It’s more than half a century since the French sociologist and philosopher Henry Lefebvre coined the term ‘Right to the City’ in his book Le Driot a la Ville in 1968. Challenging the capitalist construction of a city which essentially serves the wealthy few, Lefebvre’s slogan was political in nature. It is commonly understood to have two dimensions: the right to belong to a city and co-produce urban space, and the right to work, education, health and leisure in an urban context.

The Right to the City isn’t an extension of our basic rights; it is a basic right in itself, one that becomes increasingly important in the context of rising urban inequality and growing spectre of Climate Change. While Brazil, Canada, and France have incorporated the Right to the City in their legal framework, the conversations around it in India have been scattered though well-meaning. India’s urban population has been increasing over the decades and cities have expanded. About 35 per cent of the country’s population lives in its cities, according to conventional data, but if the cyclical migration into and out of cities is taken into account, the numbers may well be beyond three out of every ten. There has also been an increase in amenities and resources. But are they equally available to all those who live in cities? Are they affordable? Why are some urban inhabitants seen as more deserving of these than others?

The Right to the City acknowledges that every inhabitant of a city contributes to the life of a city and hence, has the right to be involved in its betterment. The right has been recently interpreted by courts even if only in terms of social and physical amenities available to people. But how do these services and amenities stack up, how much is there in each city?

Question of Cities takes a look at the fundamental resources required for survival to ascertain the kind of access that the cities provide to their inhabitants.

Ecology

Ecology

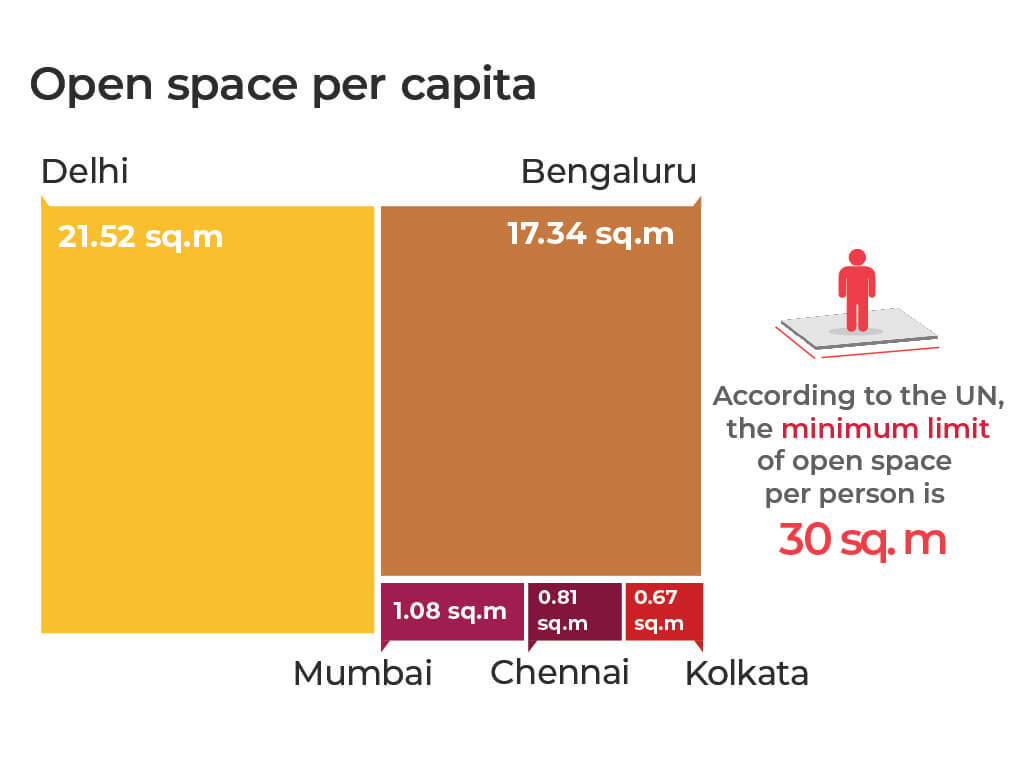

Open space is any open piece of land that has no buildings or other built structures and is accessible to the public usually for recreational purposes. According to the guidelines set by Urban and Regional Development Plan Formulation and Implementation (URDPFI), the minimum area of open space required for a person is 10-12 square metres. Delhi and Bengaluru are the only cities that cross this threshold.

