Climate scientists claim that whereas cumulatively the total rainfall may remain same over an area, there may be a redistribution of rainfall, due to climatic factors, with long dry spells followed by extreme rainfall for a day or two. This means an increased incidence of flooding as the stormwater drainage system of most Indian cities is not geared to handle excess rainfall within a period of a few hours or days.

Mumbai’s stormwater drains had a capacity to handle 25 millimetres per hour (mm/hr) of rainfall, which was upgraded to 50 mm/hr after the July 2005 flood. But, the ‘Maharashtra State Adaptation Action Plan on Climate Change’ notes that if an extreme rainfall event like that of July 26, 2005, occurs again, then several areas would be “flooded even at an augmented drainage capacity of 50 mm/hour”.

It is important to note that the stormwater drain network does not refer to only human-made engineering structures such as huge pipes, water pumps, and embankments. Most Indian cities have a natural drainage system, consistent with its geography, which is a network of small rivers, rivulets, streams, nullahs, ponds and creeks that from time immemorial have been draining the run-off.

Apart from hundreds of kilometres of road-side drains, the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) has a network of 261.52 km-long major nullahs (more than 1.5 metre wide) and 411.56 kms of minor nullahs (less than 1.5 metre wide). These major and minor nullahs are the natural water courses of the city which includes rivers such as Mithi, Oshiwara, Dahisar, Poisar, and their many tributaries and distributaries. Over time, this has been treated as dumping grounds for waste disposal. Nullahs are now associated with dirt, stink and filth.

Credit: Creative Commons

Natural resources keep city afloat

Apart from these water channels, there are other natural resources such as hills, salt pan lands, wetlands, beaches, mangroves, tidal zones, and the national park that help keep the city afloat. But these natural areas have been systematically ignored or viciously attacked by planners and government agencies. The draft Development Plan 2034 (DP2034) does take note of ‘natural areas’ but there is lack of clarity on their extent or spread. It mentions a total natural area of 7,537 hectares; however, the Open Mumbai Map and Exhibition (2012) had mapped 14,493 hectares of natural areas in the city.

The natural areas have more than just ornamental value. They provide a gamut of ecological services, including the most crucial and lately recognised aspect of Climate Change mitigation and adaptation. As freak weather events increase, the natural areas can help Mumbai and its citizens mitigate the adverse impact of Climate Change – as sea levels rise, mangroves can help protect the shoreline; during extreme rainfall, salt pan lands and wetlands act as holding ponds and reduce flash floods; rivers can convey excess run-off, recharge the groundwater and keep salinity ingress at bay.

The natural watercourses in cities can also help deal with storm surges which are abnormal rises in sea level generated by a hurricane or other intense storm over and above the predicted or normal astronomical tide. Recent research papers have recorded how Mumbai is facing increasing storm surges and runs a high risk of submergence of large areas.

Cities across the world have realised the value of their natural areas and are making them an integral part of their planning process.

