Based on your work, what is the impact of long-term exposure to heat on various people?

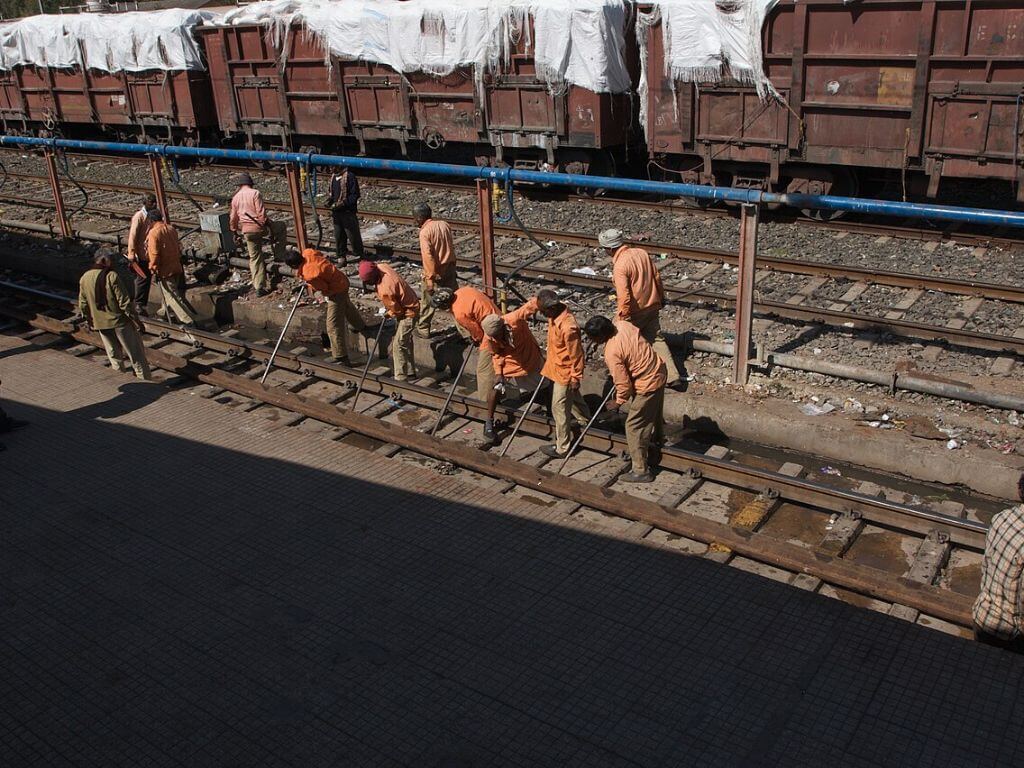

Heat works in a variety of ways. The biggest impact is on outdoor workers — sanitation workers, construction workers, street vendors, ASHA workers and others working under extreme heat for extended hours. The nature of our urban spaces means they don’t have access to rest, shelter, cooling, or amenities such as hygienic washrooms. But it’s also domestic workers in really hot kitchens or workers in textile factories and Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSME) units who are impacted.

The way in which heat works is that significant exposure, lack of hydration, rest or cooling elevates the core body temperature. The impact varies. I will talk about three large heat-related illnesses. One is heat cramps where you are exposed to heat for a long time and you feel uncomfortable, sweat a lot, your muscles ache and your ability to function is compromised. Second is heat exhaustion with symptoms like dizziness, nausea, headaches, extreme thirst and fatigue. In the groups I described, there are instances of kidney stones, gastro-intestinal issues, and among women, urinary tract infections and fungal infections, too.

Third, there is the emergency condition of a heat stroke. In this, the body doesn’t sweat but temperature shoots up and the person faints. It feels like the person has a fever, is delirious and confused. They have to be immediately hospitalised because, without emergency care, it can be fatal. One of the things we talk about in our heat health information sessions with communities is how to provide emergency care for heat stroke such as moving the person to a cooler place, raising their legs, and applying ice or cold water to their body while waiting for emergency help. The first two – heat cramps and exhaustion – are where hydration, breaks, amenities, shade, and cooling are necessary.

What are some of the ways in which people cope with extreme heat?

