Goa’s forest cover spans over 33 percent of its 3,702 square kilometres, a large majority of which is designated protected areas and the ecologically-sensitive Western Ghats. Numerous rivers, creeks, wetlands, mangroves, marshlands, and the Arabian sea weave through the green to create one of the most rich and diverse ecological hotspots in the world. Some like Sal River have been reduced to a drain, as this report[1] showed and Zuari River has microplastics due to increased tourism, raw sewage discharge, and improper garbage disposal.[2] To protect the natural wealth, Goa’s citizens have been at the forefront, consistently taking on powerful vested interests, against the Konkan Railway and Thapar-Dupont nylon plant in the 1990s, the Special Economic Zones in 2000s, large-scale projects in road and power infrastructure, tourism and real estate to list a few. Without their intervention, the degeneration of beaches, choking of water bodies, slicing of wildlife sanctuaries, and ruthless erasure of green cover was certain.

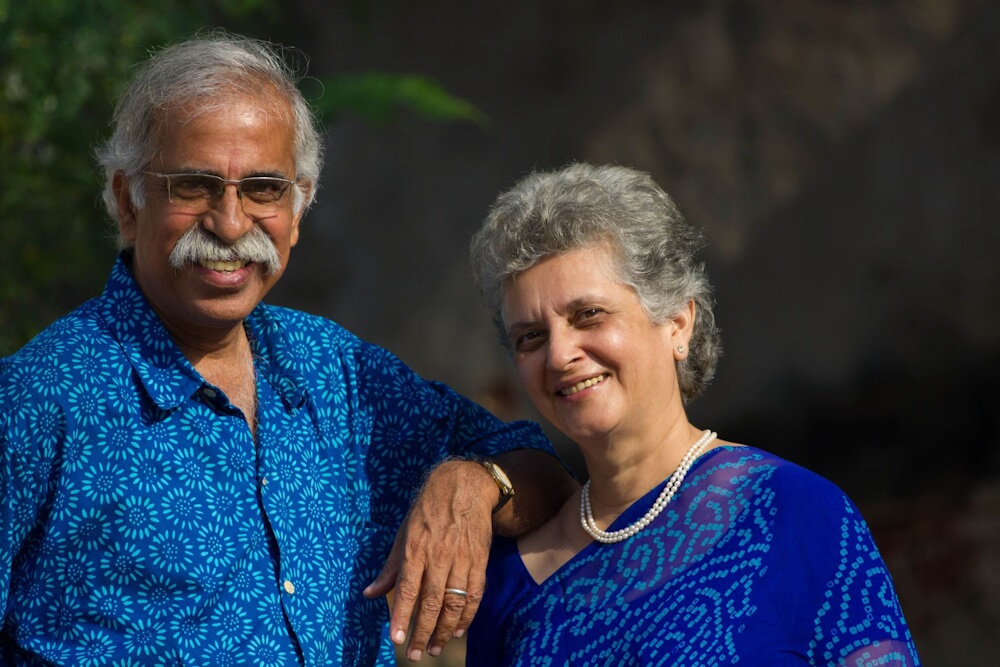

Among them, environmentalist Claude Alvares stands tall. A living legend, Alvares has led agitations on the streets and in the courts, with his advocate wife Norma. Committed to environmental causes and unafraid to take on the government-corporate nexus, the Alvares’ have been recognised for their monumental work. Claude was nominated to the Supreme Court committee on hazardous wastes and Norma was on the Animal Welfare Board of India, among other assignments. The Other India Press they run is known for publishing environmental books and The Goa Foundation, of which he is the director, filed its first PIL in 1987 to save sand dunes from miners. The couple, in their 70s, trudges to courts even today to fight for Goa.

“Though the Regional Plan demarcated 85 percent as out of bounds of development, people are being invited to Goa by governments because they have no other ideas; their only approach is to sell property to outsiders by altering the status of ecologically-sensitive areas into development or settlement zones. If we go strictly by the Regional Plan, Goa can still be saved,” says Alvares in this exclusive interview to Question of Cities on a wide range of issues.