Controlling nature for our interest

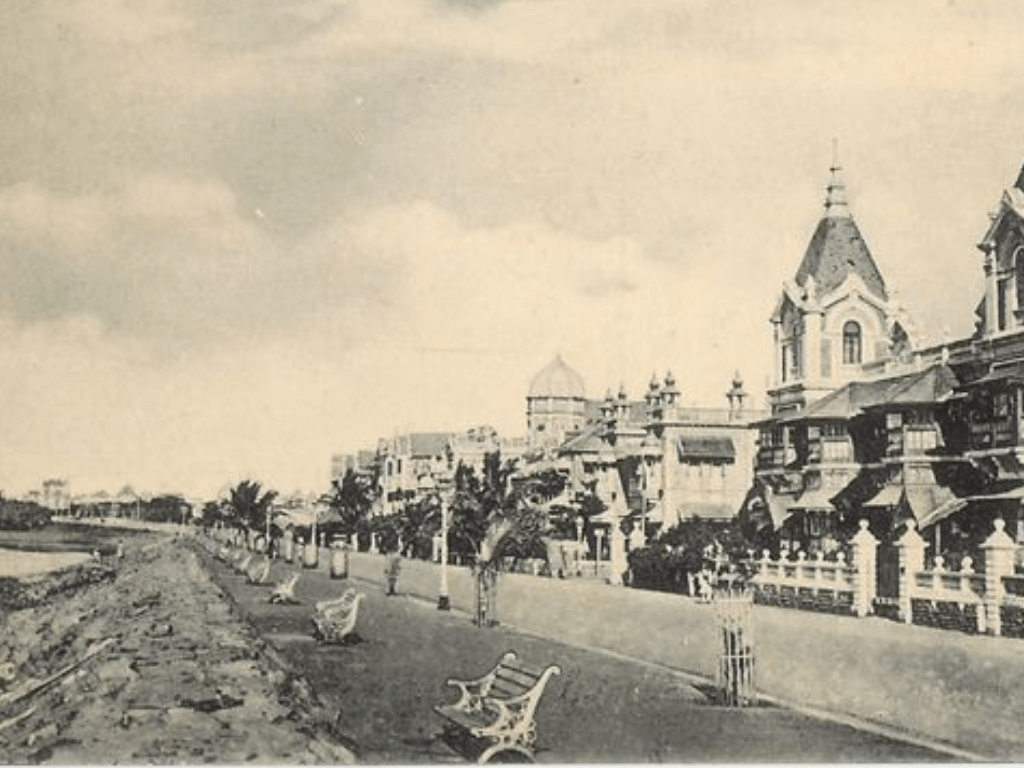

As one delves into the physical and geographical history of Mumbai, one can see a clear link between the city’s past and its present, especially how the paradigm of fragmented development adopted by the British continues even today – at the cost of natural resources.

The history of Mumbai is marked by human attempts to overpower the forces of nature. There has always been a tussle between land and the sea. The idea was that nature has to be controlled for industrialisation and used as a resource. From time to time, efforts have been made both by private entities and government authorities, starting from the British period, to do land-filling and create land for city’s residents.

The idea was to demonstrate human power through engineering (land-filling, sea walls, tetrapods) and money. Some efforts were partially and temporarily successful, others instantaneously increased tensions with the forces of nature. Though the historical trend is to overpower nature, it is futile. Instead, the new strategy should be to build with nature, not against it or by taming it.

The watercourses of the city criss-cross its entire length and breadth, but have no connect with its people. The British unified the seven islands to create land and spur growth, but what is needed now is the unification of the city with its ecology. Mumbai comprises open spaces and green areas including wetlands, mangroves, rivers and creeks. In the present development paradigm, these natural resources are disassociated from the city and its residents though they carry several ecological benefits and are an integral part of our response to Climate Change. It is imperative that the historical injustice meted out to the city’s natural resources is acknowledged and reversed. Therein also lies Mumbai’s adaptation to Climate Change.

Natural drainage system: Ignored then, neglected now

Land-filling or creating land in the sea meant a new challenge of keeping tidal water away and building a good drainage system. This challenge continues till date.

The history of the drainage of Bombay commences with the old main drain, constructed about around the end of the 18th century. It was merely an open nallah discharging at the Great Breach but was gradually covered between 1824 and 1856 from Esplanade to Pydhonie and Bellasis Road. It was furnished, after the construction of the Hornby Vellard, with a fresh outfall at Varli (Worli).

As urban areas increased, an outfall nearer the town and a more constant delivery of sewage into the sea became essential. Thus, in 1842, sluices were constructed at Love Grove and connected with the upper part of the channel by a new cut and subsidiary connections. By 1856, there were altogether 8,201 yards of subsidiary drains, nearly 1,268 yards with direct outfall into the harbour, and 2,634 yards falling into the Back Bay. Even this was not sufficient to take care of stormwater drainage and sewage disposal.

Several schemes were proposed to build a drainage network in Bombay – without much success. For instance, the one approved in 1863 could not take off due to the location of the outfall. In 1878, a project of Rs 27 lakh was launched to construct a main sewer from Carnac Bandar to Love Grove and finally erected in 1884. Meanwhile, the Fort area was re-sewered by the close of 1889 at a cost of Rs3.98 lakh. House connections and pipe sewers were completed in Girgaum in 1891 for Rs7.95 lakh, and in 1884, depots were erected for collection of night soil which was discharged into new sewers and carried out to Worli. By 1909, the city had about 200 miles of underground storm-water drains and 116 miles of sewers.

Up to 1906, the drainage department of the municipality was divided into two branches, a special branch for the construction of new works and an ordinary branch for the maintenance of existing works and supervision of house-connections. These were merged in 1907 under a qualified deputy executive engineer (drainage) who was aided by two assistant engineers, a chief inspector, several inspectors, a head plumber, a head surveyor and a full clerical establishment.

Apart from the artificial drainage channels built by the city administration to keep low-lying areas from getting flooded, Mumbai had, and still has, its natural drainage system in the form of rivers and other watercourses.

The earliest historical mention of rivers of Bombay is by Antonio Bocarro, (Livro das Plantas das Fortalezas, quoted by Da Cunha, Origin of Bombay, pages 169-170) record-keeper under the Portuguese. In 1634, he described thus: “Mombaim is a broader and deeper river than any in this State of His Majesty. It lies eight leagues to the south of Bassein and to the north of Chaul. This river is of salt water, through which many rivers and creeks from that region disembogue into the sea. There are no sand-banks, shoals nor shallows, except a rocky ridge which juts out from the land-point southwards and extends half a league to the sea.”

