When I was a young journalist in Bengaluru nearly 20 years ago, I researched water scarcity and groundwater in the city. One of the reports I studied had beautiful maps with rivers, streams, nallahs, valleys and lakes. Along with a photographer, I spent 45 days and around Rs 8,000 on fuel – while on a Rs 5,000 monthly salary – to map surface water and water sources. Back then, I had found the discrepancy between the maps and reality – nearly 50 percent of lakes and wetlands shown on the maps were missing or were being usurped for construction. Land and property were being sold at exorbitant prices to new residents who were unaware of the pitfalls. The water crisis in Bengaluru is hardly new but it has become worse over the years with the city’s growth story.

The old Bangalore had great forever-sweater weather, lands around it were well nourished by precipitation and flowing water which supplied residents with fresh vegetables, fruits, and so on. Throughout my childhood, almost all of today’s suburbs were vegetable farms, rice fields, banana plantations which required water. The old city is perched on a plateau; as it grew outwards, it began to follow the flow of water from the plateau and around the city. The city started on a growth trajectory in the late 1950s and early 1960s when public sector enterprises came to be situated here. Then, the IT-led boom happened.

The only water supply was from reservoirs outside the city because Bangalore itself had few water sources. In the late 1960s itself, there were indications of insufficient water supply and water shortages had begun. From the 1970s, governments tried to get water from the Cauvery – 90 kms away and 1000 ft lower. It is perhaps the most energy inefficient water supply because every drop is pumped, from underground or the Cauvery, using many megawatts of electricity.

In all these decades, there was no plan to harvest water, develop water sources or protect the existing ones. The authorities went for engineering solutions – ‘let us engineer our way out of this problem’ – especially from the Cauvery since 1995 on the assumption that it is an infinite water source. The demand for water has always been four to five years ahead of the supply; the authorities have only played catch-up. This, in a nutshell, is the crisis.

Water problem baked into the boom

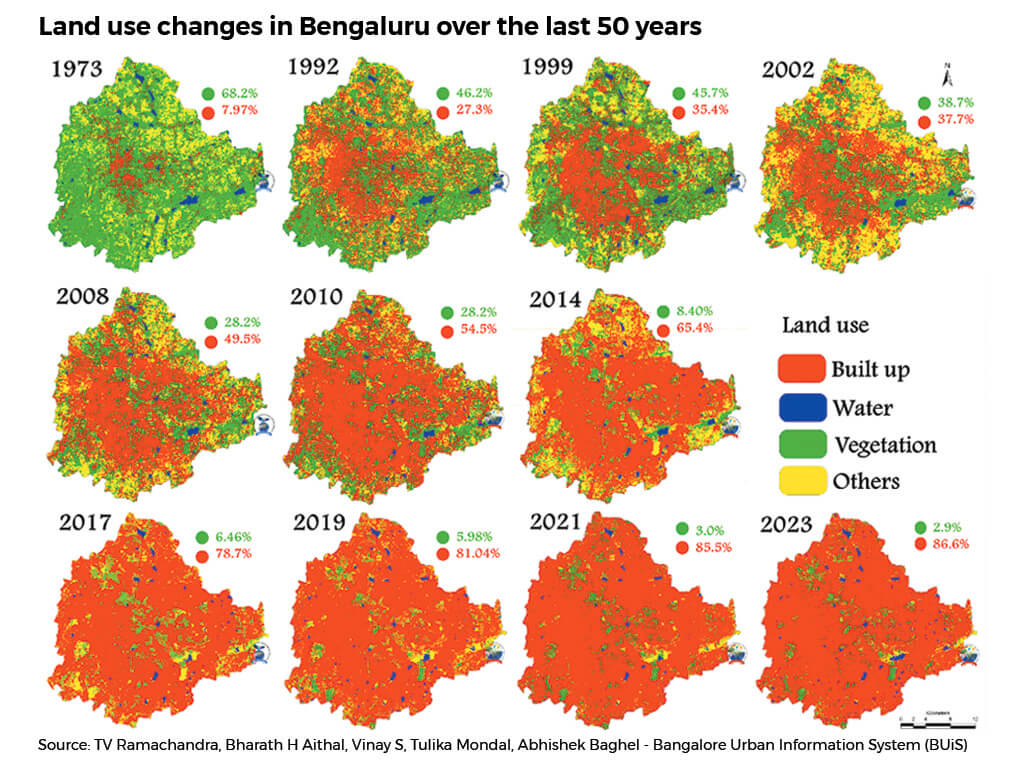

As the city grew rapidly (see built-up area in the maps above)[1], governments assumed they could get Cauvery water till realisation dawned in 2016-17 that there simply isn’t enough. By then, the Supreme Court had, in multiple rulings, allocated the Cauvery water to Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, and in Karnataka for irrigation and drinking. Bengaluru simply could not get more water.

