housing and intermediate measures such as rain baseras, people still struggle and suffer their way through lack of adequate shelter.

People may bond over their condition too, as the grey-haired Lakshmi Devi, hailing from Andhra Pradesh and living on the streets in Delhi since 2003, does. “My husband died in 1994 and my son died in an accident in 2001. My daughter is married and in Delhi, but her husband is abusive and doesn’t allow me to live with her. Here, at least it feels like family, with children all around, people to talk to and eat with. Some days, passers-by give us food,” she says.

The homeless look out for one another too. Shambhu, a migrant worker from Sehore in Madhya Pradesh, is among a group residing near a gated colony of Safdarjung Enclave. A rag picker, Shambhu says he earns “Rs 250-Rs 300 on a good day”. His wife Malti cooks for three people every day. Cradling their toddler, she says, “Hum do jaan hai aur wahan ek apahij hai, unke liye bhi banaye hai (we are two of us and then there’s that differently-abled person for whom we cook too).”

The violence of the state

Norwegian sociologist Johan Galtung argues that when individuals or groups are being prevented either directly or indirectly from outliving their potential as human beings, it must be understood as a violation, and violence. Death due to hunger, shelter, and poverty, or due to failure of the state to equitably distribute resources is a violence inflicted on its people. Homelessness, especially during the brutal and cold winters or frightening floods, must be looked at through this lens.

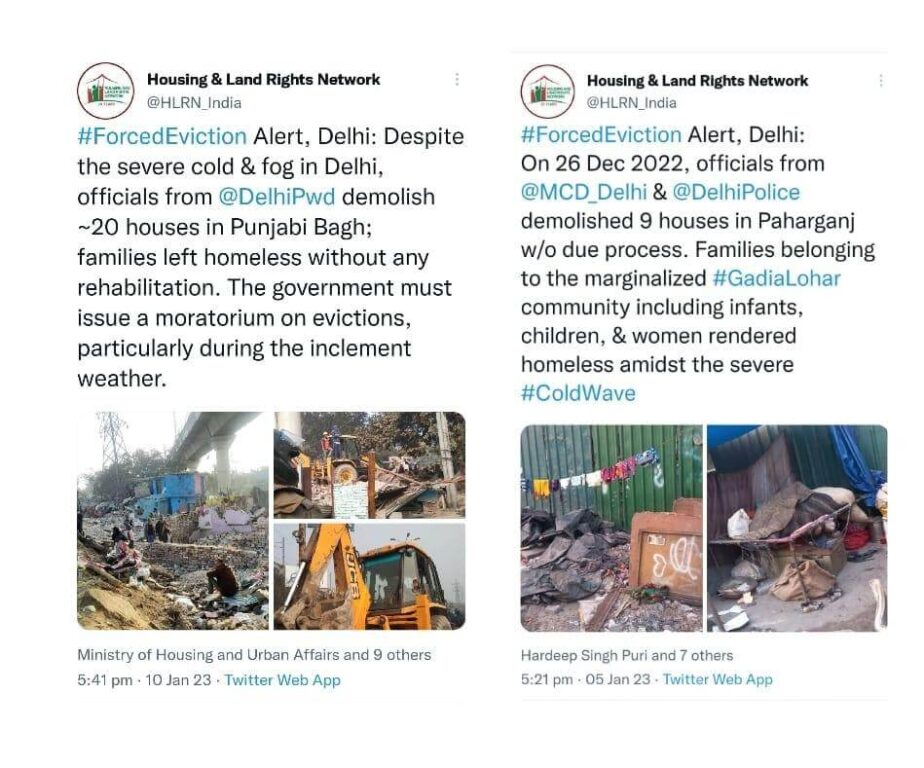

The numbers of homeless swell with every eviction or demolition of what’s popularly called encroachments. According to the ‘Forced Evictions in India-2021’ report[3] published by Housing and Land Rights Network (HRLN), in February 2022, Indian Railways demolished 250 houses to free its land from ‘encroachments’ without any resettlement in the chilling cold; Delhi Public Works Department demolished 20 houses in Punjabi Bagh; and the Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD) along with Delhi Police, on December 26, 2022, demolished nine houses in Paharganj.

The Right to Life and Personal Liberty is enshrined in the Article 21 of the Constitution of India. Any and every act which offends or impairs human dignity constitutes deprivation pro tanto of this right to life. Shelter homes cannot be envisioned as a solution for homelessness, especially, in a city like Delhi but even on this constitutional barometer, shelter homes fall short of their purpose.