The Gazette of Bombay City and Island (1909) refers to creeks and rivers thus: “The two chief creeks, running inland from the harbour, are the Dharamtar and Thana creeks. The former, at the head of which is the Amba river, extends from Kansa (Gull) islet eastward for 31 miles and affords good anchorage for small vessels at its mouth. The latter, opening into the northern part of the harbour, runs for two miles from the village of Trombay to Thana town, and has a width of 41 miles, which gradually narrows as Thana is approached. The creek is lined by mud banks and mangrove swamps and contains two small islets, one being five miles from Bombay and the other about two miles south of Thana. The Amba river runs 21 miles to Nagothana, Kolaba District; while the Panvel river, which debouches into the harbour immediately north of Hog Island, extends ten miles to Panvel town in that district and is navigable by small vessels for five miles from the entrance.”

Regarding the rivers of Thana, the 1882 Gazette notes that “during the rains they bear to the sea a large volume of water, but in the fair season the channels of most of them are chains of pools divided by walls of rock…So greatly does the tide change the character of the rivers, that most of them have two names, one for their upper courses as fresh water streams, the other for their lower reaches as salt water creeks”.

Rapid development, shrinking open spaces

The Maharashtra State Gazette states that the systematic development of Bombay’s suburbs in Salsette, to the north of Mahim and Sion causeways, started shortly after the First World War when the Government of Bombay established a development department. The immediate result was the drawing up of numerous town planning and suburban development schemes. These conceived an aesthetic layout of the most suitable areas to the north of the Mahim Bay, had provisions for large open spaces, residential and shopping areas and a limited industrial development in selected localities.

The provincial government inaugurated a state-aided co-operative building scheme to help people with small means to own their houses in these new suburbs. Controlled and regulated by the collector of the Bombay Suburban District in his capacity as the Salsette development officer, these buildings had surrounding open spaces within compound walls. Khar-Bandra development scheme was pushed ahead as a model one and was followed by others in Vile Parle, Santacruz, Andheri, Ghatkopar and Chembur. These presented to the European visitor reminiscences of western suburbs of London, with rows of neat buildings on well-laid out roads lit by electricity, and served by the suburban train system.

The suburban district developed rapidly into the playground of Bombay, with a large number of clubs and recreation grounds as social amenities. Juhu, Versova, and Marve-Manori started attracting holiday crowds and picknickers. Administration in the suburbs was in the hands of a number of local authorities, but they were merged to form two major municipalities of Bandra and Vile Parle.

However, in the 1940s, Bombay was geared towards meeting the needs of the Second World War. The financial stringency of the period did not allow improvement work. The new reclamation area along Back Bay was allotted for residential sites; Marine Drive from Churchgate Reclamation to Chowpatty started taking shape flanked by uniformly rising, similar looking five-storeyed buildings, criticised by some for the monotony and the ‘pile of matchbox’ style.

The post-independence years witnessed enormous growth. The early Five-Year Plans, taking advantage of the already existing well-developed urban and commercial infrastructure in Bombay, promoted a wide range of industries especially engineering, chemicals and pharmaceuticals. The government-appointed committee stressed the need to include a large area within urban limits for the expansion of Bombay and a master plan for controlled development.

Accordingly, the Albert Meyer-Modak ‘Outline of the Master Plan’ took shape in 1948. Though not a complete plan, it provided useful guidelines for detailed planning of areas, indicated lines along which the further growth of the city, and the planning of suburbs and satellite towns beyond. In this process of implementing this – and later plans – natural resources were systematically destroyed.

In 1954, The Bombay Town Planning Act came into being and was used to clear the Mahim woods, Sion hill and marshes. Refugees of the Partition were accommodated in improvised structures in newly land-filled areas of Chembur (now known as Chembur Sindhi colony), Antop Hill, Chunabhatti, and Koliwada; the better-off refugees settled in Sion, Mahim, Bandra, and Marine Lines. The increase in population from around 15 lakhs in 1941 to nearly 24 lakhs mere 10 years later within the city limits meant high densities and rapid saturation of built areas. Open space in the city amounting to a meagre 140 hectares, proved utterly inadequate for people.

This forced the government to expand the municipal jurisdiction beyond the Mahim Bay. Accordingly, in 1950, the municipal corporation limit was extended up to Jogeshwari along the Western Railway and Bhandup along the Central Railway. Seven years later, it was again extended to Dahisar and Mulund respectively. The city expanded northwards but at the cost of the natural areas there.