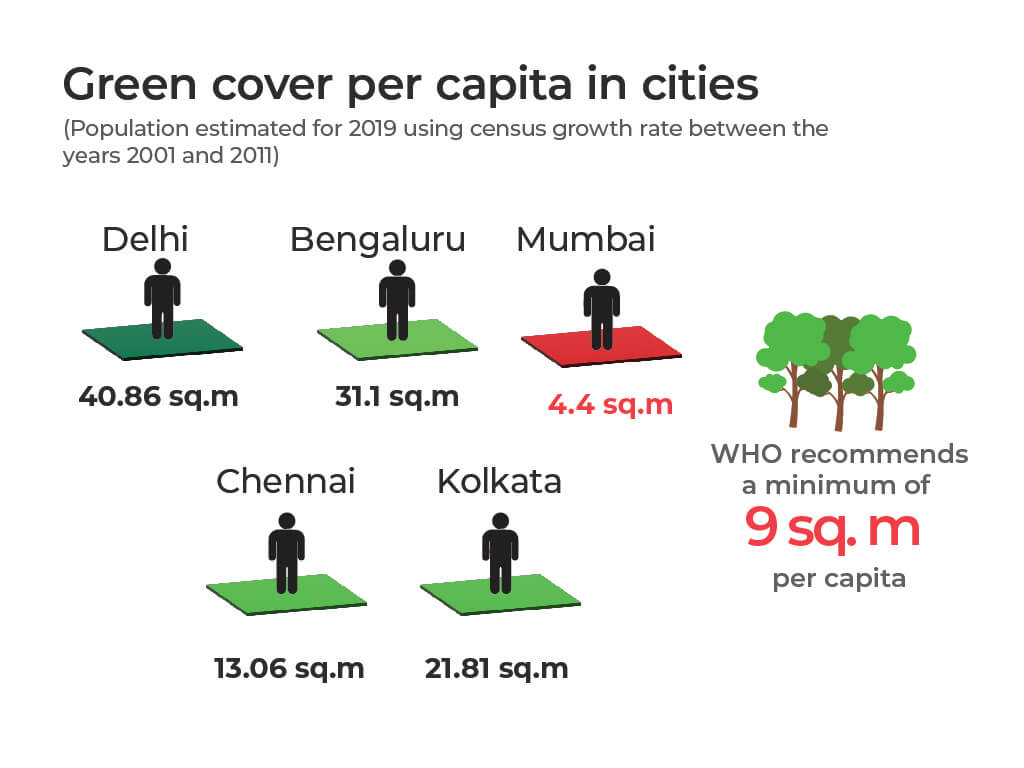

Often, the terms ‘open space’ and ‘green space’ are used synonymously. But open spaces are not green spaces or green cover. Green cover is land that is partly or completely covered with grass, trees, shrubs, or other vegetation and stands as the lungs of a city. Green cover includes parks, community gardens, and so on.

Incessant construction under the guise of development has stripped our cities of their natural areas. Water bodies have turned into stagnant drains and open areas turned into dump yards. The changing topography of cities has rendered them almost unrecognisable, for the worse. Mumbai fared the worst in terms of its green cover with only 12.31 per cent greenery. Delhi with 56.2 per cent has almost five times more green cover than Mumbai.

However, this is not equitable among all citizens. Having the lowest green areas within its municipal limits, Mumbai also has the least amount of green cover per capita. The citizens of Delhi enjoy 10 times more green cover than their counterparts in Mumbai.

