Kolkata has been home for me in every way since the beginning of my time on earth. Its urban evolution and the scale of political complexity has fascinated me like it has many others. While Kolkata can be seen from different lenses – cultural heritage, opinionated public sphere, site of radical politics, and nostalgia to name a few – I wanted to travel a little beyond these to explore how gender interacts with the urban space.

Gender in everyday lives appears in a mundane way, almost non-existent or profane, discouraging questions and dissections. Events such as the horrific rape-murder of a woman trainee doctor at RG Kar Hospital in August this year upstage this once in a while and demand a closer look at the intersection of gender and urban space. What better way of doing this than using the lens of everyday life and walking through the city’s streets, neighbourhoods, and paras as women? This is my Gender Community Walk.

The core belief is not only to get to know the city better as a woman but also use the exploratory experience to reimagine, recreate and reshape urban spaces to feel at home. The walks both explore and reflect on city spaces which we pass every day but do not purposefully observe or feel belonged in. For example, where are the clean toilets for women, can Kolkata have gender-neutral ones, how does a queer non-binary person avoid unwanted attention in conventional female places and more questions arise. The intersectionality of socio-economic backgrounds, genders, and sexualities with city spaces is fascinating.

The walks

I have conducted six gender community walks so far in different areas of Kolkata, areas that are of immense significance to commerce, recreation, transport routes and crossings, areas of nostalgia in the south, north and central Kolkata. With walking companions, I have closely looked at the gendered experiences of walking through Ravindra Sarovar Lake via Lake View Road and Deshapriya Park, through the Indian museum, covering Esplanade Road before ending the walk at Swarnika Tram Museum. At Esplanade Road, we were harassed by vendors because we, as a group, did not want to shop. I was also mistaken for a man because I wear baggy shirts and pants, and sport short hair.

Photo: Neena

The walks have taken us to north Kolkata – on Bidhan Sarani Road till Vivekananda Road, close to Hedua Park– which taught us about the infrastructure of care. We understood how structures like tube-wells, shade under trees, and building staircases provide a space of care during hot, humid days. At a lane close to MG Road, men were gawking at us, shooting pictures and passing comments at us for loitering around. We also experienced roaks, or extended outdoor spaces, which are characteristic of north Kolkata houses.

The walk through Ballygunge Market brought home all kinds of smells of masalas, chowmein, pakoras and fresh vegetables too, but the over-powering one was of the stench from the dumping ground. The shopkeepers, we found, weren’t as bothered by it as much as by food and vegetable street vendors taking up space outside their shops. Women vendors said they felt safe here but we did not see even one of them walk alone to the nearby Ballygunge train station.

Then, I did a walk across Bijon Setu, through Cornfield Road to reach Citizens Park, and found that it was not properly lit. It has a huge fountain which becomes the main source of light when switched on. My mother, Moumita Chatterjee, who has been providing me with logistical support on the walks, asked the watchman about it. He immediately turned them on but it should not have been so.

Our fifth walk, focused on leisure, took us to Nandan, an enclosed public space. We started from Ravindra Sadan and walked to Nandan, which is opposite Exide mod (turn), passing by the Academy of Fine Arts where murals of political leaders brought forth much criticism from walking companions. There’s an amphitheatre and many roadside eateries where heavenly smells of tea and chakli, bread pakoras, fish fingers, and an assortment of desi Chinese items mix with that of tobacco. Here, women can smoke without being judged.

Typically, on a walk, we meet at a specific location and do an ice-breaker session, start the walk and simultaneously shoot photographs, observe spaces we are in and claim them or use regardless of the stares because how else do we enforce our Right to the City, do interviews with people, sit down to eat at a local place, do counter-mapping and make notes. I have had Sociology students, researchers, urban planners, administration job aspirants, doctors, even school students on the walks so far.

