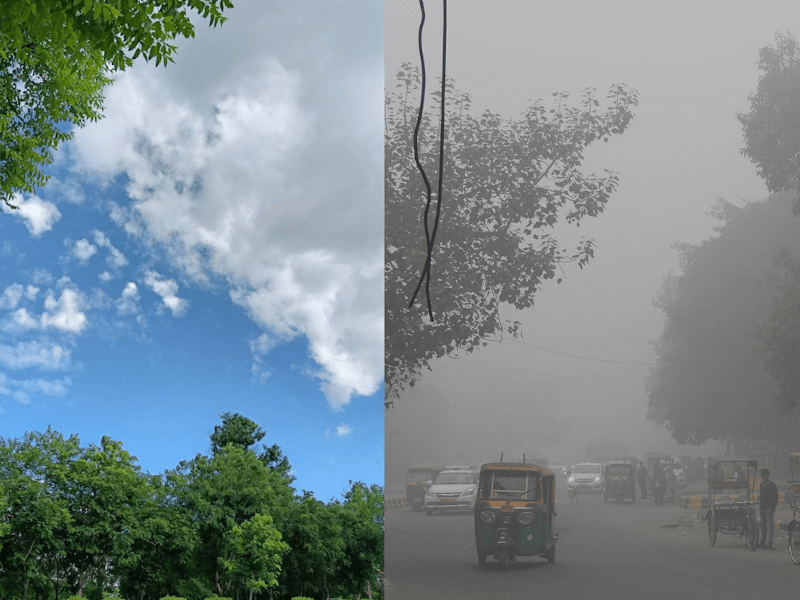

Delhi has routinely topped the charts in being one of the most polluted cities[1] in India as well as across the world.[2] The air quality in India’s national capital plummets every winter. Stubble burning in neighbouring Punjab and firecrackers during Diwali are held responsible. But this masks a fundamental truth – Delhi’s air pollution is not a winter-specific problem but an all year round[3] phenomenon.

This is not to say that Delhi’s governments have not addressed the issue over the years. Delhi’s transport, a major contributor, operates under some of the strictest[4] vehicle emission standards and fuel quality norms in the country. Cleaner fuels such as CNG were introduced years ago, the Bharat Stage VI emission standards were rolled out, metro network expanded and the city is now moving towards replacing CNG buses with electric ones.[5] Pollution-specific measures, myopic or otherwise, have been put in place but the city records a new pollution[6] low every year.

This is because the city’s natural defenses have been steadily weakened too. While anti-pollution short-term and long-term measures are being adopted – with differing degrees of commitment and success – what has been missing in the discussion are the interconnections and relationships with what lies outside the national capital. The state of the Aravalli hills and range, for example. Air and water, as all natural elements, follow no administrative boundaries.