Housing

Housing

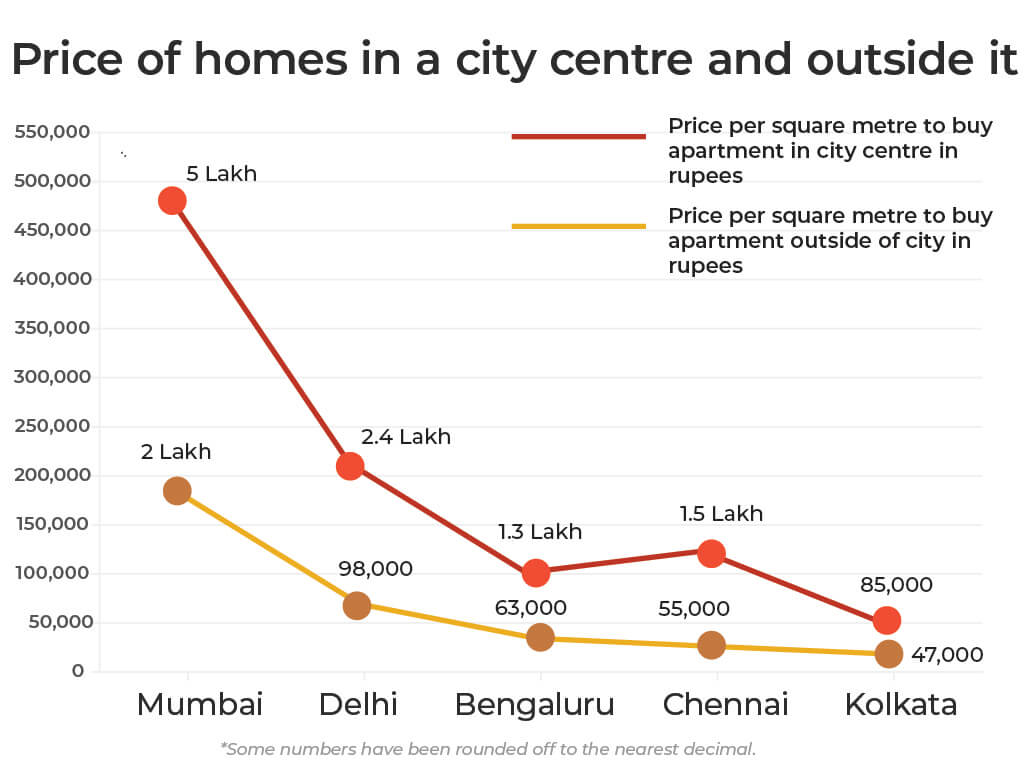

While cities continue to expand to suburbs and far suburbs, their centres still remain prime areas for residential accommodation. Buying a house in downtown, or the centre of a city, costs almost twice the price on its outskirts in all major cities except Chennai, where it is three times. The sheer cost puts houses out of the reach of a large majority of people who live in cities – or forces them into less-equipped and congested accommodation such as slums or informal settlements.