Meanwhile, the growth trajectory did not stop. The expanding city swallowed[2] everything around it as the greedy and needy sold land to those who came seeking the city’s ‘great weather’. A few of us wrote about this, but in vain. The Lake Development Authority, I realised, had one bureaucrat whose mandate was to ‘beautify’ five lakes while 50 were being built upon and lost. The gullible bought more and more land.

Bengaluru’s water math has failed; it was bound to. It is an utter failure of planning. The local reservoirs, lakes and watershed areas were completely ignored because everyone believed in engineering solutions. This summer looks bad with some areas like East Bengaluru suffering some of the worst shortages but this is not only because of the failed monsoon in 2023. Number-crunching shows me that the potable water supply scenario is poised to enter negative territory even with normal or surplus monsoons in the future.

Bengaluru has water supply of 1,450 million litres daily (mld) from the Cauvery and a further 750 mld from it next year. Already, the massive shortfall – nearly half of the city’s requirement – is met by groundwater drawn from borewells. These are recharged with rainfall. If a year has less rain, the water table is recharged less. But there is another critical aspect – how much land is built upon. The more the concrete covering the land, the less water reaches the borewells. Multiple agencies have documented this through research, a good resource to know more is this report by Well Labs.[3]

Most new property developments outside the old city rely totally on groundwater and borewells. At least one-third of the urban area and most peripheral urban villages do not have piped water. The piped water supply has been lagging behind demand; it is an old problem, from the 1960s. At great expense, the Cauvery 90 kilometres south of Bengaluru was tapped and water pumped almost 1000 feet uphill to the city. When it rains there is water to pump from the borewells, when it fails the city is in trouble like it is now because the demand from borewells goes to 1,400 to 1,900 mld. Water cannot be extracted at this rate.

The fast growth in the last 20 years, led by the IT boom and ‘Silicon Valley’ stories, has been in areas that do not have piped water. People here are dependent on borewells directly or tankers supplying water pumped from borewells some distance away. People are apparently going to malls to use toilets because they do not have water at home. These areas should not have been built, to begin with, but building permits were given, industries set up, large corporate parks and gated complexes were constructed. Where was the piped water supply to any of them?

Authorities were warned of ‘zero day’

Bengaluru’s water demand forecasts and supply never met; this was worsened by the unplanned growth. The Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB) is good at showing the ‘big’ shortfall. It spends almost 80 percent of its revenue to pump water but knows that, soon, there may not be any more to pump. The problem is that it only estimates demand from ‘planned development’ while growth has been anything but that.

Till 2021, the estimated planned demand was 2,100 mld which is to be met by 2025 when Cauvery Stage V comes on. The unplanned demand is met by extracted groundwater. The Cauvery is fully tapped and cannot spare a drop more for Bengaluru. There is already a clamour from farmers that they need irrigation and, in the past, water thieves and protestors have damaged pipes that supply water to Bengaluru.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The authorities are aware of the crisis. The BWSSB knows exactly what the problem is because we are all using its data. Its website details the water problem and states ‘we don’t have a source of water for Bangalore’. So, here’s a government agency acknowledging that it cannot bring more water to the city. What more do we need to know except that planning is a total and colossal failure? Journalists have been writing for years, I did till 2009, warning of a ‘zero day’ when there will be no water. We are there now.

The monsoon dependence is set to worsen. When a monsoon failure makes the water problem more acute, there is over-extraction of groundwater which, in turn, will take three or four surplus monsoons to be replenished. In between, a bad monsoon can trigger a massive crisis given the unrelenting demand. The total demand now is more than 2,900 mld which the BWSSB had projected and ‘planned for’ in 2031 but, given the growth, the need may be 4,200 to 4,500 mld before that. The demand-supply gap is widening massively.

The BWSSB says it does not have any more planned supply. The city has no perennial water source to be tapped. Water from the Cauvery is fixed at 2,200 mld. Where is the nearly 1,500+ mld coming from by 2030? Borewells are already drying up. There has been no plan to even recycle most of the used water, the sewage treatment plants do not work at full capacity, and the authorities are short-thinking ‘it has rained today, so we don’t have to worry’.

Illustration: Raj Bhagat P

The ecology and the monsoon

Every bad monsoon from now will be a bigger disaster with less water in the Cauvery and less underground. Mega-surplus monsoons are needed to replenish the groundwater for the borewells. These cannot be regular; besides, they spell massive floods. The Bengaluru flood of 2022 became an international story.

