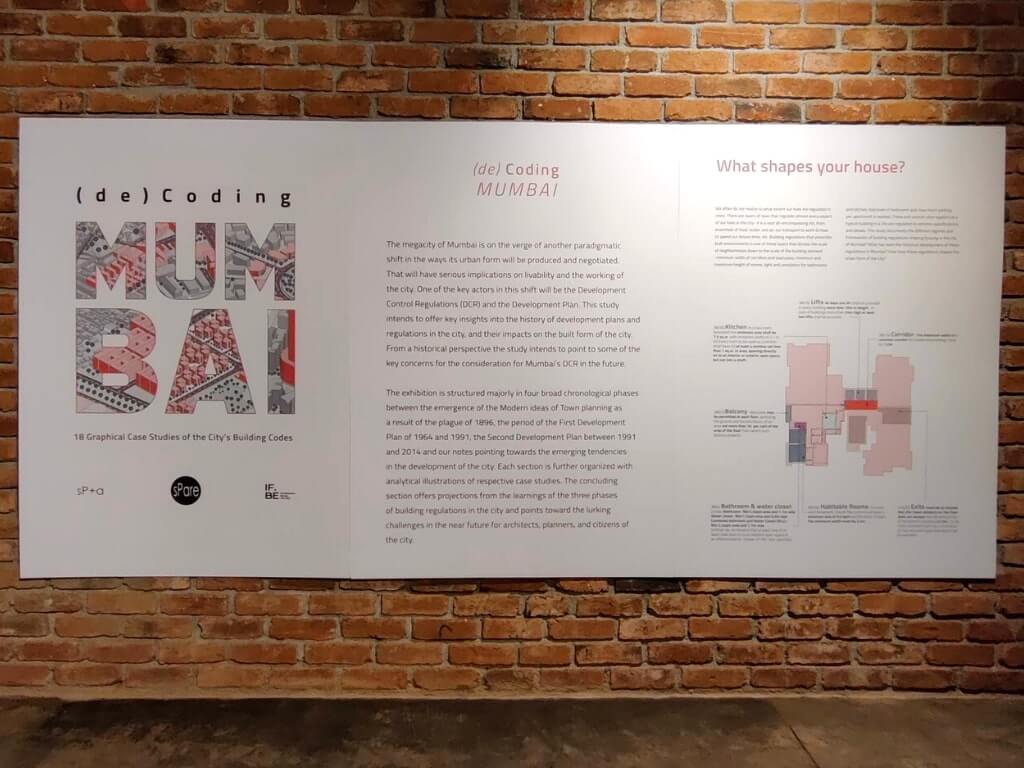

“We often do not realise to what extent our lives are regulated in cities,” read a plaque at the start of “(de)Coding Mumbai”, an exhibition by Mumbai-based architect Sameep Padora on how the building regulations and their change over the century had left an impact on the urban fabric of Mumbai. The exhibition, which traced the trajectory of housing in the city as an outcome of the laws and regulations enforced by the state from time to time, culminated in a panel discussion which examined the future of housing in a city where it is a coveted aspiration for millions, a city in which housing represents both the contrasts and the inequality in the urban fabric.

Following that sentence on the plaque were a list of decisions which have been taken for Mumbai’s residents by those in power. Decisions such as how we get our food, water and air, what are our forms of transport and places of work, what are our spaces of recreation, and so on. The size of our homes and rooms in them, the lengths of corridors and width of balconies, the shape and spread of housing complexes and societies, all of which shape the urban fabric, are regulated by specifications of the built form laid down as Development Control Regulations (DCR).

Padora’s plaques, two in all, mounted on large frames that draw the eye to examine known parts of the city closely, make the connection between the built form and the regulations which governed the structures, and thereby the urban form. Seen in a continuum, they illustrate the timeline of urban development in Mumbai since 1896 when the first building codes were mandated in the post-plague years and metamorphosed into the DCR as we know it today. The timeline that Padora draws makes it abundantly clear that the DCR – and its previous avatars – has been a transactional tool in the hands of governments and administrations, to determine what will be built and where, how it will be built and for whom. In that sense, Padora details out for the lay viewers the open secret about the city: Rules about land and property should be about the city including its poorest but remain a tool in the hands of the powerful for their benefit.