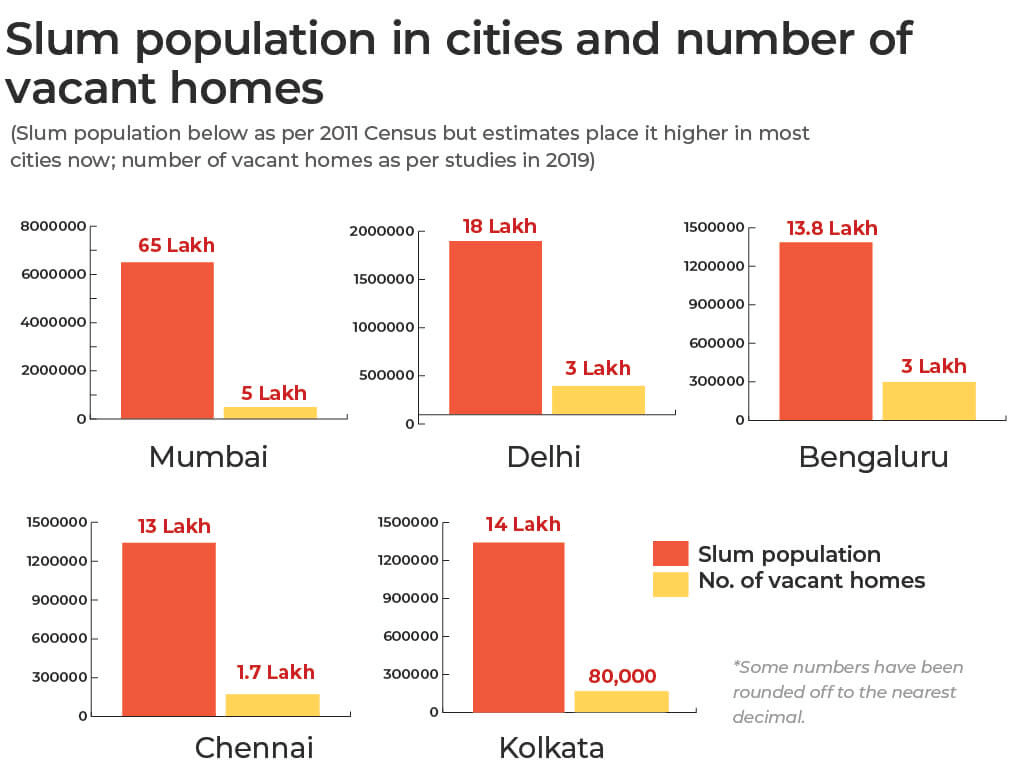

Affordable and inclusive housing is a distant dream for a large majority of people in all cities. This forces many to make their homes in slums or informal settlements, even make-shift homes on pavements. The availability of houses is linked to the housing market and profits derived from it, rather than the demand for affordable homes. This, in turn, leads to the construction of unaffordable or luxury houses, many of which then lie vacant. India’s cities have lakhs of unsold or unoccupied houses while many more lakhs live in congested slums with sub-par amenities.

Water

Water

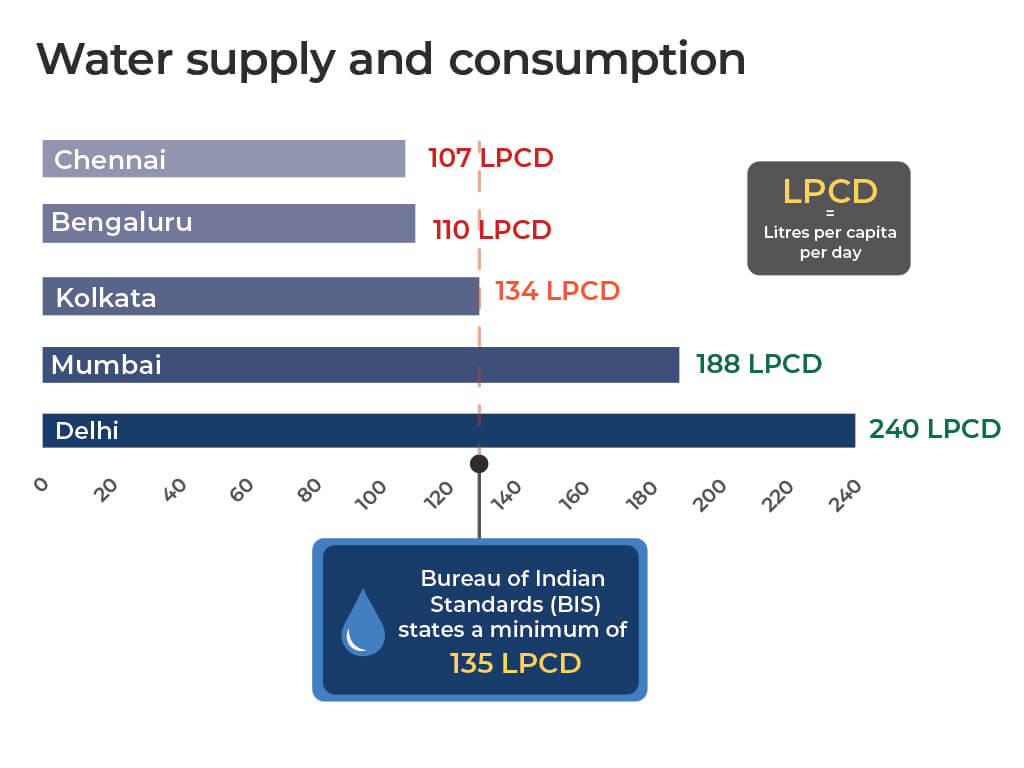

According to the norms set by Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS), cities need to supply 135 litres of water per person per day or 135 litres per capita per day (LPCD). While Mumbai and Delhi comfortably surpass this number, Kolkata comes close only to miss it by one unit. Chennai, which has become prone to floods, has the lowest supply of water at 107 LPCD. It’s important to remember that this is a city-wide average and does not mean that every person in a city has access to the same quantity at the same price.