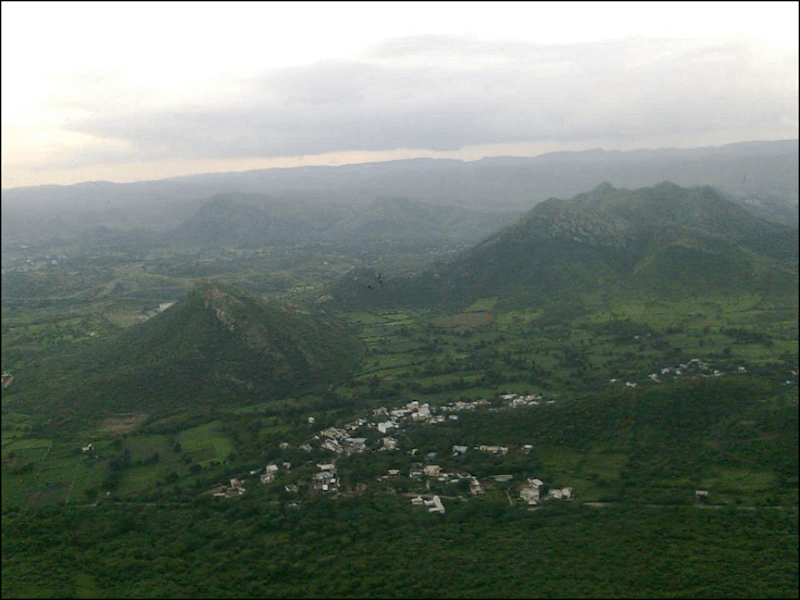

Stretching across Rajasthan, Haryana, and parts of Delhi NCR, the Aravalli hills are one of the oldest mountain systems in the world. Though low and fragmented, the range has historically played a crucial ecological role[7] in slowing desert dust from the west, influencing local wind patterns, and acting as a buffer against the unchecked movement of particulate matter into Indo-Gangetic Plains. While silent, these cumulative processes have helped clear Delhi’s air to some extent but it’s not an interconnection always honoured.

Photos: Ankita Dhar Karmakar/ Wikimedia Commons

That’s why the threats to the integrity of the Aravallis matter far beyond Rajasthan alone and questions of mining. The recent push to redefine the range risks dismantling the centuries-old ecological systems that influence air quality, groundwater recharge, and climate resilience across India’s northwestern region including Delhi. Environmentalists warn that weakening these natural barriers could intensify dust inflow and raise pollution levels in the already saturated airshed in Delhi. Its pollution is already a public health emergency that threatens 17,000 lives[8] every year. Studies show that now this pollution is fuelling anti-biotic resistant superbugs[9] in the air. Delhi’s need to clean its air is urgent; so is the need to recognise the larger ecological interconnections.

What losing the Aravallis mean

The new Supreme Court-monitored definition exposes nearly 50 percent[10] of the Aravallis to commerce, especially mining. This is important because, between 1975 to 2019, as this 2022 study[11] notes, about 8 percent of the Aravalli hills were lost to mining and urban expansion; if this trend continued, by 2059, as much as 22 percent of the Aravalli system could vanish. This was projected before the redefinition of the ranges. The redefinition, will in all likelihood, accelerate this loss, say environmentalists.