Photo: Raka Bhattacharyya

Beyond the walks

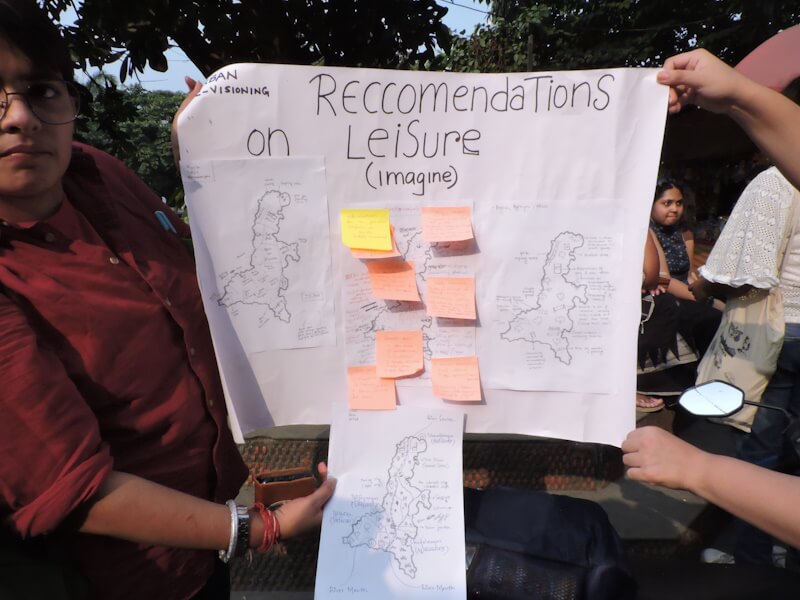

On the Nandan walk, we did a re-mapping of Kolkata. I gave every walker a blank map of Kolkata, sorted them into groups, and asked them to improve and rename spaces. Some reimagined Kolkata as a green city, one group did environmental consciousness, another highlighted the need for leisure spaces for Muslim women outside mosques. It was emphasised that temples, mosques, and churches be safe spaces for women.

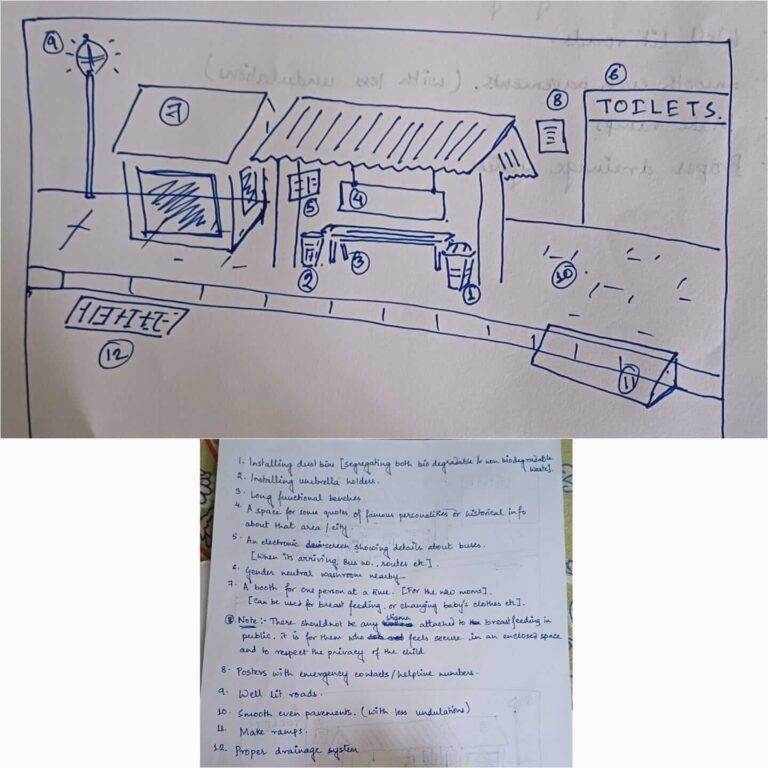

Another mapping activity renamed many parts of Kolkata with women’s or gender-neutral names. While these locations have had historical significance, our walks envisioned what the alternative formation of these spaces might look like – with different infrastructures which not only involves adding new elements but also restoring older ones as a sustainable means of survival for all communities. This, we do, through the methods of counter-mapping, body mapping and photo stories.

