Atif Manzoor, 45, the owner of the renowned blue pottery business in Multan, had every reason to feel cheerful last week when the sun finally came out. For a good three weeks, the city of Sufi shrines had been shrouded in an envelope of thick smog. For over three weeks, he said, business had been terrible, with “several orders cancelled” and advance payments refunded. He also had to bear the transport costs that he had already paid after the government imposed restrictions on heavy traffic and closed the motorways due to poor visibility.

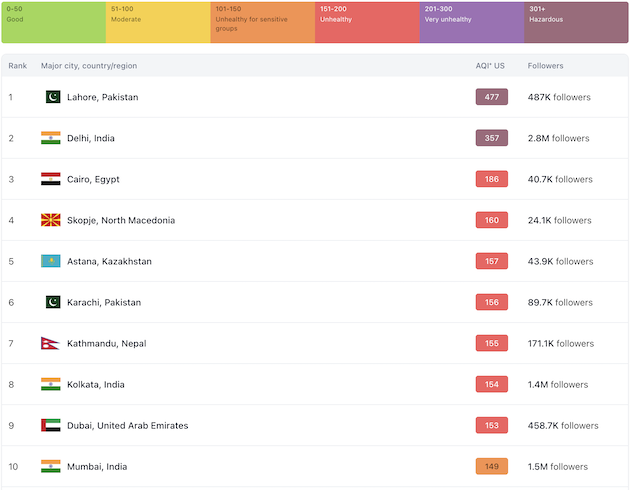

Thick smog had blanketed cities across Punjab province, Pakistan, home to 127 million people, since the last week of October. Multan, with a population of 2.2 million, recorded an air quality index (AQI) above 2,000, surpassing Lahore, the provincial capital, where the AQI exceeded 1,000. The AQI measures the level of fine particles (PM2.5), larger particles (PM10), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), and ozone (O3) in the air. An AQI of 151 to 200 is classified as unhealthy, 201 to 300 very unhealthy, and more than 300 as hazardous.[1]

“It was horrible; I was sick on and off,” said 29-year-old asthmatic Natasha Sohail, who teaches A-Level students at three private schools in Lahore. Early November, her condition worsened with a vertigo attack and fever. “It’s criminal what is happening here,” said an incensed Sohail, referring to the “band-aid measures” taken by the Punjab government. For the past eight years, since Sohail was in college and smog became an annual phenomenon, she has relied on anti-wheezing drugs and inhalers. At home, four air purifiers have helped her breathe cleaner air.

She was not alone. “The hospitals were crowded with tens of thousands of patients suffering from respiratory and heart diseases being treated at hospitals and clinics over the last few weeks,” said Dr Ashraf Nizami, president of the Pakistan Medical Association’s Lahore chapter in November.[2] “The psychological toll the poor air is taking on people remains under the radar.” Punjab’s senior minister, Marriyum Aurangzeb informed journalists that Lahore endured 275 days of unhealthy AQI levels over the past year, with temperatures rising by 2.3 degrees. Authorities closed all primary and secondary schools.[3]

While Lahore’s AQI improved later in November, it still fluctuated between 250 (very unhealthy) and 350 (hazardous) on the Swiss company’s scale, keeping it among the top cities in the world with the poorest air quality. At the end of November, it was 477 (very unhealthy).[4] Terming the AQI levels across Punjab, in particular Lahore and Multan, “unprecedented”, Punjab’s Environment Secretary, Raja Jahangir Anwar, blamed the “lax construction regulations, poor fuel quality, and allowing old smoke-emitting vehicles plying on the roads, residue burning of rice crops to prepare the fields for wheat sowing” as factors contributing to the smog in winter.

Businessman Manzoor was not alone in his predicament. Smog had disrupted everyone’s life in the province, including students, office workers, and those who owned or worked in or owned smoke-emitting businesses like kilns, restaurants, construction, factories, or transport, after authorities put restrictions on them.

