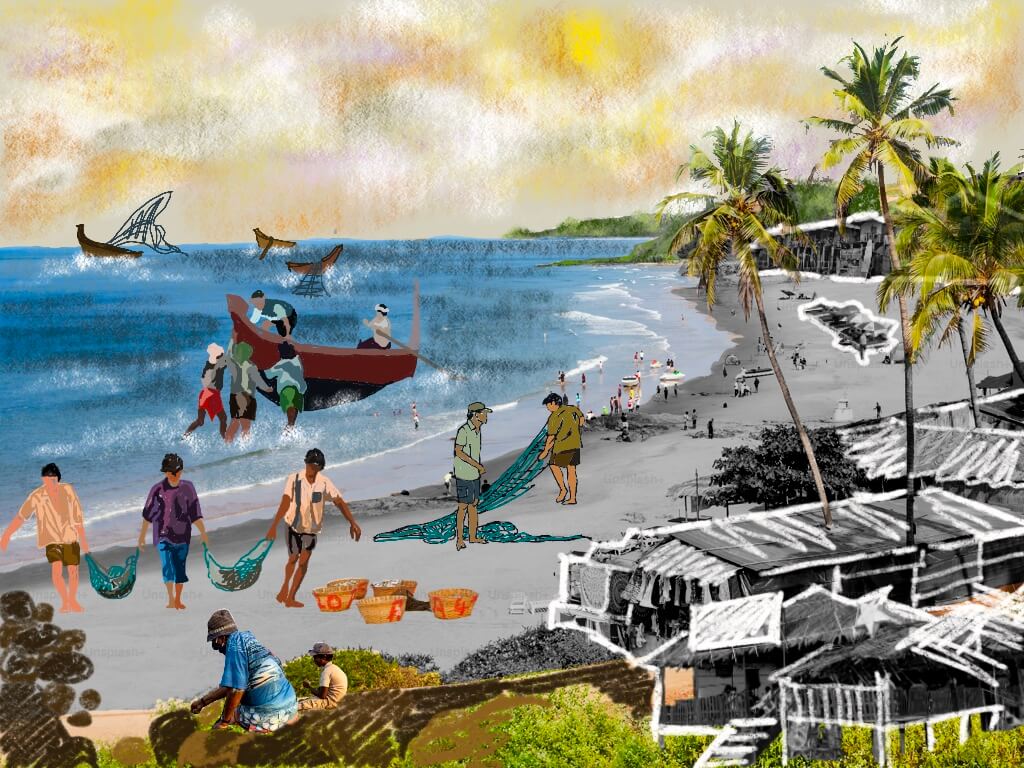

My childhood in Goa in the 80-90s was a dream – in hindsight. It was a simpler time, surrounded by nature and driven by community. We gathered at the church, and at people’s homes for festivals. We played outside, in fields and by creeks. Holidays were spent exploring jungles and picnics at the beach. The air was clean, the rivers were full, fish did not have microplastics in them, our food was fresh, our land was green and people of all religions lived together in harmony.

That Goa of my childhood now lives on in sepia-tinted photos and in people’s nostalgia. They were, as we have heard our parents and the generation before them say, the ‘good ol’ days’. Little did we think, as wide-eyed school-going kids, that the Goa of our childhood would be lost to a nexus of politics, corruption, development projects, and religious segregation.

Most recently, Goa was India’s favourite COVID-19 destination. The state kept her doors open, without testing, inviting anyone and everyone without a thought for whether our healthcare system could handle the numbers. It was not and the number of deaths proved it. The post-Covid years saw an influx of people from all across the country moving to Goa to seek a better quality of life. As #WFH was on the rise, Goa offered what many cities could not — better air, more open spaces, a sense of quiet, and less chaos. By the way, Indians started to ‘revenge travel’ and Goa became the preferred destination. The consequence of these two meant the focus soon shifted to accommodating large numbers, often at the cost of Goa’s ecology.

Every other day, my Instagram feed shows up another tragedy in Goa: a tree being cut here, permission for a new hotel there, a change in zoning laws, permission given to projects that will destroy, say, Mollem National Park. Mollem, a small village on the Goa-Karnataka border, is the path to a wildlife sanctuary and 240 square kilometre National Park where three infrastructure projects have been planned. Goans are facing an uphill battle to preserve their land and their way of life. Will they succeed?