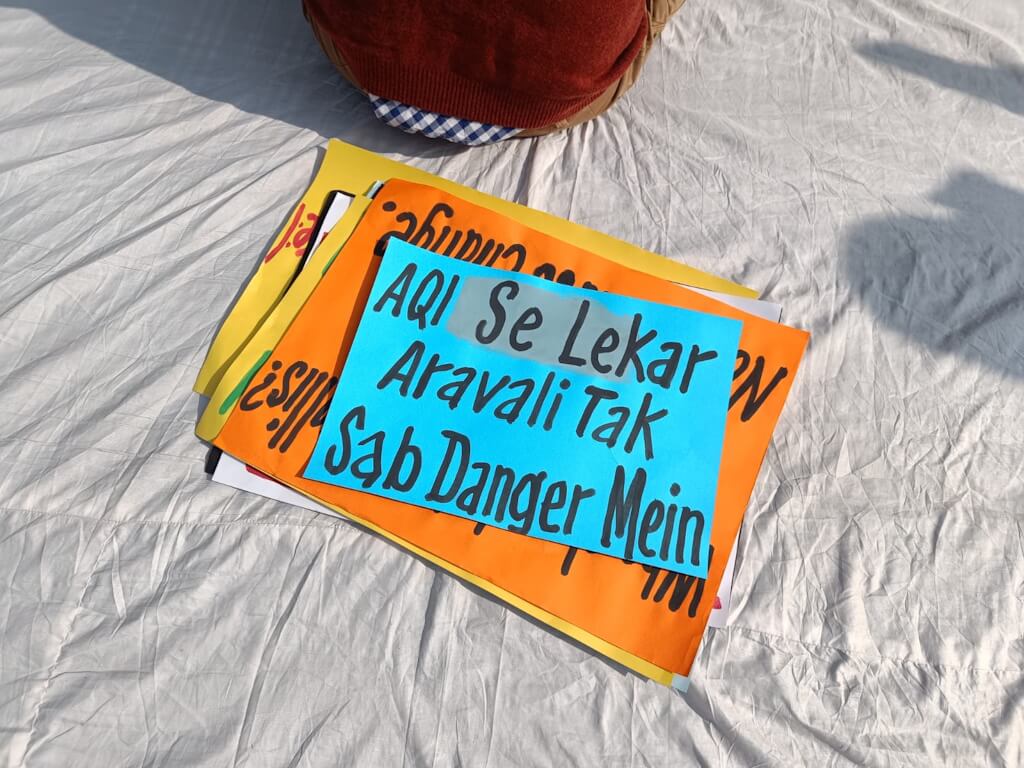

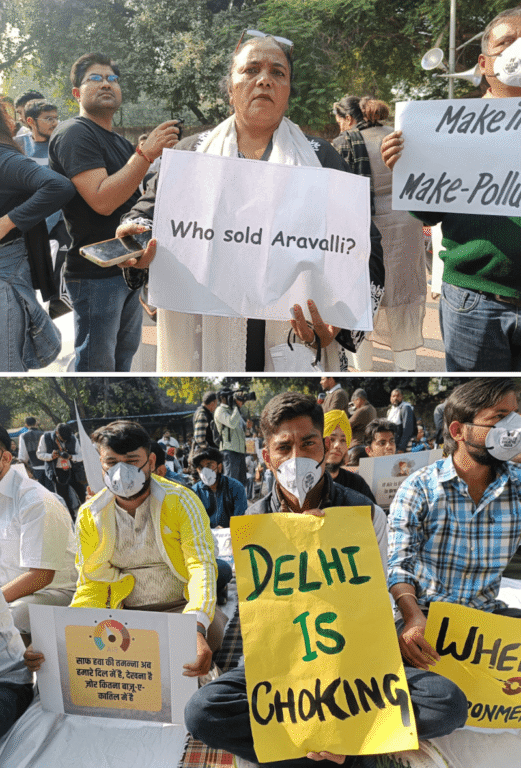

The Congress[12] and the AAP[13] have warned that the redefinition of the Aravallis will open the hills to not just mining but unchecked expansion, cause irreversible harm, and worsen Delhi’s air quality. Residents of Gurugram who form a part of Aravalli Bachao Citizens’ Movement,[14] a seven-year old citizen-led-group in Delhi-NCR, echo this. Anuradha P Dhawan says, “This idea of development has not given us clean air, clean water or good health. The Aravallis are climate regulators, vital carbon sinks. Where these hills have been degraded, you can already see the consequences. Dark clouds hang over those areas because the hills are no longer able to do the work they once did.”

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Aditi, student union president of JNU, which sits inside the Aravalli ranges, was part of the recent protests[15] against the redefinition of the Aravallis. She too fears that the redefinition will intensify the air pollution. “In 2010, the Supreme Court had rejected[16] the FSI’s 100-metre definition of the Aravallis replacing it with the three-degree slope rule. Today, we see the SC favouring it. Thankfully, there is a stay now,” she explains.

The Aravallis help in blocking the dust blowing from the Thar desert from reaching parts of Delhi-NCR, and therefore, help to control air pollution. “In all likelihood, if mining is permitted, there will be an impact on how much dust reaches Delhi and surrounding regions,” says Bhargav Krishnan, convenor of Sustainable Futures Collaborative.

Dust pollution[17] also remains a key contributor to Delhi’s air pollution. Every year, pre-monsoon dust[18] from the Thar desert reaches the capital, enveloping parts of the city in a dust storm. It also critically shoots up pollution[19] levels. Losing the hills will lead to a loss of this barrier. Another danger is that increased mining activity, involving crushing and grinding, will further add to the overall pollution load in Delhi-NCR.

The way ahead, say members of the Aravalli Bachao Citizens Movement, is to declare the Aravallis a UNESCO Biosphere, impose a complete halt on all mining in the hills, stop construction activities, and shut down coal-fired power plants that do not meet international clean emissions standards.