Padora, an award-winning architect with a post-graduate degree from the Graduate School of Design at Harvard University, is the director of sPare, a research initiative looking at urbanisation and architecture in India, and the principal architect and founder of Mumbai-based studio Sameep Padora & Associates, or sP+a. The maiden project of sPare to document and analyse historic housing types in Mumbai resulted in a travelling exhibition and a book published by the Urban Design Research Institute, which in turn coalesced to “(de)Coding Mumbai” (see his interview).

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

An insight into how Mumbai was built

The exhibition with 18 case studies, mounted at IFBE in Ballard Estate in June this year, was a study which documented how the different governments and regimes brought in different frameworks of building regulations which, in turn, determined the built form, specifically housing, in Mumbai. “(de)Coding Mumbai” also saw walk-throughs, lectures, panel discussions and workshops on the theme to get people interested enough to debate the idea of housing, the laws that govern the sector, bye-laws, different stakeholders, their aspirations and engagements with the city. It was a conversation long overdue in a city where housing of all hues and prices is at a premium.

Fittingly, Padora had mounted the exhibition in a run-down place which used to be old Bombay’s ice factory. The 18 case studies, spanning across a timeline of 1896 to the present, revealed the less-discussed aspects of the city’s Development Plans, building codes, and rules which govern the housing sector in the city. In order to “decode” Mumbai, Padora and his team studied houses and residents through Development Plans, and brought out the impact of building codes and DCR on who gets what built form in the city and how the city eventually looks.

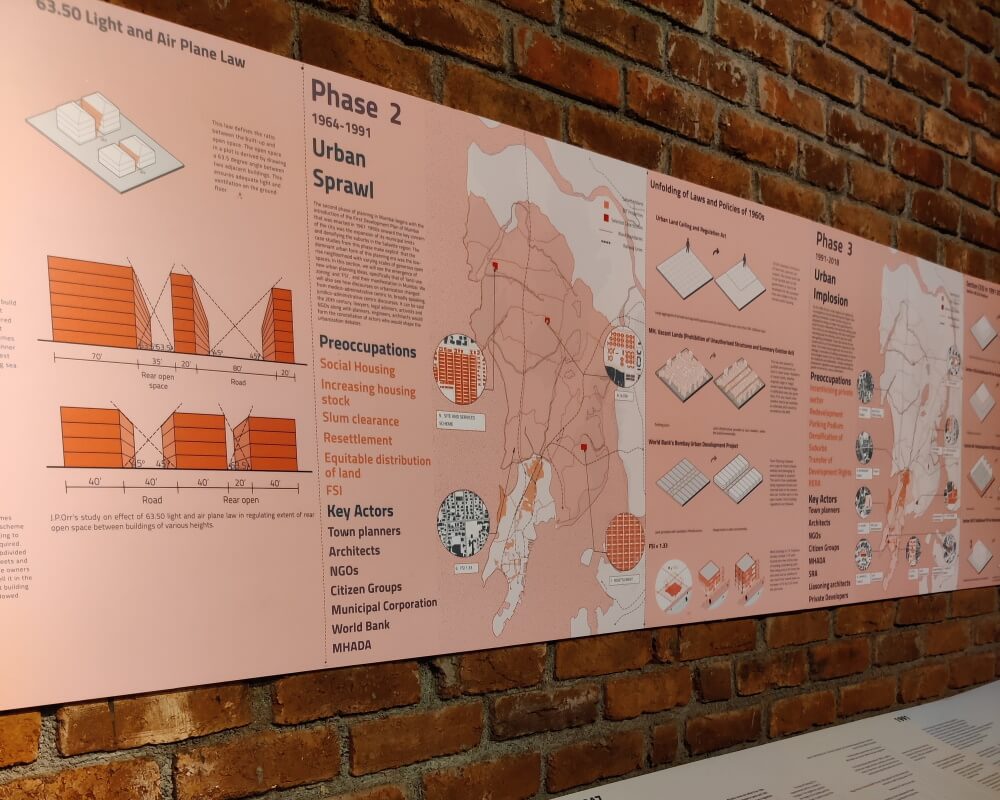

For instance, through models, maps and illustrations of the buildings and homes the team studied, Padora showed how light and ventilation played important roles in the first set of town planning guidelines laid down after Bombay was brought to its knees by the plague in 1896. At each milestone on the timeline, the maps and illustrations showed the changes in building codes or the DCR and their impact on the city’s built form. In doing this, the exhibition offered important insights into the history of Development Plans and regulations in Mumbai, and merged the historical impact of these on town planning and built form.