Shelter homes, from a number of interviews and ground visits, are inadequate at two levels. One, they are bone-bare with often no bifurcations between beds, they offer only minimal facilities but the conditions in and around the homes are unsanitary, and the space is severely inadequate for families to live. Two, the approach is to not consider social or familial requirements of people or to offer the most marginalised a temporary roof over their heads but, intentionally or otherwise, to dehumanise them as herds. The ‘shelter’ homes are inadequate spaces and dilapidated structures with poor sanitation.

These have come up repeatedly in studies. Sunil Kumar Aledia, executive director at Centre for Holistic Development (CHD), and his team made several visits to shelter homes at Azadpur, Mansarovar, and Old Delhi railway station among others. They found a shortage of beds, congested and unhygienic spaces, and worn-out blankets and mattresses – hardly better than the ‘home’ Lal and Lakshmi Devi have made for themselves. Rain Baseras go unoccupied.

It is ironic but common to find such unoccupied shelters, even in biting cold or rain, near south Delhi streets which were made ‘begging-free zones’ by the Delhi government. At one such shelter in RK Puram, a film plays on an LCD TV but the beds remain unoccupied. Rajpal Singh, managing shelter homes for Society for Promotion of Youth and Masses (SPYM) since 2003, says, “The shelter is seldom full. Some of the inhabitants, however, are regular visitors and have been coming here for the past 2-3 years. I give preference to newcomers, those who are not from Delhi.” SPYM, a Delhi-based NGO, manages more than 65 night shelters built by the Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board.

Aakash, 27-year-old SPYM worker who manages another 20-bed shelter opposite Hyatt Regency hotel at RK Puram, says, “Some days, we have 18 inmates but the number dwindles.” In a city with thousands of homeless, it is bewildering that night shelters do not draw more of the homeless, let alone be overcrowded. Not much seems to have changed since 2015 when Harsh Mander, noted social activist and researcher, observed that homeless people often prefer to sleep on the streets rather than in shelter homes.[4]

Mithoo Lal’s words should make the government review the functioning of night shelters. “The washrooms are very dirty in the rain basera, it’s not safe also. Close to this flyover, we have a Sulabh Sauchalaya (public toilets maintained by the MCD) which is cleaned at 5 am. We bring water from the temporary shelters and women bathe under the flyover.” Shankar too has similar views. Lighting his third cheelam (earthen pipe to smoke) of the night, he says, “The shelter near Gurdwara Bangla Sahib is far for me. It’s also dirty, with lice and bedbugs. The toilets are filthy too. Here, I pay Rs 10 to use the railway station washroom which is clean in the morning, and now they all know me.”

Shambhu points to the safety aspect of the shelters too. “I work till late at night, collecting and scraping garbage. By the time I finish and take my family to a shelter home, I don’t know if there will be space there. If I leave this site, there will be nowhere for us. Also, people in the shelter homes drink and smoke, and my wife doesn’t feel safe.”

Besides the unsanitary and inhospitable conditions, Mander identified another reason that the shelter homes are not preferred by the homeless: The disrespectful and undignified behaviour of the staff posted at these homes. It will take several rounds of sensitisation and training, if at all, for the staff to treat the homeless coming to these shelters with minimum humanity and dignity.

Right to the City: A Dream into Oblivion

Henri Lefebvre’s theoretical concept of the Right to the City, further articulated and put into action by Marxist thinker David Harvey, offers a way to conceptualise citizenship through housing – both the right and access to it in large and unequal cities such as Delhi. ‘Right2City’, an organisation dedicated to furthering the concept, defines it as “the right of all inhabitants, present and future, permanent and temporary, to inhabit, use, occupy, produce, govern and enjoy just, inclusive, safe and sustainable cities, villages and human settlements, defined as commons essential to a full and decent life.”

Even if understood, this does not translate into built spaces and their use. Sunil Kumar Aledia of CHD notes, “Homelessness is a multi-faceted and layered issue and must be treated as one…We can only even dream of the Right to the City when people are treated as citizens of the state. We haven’t even come up with a term that is all-inclusive and encompasses everyone, that’s where we have to start from.”

At every space of the homeless that I stopped to speak, they asked for basic human amenities including money to buy food, woollen clothes and blankets, for their families and profusely blessed on receiving anything. Lakshmi Devi asked me to come with a jacket for her. Mithoo Lal would like “white tents because our blankets get wet by morning due to fog in winters”.

Misnomers like “cold waves deaths” and “flood deaths” are an insult to the lives and deaths of those who build our cities. With adequate and hospitable accommodation, their lives might be secure and comfortable, and they can be as much citizens as anyone else. But the death of homeless people due to inhospitable conditions, which could have been avoided by adequate state response is, to paraphrase Johan Galtung, the failure of the state.

Ayushya Singh works in the field of Development Communication. He has done his M.Phil in urban anthropology from the University of Hyderabad. His areas of interests include critical masculinity studies, and post-colonial urbanism.

All photos by Ayushya Singh.