One of the major impacts of development in cities across India has been the loss of forests, hills, water bodies and other elements of natural ecology. This means different things in cities like Bengaluru’s lakes have disappeared, Mumbai’s wetlands and trees are under attack, and Jaipur’s residents are rising up to protect Dol ka Badh forest. The popular narrative is land is needed for development (construction), so ecology has to be sacrificed – a binary. How do you see this?

I think ecology is one of the least valued types of land use in the city. It is definitely and massively changing. Wetlands and water bodies are the most visibly affected but so is everything else. It’s the empty plot in your neighbourhood which used to have a certain kind of ecology, the trees on the road side in any city, everything has changed. It’s sadly unquantified and invisible because the land on which the ecology sits is considered as available space to be used because it’s ‘going to waste,’ something productive can be done with it, productive in economic terms. So, I think there’s something very fundamental in the way we value or devalue ecology when we decide on land use.

If you look at the old inscriptions of Bengaluru from the 11th or 12th or 13th century AD – I have written about this – many of them talk about a village and describe its boundary in terms of natural areas: dry land, wetlands, lakes below and trees above. These are beautiful descriptions of land. Such a three-dimensional imagination has been completely lost now. The moment people buy a plot of land, because it’s so expensive, the first thing they do is fill up the wells and cut the trees so they can build on them. That description of a village which talks about water, dry land, wells and orchards, and temples is a telling one. We have lost that imagination.

Our imagination of land has been flattened out.

Yes, and it is physically also flattened out too. In the Bengaluru I remember, and this is true of many Indian cities, there used to be undulating terrain. Now, hills have been blasted to the ground, the marshy areas and wetlands filled in to increase their height. So, cities are leveled or over-leveled.

There’s an argument that land use has to be maximised because cities are growing, so what if a few trees go. How do you deal with such arguments which dominate the discourse now?

There are two things wrong with this argument. Firstly, if you look at the earlier cities, there is, of course, the colonial heritage which is problematic in its own way but even the non-colonial dense cities kept space for natural water systems, trees and orchards because they were a part of the city, they supported the city. What we fashionably call a circular economy was naturally present. The city relied on the water and food grown in its neighbourhood, so took care of it.

But, secondly, as human beings, we tend to think linear and not understand tipping points. While it is true that, at a certain level, you can see growth in terms of infrastructure and consumption even at the expense of ecology, eventually there will be a deterioration in people’s well-being. The tipping point is not always seen. The ecology in cities supports us by being an invisible buffer but gets eroded as cities grow, and reach the tipping point. Many Indian cities are running out of water, many are flooding quickly. Even Guwahati is flooding with just a few centimetres of rain – something one would not expect in a city with its fields which can manage water. You don’t expect cities like Chennai to run out of water because it has marshland, lakes, wetlands and mangroves which are natural sponges but Chennai is running dry.

So, there is a natural buffer. What’s the tipping point at which we lose it due to development? What do we breathe without the trees and their natural air filtration? How much can the smoke scrubber technology help to scrub the air clean for us? In the early stages of urban growth, perhaps it was fine because we were in the linear phase. Now, we have eroded the buffer, we are reaching the tipping point and not recognising it because we are still thinking linear. The tipping point is a warning.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

When you say ‘we’ are reaching a tipping point and not recognising it, it’s important to draw the distinction between people and government. People are realising, collectivising, acting to protect the ecology in cities while governments and certain policy makers don’t seem to.

Governments and policy makers don’t want to change the paradigm or it may be economically profitable in the short term and they are thinking about short-term maximisation. What do they get out of long-term thinking? Prioritising ecology is perhaps not visible to them.

So, even if it doesn’t appear to be, isn’t the question of land use and ecology ultimately a political one?