Health

Health

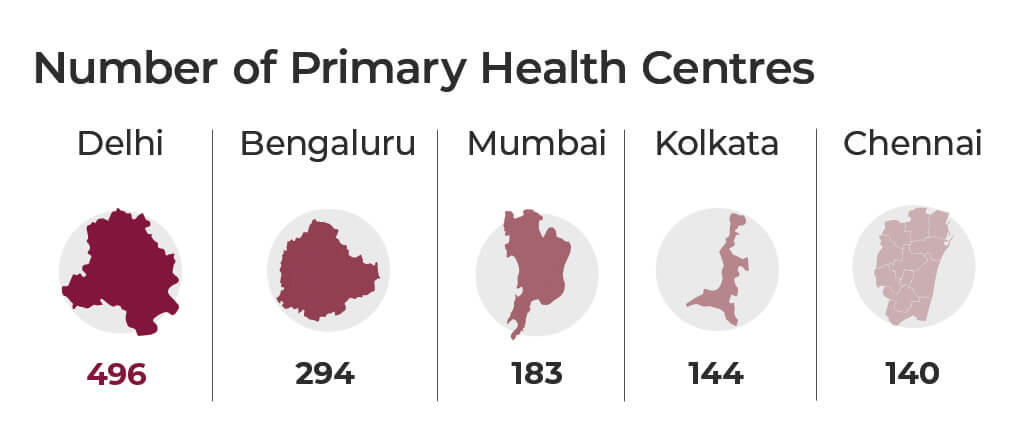

Affordable healthcare in cities begins at Primary Health Centres (PHCs) which are – or should be – the first accessible place for people to reach when they need medical attention. PHCs form an important part of the health infrastructure of a city but often are the most neglected in the healthcare pyramid which sees expensive specialty hospitals at the very top. When public and primary healthcare amenities, like the PHCs, are neglected, healthcare as a right becomes compromised for the large majority. Delhi had the highest number of Mohalla Clinics at 496 while Bengaluru trailed right behind with less than half that number with 224 Urban PHCs in the city.

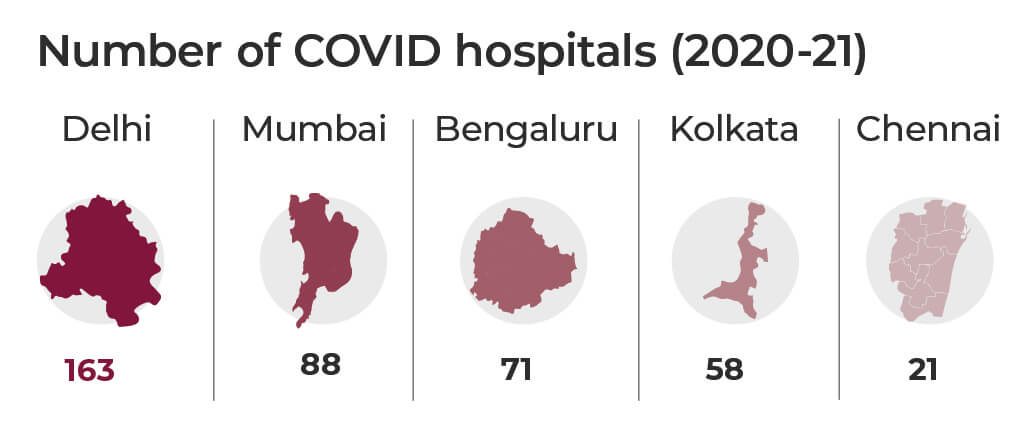

When the COVID pandemic struck, it was the public health infrastructure that proved to be important in offering quarantine facilities. With 163 COVID hospitals, Delhi had the highest number of COVID hospitals among the major cities of India. Mumbai trailed behind with 88 COVID hospitals, out of which 31 were in the city and 57 in the suburbs.