However, it is not just the risk of losing Aravallis that should worry Delhi-NCR. The area is steadily losing wetlands, floodplains and green buffers – including systems such as Najafgarh Jheel and the Sahibi river corridor. Nidhi Batra, founder of Sehreeti Development Practices, calls this a neglect of nature-based solutions. “These ecosystems act as carbon sinks, dust filters and temperature regulators. Their degradation has weakened the city’s natural ability to absorb pollution and heat, increasing vulnerability to both air pollution and climate extremes,” she explains.

The steps so far and the need to go beyond

- Tackling quick fixes, weak enforcement

Of course, recognising and respecting the interconnections does not mean going easy with anti-pollution measures. Delhi-NCR has them; the implementation is in question. In 2019, when the union government introduced the National Clean Air Programme (NCAP), it promised to reduce two major pollutants: PM10 and PM2.5. However, since 2022 the NCAP’s focus has shifted[20] to PM10, more specifically dust suppression. Not only this, in 2025, the centre’s decision[21] to reduce focus from biomass and municipal solid waste burning – major contributors to PM2.5 – and instead prioritise dust mitigation and vehicular emissions continues the trend.

While PM10 coarse particles are easier to control and show quicker results, PM2.5 are the finer particulate matter that penetrates deep into the lungs and bloodstream, and is responsible for severe health impacts. This shift is also visible on the ground. To suppress dust, there’s water sprinkling, smog towers, and even the failed cloud seeding project.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Shahzad Gani, Assistant Professor at the Centre for Atmospheric Sciences at the Indian Institute of Technology (Delhi) argues that these measures create an illusion of action without addressing the sources of pollution: “You see trucks spraying water everywhere in Delhi but you cannot wash the atmosphere. Even rain only helps for a day or two. It’s simply a waste of water.” Weak enforcement further undermines the existing regulations. Manoj Kumar, researcher at Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), notes that poor implementation allows polluters to operate with little consequence: “Emission norms exist but implementation is weak. A 20-year old vehicle can pass a PUC test without even starting the engine.”

Emergency responses like the Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP) are activated only when pollution levels become severe. It functions as a crisis management tool rather than a preventive framework, says Pratima Singh, Director of Air Pollution and Waste Management at iForest,[22] an independent non-profit for environmental research and innovation. She warns that there is little clarity on whether these shutdowns and restrictions meaningfully reduce pollution levels or merely offer temporary relief.

- Tacking all sources

To reduce pollution in a meaningful way, scientists and experts argue that policies must first confront the sources of emissions. PM2.5 is largely produced through combustion. Kumar and Gani both explain that emissions from vehicles, coal based power plants, industries, waste burning and household fuels are the major sources. As long as these remain unchecked, dust suppression offers little more than temporary relief.

Shifting to cleaner fuels is a meaningful intervention. Government schemes like the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana, which replaced biomass fuels with LPG cylinders, showed that targeted fuel transitions can cut pollution at source. However, any hike[23] in cylinder prices turns people back to burning woodfire. But similar transitions in transport and industry, including the adoption of electric vehicles, and tighter controls on fossil fuel use, are critical.