Even farmers in rural settings were not spared. Hasan Khan, 60, a farmer from Kasur, said that the lack of sunlight, poor air quality, transport delays preventing labourers from reaching farms, and low visibility were all hindering farm work and stunting crop growth. “The smog hampered plant growth by blocking sunlight and slowing photosynthesis, and since we do flood irrigation, the fields stay drenched longer, causing crop stress, and the trees began shedding their leaves due to poor air quality,” he said.

Credit: IQAir

Climate diplomacy

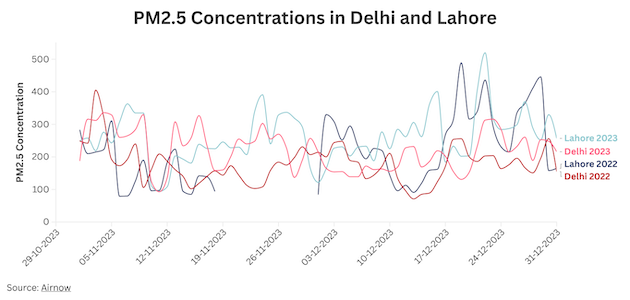

While 70 percent of smog in Lahore is locally generated, nearly 30 percent comes from India, say sources. Manoj Kumar, a scientist with the Finnish Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air, noted that the Indo-Gangetic Plain formed an “interconnected airshed,” affecting air quality but local sources played a major role in Lahore’s pollution levels.

The Punjab chief minister was keen to start talks with her Indian counterpart. “Maryam Nawaz was to send a letter to the Chief Minister of Indian Punjab, expressing her willingness to visit India and invite him to Pakistan,” said Anwar. Kumar praised the Punjab chief minister’s initiative, emphasising that long-term, coordinated efforts between both countries could lead to improved air quality through a unified approach.

But the efforts should not stop at the two Punjab regions alone as the airshed is shared and goes beyond India. Anwar said Pakistan was considering hosting a “regional climate conference in Lahore soon”.

Divine intervention or cloud seeding

After weeks of relentless smog, residents of Punjab had been calling for artificial rain, similar to what was done last year. This process involves releasing chemicals like silver iodide from airplanes to induce rainfall. However, Anwar explained that artificial rain requires specific weather conditions, including the right humidity levels, cloud formations, and wind patterns. “We only carry out cloud seeding when there is at least a 50 percent chance of precipitation,” he said.

On November 15, favorable weather conditions allowed for cloud seeding over several cities and towns in Punjab’s Potohar Plateau, leading to natural rainfall in Islamabad and surrounding areas.[5] The forecast also predicted that this would trigger rain in Lahore. On November 23, Lahore received its first winter rain, which helped clear the thick, toxic smog revealing the sun and a clear blue sky. However, some believe the downpour was the result of the collective rain prayer, Namaz-e-Istisqa, held at mosques across the province, seeking divine intervention.[6]

Cloud seeding has its critics. Dr Ghulam Rasul, advisor at the China-Pakistan Joint Research Centre and former head of the Pakistan Meteorological Department, cautioned that cloud seeding might reduce smog temporarily, but it was not a sustainable solution. Instead, it could create dry conditions that worsen fog and smog. He also warned that an overdose could trigger hail storms or heavy rainfall.

Once the smog thinned and the air quality improved, the government eased its restrictions, allowing shops and restaurants (with barbecues if smoke is controlled) to remain open till 8pm and 10pm respectively; schools and colleges reopened, and the ban placed on construction work, brick kiln operations, and heavy transport vehicles (carrying passengers, fuels, medicines, and foods), including ambulances, rescue, fire brigades, prison, and police vehicles, was lifted.[7] In addition, the government installed 30 air quality monitors around Lahore and other cities of the province.[8]

Health issues linger

While the air may have cleared, health issues left in its wake are expected to persist, according to medical practitioners. Over the past few weeks, the official score of people seeking medical treatment for respiratory problems in the smog-affected districts of the province reached over 1.8 million people.[9] In Lahore, the state-owned news agency, the Associated Press of Pakistan, reported 5,000 cases of asthma.[10]

“Frankly, this figure seems rather underreported,” said Dr Ashraf Nizami, president of the Pakistan Medical Association’s Lahore chapter. “This is just the beginning,” warned Dr Salman Kazmi, an internist in Lahore, “Expect more cases of respiratory infections and heart diseases ahead.”

