The generous cool shade of trees providing relief from brutal summer heat is an elementary idea found in children’s books and, traditionally, in villages. What if the trees, their flowers and fruits, and shade could be collectively planned and grown and, then, enjoyed by people in urban neighbourhoods? They would have, in essence, made community gardens – an idea that acquires urgency as India’s cities become hotter every summer and poorer people find themselves shut out of parks and gardens.

Community gardens, academics say, are “open spaces managed and operated by members of the local community in which food or flowers are cultivated,”[1] decentralised green spaces designed to serve the needs of the community. They have quietly happened at Jakkur Lake in Bengaluru and in Perumbakkam Resettlement Site in Chennai. Unfortunately, the Chennai initiative is nearly over.

If done right, community gardens not only provide cooling but yield shade and fruits for people conventionally disallowed into public or private gardens. They foster a sense of participation and ownership in the community. “Unlike public parks and other green spaces maintained by local governments, community gardens are managed and controlled by a group of unpaid individuals or volunteers…The purpose is to provide an open space for learning about sustainable growing practices, building relationships, and developing a sense of belonging,” states this explainer.[2]

“In a typical Global South city, who you are and what you do determines your exposure to heat and proximity to a green space,” Dr Manan Bhan, researcher at ATREE noted at the Cities in Action webinar hosted by the Indian Institute of Human Settlements. “Many functional parks in many of our cities are closed off to the people who need them the most… It’s not enough to have green spaces concentrated in a specific part of the city,” he said, referring to the iconic and large Cubbon Park and Lal Bagh in Bengaluru.

Photo: Ananas Studio

Rethink of green spaces

Community gardens offer greater access to cooling to more people and, therefore, address thermal or heat injustice too. Green areas help to lower the temperature in their surroundings. A study in Delhi[3] in 2024 found that large parks with dense greenery and water bodies cool surrounding areas up to 8.28°C. But anecdotal experience shows that aesthetics dominates their layouts, access remains a major class issue, and their produce – if any – cannot be claimed by people.

Aesthetics have dominated gardens and parks – making them attractive, using appealing plants even if non-native, limiting activities to specific spaces such as walking or jogging tracks, maintaining manicured lawns out of bounds for people. This ornamental template restores some green and the coolness, but leaves out people. When parks and gardens are closed, by mandates, during the hottest part of the day, outdoor workers are locked out. If locals cannot claim the flowers and fruits, it’s a fracture between the place and people.

Recent research on Bangalore’s public parks reveals sharp inequities. A study[4] found that around 19 of the city’s 198 wards had no parks while 36 wards had only one, half of the wards had parks beyond walkable distances, and, importantly, neighborhoods with higher Scheduled Caste populations were most deprived of green space access. A study by ATREE[5] in Bengaluru found that the absence of shade, vegetation, and green spaces amplified the Urban Heat Island effect, making densely built – poorer – areas 3–5 degrees Celsius hotter. Clearly, it’s not enough to have parks and gardens in denser areas; everyone in the community must have access to them.

Community gardens are more participatory, rooted in the idea of care than physical green space only. They often regenerate a neglected, wasted, or underused plot, and open their produce to the community. As a former manager at Jakkur Lake told me, “This community garden is for everyone – for fishermen who live here, walkers, volunteers, everyone. They can take the produce, take cuttings and propagate the plants at home too.”

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Jakkur Community Garden

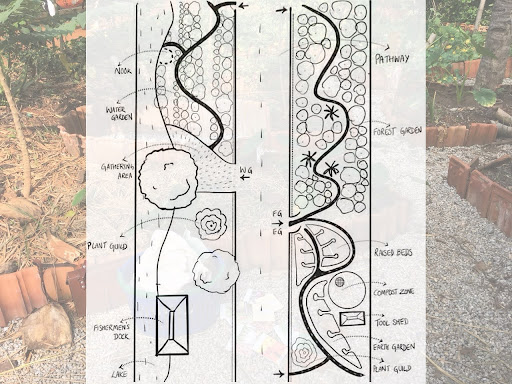

North Bengaluru’s Jakkur Lake, once a neglected waterbody, is a site of community-led ecological restoration. It has been revived through the efforts of residents, the citizens’ collective Jala Poshan, and design firm Ananas Studio. On its banks is a thoughtfully-designed community garden, built with local materials and shaped by the people who live and work around the lake.

The garden was intentionally designed for inclusivity, said Annapurna, a founder of Jala Poshan. “The idea was to see if urban commons could be used to grow food for the marginalised,” she explained. Jakkur lies in a peri-urban part of the city, its users are migrants and locals alike. This also informed the planting strategy: Hardy, low-maintenance, and nourishing crops like tree spinach and other perennial greens which thrive round-the-year and meet a range of dietary and cultural needs.

The garden is accessible to everyone irrespective of how long they have lived in the area. Unlike traditional parks, the cost of establishing this was kept low through community involvement. “The land was part of the urban commons, available for citizens to use. We got a grant of about Rs three lakh from the Bangalore Sustainability Forum,” Annapurna explained. Once the idea took off, it was sustained with “community donations like someone bringing saplings from home or using kitchen waste to sprout greens,” she added.

The citizens’ collective Jala Poshan worked out a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU)[6] with the municipal corporation, allowing the development of the lake’s periphery. After the initial construction by hired labour, 15 to 30 participants volunteered every week. The community also helped in constructing infrastructure and setting up irrigation systems. The project started in late 2017 and was formally wrapped up in 2020[7] Theertha, lake manager involved in managing the site and maintaining the garden, said, “Every Saturday, there was Shramadan. People from the community or a company or school students worked together on a part of the garden. It was interactive—a lot of information was shared about what was planted, what methods were used, and we talked about working with the soil.”

