The old images of Calcutta, now Kolkata, are not without the hand-pulled rickshaws on its narrow quaint lanes, and the trundling trams sharing space with buses and cars. Even as the city developed, it retained the old modes of transport though the trams and rickshaws have seen a dip in demand because of cars, motorised two-wheelers and the metro. Kolkata has, perhaps, the most complex set of transport systems in an Indian city: ferries, trams, buses, trains, taxis, autorickshaws, cycle rickshaws and metro.

With around 45.3 lakh vehicles for 1,850 kilometres of the city’s total road space, Kolkata’s nearly 14 million people seem to have many transport options to choose from. The share of people walking, cycling and using public transport in Kolkata, according to the Census 2011, was 89 percent— the highest among all metro cities in the country, according to a report by Centre for Science and Environment, Reducing Footprints: A Guidance Framework For Clean And Low Carbon Transport In Kolkata.

This has gradually reduced to about 60 percent using public transit modes, according to this report[1] but the city scores higher than most cities on the usage, affordability and safety of its public transport systems. Besides, a section of residents believe that the public transport network has improved in the last few years.

To increase the modal share of public transport in Kolkata and Howrah, the state government requested IIT-Kharagpur in 2018 to study what should be the ideal number of public vehicles plying on roads every day so that commuters have a hassle-free travelling experience.[2]

Kolkata has had narrow roads and languid traffic interspersed by trams. One of the oldest cities of India, its development was mostly on the western side; the Hooghly river flows along its east. As the city expanded and traffic grew, the roads became congested. Before the pandemic, the annual average increase in vehicle registration in the city was around 4.5 percent which increased to 6.14 percent in 2022 with 21,08,718 vehicles registered. It was an 18.52 percent jump from registrations in 2019, according to West Bengal transport department data.[3]

What added to, and ultimately led to the stress on the transport system, are two factors: The increasing number of vehicles and the indiscriminate parking of vehicles on both sides of the road, says MN Sreehari, government advisor for traffic transport infrastructure.

However, Kolkata’s much-criticised public transport system got an elaborate mention in the third instalment of the sixth assessment report by the Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change (IPCC). The most significant report on the global climate crisis referred to the city’s public transport network as an “illustrative case study” to showcase integrated climate action. Actions on public transport modes have “contributed positively in bringing down the trend of greenhouse gas emissions per unit of gross domestic product to half in one decade” within the Kolkata Metropolitan Area, the report stated. There is “potential for further reduction”, the report added.[4]

Compared to other metropolitan cities, Kolkata is known to be safe for women commuters. Last year in August, the Kolkata transport department started installing panic buttons on state buses. especially for women to use if the need arises.

Metro eases congestion

The city was the first major city in India to get an underground metro network in 1984 as transport authorities believed this was the way forward to solve the then ever-increasing traffic problems arising out of a huge population and crammed roads. The metro, once a novelty, is now part of Kolkata’s fabric, a vital part of the city’s transport network, with around 300 daily train trips carrying more than 7 lakh passengers.[5]

The first stretch in October 1984 was for a distance of 3.4 kms with five stations between Esplanade and Netaji Bhavan. At that point, the city’s population was around 9.8 million; it is now estimated to be 14-15 million. The metro system aimed to alleviate traffic congestion, reduce travel time, and improve the overall quality of life – and found instant popularity among commuters. It was designed to provide a safer and more comfortable commute compared to the overcrowded buses and open trams. Bus tickets at the time were around 40-45 paise while the metro fare was Rs 6.25 paise.

Over the years, expansions and modernisations have enhanced its efficiency and capacity with around 45 trains of 6-8 coaches each plying on the network. However, challenges such as overcrowding during peak hours and maintenance issues persist, highlighting the necessity for continual investment and innovation to meet the city’s evolving transportation demands.