UNICEF had also warned that 1.1 million children under five years of age in the province were at risk due to air pollution.[11] “Young children are more vulnerable because of smaller lungs, weaker immunity, and faster breathing,” the agency stated.

Credit: Hasan Khan

Government measures at peak pollution

When the AQI in Lahore turned hazardous in November, the government introduced several measures to reduce emissions, adopting a whole-of-government approach with all departments working together for the first time.

Authorities banned motorised rickshaws and barbecuing without filters, distributed 1,000 subsidised super-seeders to farmers as an alternative to burning rice stubble and took legal action against over 400 farmers who violated the burning ban. Penalising a few farmers was meant to deter others from breaking the law. “But the government’s own figures show agriculture contributes less than 4 percent to smog,” pointed out Hassan Khan, a farmer in Punjab, “Why waste so much time and expense on it; why not focus on the bigger polluters like the transport industry?”

Another measure was the government demolishing over 600 of the 11,000 smoke-emitting brick kilns that had not switched to zigzag technology, including 200 in and around Lahore. Terming brick kilns the “low hanging fruit,” Dr Parvez Hassan, senior advocate of the Supreme Court of Pakistan and president of the Pakistan Environmental Law Association, appointed as the chairperson of the Lahore Clean Air Commission and the Smog Commission in 2003 and 2018, did not approve the “arbitrary decision of dismantling” of the kilns.

Anwar said that action also involved visits to 15,000 industrial units, sealing 64 mills and demolishing 152 factories. With 43 percent of air pollution in the province caused by unfit vehicles, Anwar also held the transporters responsible for the smog. He shared that Lahore has 1.3 million cars and 4.5 million two-wheelers, with 1,800 motorcycles added daily.

Band-aid solutions ineffective

Although the government took these measures, few were impressed. Climate governance expert Imran Khalid, blaming the “environmental misgovernance for degradation of an already poor air quality across Pakistan,” found the anti-smog plan a “hodgepodge of general policy measures” with no long-term measurable plan.[12] He argued that the plan only targets seasonal smog instead of taking a year-round “regional, collective approach” to fighting air pollution across the entire Indus-Gangetic plains, not just in Lahore or Multan.

“I will take this seriously when I see a complete action plan in one place, preceded by a diagnostic of the causes and followed by a prioritization of actions with a timeline for implementation monitored by a committee with representation of civil society,” said Dr Anjum Altaf, an educationist specialising in several fields along with environmental sciences. “Until such time, it is just words,” he added.

Khalid said plans and policies can only succeed if they are evidence-based, inclusive, bottom-up, and “and implemented by well-trained authorities, supported by political will and resources, flexible in response to challenges, and focused on the health of the people.”

Others argue that the slow response to the decade-long smog crisis, despite a clear understanding of its causes, reflects a matter of misplaced priorities. “It’s all about priority,” said Aarish Sardar, a design educator, curator, and writer based in Lahore. “Many years ago, when the government wanted to nip the dengue epidemic, it was able to,” he said. “Mosquitoes were eliminated once they reached officials’ residences,” said farmer Khan, agreeing that when there is political will, remarkable changes can occur.

Zofeen Ebrahim is an independent journalist who has written extensively on development issues including Climate Change, urban infrastructure, water, energy, gender, and how these impact our lives. She contributes regularly to English daily, Dawn, The Guardian, The Third Pole, Thomson Reuters Foundation, and Index on Censorship. She was a QoC-CANSA Fellow 2023-24 and her stories in Question of Cities can be found here.

This essay was originally published in the Inter Press Service and has been reproduced here with permission.

Cover Photo: Lahore’s clear blue sky in September and smog-filled sky in November 2024.

Photo courtesy: Zaeema Naeem