When we talk about trees in cities, we quantify their importance by their functions as ecological stabilisers and economic contributors – they aid in absorbing stormwater, reducing carbon dioxide levels, enriching soil, providing shade, supporting a plethora of biodiversity and more. But we do not yet have the complete language to explain our appreciation of, our relationship with, trees. Having tulsi at home, attempting to grow pudina for chai, picking fresh aam from neighbouring mango trees, discovering hibiscus bushes around the corner, smelling raatrani when its flowering season – we all have at least one memory attached to flora and fauna around us.

As news of tree-felling makes headlines, people’s participation in discussions, protests and policy making also increases; the effort is to urge our administrations – tree fellers – to reconsider trees as dispensable. According to the Mumbai Climate Action Plan (MCAP)[1] released by the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation, the city lost 2,028 hectares of urban tree cover between 2016 and 2021. The Indian State Forest Report released in 2021 states that many Indian cities have lost significant forest cover between 2011 and 2021, with Ahmedabad losing 48 percent, Kolkata losing 30 percent, and Bangalore losing 5 percent.[2] While the report also mentions cities that have seen an increase in forest cover over that decade, people’s relationship with trees in cities remains less explored. Here’s a visual essay which goes beyond the data and numbers.

Trees as places of rest

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Established in 1870 under the then British Chief Engineer of Mysore State, Cubbon Park in Bangalore covers an area of almost 300 acres today. It has a vast inventory of exotic and indigenous botanical species with around 6,000 trees which not only aid its immediate micro-environment, but also serve as a place to pause for Bangalore’s many visitors and residents. Cubbon Park’s lush green landscape is well connected with motorable roads and walking paths, often frequented by walkers and plant-enthusiasts alike, with benches placed under expansive green tree canopies.

Time spent whiling away in an urban forest resonates with English novelist John Fowles’ quote, “In some mysterious way, woods have never seemed to me to be static things. In physical terms, I move through them; yet in metaphysical ones, they seem to move through me”.

Photo: Sejal Patel

On 11th October 2023, Dinesh Jaiswal, a resident of Saidulajab, Saket, turned 48. Sushila and Dinesh were out for a walk and chanced upon benches under a tree that usually serve as a bus stop. As they rested on the bench, Dinesh recalls the time when he used to work as an insurance agent, “There were no benches here then, the only resting source was this tree”. He also recalls waiting here for a bus to Mehrauli, and in the soaring heat of Delhi, he would find this tree to be a comforting factor while he waited.

Speaking on trees in similar fashion, British writer and historian Gillian Tindall wrote in The Fields Beneath, “For years, walking round London, I had been aware of the actual land, lying concealed but not entirely changed or destroyed, beneath the surface of the nineteenth- and twentieth-century city. It has been said that ‘God made the country and man made the town’, but that is not true: the town is simply disguised countryside”.

Trees as places of commerce

Photo: Past India

Spread across 2.5 acres of land, the banyan trees in Horniman Circle, South Mumbai, have seen some of the first traders of Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) under its canopies, before it was formalised as a garden. Five stock brokers gathered under a banyan tree opposite Mumbai Town Hall in the 1850s and started trading. As their numbers increased, they moved to different banyan trees located across Mumbai before finally establishing The Native Share & Stock Brokers Association in 1874. Construction of the garden itself was completed around 1872, with well-laid out walkways, trees and a central ornamental fountain. Today, Horniman Circle serves as a much-needed green space in South Mumbai, and lends itself to Sufi festivals and Kala Ghoda Arts Festival annually.

Writer and broadcaster Richard Mabey once said, “To be without trees would, in the most literal way, to be without our roots”, which holds true for the inception of today’s highly valued Bombay Stock Exchange.

Photo: Sejal Patel

Ankit Negi, a vendor in Saidulajab, Saket, says this one tree saves money for many similar vendors here. Ankit sells tempered glass covers as well as masks to people traversing this road. He uses the branches of the Banyan tree to hang the masks with a thin ribbon. “If not for these branches, I would have to invest in the plastic holders, which are not permanent, they break too soon. These branches are strong and survive heavy winds as well as heat,” says Ankit, one of the many vendors who run their daily business under the large canopy of this tree. He says that although his business is temporary as it depends on the mercy of the municipal corporation, the claimed spot beneath the tree helps him feel a bit secure. “If not this, I will find another tree someday,” he says.