When I decided to study the urban environment from the lens of an able-bodied bisexual woman, it came with major constraints. Not only does my attire confuse people but that I document with my camera makes it discomforting for them, both men and women. This is where observation skills and the ability to incorporate one’s vision and intervention in ‘regular’ areas help. One of my inspirations has been Why Loiter[1] the seminal work that changed the lens of looking at cities, and the idea of a feminist city by the stellar Leslie Kern.[2]

While walking and reimaging or reconnecting with our city as women, on these walks, we are democratically putting forward our Right to the City. We are observing and questioning which areas are approachable and accessible, which are not, and why this is so. The methodology here is photo stories in which the camera becomes an extension of our visceral and intellectual self, and captures the same space from unique perspectives.

The idea in doing Gender Community Walks is that besides a different bodily experience as women of being hyper-aware of surroundings, who may touch inappropriately and so on, to see if there can be responses from us as a community. As in any Indian city, men urinate anywhere in the public. They feel comfortable doing so, we are uncomfortable about this. On our sixth walk, one walker snapped a picture of a man urinating; he then turned towards her, made a show of it, and egged her to shoot. She was horrified but soldiered on.

This blatant harassment should not have happened in a public place but it did. This feeling of being constantly restricted and suffocated, but at the same time breaking through it is a gendered experience from an everyday lens. This experience and documentation matters because we can demand planning interventions and better infrastructure.

Photos: Srestha Chatterjee

Methodologies and more

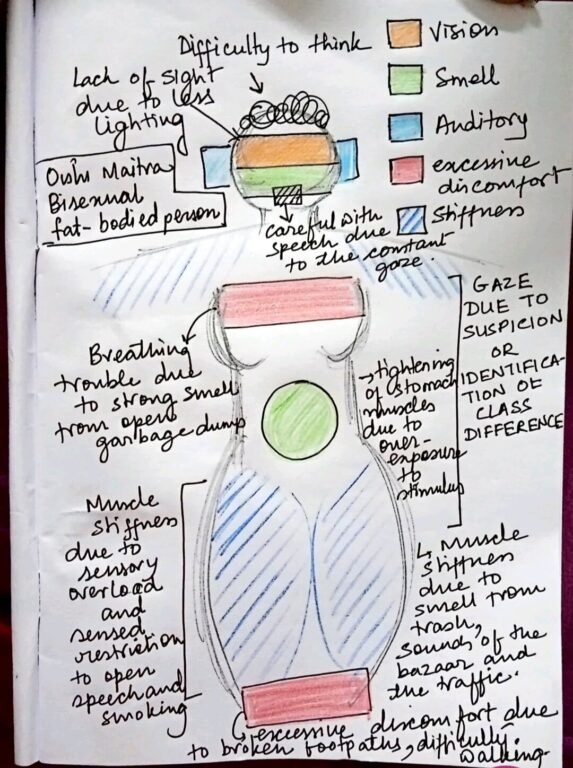

We do body-mapping to understand how we experience the built environment, which places or spaces help us and which could harm us. It is a good methodology to understand the intersection between climate change, infrastructure and gender too. Can we walk on the streets or is it too hot, are there seating places and tree-shaded areas, and so on?

Credit: Oishi Maitra

We did a social experiment in Kalighat. I wore a hoodie and started fighting with another woman, pushing her around. There were men around us – some playing cards, others shaving or playing music. They stopped doing what they were doing and simply watched; even a policeman did not intervene. When we broke out of the act, one of them walked up to us, cussed at us and said he wanted the tamasha to continue. Violence in public spaces in which women are at the receiving end is seen as a personal problem, there’s no intervention.

This kind of violence and assaults go on in homes too where the lines between private and public are harder but even in public spaces, people refuse to or hesitate to intervene. Then, onlookers as part of the ‘infrastructure’ also become enablers of violence. People are vital to urban infrastructure, hold power to change things, but rarely see themselves this way.