Education

Education

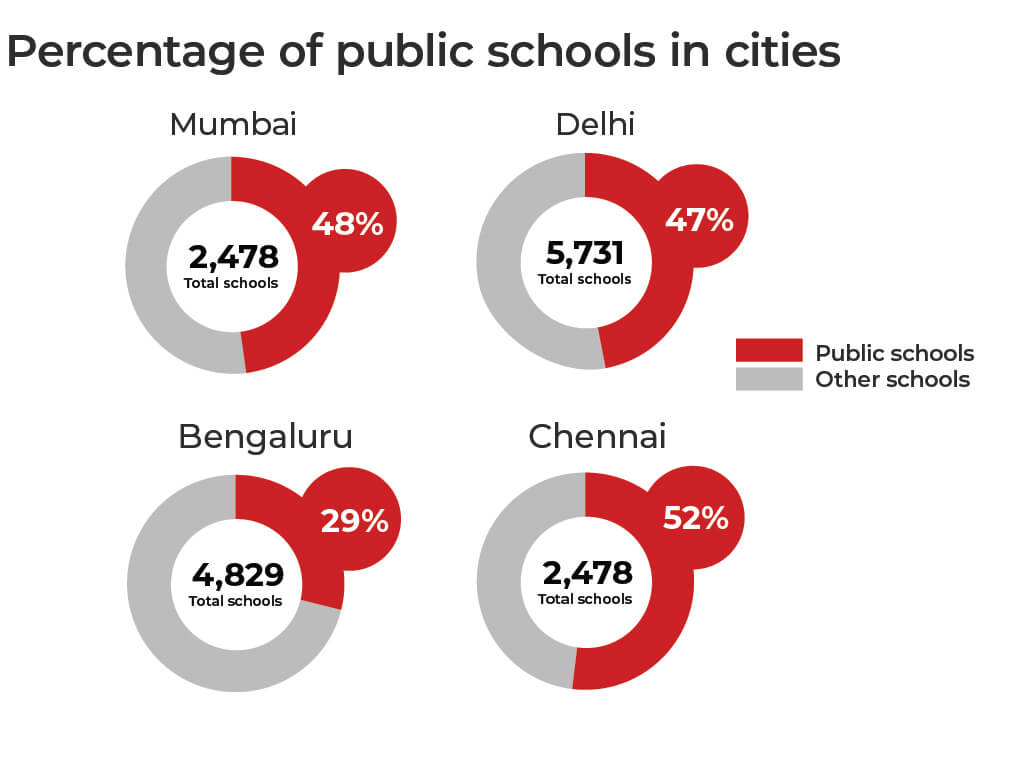

The Right to Education is a fundamental right and it is best implemented across public schools in a city. However, despite its importance in children’s lives, quality education is either unavailable in public schools in our cities or cannot be accessed by children who live far away. Less than half of the 5,000 plus schools in Delhi are public schools. Chennai has only half of its 1,500 schools as public schools. A mere 29 per cent of Bengaluru’s schools, of a total 5,000, are public schools.

India’s cities are commercial hubs and often called engines of the economy. The opportunities in cities draw a large number of migrants from near and far, but those who choose to live in cities for work are usually forced to compromise on the quality of their lives. This, in large part, is because cities are not planned to offer physical and social amenities to all, or equitably to all. Even the average availability of amenities in India’s cities differs but within a city the differences are greater: the marginalised have the least.

Sources:

Jashvitha Dhagey developed a deep interest in the way cities function, watching Mumbai at work. She holds a post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic. She loves to watch and chronicle the multiple interactions between people, between people and power, and society and media.

Rhea Antony is a visual designer and communication strategist who focuses on visualising and telling stories using data on themes surrounding sustainability and urban development. She also works with young organisations to help strengthen their brand through comprehensive communication strategies that help them scale their impact.