Development has meant destruction of land

Goa is rapidly losing the very essence of what makes it such a cherished destination: Beautiful beaches, pristine forest cover, friendly people, and affordability. Instead of preservation of Goa’s beauty, much of it is being destroyed as development. A select few are benefitting, including residents, who have sold their lands and builders who have profited from constructing on it.

“I grew up in a green Goa which had a slow-paced life and warm people who welcomed people not just to the state but even their homes. However, the scenario has changed visibly. What was once green is now brown or worse concrete grey. Development was definitely needed but it could have been more sustainable than what we are witnessing. We only need to look at other cities and how they are struggling with issues like pollution, water shortages, depleted wildlife and climate change. I am genuinely concerned about my state and the direction it’s going in,” says Alroy Fernandes, Emcee and quiz master.

Some say the framework for this development was laid with the Regional Plan (RP) 2001, released in 1986, which promoted high-end tourism. The second Regional Plan 2011 promoted large-scale conversions of green zones to settlement zones. The data collected[1] by Goa Bachao Abhiyan finds that 35 per cent land conversion cases remain unaccounted for, as their original zones were not mentioned. An article published in July 2024 by journalist Gerard de Souza, detailing the 21.29 lakh square metres of green zones converted for construction in 15 months, was taken down by Hindustan Times allegedly because of political pressure. Another report[2] by The Indian Express says that at least two state ministers, politicians and several real-estate companies are alleged beneficiaries of a controversial change in land use law.

Land conversion is currently the major issue in the state – fields, orchards and other green zones are converted into settlement zones so they can be turned into construction sites. Goa’s recent controversies have involved real estate projects, and, the Opposition alleges,[3] that it reveals the nexus between the government and the real estate lobby in the state.

As Shohail Furtado, a Goan doing environmental activism on social media,[4] candidly asks me, “What else would you expect from this government?” It’s a nexus between people in power, locals who aid this, and others with vested interest in profiting off Goa’s land. An example is the Reis Magos hill denuded for a proposed luxury property in which the company has started selling villas[5] for Rs 50 crore. The unchecked hill-cutting is apparently being done without the knowledge of the Town and Country Planning (TCP) Minister, Vishwajit Rane. Faced with increasing flak, the government has proposed a fine of up to Rs 1 crore and urged Goans to be vigilant about illegal hill-cutting.

Over in Sancoale, people are protesting – with a hunger strike[6] – a mega project by a corporate that could severely affect the infrastructure of the village. Since 2021, the Save Old Goa Action Committee has been fighting[7] against a bungalow built within the protected area; the case[8] is still on. Most recently, they are questioning[9] why the government didn’t designate the area as a heritage site in the Regional Plan 2021. People in Loutolim are fighting against the new Borim Bridge which will cut through the khazan land.

Despite all the protests, the Town and Country Planning department has approved 11 applications for zone change. The lands, earmarked as paddy fields, orchard land, irrigation and natural cover[10] in the Regional Plan, will likely see the construction of luxury apartments. “It is spreading like cancer – destroying one’s area for some financial benefit. Talking to those in power is like screaming at the walls,” says Furtado, “Goa is changing and not for the good.”

There’s also the ongoing six-lane elevated highway at Porvorim which has caused chaos, traffic jams, dust pollution, and the death of many trees. Public outrage led to a huge decades-old banyan tree being granted a reprieve. The government told the High Court it had received permission to cut 616 trees and transplant four. “This development is not for people. They are just bulldozing through. I am not against development but it needs to be sustainable,” adds Furtado, citing the example of mega projects permitted without research on whether the existing infrastructure in the villages can handle this load.

Perhaps the biggest project, a source of despair and the butt of many jokes, is the Smart City Mission launched by Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Panaji, was selected as one of the cities in 2015 and the project launched in October that year. Is Panaji smart a decade later? A look around the city gives the answer – snarling traffic, construction dust, potholed roads, inadequate parking, waterlogging during monsoons. Beyond beautification and one ‘smart road’, little[11] has been done but corruption[12] has reared its head. Yet, this year, the project was expanded to the neighbouring villages of Ribandar and Old Goa.

A cycle of change

Earlier this month, X/Twitter was abuzz with folks talking about the decline in tourism in the state, with people choosing to travel to ‘cheaper’ and ‘friendlier’ Bali. A tweet showed that the number of foreign tourists to Goa had significantly declined. Goa Tourism responded citing data from the Ministry of Tourism but it was clear that international tourism had not rebounded to pre-pandemic levels. The data says that, when the pandemic hit in 2020, Goa saw 3.03 lakh foreign tourists which sank to 22,000 the following year before rising to 1.75 lakh in 2022 and nearly doubled[13] to 4.5 lakh in 2023. Domestic tourists doubled from 30 lakh to 70 lakh between 2021 and 2022.

