Punjab made it mandatory, last year, for all authorities who own and operate roads to provide pavements and cycle tracks, to address the rising incidence of road deaths among pedestrians and cyclists. This was news but it would not have been if pavements were given due importance in road planning. The government’s move, which it loftily labelled as people’s ‘right to walk’, came only after court orders on Public Interest Litigations which means people fought for pavements.

In a nutshell, this is the story of pavements, or footpaths as they are also called, in cities across India. It is a narrative of official failure to craft thoughtful policies, hubris in making roads without pavements, carelessness or corruption in constructing them, and disregarding people’s accessibility to pavements for their needs or as their right. Pavements, where provided, are usually left-over or residual spaces after planning and constructing the road. They are hardly planned spaces, keeping people at the centre.

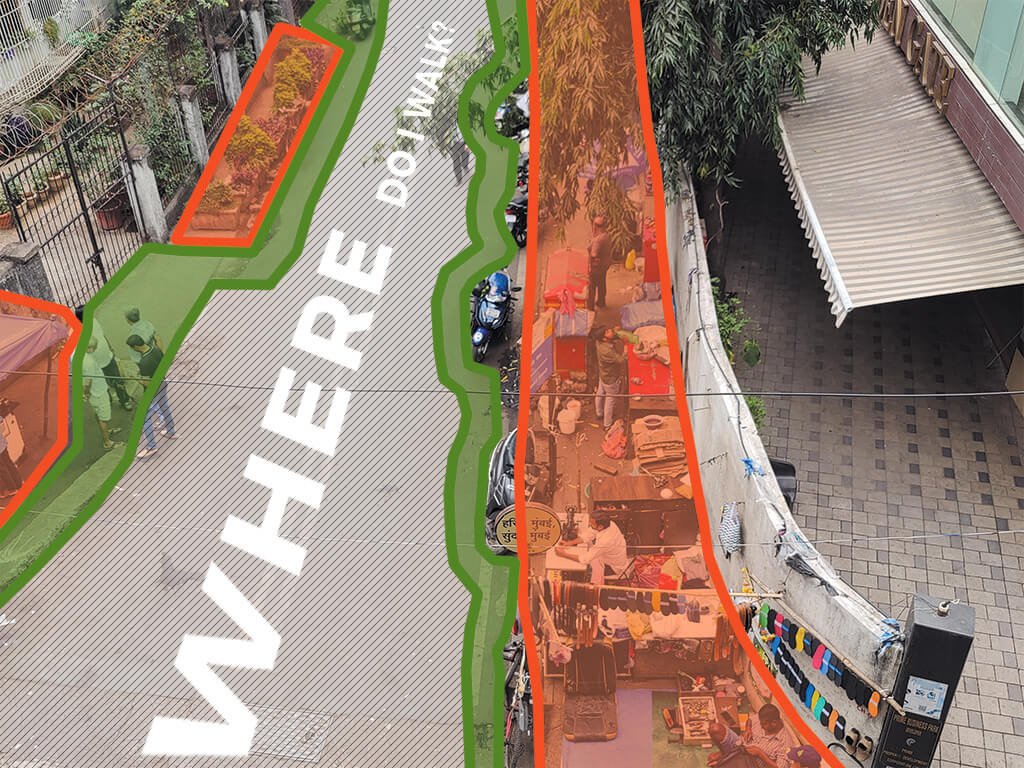

In many cities, well-built and maintained pavements are seen in select areas where the political or financial elite live and work while most other areas, including the ones with high footfalls, either have no pavements or have unusable ones due to poor design and maintenance, or are competitively claimed by different people. That people have to fight for pavement space as pedestrians or hawkers, pitted against each other, is an unfortunate paradox in India’s cities where walking is the most common mode of mobility and the informal economy on pavements supports millions.

In this video walkthrough across the residential-commercial hub of Vile Parle, Juhu and Irla in Mumbai, students, shoppers, hawkers, regular walkers, and older residents talk about what the lack of pavements means to them and demand better pavement space.

Pavements or footpaths are the intervening space between roads and buildings, primarily walkways or shared spaces for informal activities. They can host informal art and performances, protests and strikes, food and fun, hawking of goods from the perishable to non-perishable, and services such as key-making, footwear-repairing, even men’s grooming. They are also transient parking spaces and the last resort for a city’s homeless who cannot even afford slums. Pavements support life in cities – and democracy too. Yet, little attention is paid to their planning, construction, and maintenance; financial allocations to pavements in annual civic budgets tend to be abysmally low.