The body-mapping tells us about sensorial ethnography with an understanding of what the geography of a city feels for any gendered individual. This is the starting point of change. I distinctly remember what Mehr, one of our participants and a student of Political Science at Presidency University, had to say: “Even in a group, when we are walking, the gazes on us in the Ballygunge market felt like we were intruding their spaces. But if I was walking alone and gazed upon, then I would feel my identity is being intruded upon, not the other way around.”

Another participant, Oishee, expressed that men can smoke anywhere but women smoking draws stares. None of the wine shops had women customers. Gender equality is not very visible here. At the Howrah Bridge, the area is clean but the surroundings are not, and toilets are located inconveniently. Women vendors here have to walk a distance to find one. What happens to their goods when they are away? In the flower market, we observed that women vendors do not use the toilet or drink water, preferring to munch puffed rice occasionally when hungry so that they do not need loo breaks.

We distinguished specific soundscapes and smellscapes too. In Esplanade, the busy commercial hub, many walkers felt continuously uncomfortable with men shouting and catcalling. Ronjinee, a postgraduate student of Sociology, noted how the type of music playing in different shops there showed the class-taste of the location; the soundscapes of Park Street and Esplanade were different. Aratrika, a Professor of Sociology, observed that our perception of better safety on Park Street was also due to the behaviour of hawkers who were more poised and less intrusive than in Esplanade and New Market.

The last step our walks involve are counter-mapping practices. Loosely based on Nancy Fraser’s idea of counter-publics, we have been able to reimagine/reconstruct infrastructure that can cater to caring and leisure needs of people as well as sustainable needs of the environment. These counter-maps are ways towards re-imagining an ‘un-gendered’ city, which respects the complexity and diversity in cities, and challenges the neo-liberal top-down urban planning and design.

This re-imagines symbolism in the city too – changing the overtly political landscapes into more secular ones, addressing issues of gentrification, ghettoisation and marginalisation. For this, we do interviews including of the walkers to make it more democratic, bottom-up and inclusive in nature. After all, to re-envision a feminist city, people need to speak for themselves.

Photo: Raka Bhattacharya

Photo: Raka Bhattacharya

While the Gender Community Walks were aimed at exploring known areas through the gender lens and reflecting upon our experiences, they have created a community and an awakening for many. A visually impaired participant experienced Kolkata more through smell. The walks are also a safe space for everyone to question one’s gender, challenge stereotypes, and be what you want to be.

We use these walks as an opportunity to reimagine the city, assert our rights, and underscore that safety does not mean restrictions on women but a safe city experience. Induja, a researcher, told me, “The walks have helped me think, they have also created safe spaces to share stories of intimate vulnerabilities.” We dwell on civic responsibility too. As Adrika, a teacher, mentioned, we must create a sense of belonging to build a gender-just and equitable city that ensures safety, comfort and a space for all.

I plan to approach policy makers with the suggestions that people give to me when we complete 10 walks. While policy changes are important, mindset changes are too. As Manasi, a communications professional told me, “A basic consciousness must be present in the minds of those in power to build cities that cater to all. These walks are a good source of generating such consciousness.”

Srestha Chatterjee has graduated with a Master’s in Sociology and nurtures a specific interest in urban sociology at the intersection of gender and urban planning with a keen interest in participatory planning and collaborative design. She holds monthly Gender Community Walks as part of her Pilot Research Project which aims at enquiring into the aspect of developing Feminist Cities in the Global South through a participatory, decolonised model of development.

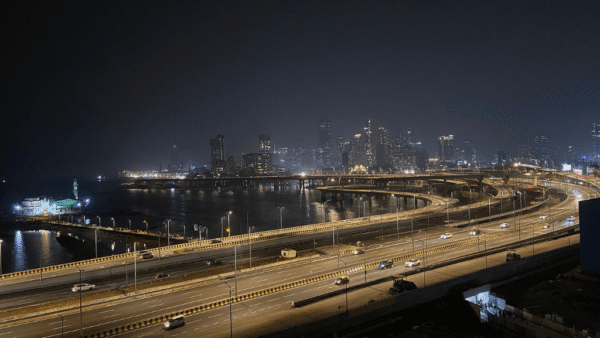

Cover photo: Wikimedia Commons