How often does one pause to notice where we walk? Pavements, or footpaths, are either invisible because vehicles are parked right on or beside them, inconvenient because they are uneven or too high, or have too many openings that require pedestrians to do minor acrobatics. Obstructions like open manhole covers and parked vehicles complicate this further. The presence of vendors or hawkers, though legitimate, is seen as an impediment. A walk then feels like an endurance game of hop, skip and jump – everything but actually walking.

The walkability index for India’s cities makes sense only when there are footpaths to walk on throughout cities, the construction of footpaths is guided by local policies but may be independent of the relatively comprehensive guidelines laid down by the Indian Roads Congress, the competing claims by pedestrians and vendors to footpaths is hardly that. Here are our deep-dive explanations.

How do Indian cities fare on the walkability index, especially when compared to international cities?

A survey by Clean Air Initiative in 2011 examined India’s cities for clean and wide footpaths, low traffic volume on road, obstacle-free footpaths, increased crossing junctions, effective street lighting, and easy access for disabled persons collectively called the Walkability Index. Chandigarh scored the highest on the index with 0.91 while the national average in India was 0.52. Delhi and Ahmedabad followed with index scores of 0.87 and 0.85 respectively.

What should be of concern are the cities that came at the lower end. In 2011, cities such as Shimla, Gangtok, Panaji, and Hubli-Dharwad scored a low of 0.22, 0.3, 0.32 and 0.39 respectively. The report pointed out that the Clean Air Assessment does not include a qualitative assessment of pedestrian facilities like walkway width and height, traffic, streetlights and safety.[1]

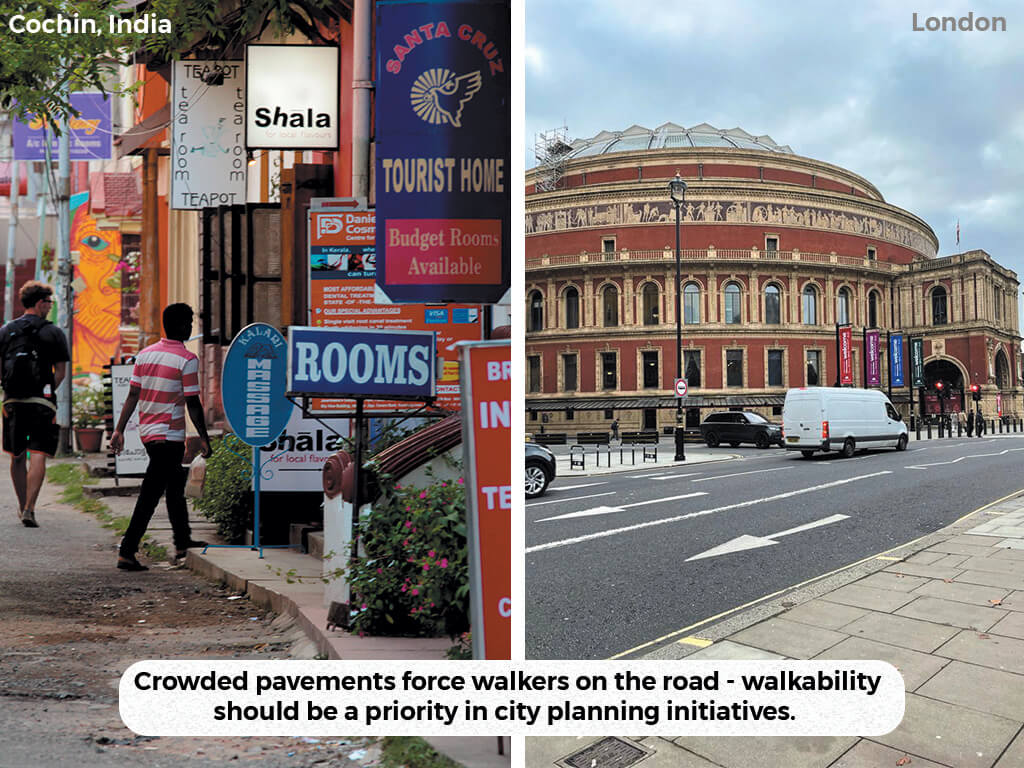

Among the most walkable cities in the world are London, Paris, Bogotá and Hong Kong, according to this report.[2] This is hardly a surprise given the emphasis and official attention given in these cities. London outranked almost 1,000 cities around the world on citizens’ proximity to car-free spaces, schools and healthcare, and the overall shortness of journeys in this study done by the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP) in 2020. The report also found that cities in the United States ranked particularly low on walkability, due to urban sprawl. Importantly, it pointed out that “making cities walkable was vital to improve health, cut climate-heating transport emissions and build stronger local communities and economies. However, they said very few cities overall gave pedestrians priority and were dominated by cars.”[3]

However, surveys and walkability indices fail to point out how certain localities in cities, Indian or international, are more pedestrian-friendly than others. Some areas within a city have better roads, wide footpaths and refuge areas with bus stops while other streets do not even have footpaths forcing people onto streets where walking becomes a life hazard. There can be no measure of walkability in the latter.