Goans say that domestic tourists and their misbehaviour — blocking roads, rash driving, taking vehicles on beaches, littering and more — is turning away foreign tourists. Another reason is the increasing costs of dining out. Goa’s dining landscape was altered by the pandemic. As people moved en masse to Goa, culinary entrepreneurs and big names moved too. The culinary scene is booming with restaurants offering every conceivable cuisine but this has come at a price.

An average dish at a decent restaurant costs Rs 400-700; cocktails around Rs 400-900. There has been a slow decline in Goan food, now broadly restricted to token appearances on menus, in thali joints and food carts, and a handful of old-school institutions though a few Goan chefs and entrepreneurs are striving to put Goan food on India’s culinary map.

Who truly benefits from tourism? The argument heard often is that Goa earns from tourism. The time has come to ask: At what cost? Goa is losing her green cover[14] to make way for hotels, holiday homes, AirBnBs, and villas. And property prices have skyrocketed. In all, too high a price to pay. Some Goans, who are selling their land, benefit in the short run but this mass-scale conversion of land at the cost of ecology is not sustainable.

Goa’s eco-warriors

As with any story, there are positives, though a few. Goans, miscast as a lazy lot, have woken up to the dangers. Citizens across villages and cities are banding together to preserve Goa’s cultural, ecological, and social ethos – filing PILs, organising protests, showing up for marches, launching petitions and more. Armchair activists are around too. So, while much of the current narrative is depressing, Goa’s eco-warriors has been a positive for me. When I despair, I turn to them for inspiration.

Earlier this year, it was the citizens’ furore over the Goa Town and Country Planning (Amendment and Validation) Bill which compelled the government to withdraw it. The Bill sought to protect the TCP from judicial scrutiny over land conversions.[15] Many villages, mine included, joined forces to ban the musical festival Sunburn, long associated with noise, drugs and pollution. There was a strong movement demanding the resignation of Rajesh Naik, Goa’s Chief Town Planner, who gained notoriety[16] for approving the conversion of 22.14 lakh square metres of land; 30 percent of it involved hill slopes.

Claude and Norma Alvares and their NGO, Goa Foundation, have been instrumental in monitoring and helping preserve Goa’s environment. Federation of Rainbow Warriors (FRW) has been helping the farmers in Loutolim. Landscape designer Daniel D’Souza,[17] vocal on social media, has been fighting against unnecessary tree-cutting, and promoting scientific ways to prune trees. Shohail[18] Furtado makes reels and conducts in-person talks about Goa’s sustainable future. During the lockdown in 2020, citizens banded together to form the Save Mollem[19] group to protect the National Park and Bhagwan Mahaveer Wildlife Sanctuary.

Marine biologist Gabriella D’cruz, in a conversation tells me, about the extractive nature of today’s visitors and settlers (a term used for people who migrated to Goa post-Covid). “My stake is so much more than someone who thinks ‘I like surfing but I don’t care about the new fisheries or tourism policy’. I think it’s really scary because it removes the onus of accountability from this set. When people ask how to help, I say vote and talk to your local politician. It’s the only way to have a stake.”

In her book Becoming Goan, Michelle Mendonça Bambawale talks about this post-Covid Goa with chapters chronicling the change she has seen in her village, Siolim. It is Goa’s newest hotspot with new property launches every week leading to crowds and chaos. Locals came together to protest the cutting of old trees for a road-widening project. That’s when she decided to join the protests. “I never thought I would be an activist. People say ‘nothing will happen and what’s the use of these protests’ but, for me, it is about knowing that I tried and being able to sleep at night,” she says. Bambawale adds that she has learned a lot by attending panchayat meetings, filing RTIs, and the legality of cutting trees.

For me, Goa’s future lies in the hands of citizens like Gabriella D’cruz, Daniel D’souza, Shohail Furtado, Michelle Mendonça Bambawale and many others who use their voices to bring awareness and attention to its issues – and hold out the hope for change.

Joanna Lobo is a freelance journalist based in Goa who writes about her home, food and travel, and culture. She is currently a consultant at Goya Journal. Her bylines have appeared in leading Indian and international publications: Conde Nast Traveller India, Vogue, Forbes, National Geographic Traveller, Eater, among others. In her free time, she sends out a freelancing newsletter, It’s All Write.

Illustrations: Nikeita Saraf