“There is little in the architecture of a city that is more beautifully designed than a tree”, according to Jaime Lerner, an architect, urban planner and Brazilian politician.

Photo: Sejal Patel

Apart from Ankit’s small setup, this banyan tree’s multifunctional canopy is home to many activities driven by the pedestrian traffic it sees on a daily basis — one side of the canopy serves as a bus stop. Vendors directly under its shade don’t need roof coverings while the ones on its outskirts resort to using umbrella shades – either way, a variety of street food, small items, fruit and vegetable vendors use this area for their livelihood. A large number of street food vendors often park their carts, stools, tables and other items under trees to use tree cover as a sunshade, as it also provides a shaded area for their customers.

Frank Lloyd Wright, renowned American architect, once said, “The best friend on earth of man is the tree. When we use the tree respectfully and economically, we have one of the greatest resources on the earth”.

Photo: Shobha Surin

Similarly, in Bhubaneswar, a coffee shop has made a home for its park visitors driving home the fact that not only small shops and hawkers, but even big businesses know that a place under trees attracts more customers. A hot cuppa under its cool shade is a soothing recipe for a leisure break. Walter Gropius, German-American architect and founder of the Bauhaus School, speaks on trees in urban settings with poetic sentiment: “Under trees, the urban dweller might restore his troubled soul and find the blessing of a creative pause”.

Trees as places of worship

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

The idea of trees being ‘sacred’ is a common thread among a lot of cultures globally, with trees often being viewed as symbols of life. The Bodhi, the Cedar of Lebanon, the Ashvattha, the Yggdrasil – religions all over the world have a deep rooted connection to certain trees, which is usually passed down through lore, scriptures and drawings. Popularly in India, the banyan tree’s trunk is almost always decorated with white and red thread, with small idols or photo frames of gods and goddesses at its base. Patrons regularly visit these trees in the morning for their prayers, or lightly touch its bark for blessings while passing through. Within cities as well, these trees seem to be anchors of important traditional rituals.

As the author of a paper titled “Now that the trees have spoken”[3] outlining an exhibition in Mumbai presenting the work of four artists, Ranjjit Hoskote writes on their close symbolic relationship with nature: “…They (the artists) are adept at calibrating the gradations of strangeness: in their epiphanies, trees sing in many voices, their trunks morphing into rivers in flood, swollen with uncontainable memories; snails fly, boards fight tigers over territory; ancestral figures across vast distances on tireless horses, and turtles carry the legends of dead islands across the oceans”.

Photo: Shivani Dave

In ancient Hindu religious texts, the Puranas, trees are said to experience happiness and sorrow, have a conscience, and are living beings – trees are a part of samsara, also known as the cycle of life, just like humans. As a result, trees were – and are – revered by many. This reverence often comes with religious tones, as people tend to show their respect through ritualistic means, idol worship or offering flowers.

“For him it meant that everything which existed was interconnected: the trees, the sky, the weather, people, poetry, science, nature. He hunted down facts in the way a magpie collects shiny things. Yet when he strung them all together, somehow they did become stories – of a kind.” – Amitav Ghosh, Indian writer, in The Hungry Tide.

Trees as places of workouts and de-stressing

Photo: Shobha Surin

At the crack of dawn, when trees glisten with dew and the birds are singing their hellos, Bhubaneswar’s walking and jogging crowd makes its way to Ekamra Kanan Botanical Gardens. A lush green landscape in the heart of Bhubaneswar, the 500- acre garden is a treasure of medicinal and heritage trees. With a short trail cutting through the Chandaka forest, the walkers and joggers can enjoy the cool morning breeze, the cacophony of birds — this healthy ritual keeps them connected to nature that might be otherwise absent in a city.

As a pioneer architect of many planned Indian cities, Le Corbusier’s design philosophy for cities rested on what he believed were the most important: “The materials of city planning are: sky, space, trees, steel and cement; in that order and that hierarchy”.