Photo: Claude Alvares/Facebook

The citizens’ report Fish, Curry and Rice in 1993 detailed the vast network of rivers and wetlands in Goa. What is their state now?

All of them exist but the question is about the health of these ecological assets. The rivers, estuaries, riverbanks, beaches, forests, wetlands, irrigated lands, agricultural fields, forests, the Western Ghats – are they thriving or showing signs of degradation? The rivers are facing serious threats especially the Mahadayi (Mandovi). There has been a lot of illegal sand mining, with some of the river beds dropping to 20 metres in places from the original 3-4 metres. Many river banks are actively collapsing. And if you compare many beaches with photographs from the 1990s, they show major degeneration either through illegal development or mass intrusions of tourists. Their carrying capacity has been exceeded; tourist footfalls need to be reduced so that the beaches can recover.

Two major wildlife sanctuaries, Mhadei and Mollem, are being subjected to infrastructure projects and encroachments. Overall, the ecosystems are under assault and showing steady stages of degradation. But there’s good news on the wetlands front. Since the courts intervened, most of Goa’s wetlands are being notified – 15 so far, another 45 on the cards – and buffer zones have been marked. The process is slow but welcome. The turtle nesting sites on the beaches have gone up too. We have released more than 75,000 baby turtles into the sea in the last two decades. We also had more than 46 square kilometres of private forests notified as forests so that they cannot be cut down.

How would you map the macro and micro impact on Goa’s ecology from tourism, construction, and mining?

Development, I suppose, is associated with tourism. There has been an irreversible change in villages like Calangute and Colva due to mass tourism. They are no longer Goan villages, they are unrecognisable from the rubbish development in Mumbai. There are enormous traffic jams and undesirable events such as sex tourism, escort tourism, constant fights between tourists, attacks, rapes. Many Goans don’t go there.

As far as the government is concerned, development has only meant investing in highways and bridges — a four-lane highway to the old airport, another to the new airport. Bridges costing more than Rs 3,000 crore have been constructed over villages. So, you don’t have a sense of being in Goa; you start at the airport and reach Panjim. This development has done nothing to protect the Goan way of life, culture or ecology. Governments have broken apart villages, local economies and communities, and damaged many precious ecological assets such as paddy fields, khazan lands, and residential settlements. They have brutally cut hills; many have collapsed in Ponda and Pernem during the monsoon.

Now, as no land is available, the real estate industry has invaded the plateaus to colonise and develop them as residential areas. But these are cattle grazing grounds; they hold biodiversity and are water collection areas. Nobody in Goa, not even a poor man, would build a house on a plateau but this land has villas worth Rs 50 crore each for the super elite and buildings worth Rs 20 crore. People from outside Goa, particularly Delhi and Hyderabad, are investing. These constructions do Goa no good at all. They are basically a part of the transaction or speculation economy. More than 25 percent of the houses are unoccupied and there’s no management because they have been sold to hundreds who don’t know each other. But when developers, miners, and contractors influence or rule the government, then people are kept out of decision-making even if they suffer most because of such development.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Mining, or illegal mining, was stopped a decade ago due to activism. What has it meant for Goa’s ecology?

Mining was closed in 2012 and did not recover till 2015-16 when there was some recommencement which was also cancelled by the Supreme Court in 2018. Till today, only one mining company has managed to get all the permissions but its environment clearance was challenged in the High Court. Mining will be a troubled industry for a long time because those who run it don’t want to follow rules. The damage to water bodies and forests persist; there has been no rehabilitation of any site, not a single pit was closed, not a site restored. We are not overjoyed to hear that mining will restart. In a beautiful state like Goa, you don’t allow mining; it destroys nature fundamentally, takes everything even from the bowels of nature.