Exactly, it is an absolutely political question. If you look at the laws or at least the policies for how much per capita green space there is, how the valleys and hilltops need to be protected, how drainage areas and the wetlands cannot be converted to any form of land use, there are rules and policies. There are at least guidelines. They are actually effective but they are violated with increasing impunity because the argument is always that land is scarce. So, the pressures are getting more and more. If you have a national park in the city, the thinking is it is land available for development – why justify keeping it just for ecology? That’s why our parks get eroded, and their buffer zones steadily reduced. Ecology is de-prioritised.

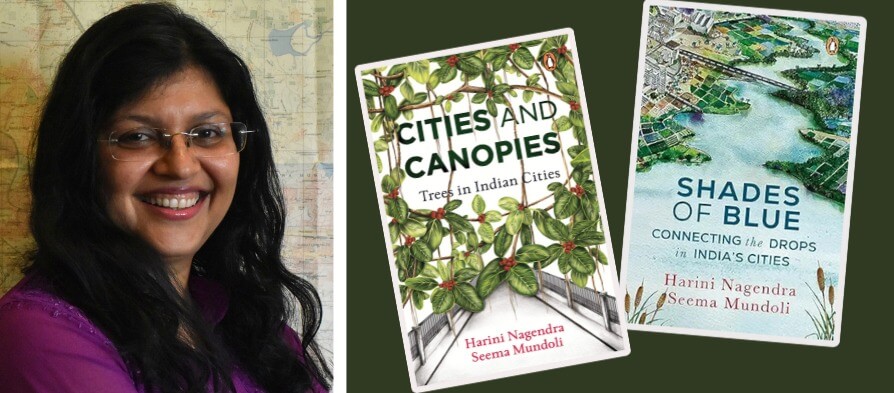

In both the books you co-authored, on trees and on water in cities, you brought out the complex web of life they support. When ecology is diminished or lost, so is this biodiversity despite laws to protect it. In the land use-ecology question, how can other life forms be made important enough?

I think the ‘we’ is an important point that you raised. Which is the ‘we’, right? It’s the regular citizens, I think, so many people go to a lake or a park or walk on the beach and see a bird, a butterfly, a turtle, specific fish, dolphins and are moved by it. I find a lot of people increasingly becoming aware of things like foraging in cities, going to places of nature and asking what they can do. Then, there are groups looking at pollinators; pollination is important for many people growing vegetables on rooftops, for instance. People are protecting roosting sites or nests on trees.

Ecology can sometimes be a vague term but you see people care about biodiversity. But getting policy makers to look at the importance of ecology for biodiversity becomes really hard. In my experience, they only value ecology if you tell them about financial benefits or health benefits or ecosystem services, even physical and mental health. It’s a bit of a stretch but they are willing to do it. But if you emphasise the value of things like biodiversity, they start looking at you like you are taking it to an extreme.

Photo: QoC File

But it’s important that a few involved people talk about biodiversity.

Of course, yes. There are nature clubs, even apps like eBird or INAT or Merlin where you can look at a bird, figure it out, put it on a list, go for walks with a group. Our M.Sc and B.Sc students at Azim Premji University have started going for biodiversity walks around the campus. They started with birds, then realised ecology is about much more than birds, so they look at whatever they find – insects, lizards, frogs, snakes etc. They upload the birds on eBird and make a checklist for other species. Now they have gained skills to identify whatever biodiversity exists in those patches. It’s also a great stress buster. This is one example; you find so many groups across every city now doing something like this. There were a few individual naturalists earlier, now there are so many such groups mushrooming. So, I think it’s a question of who the ‘we’ is. We must keep at it.

It’s also a question about how ecology and the entire ecosystem in cities is seen, especially by planners and governments, and what needs to be protected. The approach, as you said, seems to be that profits matter and perhaps people do, but lakes, ridges, forests and wetlands don’t. How do we change this?

Climate change is something that policymakers are now paying attention to, especially in cities, and with climate action plans, I feel there’s an opportunity to at least try. It’s not going to happen very easily but, at least, policy makers are valuing nature in cities. The larger question is how the different parts can be brought together. There are different government organisations or departments, one for sewage and sanitation, another for bore wells, another for electricity, then there’s the groundwater department, one handling lakes, and the revenue department. So, just to regulate the uncontrolled exploitation of groundwater is a challenge.

