The book, Cult of Play, documents various ways in which children across Mumbai’s diverse demography and geography play. Edited by architect, activist and designer Martina Maria Spies and architect, designer and urbanist Pritika Akhil Kumar, the book was published by the People Place Project. It emerged from Spies’ work of building play spaces, especially in the neglected neighbourhoods of Mumbai, through her organisation, Anukruti. She joined hands with Akhil Kumar who is the founder of Co:Lab, a Chennai-based design and research collaboration that explores urban regeneration, public space and participatory spaces.

Speaking to Question of Cities from Vienna, Spies highlights the differences in the approach to play in Europe and India; here, play is sidelined for studying or work. “They don’t understand that play is a medium of learning,” she says. We don’t need large esplanades, says Akhil Kumar, because liminal spaces, “more human in scale,” make it easier for children to interact with each other.

How did the idea for this book come about? Why did you choose Mumbai?

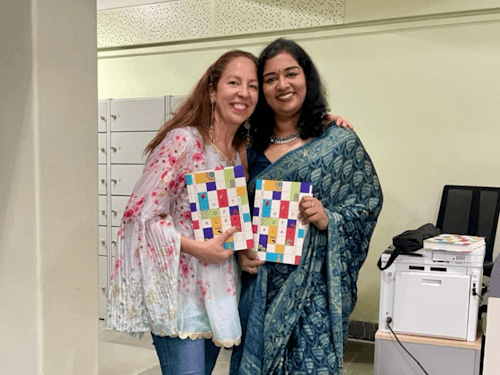

Martina: It arose out of the research project,[1] which we conducted with the TU Wien, public research university in Vienna, Austria. We chose three neighbourhoods in Mumbai — Dharavi, Juhu beach and Khar Danda — to document the cultures of play. It was an interesting and long-lasting project. We were associated with the Tata Institute of Social Science and Dr Amita Bhide was also a part of it. In 2019, I met Pritika at a conference in Delhi, she’s my sister forever and friend. Cult of Play would not exist without Pritika.

Pritika: Marti had done the original research. When we met in 2019, we got chatting, liked each other’s work, and she asked me if I would like to contribute a chapter for the book. I agreed. We then invited more writers because there were gaps to be closed about Mumbai’s urban context and the opportunities for play. That also led me to design the book. It’s been a long process but I think both of us are quite satisfied with it. We are not finishing this research and putting it away. We plan to look at how we can actually develop this design tool. We are also looking at other places.

How did you put together the book cover?

Pritika: The research championed the view of children as experts of their own environment. We wanted to capture that on the cover. The play elements on the cover are all localised ones which we are familiar with in India. The idea was to keep it colourful and engaging in representing the children and their thoughts while recognising it as a narrative to inform adults.

What factors govern play in India’s cities?

Pritika: This is a vast topic but I think as time has gone by, the conditions for play have been regulated further and further. The way our parents played is not the way we played as children and it’s not how children play today. Because play is constantly being pushed to the margins in our urban environment, in the blind pursuit of infrastructural progress, we have pushed out all the open spaces, empty spaces, green spaces from our urban narrative. If you see the developed cities, there is enough space for play, for playful exchange, even among adults. There is space for holding an identity, for experience with each other, without being super-surveilled. In London, you have parks like Hyde Park where you can walk any hour of the day. In our cities, we have particular timings to enter and exit a park.

Of course, it’s not a direct comparison and there are more complexities at play here. In post-colonial cities like ours where many people are still working to secure roti, kapda, makaan, it might seem frivolous to say that we need open spaces but, during the pandemic, we saw the importance of play to remain physically and mentally healthy. If you see our urban plans, whether Mumbai’s Development Plan or that of any other city, there’s very little reference to open spaces as part of a strategic vision. Parents think play is not as important as academics and schools are moving towards a curriculum that does not prioritise play.

Martina: In Austria, play is a part of the curriculum. Every two or three hours, we had an hour to play. During fieldwork in India, I saw that play means games with rules, free play is not allowed. I saw that, in India, play is a luxury.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

Unfortunately, during our fieldwork, we saw that the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) teachers don’t understand the importance of the concept, they think play is not important, that it’s better to have tuition classes. But they don’t understand that play is a medium of learning. I think first parents, teachers should understand the importance of play. Children already know it.

How does the inequality in the city influence children’s play?

Pritika: Within gated communities, children tend to have access to some space to play, in the parking lot or circulation areas, but in the informal settlements there’s no access to space at all. Children play alongside traffic. I was doing fieldwork in Parrys Corner in Chennai where I asked the children playing on the streets what they would like to change. They said: “We would like to have space to play.” I pointed to the compounds of temples, mosques, and churches around. They said they get beaten up and thrown out from there. One of the main issues about inequality is the access to space. That’s why we felt this research focusing on informal settlements was important; the space crunch is more intense in these contexts.

What role do children’s interactions with nature, the green spaces and water bodies, have in their development?

Martina: Water is a tremendously important element of play. When you don’t have play spaces, then water, especially at the start of the monsoon becomes significant. It’s so wonderful, it almost makes me cry. I had a lovely experience during fieldwork when children developed their own games, counted water drops. It was amazing. There are so many natural elements in the city and children are so creative. In the book, we developed an abstract design tool in which water was a key element. And each and every tree in Juhu was part of the fieldwork. Of course, you need playgrounds but even in dense neighbourhoods in Mumbai and Chennai, nature is still present.