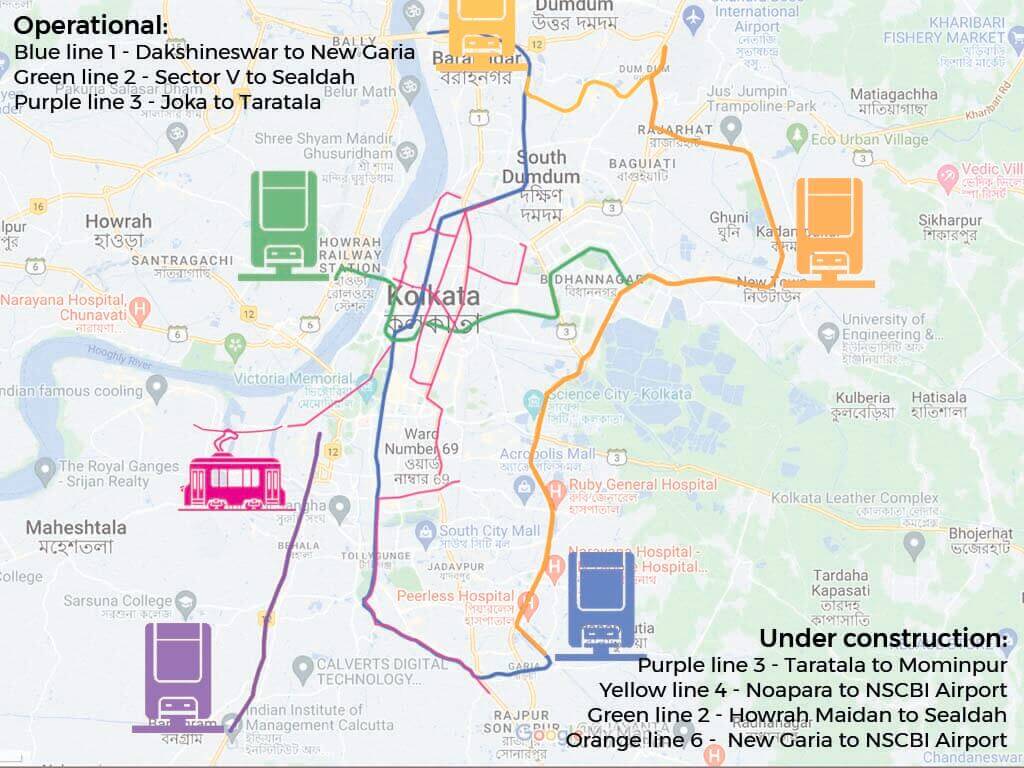

As a frequent traveller on the Kolkata Metro, 32-year-old Atrayee Sen finds it convenient due to its extensive reach and affordability. It is usually punctual and the frequency during peak hours helps though the compartments can get uncomfortably crowded then. Though efficient, the metro could be built only on a few corridors because of space and fund constraints. The corridors covered include the North-South Corridor (26 stations from Dakshineswar to Kavi Subhash), East-West Corridor (8 stations from Salt Lake Sector V to Phoolbagan) and Joka-Esplanade Corridor (6 stations). To this extent, its modal share in carrying the number of passengers is limited.

However, along with trams, the metro is a pollution-free transport option for a city which reels under heavy pollution. This is important because transport-related emissions, especially of diesel-run commercial vehicles, are the main cause of air pollution. Poorly maintained taxis, autos and buses add to the pollution load. The large number of personal vehicles – in 2021, there were nearly 6.5 lakh private cars – causes traffic congestion, fuel burning, and longer commuting time. The metro can be the saviour.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Why buses are important to the city

In 2009, in a move to curb pollution, the Supreme Court had ordered the phasing out of buses older than 15 years. This will remove 4,000 buses from the fleet this year. It might benefit the environment but will add to commuters’ woes as the government does not seem ready to replace them. In fact, the registration of new buses has seen a steady decline from 871 in 2014-15 to only 46 in 2023. The main reason is that the bus service is no longer a lucrative business as bus fares have not been increased in the state for 10 years while prices of diesel and spare parts, cost of insurance, and road tax have increased.

Bus registrations dipped during the pandemic as private bus operators could not purchase new vehicles but the number of taxis and auto-rickshaws went up. In 2021, the city had 16,367 buses compared with 46,528 auto rickshaws and 34,803 taxis.[6]

Arpita Guhathakurta, 46, a regular bus commuter from Baishnabghata, Garia, in south Kolkata, says buses were available with a 10-minute frequency before the pandemic which stretched to 20-25 minutes after it. The private bus fares have risen by Rs 3 to Rs 5 per slab; the minimum fare was raised from Rs 5 to Rs 10 while the government bus fare continues at Rs 8. For a city grappling with road congestion and transport-related air pollution, it is imperative to restrict the number of vehicles and public transport plays a big part in it, says M N Sreehari. “About 15-20 cars are equal to one bus and 20 buses is equal to one metro. Hence, public transport efficiency is critical.” However, the opposite is happening.