I love that you use the word ‘cope’ because there’s not much adaptation. It is about coping in the workplace and at home. When we surveyed 166 gig and platform workers in Hyderabad on how they cope with extreme heat, the general response was resignation. Well over 40 percent did not have access to cold and clean drinking water in public spaces; nearly 69 percent lacked access to clean washrooms. What can they do when there are few green spaces and there’s a challenge to access even those?

Avoiding work between 12 noon and 3-4pm is the last resort because it means a decrease in income; they do it only when the situation is severe. In fact, 43 percent of workers said they want a pause in those hours along with compensation. The water they carry turns hot, buying water increases their expenditure, there aren’t many water units to refill. In Hyderabad, people told us that they cannot refill bottles in some of the water stations; they are only allowed a glass of water.

But the challenges extend beyond the workplace. Not only are workers exposed to extremely hot conditions at work, they also return to low-income badly-ventilated settlements which are hot at night too, which means they are unable to cool down and rest effectively. People use all kinds of self-cooling methods during extreme heat. Some wet a bedsheet or dupatta and hang it near doors and windows for cool air. Others cover their heads with a wet handkerchief or cloth, sprinkle water on the floor, sleep on the floor instead of mattresses, or wipe the body with a wet cloth. Many also drink chaach, lemon water, other homemade cooling drinks and rest in shaded public areas like under trees or flyovers.

At HeatWatch, you have been conducting heat-health workshops. What have the responses been like? What do the authorities say?

Being able to recognise the risks of exposure to very hot temperatures has been eye-opening for many. There is also acknowledgement that behavioural changes at the individual level are vital but as we note in every session – this is not an individual problem, it is a systemic challenge. A challenge that employers, governments, and the rich need to do the most to solve. This is a question of climate justice.

A lot of the demands are interlinked with questions of caste, gender, wages and social protection. ASHA workers, for example, have been fighting for fair wages for decades, across the country. Now they also grapple with high temperatures and significant health risks. We worked with them and the Centre for Indian Trade Union in Haryana where they categorically demanded that government programmes and other ad-hoc emergency work should not be scheduled during extreme heat conditions. This highlights that while changing work hours is important, it cannot come with unreasonable targets or added pressure at other times of the day, especially for workers already denied a living wage.

How is their health being safeguarded? Do they have access to Primary Health Centres (PHCs), receive health insurance and regular health checkups? ASHA workers risked their lives during COVID but did not even get adequate wages, forget additional compensation. Our findings across worker groups make it clear: vulnerable workers urgently need social protection to survive the twin threats of extreme heat — devastating health impacts and loss of livelihood. If heat waves are a public health crisis, then governments and employers must ensure greater compensation, stronger social protections, and rights-based support for those most exposed.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Indian cities are seeing incessant construction that’s worsening the Urban Heat Island effect. What actions can city makers take to protect workers?

A number of urgent steps are needed to adapt to extreme heat, starting with expanding, not reducing, green spaces. Why are mangroves in Mumbai, trees in Bengaluru and Kolkata, and forested areas in Hyderabad still being cut down for flyovers and roads? Destroying green spaces worsens urban heat, leaving those outdoors without any respite.

In a fragmented society like ours, access to cooling spaces needs deep and careful thinking. Dr. Rajashree Kotharkar’s study in Nagpur showed that street vendors lack access to cooling centres. These, much like green spaces, must be truly accessible to all regardless of identity, caste, class, or gender. City planners must also recognise that temperatures are not uniform across a city. Low-income settlements experience higher temperatures and are far more vulnerable. There must be clear responsibility and action with expansion in social housing projects. Expanding solar power, returning to traditional architectural practices, and designing public infrastructure from bus shelters to footpaths and markets with built-in shade and cooling are critical. All of this must be done intentionally, by design.

Some cities have Heat Action Plans distinct from Development Plans. How can they be integrated?

Development Plans are crucial, but the question is: how relevant and responsive are they to rapidly changing realities? We are good at producing guidance documents but weak on implementation. Take Delhi’s Heat Action Plan—it recognises the unequal impact of heat but lacks regulatory teeth and financial backing. Meanwhile, the deeper issues—inter-departmental coordination, funding clarity, and enforcement—remain unresolved. There’s still no plan to involve employers, especially in the informal sector, where most vulnerable workers are.

Development Plans often sanction construction over green spaces and water bodies, directly worsening the Urban Heat Island effect. Then, we try to patch the consequences with HAPs. This is treating symptoms, not the root causes. Development must integrate climate resilience from the outset, not as an afterthought. We are already in the middle of a public health crisis driven by extreme heat. Future planning must start with an honest recognition of this.