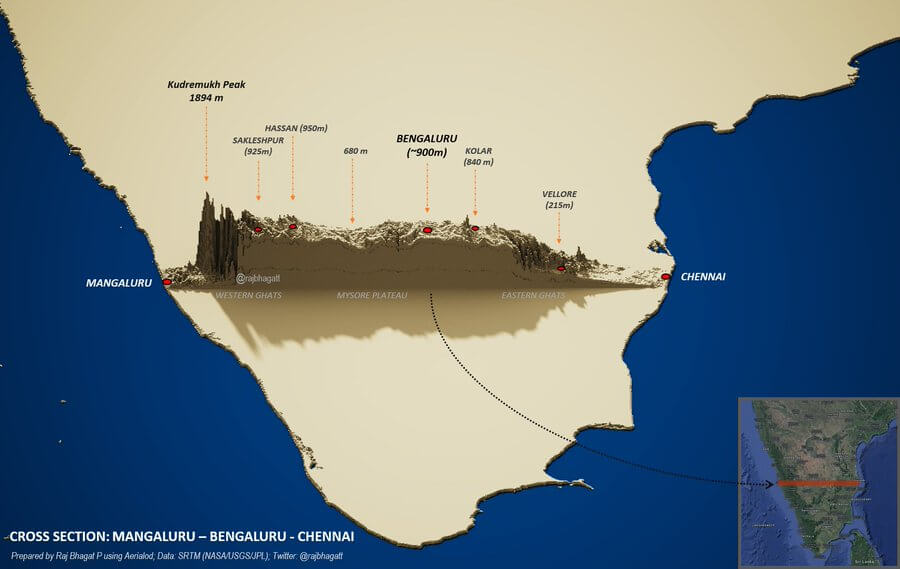

The floods are because all the floodplains and watershed areas have been built upon, roads are tarred, and footpaths cemented. The rainwater does not percolate below but just flows out flooding the low-lying areas. Bengaluru is unofficially a hill station situated nearly 1,000 metres above the sea level.[4]

With climate change and heavier intensity precipitation becoming the norm, the water problem will only worsen. People’s losses will mount. I know people who, for consecutive 3-4 years, have lost cars or paid heavily for repairs of cars submerged in underground garages running bills of Rs 1 lakh per car per year. The losses to business and the city’s economy are incalculable. The consequences of destroying the ecology are evident.

This is a problem in every city, whether in Delhi, Mumbai or Bengaluru because cities are not seen as part of a landscape with a functioning natural ecosystem. The heat is too high or there are recurring floods or epidemics where the water stagnates. Cities have become unhealthy to live in; Bengaluru cannot be an exception. However, its problems are unique and basic – lack of adequate water piped to more than half its population. The only other major city with such a problem, research tells me, is Cape Town. Even so, there is no city in India like Bengaluru – a city allowed to grow without planning for water.

The state and city governments have lost the plot; there is no solving of this problem. There is some talk of getting water from the Western Ghats but the hydrology data is sketchy, not much is known about losses in transporting water, such projects take time to stabilise before a pattern is established and to know how much water to draw. So, these are hardly solutions.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The course correction

There are, unfortunately, no shortcuts or quick fixes. Bengaluru authorities can look for more water sources or, better still, plan a new city near water sources which would be easier. But this may be wishful thinking. Even if a new city is planned, a set of measures have to be taken now for the city as it exists.

The authorities have to figure out a way to harvest rainwater at a landscape level on the Bangalore plateau, restore some of the lakes as urban fresh water reservoirs, save the existing flood valleys all of which together can potentially increase the water supply. They will also have to plan for bringing water to the city from another river system by 2050. The course correction is to stop giving permissions for new buildings till the city reaches water surplus status.

What can be done immediately is rainwater harvesting. It calls for a two-pronged effort – the water has to be harvested at the landscape level and also at individual household or a building level. The latter is not likely to contribute as much as the former. The landscape level harvesting needs open spaces to percolate and recharge the groundwater but all the land has been built upon. Where will this level of rainwater harvesting happen?

So, the option is to build a new city, maybe near rivers like Krishna or Tungabhadra which would also help the development of northern and central Karnataka. It would be cheaper and easier to set up a new city using the lessons learned from this failure in Bengaluru. We have not built new cities in India in recent history. Gurugram, NOIDA, Navi Mumbai are all offshoots of the existing large cities. Amaravathi, the planned capital of Andhra Pradesh, would have been a model for a greenfield new city but, unfortunately, it wrote its own death. India needs six new greenfield cities to be built to take the load off the top six cities today, including Bengaluru.

Trying to fix the water problem in Bengaluru now is like catching a running train; it will not work. There are many development issues but water is the most critical aspect of a city. Bengaluru’s failure should be a warning sign for all other cities in India. If you plan to live in Bengaluru long term, start answering this question now: where will I get water from in 2035?

Anand Sankar, originally from Bengaluru, is now a writer specialising in hydrology and rivers, and a social entrepreneur now based in the Tons River Valley, Uttarakhand, where he runs an NGO, Kalap Trust.