You have fought many legal battles for Goa’s ecology. What are the ways forward to preserve what’s left?

Legally, whatever was required has been done. We have a good Regional Plan 2021 which is the statutory land use plan (Editor’s note: After a huge public outcry because more than 72 square kilometres were added to settlement areas in Regional Plan 2011, the government denotified it and cautiously drafted Regional Plan 2021 which was the first to introduce bottom-up planning including policies to preserve the fragile ecology). The 2021 Plan demarcated more than 70 percent of Goa’s landmass as Eco Zone 1 with no unnecessary development, another 15 percent as Eco Zone 2 where restrictive development is possible and 15 percent where development can happen. The last bit is now occupied, so developers are moving to other zones. Real estate in Goa seems like paradise because everything green in the rest of the country has been destroyed, so people want to come here.

Though the Plan demarcated nearly 85 percent out of bounds of development, governments are inviting people to Goa because they have no other ideas for development and employment; their only approach is to sell property to outsiders by altering the status of ecologically-sensitive areas into development or settlement zones. If we go strictly by the Regional Plan, Goa can still be saved.

Outsiders have no commitment to Goa. They don’t live here, they buy profit-making property at Rs 5 crore and sell at Rs 10 crore. They are interested only in protecting their investment, their money floats in and out, but damages the place and people here. If the government was sincere, it would have implemented the Regional Plan and made Goa good for Goans but it’s being undermined by the chief minister and the town and country planning minister who is also in charge of forests; they have conducted themselves like brokers of the state.

Panaji used to be a well-planned city. How has it changed over the years?

It’s an unpleasant experience to go there. Roads are dug up, work is done by different contractors without coordination; a heavy downpour is enough to flood it. And since the sewage system is not the best, sewage spills on the streets. This is totally man-made – a smart city put in the hands of totally unsmart managers with the project turned into a money-making racket. There’s now a case of misappropriation of Rs 88 lakh against a key officer of the Smart City project.

I don’t go there as often now because it is a nightmare to manoeuvre the streets and it takes twice-thrice the time it did. High Court judges walked across the city to see whether their orders can help but the promises made to the HC too have been violated. Governments have tried their level best to destroy every aspect except in a few patches. Panjim is a symptom of the general malaise in the Goa administration which is steadily allowing Goa to go down the sewer.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Was the Smart City project necessary?

Many projects are dumped on cities by the central government. Left to itself, neither the city corporation nor the state government would have conceived of such a thing. But the general purpose, under the BJP dispensation, seems to be to starve them of funds and hand them projects like this one. It has nothing to do with improving the city’s environment or ensuring that the city functions better. Now, municipal officials are abusing Smart City project officials and vice versa; they don’t talk to each other, they work independently and create a mess. Even the HC failed here.

How do you see the role of people’s movements in ecological conservation? Which ones made landmark differences?

Well, though we are a small state of 3,700 square kilometres, Goa has had the largest social and environmental movements since the 1970s. We were one of the first to go against Zuari Agro Chemicals in 1974; agitations shut down the plant and forced a change in technology without arsenic. Then, the Goa Bachao Abhiyan in 2008 got rid of the notified Regional Plan 2011. Citizens rising up against Special Economic Zones saw 15 of them cancelled. The agitation against Thapar-DuPont plant for nylon production drove it out of the state. The agitations against illegal sand mining brought it to a halt and the agitations against the mining industry, which was more than 100 years old, led to mines closure. We have had hundreds of court actions to stop violations of the Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) notification on beaches and coastal stretches.

But why do people need to be engaged like this all the time? We should have time for a cup of tea, to sit by the riverside and fish or enjoy a football match, instead of constantly having to come out on the streets to agitate and act against politicians who have become contractors and brokers. Goans have been very active and successful in their campaigns; even the union environment ministry notes that they have to be careful with Goa. But for how long do people go on like this – protecting a wildlife sanctuary from a railway track, a forest from a 400-kV transmission line? The Supreme Court supports these movements. We are fighting and winning in the streets and in the courts but we should not have to do this all the time. Goa has some of the strongest environmental movements in the country simply because there is something worth protecting.