Photo: HeatWatch

You mentioned that heat is a health disaster not recognised by governments. What support should the state provide?

The government has issued important guidelines to address heat as a health crisis, such as the 2021 National Action Plan on Heat-related Illnesses, the 2024 Emergency Cooling Guidelines on Severe Heat-related Illnesses, and the 2024 Autopsy Guidelines for Heat-related Deaths—all under the National Programme on Climate Change & Human Health and National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC). While these are important, their impact is limited due to poor implementation.

Hospitals often lack the infrastructure to handle severe heat cases; many doctors and healthcare workers are unaware of these guidelines. The state has set up heat stroke units in a few cities like Delhi but these are too few, and Primary Health Centres (PHCs) remain under-equipped. Our sessions with ASHA workers revealed that only one out of 50 in Rohtak had heard of the protocols. There are also serious gaps in training frontline health staff.

Another major issue is the lack of standardisation in identifying heat stroke deaths. As our report shows, deaths from heat are often misclassified, much like during COVID, making families ineligible for compensation.[1] Although new autopsy guidelines have been issued, hospitals lack the capacity to implement them. The state must ensure robust infrastructure, standardised reporting, training for health workers, and clear pathways for compensation. Without these, the guidelines remain only on paper.

Do you see a caste angle too?

All of the above gets more complex when we consider caste and identity. Arpit Shah has a paper on heat exposure among workers; of course, Dalit workers are most exposed to heat.[2] They argue that mitigation plans in India must account for casteist practices characterised by the division of labourers and not just division of labour. This extends to healthcare access. Heat Action Plans and mitigation strategies rarely address this structural reality. To truly tackle heat as a social and public health crisis, solutions must be shaped by those most affected. This means placing Dalit voices at the centre of policy-making, ensuring their knowledge, demands, and experiences directly inform how workplace safety, access to cooling, and healthcare are designed and delivered.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Governments and employers see the impact of heat in terms of productivity loss though it is more than that.

Productivity is the language that employers and multilateral organisations use because it fits into economic calculations but, in a largely informal economy like ours, this metric barely captures the full extent of the harm. Heat leads to serious health issues and deaths which “productivity” cannot account for. Yet, productivity remains the dominant concern for those in power. But productivity for whom?

Worker groups challenge this because it ultimately benefits corporations and governments, not them. Despite meeting harsh productivity targets, many workers don’t earn a living wage and face unsafe, unbearable working conditions where rest and breaks are denied. We must shift the narrative. Heat is not just an economic issue but a systemic one that worsens existing inequalities. The real question is what messaging will force change. Will it be the threat of nationwide strikes? The scale of public health emergencies? The rise in heat-related deaths? We must rethink not just workplaces but the way we design and imagine our cities in a warming world.

What will it take to move the needle towards action?

Individual action is my biggest frustration. It’s a convenient narrative used to shift responsibility away from those most accountable such as governments and corporations driving fossil fuel expansion and environmental destruction. Of course, living sustainably and resisting consumerism matters but it’s not enough. What we need is structural change. We must ask what we are choosing to pay attention to. At HeatWatch, we focus on cities but the real violence is unfolding in places like Hasdeo, Bastar in Chhattisgarh, in the Nicobar islands, and in Odisha, where coal and minerals are mined to power our homes and devices, and Adivasi lives are sacrificed in the name of development. Rising temperatures there, and their displacement, erasure, do not feature in mainstream responses.

As long as we live in a society that exploits land, labour, and life especially of Adivasis, Dalits, and marginalised communities, our solutions will remain piecemeal. Heat Action Plans are band-aids. What we need is deep, deliberate mitigation. We already know how deforestation, mining, and unchecked construction worsen heat locally. So, yes, adaptation is necessary but it is not enough. To truly confront the heat crisis, we need bold public investment, sweeping social protections, and a radical rethinking of how we live and work. We are nowhere close to that yet.

Jashvitha Dhagey is a multimedia journalist and researcher. A recipient of the Laadli Media Award consecutively in 2023 and 2024, she observes and chronicles the multiple interactions between people, between people and power, and society and media. She developed a deep interest in the way cities function, watching Mumbai at work. She holds a post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic.

Cover Photo: Wikimedia Commons