Are there policies and, if so, how are they implemented?

India’s major cities have policies for footpaths but have struggled to provide the infrastructure. Mumbai got its ‘Pedestrian First’ footpath policy only 10 years ago but even that has not been put into action which made the Bombay High Court, last February, to direct the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) to ensure walkable footpaths which are disabled-appropriate and elderly-friendly.[4] In April last year, the civic body was yet to conduct a survey of roads with a minimum width of nine metres so that footpaths could be constructed on both sides as part of the policy, and allotted a mere Rs 200 crore in the Rs 52,619-crore budget for 2023-24.[5]

The policy aims to ‘reduce pedestrian conflicts with vehicular traffic to minimum’. It advocates that pedestrians are not forced to walk in unsafe circumstances. that motorists need to respect the ‘right of pedestrians’, and that footpaths are provided consistently along the carriageway as a part of the ‘connected and continuous’ transportation system.[6] That the BMC only evolved the policy in 2014 and it is yet to be seen in action tells its own story. Meanwhile, pedestrian fatalities in Mumbai are as high as ever accounting for nearly 50 percent of all road fatalities.[7]

Chennai too released its non-motorised transport policy in 2014. Its goals included increasing the mode share for pedestrians and cyclists to at least 40 percent, reducing the number of pedestrians and cyclist fatalities to zero, ensuring that 80 percent of streets have footpaths and a right-of-way of 30 metres with a continuous 2-metre-wide cycle track that is unobstructed, segregated and continuous. The Greater Chennai Corporation set itself deadlines beginning 2018. Four years later, pedestrian deaths were still 35 percent of road fatalities.[8]

Photo: Shivani Dave

Way back in 2008, a draft Pedestrian Policy for Bengaluru highlighted the need for footpaths. In January 2023, it transpired in a survey by the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) and Janagraha, an NGO, that 67 percent people from 243 wards demanded that the civic body prioritise road infrastructure, footpaths, and drain maintenance. This tells the story of how the policy was implemented – or not – in 15 years.[9] The BBMP now says that footpaths will be developed in 2024 and the city will get 90 kilometres of footpaths.[10]

Meanwhile, pedestrians accounted for 33 percent of fatalities in road accidents – a number steadily rising.[11]

A recent Pune Municipal Corporation (PMC) report revealed that only 53 percent of roads have footpaths. This, even after the city has been building roads with footpaths on both sides as part of the Smart City Mission and the PMC has been organising ‘Pedestrians’ Day’ on December 11 for the last three years.[12]

In May 2023, Punjab became the first state in India to direct road-constructing agencies to build footpaths during road construction and expansion, recognising the ‘Right to Walk’ under Article 21 of the Constitution. This followed a petition for pedestrian and road safety filed in the Punjab and Haryana High Courts in 2010. In September 2023, Patiala was the first district to actually implement this policy.[13]

Uneven, narrow, hidden, and even nonexistent footpaths with broken ramps are a great cause for worry for even the able-bodied. For the disabled, children and the elderly, such footpaths are more challenging. Bollards being too close to each other make it difficult for people to pass through; wheelchairs or prams cannot even negotiate them.[14] [15]

In all, it appears that India’s cities did not evolve policies on footpaths for decades but having had some semblance of them in the last 10-15 years, they are not visibly implemented even as pedestrian fatalities are recorded every day. This is unacceptable and unpardonable.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

What are the guidelines in cities?

The Indian Roads Congress (IRC) in 2012 prepared a document with specific guidelines for pavements or footpaths. It details out what footpaths are, how they should be constructed, and lists everything from designs and specifications to locations and material. This document has been referred to by several municipal corporations across India. Here’s what it states:

- Footpaths are divided into three main zones, the frontage zone along the compound wall, the pedestrian zone for walking, and the furniture zone which has space for manholes, trees, benches and also vendors. The latter is important in India because most cities have vendors on footpaths.

