Dr. Anjali Karol Mohan: ‘We collect vocabularies of people and connect them to climate change’

Well-known planner, faculty, contributor to academic journals, invited member on expert committees, and extensively involved in action research, Dr Mohan’s work lies at the intersection of planning, participation, development, environment and climate change. With degrees in geography and regional planning, and PhD in urban governance and management, her action research across cities in India in Bhopal, Ranchi, Hubballi-Dharwad, Delhi, and Bengaluru, amongst others, is aimed at evolving city-region and neighbourhood scale climate-responsive planning frameworks. Currently, one of her assignments is on exploring methods, processes and approaches to enhance climate literacy, a part of which involves setting up a climate change science and experience glossary.

How climate communication has changed: “About a decade ago, when we started our work, we were not using the term ‘climate change’. As urban planners, we were looking at how to bridge the gap between the planned city envisioned by planners and the lived city which people negotiate on an everyday basis. Notably, urban ecology does not figure in all its dimensions in urban plans. The standardised approach of zoning urban ecologies as ‘open spaces’ often leads to their neglect and fragmentation, leading to a downward spiral in the sustainability cycle. So, we asked how to set the stage for urban ecology in planning and designing a city. Our experience in Ranchi led us to explore the traditional/ indigenous knowledge existing amongst communities about not just foregrounding these ecologies but also stewarding them. This knowledge, we felt, needed to be institutionalised in formal plan and policy and led us to evolve bottom-up planning frameworks.”

“The neglect and fragmentation are largely responsible, amidst other factors, for the changing climates and their manifestation in extreme events. As we continued our exploration in other cities, we realised that when communities experience climate stressors such as floods or experience extreme heat, they are not able to express it. People with access to climate science can comprehend the drivers of these extreme events, the patterns, how they are manifesting on the ground, and how they are impacting the communities. We asked ourselves how to bridge this knowledge between science and experience? That’s when we began to use the lived experiences of people. We worked with our partners to arrive at community-led climate action plans premised on the conninities’ lived everyday experiences. We started to collate these lived experiences, directing conversations with stakeholders. In the process, we started decoding climate science.”

Communicating with people who speak different languages: “I cannot go to the community and use urban terminologies such as ‘urban heat island effect’. Relying on the usual research methods, we encourage communities, more recently expanded to include all income groups, to articulate their experiences. For instance, in Hubballi-Dharwad, we focused on livelihoods. We asked a bamboo weaver about her work in the last couple of years. She expressed a shortage of raw material as bamboo production has gone down ‘because it’s so hot’. Also, the stored bamboo is getting spoiled and it has affected income. Another stakeholder mentioned that when it rained earlier, they felt ‘happy’ and full of joy. Now when it rains, it evokes ‘fear and despair’. These conversations are usually done in the local language, the expressions are a lot richer, to the point and diverse.”

“We have also come across communities who know about the changing climate. Some of them told us that they saw a WhatsApp video of ‘first-time floods’ where people, places and vehicles were inundated. Amidst the middle- and high-income communities, people express that the summer is awful this time and they installed two new ACs in their houses. They know and refer to climate change but they don’t know the meanings of key concepts.”

On the climate glossary: “Our idea has been to understand the lived city through a bottom-up process. We started the glossary for ourselves. We tried to understand key climate concepts. That was the entry point. We knew what climate scientists meant by adaptation, mitigation, urban heat island effect, heat stress, inundation versus flooding (which are two different terminologies) to name a few. We unpacked these terms for ourselves, applied them to the ground to get communities to understand them and explain what they are experiencing, and are now in the process of creating a glossary. In Bhopal, we did it around heat. Heat is not a standalone experience or event; if there is heat, there is drought. If there is drought, there will be flooding soon. Then we created interconnections between different terminologies and events. In Bengaluru, we expanded it to all sorts of climate experiences.”

“The canvas is the city because each city experiences different climate events. So while right now the vocabularies are spatially embedded, we are hoping to evolve a basket of glossaries that are contextually applicable across cities and are different. Contextual relevance is something that we should be cognizant of. The glossary becomes a major resource for people working in this space, including the government and climate scientists, and an important way to communicate climate science concepts.”