Why are pavements an afterthought or near-absent even after data has consistently shown that pedestrians suffer the maximum road fatalities? Why do they barely appear in discussions about urban mobility, transport plans and government budget allocations? Why are they excluded from environment policies, specifically to counter the Urban Heat Island effect? The answers lie in the obvious: Pavements or footpaths are seen as mere corridors for movement of people, optional and residual spaces which are made after constructing roads.

The obvious gap in planning

The narrow view of pavements, or sidewalks as they are known internationally, is reflected in the prevailing urban planning paradigm which sees city-making in a limited automobile-centric way keeping private cars – not people – at its core. In this perspective, roads are critical infrastructure but pavements are optional, not necessary spaces to meet people’s needs of walking, hawking, and bonding. So, they remain badly-constructed corridors for pedestrians, barricaded to ostensibly keep the walkers safe. Hawkers with their informal markets, a significant economic activity, do not even find an expression in this planning paradigm.

At the heart of the perspective that pavements are dispensable features of the built environment in cities lies the neo-liberalism worldview which places profit and wealth above all else and plans the built environment to support the wealthy. This segment of a city’s population owns and uses cars; rarely do they use public transport and or walk even short distances. It follows then that roads, bridges, flyovers, and connectors which make private transport faster and seamless are discussed as critical urban infrastructure; not pavements.

Ironically, people who use pavements as pedestrians, vendors and loiterers out-number those who use private transport, but officials who deliberate road alignments and intersections, even signal times at traffic intersections, hardly give a thought to pavements. This is perhaps traced to the post-independence master plan and grid-driven approach to city-making, inspired by the American and European city plans, though India’s cities historically evolved as walking cities. The National Urban Transport Policy, in 2006, finally recognised that cities have to be designed for people but mandatory requirements for pavements and other intervening spaces did not follow. State and local governments, tasked with pavement allocations and construction, give varying degrees of importance and attention to the issue.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

Who pays the cost of bad or no pavements?

Ultimately, common people suffer. Either pedestrians lose their lives and limbs dodging vehicles on the roads where they are pushed to, or hawkers do not find adequate and legitimate space for their wares, getting into battles with civic officials and pedestrians. The pedestrian versus hawker battle is a continuing one in most cities; it does not have to be so. The lack of comprehensive and inclusive planning creates this free-for-all, making pavements chaotic and hazardous.

Pavements can be a source of joy. Cities with planned and well-maintained pavements which feature aesthetic street furniture and appropriate signages are in a league of their own. Such pavements offer space for people to amble along, spend time at kerb-side tables that cafes put out, shop at hand carts or stalls, or simply loiter. Walking becomes pleasurable, not hazardous. The pavement or streetside economy flourishes too without hindering anyone.

Safe walking is a key purpose of pavements though not the only one. The average walkability in India’s cities is low, especially for children and the elderly, which means fatalities and injuries.[1] In 2021, India’s pedestrian fatalities numbered nearly 29,200, exceeding the combined road fatalities of the European Union and Japan; 60,000 more pedestrians suffered injuries, said a report based on the union Ministry of Road Transport and Highways (MoRTH) statistics.[2] [3]

Pedestrian deaths account for 30-35 percent of all road deaths in India but, in cities, they are nearly 65 percent, according to transport analyst and IIT-Delhi professor of transport Dr Geetam Tiwari.[4] Delhi topped the list for pedestrian deaths in 2022 with 629 fatalities and Bengaluru was in the second place with 247 deaths, marking 25 and 50 percent rise respectively over the previous year.

The “fundamental flaw” is in the road design which mostly caters to the smooth flow of motorised transport, averred Dr Tiwari, reducing pedestrians to “helpless trundlers” although walking trips are the largest majority of all trips in cities.[5] A staggering 63 percent of all trips in India’s cities are on foot; nearly 45 percent people walk less than five kilometres to their workplaces, more women walk to work than men.

The high pedestrian count is at odds with the poor walking infrastructure; India’s cities score low on the walkability index used internationally. People walk short distances, last-mile to home, to schools and offices, to markets, for care work or leisure in hazardous conditions – because they are forced to. This allows authorities to take pedestrians for granted.

Delhi prepared a walkability policy in 2019 but it has not meant a walkable city for all.[6] A recent study[7] asked pedestrians reasons for avoiding pavements even where they exist; parked vehicles, mindless obstructions, bad or uneven walking surfaces, broken alignments were some reasons cited. If pavements are seen as critical infrastructure, their design, construction, and maintenance would be better.