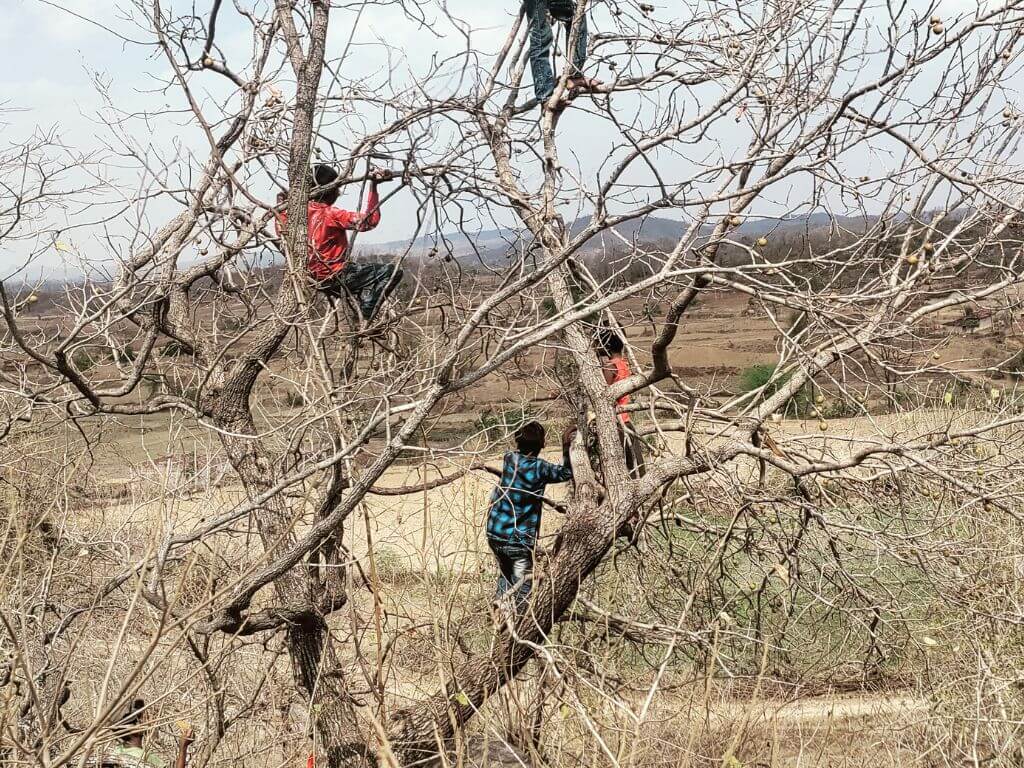

Trees as places of play

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

A lot of our first memories around trees are tied with our childhood, and with a sense of wonder we felt looking at large trunks with giant canopies towering over us. The urge to climb its branches, to find fallen flowers, to step on crunchy dry leaves – we usually grow up playing with and around trees until adults around us forbid us to do so, for safety and other reasons. Manicured lawns and barb-fenced trees become our next step towards connecting with nature, oblivious to our weakening connection with trees around us. Within parks in cities, most patches of grass and trees are forbidden land, only serving an aesthetic purpose, which raises the question – where can a child full of curiosity and wonder climb a tree to experience nature first-hand?

As Patrick Geddes, renowned Scottish biologist, sociologist and town planner, famously said, “But a city is more than a place in space, it is a drama in time”.

Photo: Shivani Dave

As deforestation makes a home in our daily news columns, it is important to acknowledge that this loss of tree cover also comes with a loss of human connection with nature itself. A powerful quote from Alanis Obosawin, an American-Canadian indigenous filmmaker and singer, succinctly portrays what continued haphazard human-intervention will lead to: “When the last tree is cut, the last fish is caught, and the last river is polluted; when to breathe the air is sickening, you will realise, too late, that wealth is not in bank accounts and that you can’t eat money”.

Shivani Dave is an architect, writer and illustrator interested in exploring the intersection of architecture and social sciences. After graduating in architecture from Mumbai, and in media from the London School of Journalism, she is applying the fundamentals of architectural research and writing within urban contexts to develop phenomenological ideas about life in cities. She researches, writes and illustrates in Question of Cities.

Cover photo: Shivani Dave