This is systemic failure but the system responds when there is mass public movement or public demand for something. So really, at one level, you need the education not only in schools and colleges but education of the public on nature awareness, and in a sustained way. But this education and awareness have to be political, not in the sense of joining a political party but in the sense of engaging with elected representatives and governments, using the collective will of people to demand certain things. Wherever we have seen change, it has been because of people’s demands that were coalition-based.

For instance, Bengaluru’s lakes or Save Aarey or in South Delhi, the criticism leveled is that these movements have not talked adequately across class and interest groups. It’s not easy to do that; the fact that they’ve come together to organise in a sustained way is incredible and I don’t think pejoratively calling them bourgeois environmentalists is fair. It is not easy to build coalitions but we need to do that across diverse classes and interest groups because that’s the only way political movements will work. So, what I mean is that even when we value nature, we don’t understand the importance of being politically organised, to claim our rights or to argue for the rights of nature.

Photo: QoC file

That’s right. Cities have old residents, women, poor people with local knowledge of a place, its ecology which appears in their stories or remembrances, even folklore. Somehow, this local knowledge doesn’t reflect in conservation plans, if there are plans. Like in Dharali, the locals said they knew how the river behaves, where it gets angry. How can this knowledge, to the extent it exists in cities, be brought into conservation plans, movements, or collectives?

One of the proposals that a group of us at Azim Premji University put together some years ago was an idea for an urban employment guarantee scheme – as part of which, we focused on nature restoration or improvement of the ecology. We had suggested that every ward have representatives who were ecology data collectors, so to speak. They could be students, trainees, young people rotating every two years. If you are an environmental science person, you collect that kind of data; if you are a history or sociology graduate, then perhaps you talk to the older residents and map their traditional knowledge.

Like in Dharali, Uttarakhand, in Bengaluru when we were restoring the Kaikondrahalli Lake on Sarjapur Road, the municipality was not sure that a lake of this size would fill with water because it’s urbanised all around. We spoke to the groundwater control board who were confident it would fill. So, the municipality began the restoration. It started raining but the lake was not filling with water. Then, we talked to the local community, the original village residents, who showed us that water was being blocked in the farmland behind the lake – there were traditional water channels, but they were not officially marked on the maps, which means they were not restored. Then, civic officials talked to the landowner, he agreed to let them clear the channels, and within half a day, water came into the lake.

How do we know about such small but important details unless we talk to the local people? For this, we need a system. I would think that, for every locality, we need an information gathering system of the local ecology there, which is not done only at the time of some restoration. Because if we rely solely on project reports for restoration, these project documents are almost always designed by consultants who are not from the local area. We need a way for local data collection to be embedded in the system and students are the best way; they are in college for two years, four years, they can talk to local residents and get the information. People can then use it to meet as a committee with elected representatives or a bureaucrat. And this becomes a weekly or monthly event which feeds into planning on a regular basis.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Our cities have land use or development plans, now climate plans and heat action plans but not a comprehensive ecology map. In its absence, the cumulative impact of what is lost or compromised, does not come through. We see a few trees here gone, a lake there landfilled, but the cumulative impact remains vague because we don’t have one map which shows what ecology was lost in say 10 years. Do you think every city should work towards a comprehensive ecology map?

I think so, very much so. Also, it’s possible now because we have drones and AI, we can do high-resolution remote sensing, and it doesn’t require armies of people. We should be able to have open-source maps that governments commission and actually put up online. It’s not correct for private institutions to do this alone, because of privacy reasons and legal issues – the government needs to be a core actor. But now, with remote sensing technology – trees in an area, land covered by marshes, open spaces, how accessible a park is, natural features of a place – all this can be in the map.

We need publicly available information and maps, done using public resources because that makes it legitimate. It’s not that much of an investment now, it can be done, and we should all push for it.

Cover Photo: Kaikondrahalli Lake, Bengaluru; Credit: Wikimedia Commons