- Tackling Airsheds

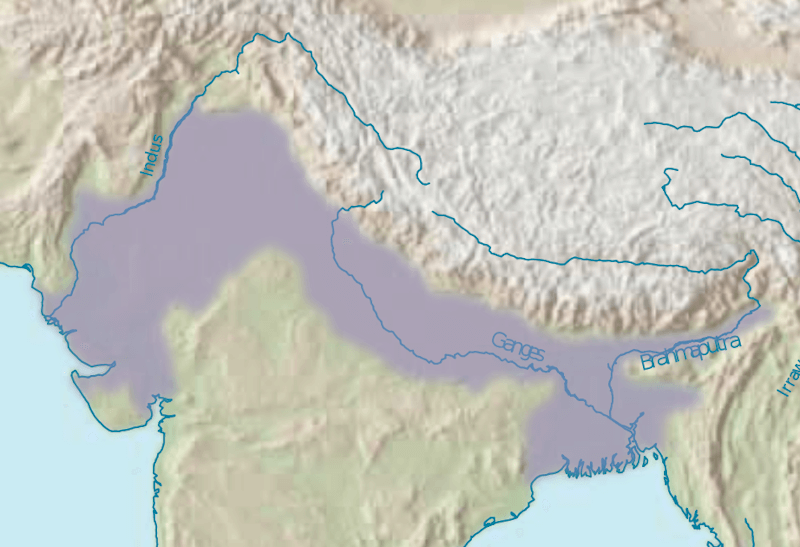

Air pollution does not stop at city or state borders; the larger zone of shared air movement is called an airshed. So, Delhi’s toxic air cannot be understood or cleaned only within the city’s administrative boundaries. Emissions in neighbouring states like Punjab, Haryana, parts of Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh all feed into the shared air system. This is aggravated due to the unfavourable meteorology in the Indo-Gangetic Plains with the Himalayas contributing to the trapping of pollutants, explains Gani.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

This regional spread is especially significant with large industrial sources such as thermal power plants that can impact air quality from hundreds of kilometres away making pollution transboundary. “That is why air pollution has to be addressed at an airshed level, not just city or state boundaries,” says Kumar. This is also why the Aravallis matter to Delhi, to see the range from an anthropocentric view.

- Moving away from a car-centric city

Research[24] shows that vehicular emissions are one of the main causes of Delhi’s pollution. According to a reply[25] in the Lok Sabha by Nitin Gadkari, Union Roads Transport and Highways Minister, Delhi has more than 1.5 crore registered cars, 52 percent of which are private vehicles – almost equal to the combined total across Mumbai, Kolkata and Chennai. More cars mean more vehicular emissions.

The solution? More public transport. Sarika Panda Bhatt, Director at Nagarro and Founder Trustee of Raahgiri Foundation which champions public transport, says that expanding roads without expanding public transport has locked Delhi into rising vehicle dependence.

As of July 2025, Delhi’s bus fleet plummeted[26] to 5,853. With a population of 45 lakh, the city needs at least double that, says Panda. Walkability should be encouraged while car ownership is discouraged, she adds. “We need to price parking and congestion. Singapore, London, and Paris have done this. In Singapore, you pay almost the same amount for parking rights as the price of a car. That’s how they discourage car ownership. Even the rich don’t own cars because public transport is strong and car ownership so difficult. In India, despite being a poorer country, our aspiration is centred around buying vehicles because there is no alternative,” explains Panda.

Imagining clean air differently

As the debate on Delhi’s air pollution circles around numbers, sources, and seasonal fixes, people in the domain offer a different argument: Air cannot be treated as an isolated environmental problem. It is produced by the way cities are planned, how people move through them, what forms of infrastructure are prioritised, and what natural systems are recognised and allowed to survive. This is the integrated ecological approach – mostly lacking in Delhi’s clean air debates.

How people experience pollution is also different. “Workers do not have formal compensation for their work loss so they cannot afford to not work. When the government implements GRAP asking people to stay indoors, use purifiers and masks, these are unaffordable for the working class,” notes Avinash Chanchal, Deputy Program Director, Greenpeace South Asia.

Photos: Ankita Dhar Karmakar

“If you fix mobility, you fix air pollution, road safety, women’s safety, public health, and even jobs. Good streets reduce dust, heat, and pollution. Everything is interconnected,” says Panda. For Gani, air pollution is about how urban life itself is organised. “It should be placed in the broader context of how different people experience cities. It is not just about PM10 or PM2.5, it is not only a technical or scientific issue. It is about urban life and governance, and how we choose to design and inhabit our cities.”

In Delhi-NCR, this also means safeguarding the Aravallis. To imagine cleaner air is to imagine cities that move less by cars and more by people, that rely not just on machines but on natural landscapes, and that treat nature as an ally.

Ankita Dhar Karmakar, Multimedia Journalist and Social Media in-charge in Question of Cities, has reported and written at the intersection of gender, cities, and human rights, among other themes. Her work has been featured in several digital publications, national and international. She is the recipient of the 4th South Asia Laadli Media & Advertising Award For Gender Sensitivity and the 14th Laadli Media & Advertising Award For Gender Sensitivity. She holds a Master’s degree in English Literature from Ambedkar University, New Delhi.

Cover photo: Ankita Dhar Karmakar