Figures released by the state transport department and Kolkata Police show that the city has the highest vehicular density among all Indian metros, with 2,448 vehicles per kilometre of road. Kolkata has approximately 45.3 lakh vehicles plying on 1,850 km of road space, compared to nearly 13 million in Delhi on 33,198 kms of roads — a vehicular density of fewer than 400 per kilometre. Kolkata has 6.5 lakh two-wheelers and 10.7 lakh four-wheelers registered within its limits.[7]

A study in 2021 by a citizens’ group, SwitchON, found that the car count at eight major intersections had jumped up from 17,976 in 2013 to 53,930 in 2020-21. During the same period, the number of scooters and motorcycles increased from 8,689 to 66,038. Together, the congestion reduced the average traffic speed from 24-25 kmph in 2013 to 18-19 kmph in 2020-21. Private cars, along with taxis, accounted for nearly 43 percent of the city’s vehicles while motorcycles and cycles made up a further 23 percent. Only a third of the vehicles comprised public transport: buses, autos and trams. The number of private vehicles have increased manifold after the pandemic as people avoided public transport.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The good old tram

Kolkata is the only city in India to still run a tram service. Once the main mode of travel, it is now of heritage value. After an experimental start on February 24, 1873, when the first horse-drawn tram car ran between Sealdah and Armenian Ghat in north Kolkata, trams were formally introduced in 1880. Electric trams have been operating since 1902.

From around a total track length of 70.74 kms in 1969, trams now run only on three routes: Gariahat to Esplanade, Tollygunge to Ballygunge, and Esplanade to Shyambazar making a total of around 8 kms. They find a place in Rabindranath Tagore’s poem: “Rasta cholechhe jato ajagar shaap/Pithe tar tramgari pore dhup dhap (The roads snaked like pythons/ The tramcars fell hard upon them).” The tram seemed to go well with the pulse of residents here – and are loved.

The government is planning to phase out trams as they are no longer economically feasible and run them for recreation or tourism at a time when the eco-friendly trams are being revived in cities such as Lisbon, Dublin and Berlin. The Calcutta Tram Users Association lists its many advantages: Higher capacity, studier than buses, safe, and environment-friendly. [8]

Somnath Dasgupta, 60, former resident editor of Financial Express, and a regular tram commuter, lauds the slow-paced trams. “Years ago, trams operated on grass strips on the centre of roads in Rash Behari Avenue/Gariahat Road or along the roads like Diamond Harbour Road from Majerhat to Kidderpore. It was easy to board it and get off, without the fear of being run over by a bus or car. Trams were safe for school children travelling alone.”

Later, the government removed the grass strips and made tram lines a part of the road, but in the middle, because tracks along the pavement would affect the space for car parking and hawking. This forced tram users to wait on the roadside and dodge traffic to board one. A frequent complaint is that trams block road traffic but Dasgupta says, “It is the other way round. Cars are using tram spaces for parking. Fines for blocking tram tracks in Australia are so high that no one dares to do it.”

Ferries decongest roads

The cash-strapped ferry services need to be upgraded and improved.

Photo: Wikimedia CommonsKolkata is all set to begin India’s first underwater metro train – part of Kolkata Metro’s East-West corridor – which will allow commuters to travel across the river Hooghly which separates West Bengal’s capital from Howrah, which is known for the largest and busiest railway station. Commuting on and along the river has been part of the city. Almost two lakh people cross the river on diesel-run boats on a weekday, a lakh on a non-working day. But plagued by neglect and scarcity of funds, the Howrah ferry service is barely afloat.

The Hooghly Nadi Jalapath Paribhan Samabai Samity, which runs the ferry service between Howrah and Kolkata, says 13 of their ferries to places like Chandpal, Armenian Ghat, Sovabazar, Baghbazar and Ramkrishnapur-Babughat routes, are in need of urgent repairs. Though the government introduced smart cards at three ghats which helped increase the revenue, more is needed to be done. Once fully implemented, the smart cards will make travel seamless between ferries, buses and metro.

The poor last-mile connectivity in Kolkata is addressed by auto-rickshaws or cycle rickshaws. Dasgupta says the last-mile connectivity is chaotic. Long queues for autos at office hubs like Salt Lake Sector V and New Town are an everyday affair. The approach to solving Kolkata’s traffic woes is to encourage public transport like buses and build proper parking spaces. The government should work out a parking policy and penalise offenders proactively.

“Kolkata was designed as a city based on pedestrian movement and mass transit system in the form of the tram. Cycle rickshaws and hand-pulled rickshaws supported the need of the city considering the narrow streets and the required manoeuvrability.” (IDFC & SGIS, 2008, p. 55)[9]

Urban development has meant that the City of Joy has accommodated new forms of transport, especially private vehicles, leading to more pollution. Kolkata’s future is in going back to its past – to the iconic trams and dependable buses.

Lavina has over 15 years of experience in journalism, research and editing. Living in Kolkata for 38 years, she has seen the city grow and expand. She loves exploring the city’s lanes and bylanes and is awed by its charm and pieces of history it has preserved so well.

Cover photo: Wikimedia Commons