Avinash Chanchal: ‘Climate change is professional managerial class language, we need climate dictionaries by the people, for the people’

A climate campaigner involved in climate activism for several years, Chanchal works on various campaigns related to climate change. He leads the campaign team at Greenpeace South Asia. For the last few years, Chanchal has been actively advocating for just and equitable cities. He has led and contributed to public transport and clean air campaigns in various cities and works closely with communities, researchers, and policymakers to advocate for inclusive, sustainable solutions that empower the most affected and marginalised.

What climate communication is: “We do not say ‘climate change’ in the communities we work with. Instead, we incorporate issues which have an intersectionality in their daily lives, social and economic issues. For example, for a campaign on heat waves, we talked to people about their livelihood, how the changing weather patterns impacted work, housing, culture and so on. We make sure that the issues are relatable and personal to them.”

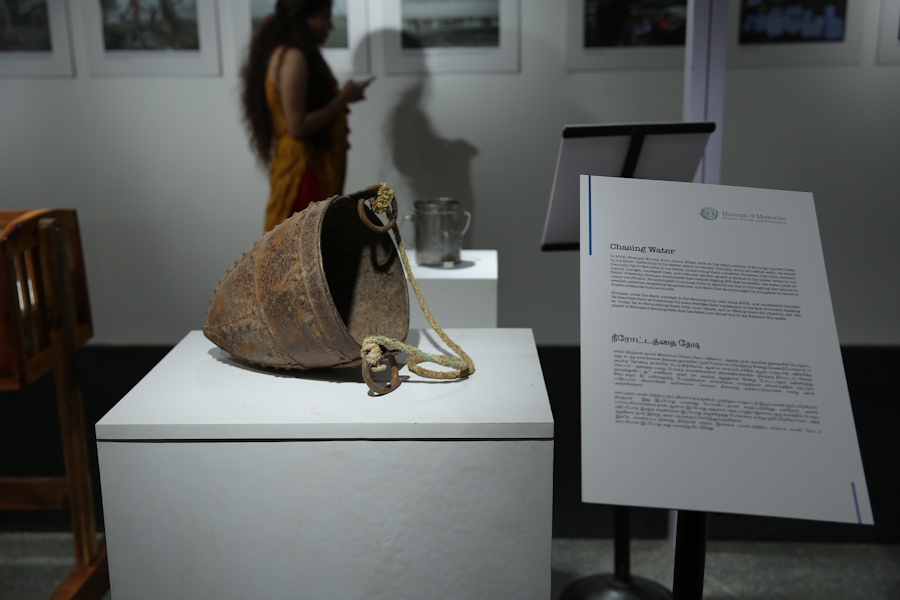

“The second approach is more storytelling than just using data. As climate researchers or practitioners, we often talk about climate change in numbers or technical jargon like loss and damage fund, climate finance, carbon emissions, productivity loss and so on. We quantify it all, including the deaths. I realised that all this becomes dry for people and we started using a lot of storytelling in our campaigns. For example, instead of ‘loss and damage’ in climate finance, we collected personal things of people such as a broken school bag from the Sundarbans, a wedding photo from Chennai, damaged during cyclones or floods, and created a museum out of them—Museum of Memories. This really moved people. I could see they connected. Then, it became easier to talk about loss and damage, funding climate adaptation, and holding polluters accountable.”

Changes in climate communication: “The one thing to acknowledge is, I’m not saying good or bad, that the term ‘climate change’ was given by experts; it’s up to us how to translate it. The scientists, policy experts, and universities started studying climate change. This, in traditional Marxist language, is the professional manager class and this beginning of the climate change discourse had an impact on the language we all use. Many terms come from that background.”

“But the everyday aspects are the extreme weather events and their impacts on people’s lives. So, it’s not some distant reality. There are examples and stories that give it a personal connection, a face. I have seen a lot of changes in climate communication in the last five-seven years. Now it is not done by just the professional managerial class but also by journalists, social media influencers, and content creators who tell stories. Young people and activists have become climate storytellers, writing poems and doing plays on climate change.”