Padora divided the exhibition into four chronological sections. The first was from 1896 to 1933 when ideas of modern town planning first found root in the then British Bombay. “In September 1896, Mumbai became one of the first cities, after Hong Kong, to be engulfed by the plague. The devastating consequences of the plague on both life and the city changed the urban form and geography of Mumbai forever,” read the plaque. The plague came from the East but the measures to counter it came from the United Kingdom in the West. The plague led to the establishment of the Bombay Improvement Trust (BIT) which formulated the first set of urban strategies and building regulations to counter the epidemic. The first building codes, therefore, focused on light and ventilation, health and sanitation. It also set in motion the process of suburbanisation of the city, a process that continues to this day as people move to the far suburbs stretching 60 kilometres from downtown.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

The changing landscape, use of land

The second phase was the introduction of Mumbai’s first Development Plan (1964), the gradual shift from housing that focused on the health of its residents to the development and expansion of the city’s municipal limits and the densification of the city’s suburbs. This phase marked the emergence of new terms such as Floor Space Index (FSI) and land-use zoning. This phase was about increasing the housing stock, resettling people from one part of the city to another, and a nod to social housing with an emphasis on low-rise neighbourhoods with generous open spaces.

The third phase from the post-liberalisation 1991 to 2018, the exhibition points out, was when the private sector was incentivised in Mumbai’s housing, re-development of slums and old buildings became the buzzword, podium parking lots were introduced, and suburbs were densified “to ease the congestion” created by informal housing in the main city. The Maharashtra government resorted to demolishing slums and evicting slum dwellers on the grounds that they were “encroachers” and contributed to the “filth in the city”. Agitations and movements resulted in recognising housing as a right, but the government rehabilitated them elsewhere. Later, in 1995, the Shiv Sena-BJP government launched the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme with the Slum Redevelopment Authority determining the built form.

The Second Development Plan (1991 to 2011) was when development regulations included re-development in a major way in which land became a tradeable or transactional commodity. These decades showed a shift in the focus of the regulations – from the early health-based model of housing to the revenue-generating model. This led to a number of livelihood and health problems for residents – slum dwellers – of the redeveloped buildings with the ‘Doctors for You’ report highlighting that one in five suffered from respiratory ailments that could be traced back to building design.

The concluding section offered projections from the learnings of these three phases of building codes and DCR, highlighting and flagging off the lurking challenges in the future for architects, planners, and citizens of Mumbai. There has been a 180-degree turn in the city’s housing regulations and the pandemic made it worse. The bottom line in Padora’s analysis is that there needs to be a paradigm shift in the way Mumbai is developed where housing should be more adaptable without the need to reconstruct and must be oriented towards the more vulnerable too.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

Challenges ahead for a congested city

Besides pointing out the impact of building codes and DCR over the decades, the exhibition also articulated concerns about the current regulations for the future of Mumbai. For instance, one area of concern was the increasingly ageing housing stock. This is a challenge that the city of Mumbai has to constantly negotiate. The question is not merely how to repair and reconstruct older buildings but also how to make the reconstruction or redevelopment sustainable and equitable?

Three significant development regulations that were introduced in the city promoted privatisation and imbibed a market-led development objective — the re-development of cotton textile mills, slum redevelopment schemes, and the Transfer Development Rights (TDR) all of which adversely impacted Mumbai’s development and, consequently, its built form. The latest Development Control Regulations (DCR) is formulated using an individual plot-based development approach and promote a Floor Space Index (FSI)-led development model which incentivises builders to build more segregated forms of housing for different socio-economic classes of the city. This applies to new constructions as well as to re-developed SRA projects. How does one look at redevelopment as a part of the urban form and not merely as a business or revenue-generating activity, is a question that “(de)Coding Mumbai” bravely puts on the table.

Padora’s approach to a critical aspect of Mumbai’s built form made it amply clear just how the current DCR led to lowering the standard of living and quality of life for slum and pavement dwellers who had to make do with the densely-packed towers with hardly any breathing space between them – and therefore how cluster development and SRA projects meant further ‘slummifying’ the city. Through painstaking research, with historical references, and well-mounted plaques, maps and illustrations, Padora has asked critical questions about the city to those who draw up its development regulations. They – the politicians and bureaucrats – are unlikely to engage but even if public conversations about de-coding Mumbai gather momentum, Padora’s labour of love would be worth it.

Jashvitha Dhagey developed a deep interest in the way cities function, watching Mumbai at work. She holds a post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic. She loves to watch and chronicle the multiple interactions between people, between people and power, and society and media.

Cover photo: Jashvitha Dhagey