Has technology and social media made it easier for movements?

Obviously, we are facilitated. We use social media, all the available media, to ensure that citizens are aware of ecologically destructive projects. We organise meetings and hold demos, we have set up a citizens hub in Panjim for people who have problems with projects in their villages. All this is easier because of WhatsApp, Signal and other electronic media. But the agitations against Thapar-DuPont and other large projects happened before social media. So, these media may help in increasing the efficiency of work we activists do but we can continue even if the internet is shut down. Goa is a small place; we can travel from one city to another in hours and continue demonstrating, working.

Photo: Saroj Chudasama

If you had the occasion to write Goa’s Master Plan, what would you do from the ecological perspective?

The Regional Plan 2021, as I said, has been designed from the ecological perspective with demarcations of no-development zones. Hill slopes, paddy fields, khazan lands, and mangrove areas cannot be built upon. One third of Goa is protected because of wildlife sanctuaries which are about 720 square kilometres and the one-kilometre buffer zone around them is notified. Then, there is a large forest area and vast areas under the Coastal Regulation Zone. Every riverbank has 100 metres of protected zone. The khazans are an 18,000 hectares of protected zone. The wetlands are protected. More than a hundred villages are marked ecologically-sensitive in the Western Ghats Committee report. The legal protection is there but the government is trying to delete it in favour of investors or is itself involved in ecological destruction by, say, ruining a khazan for a bridge which people don’t want.

We don’t need more protection, we need people in power who are serious about implementing the protection that is already written in law. People of Goa are clear that if the ecological assets are protected as per the Regional Plan, our state will be fine for the next three generations, but if governments are not committed and lead the destruction, then citizens are unable to compete though we will agitate and there will be constant social turbulence. What can Goans do when 30 out of the 40 MLAs are real estate managers or promoters or contractors who are eager to bring or support land zoning changes to allow more development? This is the crux of the problem.

What is the response to ‘outsiders’ in Goa who are seen as responsible for ecological decline?

People from outside Goa become a problem when they change village demographics. Goan villages are small, mostly 5,000 to 15,000 people. The Bhutani project and the DLF project in Sancoale and Dabolim villages, in south Goa, would mean at least 1,500 flats and many thousands in just two survey numbers of these villages. This will change the demographic; locals lose control of their villages. The newcomers are not really concerned because they are not residents here. They are unlikely to be involved in local issues such as environment protection. They are part of the problem, not the solution. So, this mass influx is undesirable.

But there’s also the floating (seasonal) migrant labour in the construction, mining and cleanliness industries. Nothing in Goa would move without them. Migrant workers from Karnataka, Odisha, Bengal, and Bihar are essential for Goa’s economy. If we tell Biharis to return home, no garbage will be cleared. They all work very hard; they don’t damage the environment and the places they live in don’t destroy forests and trees. The outsider problem is with the wealthy like this southern filmstar Tej (RRR fame), construction companies from Hyderabad and Delhi, the ones building Rs 50-crore villas. They are obnoxious, come in with huge money, get land zones changed, destroy the system and destroy democracy. The poor migrant workers are not doing this.

I’m not saying outsiders don’t help; many of our environmental activists are people who came to settle in Goa, invested their time and plan to be here for the rest of their lives. They want to do something good and this is to be appreciated. So, there is a very recognisable class of people called ‘outsiders’ and not appreciated at all – they should remain out of Goa.

Shobha Surin, currently based in Bhubaneswar, is a journalist with more than 20 years of experience in newsrooms in Mumbai. An Associate Editor at Question of Cities, she is concerned about Climate Change and is learning about sustainable development.

Cover photo: Avenida Dom João de Castro in Panaji