Photo: Avinash Chanchal

Terms versus experiences: “In technical climate terms, if the temperature crosses 42 degrees Celsius, then it is notified as a heat wave. However, at 30-35 degrees people may feel its fatal impacts. Here, the technicality ignores vulnerability. People experience the same temperature unequally based on their different health, social, or economic conditions. Even at 30-32 degrees Celsius, a large number of people feel the harsh impact but for technical or climate science persons, it is not a heat wave. We definitely cannot have one universal word, understanding, or policy. We need more descriptiveness to accommodate diversity, inequality, and multiple languages that India has.”

“In the Hindi-speaking belt, Bangla-speaking belt, Marathi-speaking belt, or even within each of them, there are local climate terms. Is it not important for climate communicators and policymakers to acknowledge and incorporate these? There are not only climate-related words but also songs in Bhojpuri, Bengali, Kumaoni, Marathi, Tamil. A group in Tamil Nadu called Poovulagin Nanbargal translates English books and reports into Tamil; I believe these are best-sellers in book fairs. So, clearly the need and interest is there. The efforts have been led by the citizens’ groups but we need more and different kinds of involvement. Perhaps, regional language writers can give us more words of climate change, how it is understood in their languages. We need language scientists on board too.”

The importance of a climate dictionary: “For me, the question is who is making or writing this dictionary. If it’s the same experts, scientists, researchers, people with degrees in climate science, what’s the point? We need to have a dictionary prepared by communities — by the community, for the community -– because communities already have their local vocabulary. We have to come up with a participatory approach to make the dictionaries so that local words are in it. In that sense, despite the efforts, I don’t see one being written or done by communities, and not by experts.”

Daniel Potter: ‘A huge amount of climate terminology is arcane, risks alienating people who aren’t experts’

The Lead Climate Writer of Terra.do[1], Daniel Potter, reflects on the insights gained at the organisation from educating cohorts since 2020 for climate action. Terra.do has a flagship program called Climate Change: Learning for Action[2] along with other online courses and intensive programmes on a range of themes such as Software for Climate[3], Corporate Sustainability Leadership Accelerator[4], Carbon Accounting and Reduction[5], Mastering Corporate Climate Reporting[6], Digital Product Decarbonisation[7], and Sustainable AI[8] that seek to decode and unpack climate information, climate science, for people.

Climate communication: “Broadly, more people recognise the significance of climate change than say 10-20 years ago. The research from Yale[9] shows that more people in the United States are ‘alarmed’. A paper in Nature[10] surveying 1,30,000 people from 125 countries found that 86 percent endorse pro-climate social norms and 89 percent demand intensified political action. One thing this means for people like us is that we do not have to spend time making a case to do something about climate change; the question is what to do. The best answers vary from one individual to the next.”

“A watershed moment in our class on climate communication came after Katharine Hayhoe’s book Saving Us was published. Conversations about climate communication can veer off into the weeds, on theories of how people receive information, whether that’s enough to compel action. Hayhoe takes a different, more practical, approach that centres human connection. This resonated with us and we retooled the class in 2022; Hayhoe became a central character. We are constantly reviewing and updating our content. A series we are rolling out now reflects how some classes feel different from when we started. The first post in that series is here.”

Photo: Terra.do

Terms and terminologies: “A huge amount of climate terminology is arcane. It risks alienating people who aren’t already dedicated experts. We’re constantly tuning our content based on feedback to make it accessible to the lay audience. But we don’t want to oversimplify it because, after 12 weeks, we want our graduating fellows to feel conversational in climate science and action. Folks often use key terms interchangeably, like global warming and global heating, or climate change and climate crisis.”

“We, at Terra.do, are not big on prescriptions of what terms to use; throughout our course, we strive to introduce experts from around the world, citing their work and quoting it in their own words. In some cases, we introduce a term and say ‘you might see experts use this, let’s unpack its meaning’. An example is Global North and Global South. These speak to the divide between the rich, industrialised nations responsible for most historic climate emissions, and the poorer countries that face disproportionate impacts of it. We think it is unintuitive to say India is part of the Global South and Australia is in the Global North.”

Climate dictionary: “We have not put together one yet but we think it would be a fun project.”

Cover photo: Firasat Mulla