Meanwhile, the master plan went out of date. The BMC declared its intention to prepare a new development plan; the state government appointed a study group headed by SG Barve to examine housing, building materials, open space and other community needs, industrial siting and traffic. The group recommended planned development of suburbs, allocation of land for different needs, immediate construction of two expressways recommended in the earlier master plan, feeder routes in suburbs, satellite townships in adjoining districts, and a public housing programme.

From 1950s onwards, as the city and the suburbs witnessed spectacular development, marshes and salt pans of Sion and Sewri-Wadala were cleared. In late 1960-70s, natural areas in the western suburbs were land-filled for construction of houses. Bandra-Khar was the planned suburb but rapid land-filling took place in Santacruz, Vile Parle and Andheri, and feverish construction activity continued in the suburbs beyond Andheri and inwards of shoreside settlements such as Juhu, Versova, and Marve. During this period, several industries were set up such as engineering and chemical units in Powai, automobile zone in Kurla, and refineries-petrochemical units in Trombay-Chembur. These developments saw informal settlements – slums – emerge to house people who built roads, quarried hill sides and provided labour.

Rivers turn into dumpyards

Fast-paced development of Bombay, with no care towards its natural environment, meant destruction of its ecology and accentuating drainage problems. This is noted in the Maharashtra State Gazette (Greater Bombay District 1987): “Many low hills have been quarried for road and plinth material, subsequently levelled and built up. Thus, most of the low hills around Sion, Raoli, Sewri, and Dongri-Mazagaon in the city, and around Kurla-Ghatkopar, Andheri-Jogeshwari, and Marol have been reduced to ground level. Much of the initial surface drainage and streams, especially in the suburban Salsette have been so completely modified that there is practically no natural drainage in the area. The original Mahim river draining into the Mahim Bay has been dammed in its upper reaches, while the building of the Airport at Santacruz has blocked it in its mid stretches. The lower stretches, close to the Mahim Bay, have become a stinking, fastly silting up, gutter carrying polluted waters, and industrial wastes, only removed during the flush of the high tides and floods of the monsoon…”

The Gazette further notes: “The westward flowing Dahisar river draining the slopes of the Kanheri hills is no more a flowing stream; it is dammed at its upper reaches, while below in the flat terrain it consists of local pits and depressions, holding pockets of polluted drainage. In fact, due to the continuous increase in built up areas, and asphalted and macadamised road surfaces, natural drainage during the heavy monsoon rains has been so adversely affected that vast areas, and local depressions get readily flooded even with moderately heavy rains. Added to this, is the fact that most of Bombay and its suburbs is low-lying reclaimed land, barely a meter or two above sea-level, and during high tides, when the sea does not receive the sewage from the city drains, most of Bombay floats in flood-waters, often contaminated with sewerage, and hence carrying risks to health.”

The Gazette also notes how the drainage capacity of the rivers in the suburbs has reduced. “The central horse shoe valley in the hills used to be drained south by the Mahim river in the past. This river has been dammed in its upper reaches, so much so this valley today accommodates three small fresh water lakes, the Tulsi, the Vihar and the Powai, one below the other, that supply the city with its domestic and other needs of water supply. Below Powai, the river today is mostly a storm drain and a gutter of sewerage, blocked off by the construction of the Santacruz airport at its Kurla end. The lower reaches are a shallow fastly silting up drain of industrial wastes emptying into the Mahim Bay,” it notes.

Similar mention has been made of other rivers as well. “The Kanheri hill complex has a radial drainage system, with numerous rain torrents washing down its slopes in all directions. The largest of them is the Dahisar river that rises on the southern flanks of the Kanheri hills and drains west to join the Marve creek; this river, however, has been blocked to form the Dahisar project, to augment the water supply to the city to a small extent,” notes the Gazette. A number of freshwater ponds were filled up for construction purposes, it observes. “For example, the Padam Talao to the north of the Military Camp Hill, which used to exist within the present airport area. These depressions have been mostly filled up for hygienic reasons and have become built up in most cases.”

Clearly, the geographical history of Mumbai, built around fragmentation of the city from its ecology, continues till date. In spite of four rivers and hundreds of kilometres of watercourses that criss-cross the city and its suburbs, they are not substantially integrated with the city or the lives of its residents. These channels are used to convey untreated sewage and garbage. The abuse of other natural resources is also rampant. Solid waste landfills in Coastal Regulation Zones, chopping off mangroves for residential towers, cutting hills for construction – the list is endless.

This research was designed, conducted and written by the team of (late) journalist-author Darryl D’monte, architect and activist PK Das, academic and author Indra Munshi, and environmental writer Nidhi Jamwal. It was funded by PUDDI or Participatory Urban Design and Development Initiative based in Mumbai.

Cover photo: Creative Commons

There is 1 comment

अत्यंत वास्तव वादी लिखाण (Very realistic writing)