Illustration: Shivani Dave

The ‘conflict’

Among the most contentious use of pavements in India’s cities has been the growing presence of hawkers or vendors. If informal economy is an intrinsic part of cities, then informality will find and occupy common or open spaces. In principle, there can be no contradiction between pedestrians and hawkers using pavements; the conflict, between one set of common people and another, is cleverly engineered by the power elite in cities and by the absence of a comprehensive plan which acknowledges the presence of hawkers on pavements.

This can be resolved if the local authorities clearly mark out hawking or vending zones and issue a fixed number of licences supported by the space on pavements; once issued, local officials should not allow more or unlicensed vendors in return for payoffs.[8] Hawkers’ associations such as the National Hawkers’ Federation have been exercised about this and hold regular deliberations.

Without enough walking room on pavements, we will not even have customers for our wares; so, it is in our larger commercial interest to have pedestrians on pavements, they say. Importantly, it has been almost 10 years since the Street Vendors Act, 2013, was passed protecting the urban street vendors’ right to hawking, recognised as a fundamental right under Article 19 (1) (g) of the Constitution, but vendors are not included in the planning of cities. However, local, state and central policies on hawking zones rarely honour this or provide space for both pedestrians and hawkers.

“The reality is that vendors and pedestrians have a natural symbiosis because the former need a steady and smooth flow of people for their businesses to flourish,” states Jay Vyas, activist with the Federation. In various courts across India, over time, the right of pedestrians over that of hawkers have been upheld while others have taken a more accommodative stance such as barring unlicensed hawkers from pavements.

Bhubaneswar, the capital of Odisha, regularised and assigned designated spots or kiosks on footpaths in a few areas under new rules in 2015. There were more than 2,600 kiosks in the city.[9] This approach can be the template for other cities as it acknowledges the presence of hawkers and includes them in planning and design.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

Pavements as green spaces, democratic spaces

The role of pavements in greening and cooling urban areas is often glossed over. Pavements can be a significant part of the green infrastructure in cities supporting a wide and rich biodiversity, their surfaces can be made porous for rainwater to seep into the earth to increase the groundwater level and reduce the water-logging on roads.

‘Cool pavements’ are increasingly being seen as the way forward and surface materials used are given a thought to in some cities, but in sporadic and scattered ways. The international collective C40 prepared a guide for cities on cool roofs and cool pavements.[10] Permeable surfaces help cool down a neighbourhood helping to address the Urban Heat Island effect.[11] The National Green Tribunal, in 2013, had raised the issue of rampant concretisation of pavements which led to a debate on surfaces but there has been no standardisation or guidelines on materials.[12]

In fact, the trees around which the pavements were constructed tend to be at risk as the concretisation suffocates its roots. Alarmed by this, NGO Kalpvriksh approached the Delhi high court nearly 15 years ago which led to the mandatory six feet free non-constructed space to be provided around trees on pavements. But most pavements are not wide enough to allow the space around the trees.

Policies on how pavements can be the defence against climate change impact and help augment the natural environment of neighbourhoods can be formed when there are clear plans for pavements. Beyond this, pavements as democratic and social spaces demand attention too. When they are shrunk and thinned out, it reflects a marginalisation of people and their rights. Spatial rights are democratic rights, after all.

The way forward

The long-term response would be to move from the automobile-centric urban planning to people-centric planning and making of cities. This means cutting down the dependence on motorised transport, diminishing the need for roads, and augmenting the non-motorised options which include walking and cycling. This also means re-imagining the proportionate role of private transport to keep to a minimum while investing to expand public and intermediate transport modes.

Both these moves call for a structural shift in the urban planning and design edifice itself. This is easier said than done given the enormous stakes that the wealthy and wealth-creators have in continuing with the system that has best served their interests. However, consistent pressure from people, especially civic activists who dedicate time and energy to the construction-maintenance-accessibility of pavements could help move the needle here. The onus, unfortunately, falls on individual citizens and citizens’ groups.

Within the road infrastructure, making more roads one-way to help move the traffic more efficiently, reducing or eliminating the U-turns on most roads, applying heavy penalties for lane-cutting and wrong-side driving, penalising over or under-speeding all help to keep the road traffic moving smoother. This reduces the need for wider and wider roads, allowing more space for constructing and expanding pavements in a planned manner.

Globally, there are debates on sidewalks designs to make them more accessible and safer for all people. India’s cities could start by turning neighbourhoods with large footfalls into people-friendly pavement zones. Walking or hawking should not have to be so dangerous or difficult.

Cover illustration: Shivani Dave