The maintenance costs ranged between “Rs 30,000 and 50,000 annually depending on what we are trying to grow and how involved the community is,” Annapurna added. Funds are raised through small community donations or corporate contributions. The zone around Jakkur Lake is home to many shady trees, a veritable urban forest – a shaded and pleasant area available to everyone around.

Photo: Chennai Resilience Centre

Perumbakkam Resettlement Site

Chennai’s Perumbakkam Resettlement Site is home to communities displaced from their slums near Adyar and Cooum rivers in the 2015 floods. Cut off from the city, residents navigated long commutes, lost livelihoods, faced social stigma and, even, flooding.[8] In 2022, the Chennai Resilience Centre (CRC), in collaboration with Okapi Research, the Information and Resource Centre for Deprived Urban Communities (IRCDUC), and Sembulam set up the community garden – not only as an ecological intervention but also a livelihood strategy.

The garden, across 1,000 square feet, required permission from the Tamil Nadu Urban Habitat Development Board and Rs 20,000–25,000 as fee. It was a part of the Chennai Urban Farming Initiative, primarily funded by Adrienne Arsht-Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center (AARFRC)[9]. The Chennai Resilience Centre was the key implementing agency with Okapi as the monitoring-evaluation advisor. “We were trying to show that urban farming is not just for middle-class rooftops,” said Dr Parama Roy, executive director at Okapi, “In vulnerable communities, the need is not green space for recreation only but food and income.”

Vanessa Peter, policy researcher and founder of IRCDUC, said securing the land was difficult: “Even raising the nominal lease amount became a big challenge.” The Chennai Resilience Centre provided seeds, soil, and training support while IRCDUC funded the fencing, water access, and day-to-day operations. Women from the community, through their self-help groups, maintained the garden using organic pest control methods like chilli water. “They were keeping the books,” Peter said. In late 2023, they had harvested over 15 kilograms of produce and sold some locally.

A single garden cannot meet the needs of hundreds of people in the resettlement site, and limited yield sometimes led to tensions. Also, “there’s a hierarchy of needs here,” Dr Roy explained, “People are more concerned about immediate needs of food, income, just meeting daily needs. Therefore, everyone in the community may not perceive the garden as something of immediate benefit”. Still, women like Sandhya from the community had kept the garden running. “We harvested several vegetables like tomato, brinjal and spinach,” she said. When they were moved to Perumbakkam, the garden helped support their livelihoods and gave them chemical free produce; its shutdown was heartbreaking.

Though it functioned for over two years, repeated floods in 2023 and 2024, funding gaps, and an expiring lease forced it shut. Safety concerns, stray cows, and the risk of theft complicated open access. A larger plot would have enabled one or two crops with sufficient yields, enabling the women to sell the produce or process it into products like pickles. Dr Roy said that a community garden has potential if “a substantial number from the community get involved in it from a livelihood angle.” Its shutdown reveals systemic obstacles. The garden cannot be rebuilt without addressing the flooding issue.

Photo: Ananas Studio

Calls for a reimagination

The two experiments show that community gardens need not to be in middle-class complexes or hobbyist spaces only. They can be in resettlement colonies, built around livelihoods and access to food – something overlooked in urban planning. If such spaces are to take root in cities, we need to reimagine community gardens, who builds them, and what purpose they serve.

The history of community gardens, also called workers’ gardens or allotment gardens in other countries, offers an insight. “Community gardens developed in cities during periods of crisis whether economic, social, environmental or war-induced (as evidenced by the existence of “war gardens” or “victory gardens” during the two world wars)…It seems that the current return of agriculture[10] in cities would be part of this dynamic. Through the diversity of their socio-spatial organisation, (they) offer fertile ground for innovation and open up perspectives for the management of open green spaces in the city,” concluded this research.[11]

In dense cities across India, even public infrastructure like schools and Anganwadis (Integrated Child Development Services centers) can be the space. “These already exist in neighbourhoods, many of them have flat rooftops or adjoining open space that goes underused,” says Dr Roy. These gardens can offer shade, nutritious food, thermal relief, and even a learning opportunity for the children. The benefits are many – from well-being to environment. They play a crucial role in climate action. “These spaces serve both an adaptation and a mitigation benefit,” says Dr Bhan, “They can sequester carbon and also help people adapt to the environmental changes especially when it comes to heat stress.” In cities prone to flooding like Chennai and Mumbai, they offer “additional adaptation benefits.”

The Chennai Resilience Centre (CRC) implemented a community rooftop garden at Anbagam shelter for women. A study showed that from 6am to 6pm, the room below the garden stayed 2-3 degrees Celsius cooler than the room below the exposed terrace, and on the hottest days of the year, the room below the garden was up to 7.5 degrees Celsius cooler than others. “Why is it that most greening processes happen in elite areas, why not in resettlement sites,” Peter asked, calling for a city-wide shift, linking them to schemes like the Tamil Nadu Urban Employment Scheme to generate jobs to build and maintain the gardens.

Community gardens are spaces not only accessible to people in a neighbourhood but also tailored to the local context and needs, shaped by people themselves. Ultimately, as Dr Bhan says, parks and community gardens are socio-ecological spaces that balance human needs with environmental health, offering a model for future green urban spaces that can be incorporated into plans for cities. There’s no reason that there cannot be more of them.

Poorvi Ammanagi is an Urban Fellow at the Indian Institute for Human Settlements, currently interning with Question of Cities. Based in Belagavi, Karnataka, she is interested in exploring the intersections of ecology, small-town transformation, and young people’s place in urban landscape. With a degree in Mass Communication from the Symbiosis Centre for Media and Communication, she uses film, print media, and research to document small towns.

Cover photo: Ananas Studio