- The width of footpaths depends on the land use of the area. Footpaths in residential areas need to have a clear minimum width of 1.8 metres, enough for two wheelchairs to pass by each other. In commercial areas, it is recommended that the pedestrian zone is at least 2.5 metres wide.

- The height of the kerb above the road or carriageway should not be more than 150 millimetres, footpaths must have flat walking surfaces, allow for proper drainage to prevent water stagnation, with design for guide tiles along the length to guide the visually impaired.

- Dedicated space should be provided for trees, away from the path of pedestrians, and for bulb outs at pedestrian crossings to reduce the distance walked on the road. Tabletop crossings, which are at the same height as the footpath at every 200 metres are recommended.

- To encourage uninterrupted people movement, footpaths should be continuous even at property entrances. The height of the footpath should be the same at the entrance to avoid water-logging. To allow for vehicular movement, vehicle ramps are recommended in the furniture zone which can also help reduce vehicle speed.

- Warning tiles on either side of the entrances to property zones helps to warn visually challenged pedestrians about possible vehicular movement. Additionally, installing bollards on footpaths can prevent vehicles being parked on them.

Hawker space in the guidelines

Clean footpaths with no activity on them may look aesthetic in pictures but are ‘dead’ spaces in reality; activity means safer walking spaces. The IRC, with or without inspiration from the noted urbanist Jane Jacobs’ idea of ‘eyes on the street’, provided for vendors without obstructing pedestrians. Accordingly, vending spaces should be in the furniture zone or on bulb outs in the parking lane, leaving space for walkers in the pedestrian zone. This also suits the vendors since they tend to look for spaces under trees or near bus stops.

In many cities, bus stops tend to be on footpaths forcing pedestrians to step off for that distance. To ensure seamless movement, the IRC recommends that bus stops be placed in the furniture zone on wider footpaths, leaving at least 1.8 metre width in the pedestrian zone. And in areas with parking lanes, bus stops are recommended on bulbouts in the parking lane so that people at the bus stop do not have to wait on the road, endangering their lives; they can board the bus from the kerb.

The IRC recognised the need for parking and laid down that parallel parking, where possible, not only saves space. Importantly, it emphasised that parking is a ‘flexible street element’ which should be provided only where there is sufficient space and adequate provisions for pedestrian movement.

Photo: Shivani Dave

The IRC recommends raised or elevated tabletop crossings that are at least 3 metres wide located every 200 metres, with ramps for vehicles to reduce vehicle speeds, and also emphasises pedestrians’ safety. At intersections, the IRC suggests that the design raises the intersection to the level of the footpath but is made in a different material. This ensures that vehicles slow down and realise that they are in a shared space with people. In areas without raised crossings, the footpath should be at the road level with its incline not steeper than 1:10.

Pedestrian refuge areas on streets, which seem like a luxury in India’s cities, are also recommended because they give time and space to people to reorient themselves at road crossings, especially if it involves two lanes. The refuge areas need to accommodate a large volume of people and wheelchairs.

What makes for good walkability in cities?

Walkability in cities is important not only for work but also for health and environmental reasons. A study on walking and people’s health, sustainability and livability concluded that ‘Improving walkability not only contributes to more efficient use of energy but also adds vibrancy by improving resident, tourist, and visitor access.’[16]

A World Health Organisation (WHO) study found that investments in policies that promote safe walking and cycling policies play an important role in shaping people’s health, mitigating climate change and improving the environment.[17] The problems of emissions of greenhouse gases, noise, injuries, limited use of public space and opportunities for physical activity can all be addressed by policies that promote walking and cycling in cities.

To realise this, the WHO lists out recommendations which include safe walking and cycling infrastructure to promote active travel; redesigning urban spaces to bring amenities within walking distances; green spaces, parks and trails as forms of urban rejuvenation; and disincentivising driving to promote walking and public transport along with making schools accessible to children on foot and bicycles.

Beyond pedestrian policies, it suggests that countries should develop national cycling and walking plans, secure resources, and allocate responsibilities to implement these plans.[18] India’s cities are far away from this, but should head in that direction.

Jashvitha Dhagey is a multimedia journalist and researcher. A recipient of the Laadli Media Award 2023, she observes and chronicles the multiple interactions between people, between people and power, and society and media. She developed a deep interest in the way cities function, watching Mumbai at work. She holds a post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic.

Cover photo: Motorists share the footpath with pedestrians in Pune. Credit: Jashvitha Dhagey