Pritika: The chapter by Aslam Saiyad looks at how tribal Warli children grow up in areas around the Sanjay Gandhi National Park, how children learn through their interaction with nature and with each other in relation to nature. That’s something constantly denied to children growing up in concrete jungles. Their learning is very different. We might play in our schools, go to the gym, speak English but intuitively, we are not as connected to nature. That disconnect might be a reason why we see different problems in urban settings.

Girls are often discouraged from playing after a certain age. How can this be changed?

Martina: We had a book launch and discussion at TU Wien. In Mumbai, during the fieldwork and while building playgrounds, we observed that girls are more invisible than boys. The boys are very free, they have unstructured lives, they play cricket, football, everything. Their girls’ lives are far more structured. They have to help their mothers with household chores. The girls are always in the corners — always. So, I was genuinely surprised to see girls playing freely at Muslim Chowk in Dharavi.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Korinna Lindinger, one of the writers in the book, doing her PhD in Vienna, said the gender aspect is extremely pronounced there too. Boys play football there, but there are no girls. And there are so many layers in the 18th district – you have migrants but it’s also a cottage quarter with wealthy people. Yet, only boys play. Corinna told me about this project where they created a small area for the girls to train in football. After about six months, they started playing with the boys. That in-between space helped build their confidence; it became a natural transition. Even the boys said, “Oh, they can play like us!” These kinds of in-between spaces can be really meaningful.

Pritika: Societal roles and prejudices play a big part but it’s also a safety concern. I wonder if the girls at Muslim Chowk were more empowered to play there because it’s a chowk, a monitored space. In that sense, I think of Jane Jacobs’ concept “eyes on the street” which stresses on the importance of activated public spaces. Parents can keep an eye on their kids from the periphery of such spaces without directly intervening.. That’s an important step. We also need awareness campaigns on why it’s important for girls to play.

How do you see play in controlled spaces like malls or designated spaces with a ticket? How does this influence children’s view of the world?

Pritika: Children would be shaped in similar ways to how adults are shaped by this. Malls and regulated spaces where you have to pay or fulfil conditions to enter are not really public spaces; they are pseudo-public. They have the appearance of being public but there are barriers to entry. They create this fractured society where children start learning who is savoury and who is unsavoury. That’s dangerous; it creates a lot of prejudices in the young minds.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

In your imagination, what is a play-friendly Indian city?

Pritika: I don’t think we need the vast open spaces that European cities have because that’s not how our cities were planned. We didn’t have expansive esplanades and squares. A realistic vision is to have pockets of spaces in cities—liminal spaces, abandoned spaces, which can be reclaimed as play spaces that children are free to use. There is wisdom in developing these at the neighbourhood level. Large spaces can often be intimidating, especially for children. When you have more pocket-sized spaces, more human in scale, it’s easier for children to interact with each other without being completely isolated. New York City has the High Line Park which was once a railway line as well as parklets on streets which can offer small moments of rest and relaxation. This should be our approach.

Martina: If you read the chapter ‘Playing the Gaps’ by Rekha Desai, you will see that there is space in Mumbai but it’s unused. There are pockets of space. The concept of public space is completely different in India than in Europe but the in-between pockets are much more important. Even then, you have to create awareness of the importance of play.

How can play be made a part of urban planning?

Pritika: A lot of work is being done across the globe on creating policies about play. In the Indian context, unfortunately, this is limited to prescribing the scale of these spaces. Most of our city-level strategies state that there needs to be a park within 500 metres from homes, but there is nothing that describes how people obtain access to these spaces. Having isolated bits in the city for children is problematic. We need to start approaching play as the way we interact with the city, by allowing moments of playful interaction all across. Our plans have no vision regarding play.

Martina: Architect and urbanist Neera Adarkar said that there are policies in Mumbai which state that there has to be a playground and open spaces for every habitant. But, as Pritika mentioned, are they accessible? Shivaji Park is one of the most democratic spaces. People can sit on the low boundary wall and there are no gates. You can’t compare it to parks in Vienna but it’s a very democratic place, built and designed for, of course, political reasons.

What steps can local governments take on play and leisure spaces?

Pritika: First of all, to have a play policy is a good start. To define that is something we have tried to do. To involve children and the community in understanding how play environments can be created for them is good. What we have found is that children are aware of what they want or don’t want in their spaces; they are imaginative and their inputs are necessary to create spaces for them. The leisure spaces for adults should be within the same space, not a separate space.

Experience shows we don’t need much in terms of equipment or solid structures. Children are adept at finding opportunities and their moments of play even with bamboo sticks, ropes or whatever it is. The starting point should be to clear the in-between spaces, abandoned or in disuse or misused now, and make them available to children and adults. Then, children need to be empowered to shape their own spaces, as Martina has done through her research projects—to have children paint their play spaces, do some planting and so on. The point is that the process needs to start.

Martina: Through our work at Anukruti, I found that the mothers also love to have space for themselves. It’s a very dynamic process here in Mumbai; spaces get dismantled quickly. Two-three play spaces by Anukruti disappeared overnight perhaps because of lack of ownership. In Europe, we learn that the world outside is even more important and you create wonderful pockets of ownership of public, open, and joyful spaces.

Jashvitha Dhagey is a multimedia journalist and researcher. A recipient of the Laadli Media Award consecutively in 2023 and 2024, she observes and chronicles the multiple interactions between people, between people and power, and society and media. She developed a deep interest in the way cities function, watching Mumbai at work. She holds a post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic.

Cover photo: QoC File