At the heart of COP29’s discussions in Baku, Azerbaijan, held earlier this month, the Mitigation Work Programme (MWP) emerged as a key factor for understanding the successes and limitations of global climate strategies. The MWP, established to operationalise the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C goal, aims to accelerate immediate emissions reductions. However, when evaluated in an Indian urban context, especially with respect to the urban poor, it shows oversights and unfulfilled promises.

In 2024, the MWP brought urban systems to the forefront, hosting global dialogues and investment forums, to address their significance in climate mitigation. These discussions highlighted the critical task of decarbonising existing urban systems while ensuring low-carbon infrastructure in unfolding ones.

Besides several differences, the negotiations in COP29 marked a rare consensus among developed and developing nations on the key role of urban systems in combating climate change. However, the MWP limits its text to “efforts to eradicate poverty” which leaves a large room for its interpretation while, importantly, keeping climate justice and social equity out of the mitigation dialogues. This will have critical implications for South Asian cities, as cities are where the impacts of climate change are felt most acutely—whether through flooding, heat islands, or resource scarcity—and yet, they are also where solutions can be most effectively implemented. Mitigation then risks being mal-mitigative, keeping the most vulnerable out of its reach and pushing them further to the margins due to ‘green’ infrastructure projects. (Rathore V. 2021 & YUVA, 2020)

The differences were steep when finance outcomes at COP29 were deeply disappointing, with climate finance to be ‘led by’ developed countries set at $300 billion per year by 2035—far below the $1.3 trillion that many in the Global South had called for.(Kumar S. and Mrinali, 2024) Without dedicated global public grants for urban resilience especially for urban poor communities—the goals of the Paris Agreement cannot be realised. Beyond this, the lack of clarity regarding how much funding will be allocated to mitigation, adaptation, just transition, or loss and damage—along with the uncertain positioning of cities in the priority list—leaves the future of the urban poor in a precarious and uncertain state.

Without clear financial commitments and priorities, the resources needed for equitable climate action in urban areas remain insufficient, and the urban poor are at risk of being left behind in the race for resilience and climate justice.

Illustration: Nikeita Saraf

MWP and its relevance for Indian cities

India exemplifies the paradox of urban growth in a climate-challenged world. Cities, which are responsible for 70 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, also house some of the most vulnerable populations. Nearly one in three urban residents in India lives in informal settlements, enduring a host of intersecting crises such as inadequate housing, exposure to climate hazards, and limited access to essential services like healthcare and education. (King R. et al., 2017)

Urbanisation in India is expected to increase by 40 percent by 2050, further straining already overburdened infrastructure and resources (Sarkar and Mehta, 2019). In this context, the urban poor—who are already disadvantaged—are often forced to bear the brunt of climate-induced shocks, exacerbating their vulnerabilities. This contradiction — where cities serve as engines of economic growth yet are also centers of extreme vulnerability — was glaringly under-discussed at COP29. This is particularly of interest for cities of the Global South, where 90 percent of this future population growth is projected (Urbanet, 2023).

With heavy spatial implications for mitigation strategies, city planning then becomes a key lever to guide climate action. While ideally cities should give up land for social and climate equity, this is easier said than done as Indian cities are layered with various competing and complex interests. Urban growth is being fuelled by smaller cities across India which present an opportunity to not repeat the unsustainable paths and mistakes of the metro cities; for this, spatial planning and urban form decisions are key tools to align with the demands of climate change.

However, let alone climate mitigation action, Indian cities are yet on a trend of real estate and market-driven development. The recent development plans for Guwahati and Panvel are analysed for climate mitigation through three key frameworks: Ecology, housing for the urban poor, and state planning Acts.

Guwahati Master Plan 2045: Missed opportunities

According to the 2011 Census, Guwahati Metropolitan Area had a population of 9.6 lakhs, which is expected to grow up to 38.6 lakhs by 2045. The Guwahati Master Plan 2045 was released for public suggestion objections in January 2024 which opened up a critical advocacy space to push for spatial climate mitigation strategies.

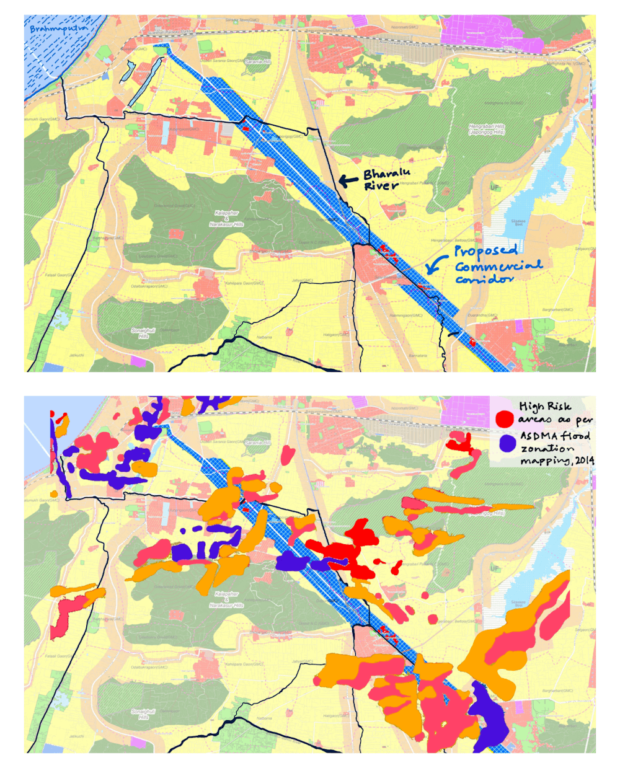

In August 2024, YUVA facilitated consultative processes with representation from NGOs, journalists, academicians, urban practitioners amongst others. A closer review of the Master Plan revealed jarring gaps and ‘mal-mitigative’ proposals in the Master Plan. Despite the city’s recurrent and worsening floods — aggravated by deforestation, reduced wetlands, and unplanned construction — the Plan promotes high-density commercial development along the Bharalu River, a natural drainage system (see Fig. 1) (Mahanta D., 2024). This not only increases flood risks but also threatens the survival of urban poor communities located along the riverbanks.

Source: Author

Adding to the problem, ecologically sensitive areas around lakes like Narangi Beel, a crucial wetland, are categorized as “vacant land,” opening up land for real estate. This ‘vacant land’ categorisation in the Existing Land Use plan has opened several ecologically sensitive peri-urban pockets for real estate consumption; which went from 43 square kilometres to 0 square kilometres in the proposed Master Plan. This short sightedness in spatial planning risks cities’ capacity to mitigate climate risks.

Further, the approach of the Master Plan to residential land allocation underscores a significant disconnect in addressing housing equity and climate change mitigation. While residential land has seen an increase of 31 percent, there is no sub-categorisation for public or affordable housing; despite significant mentions in the city Development Control Rules. This leaves critical housing needs for vulnerable populations, including the 99 notified and 118 non-notified slums identified in the report, entirely unaddressed.

The legislative framework compounds this issue. The Assam Town and Country Planning Act, 1959, last amended in 2022, does not incorporate mandates for climate mitigation in spatial planning. The Act restricts itself to outlining a general land-use plan, zoning, transportation, and public utilities, failing to address the critical need for climate-resilient city planning. In doing so, it neglects to integrate spatial mandates that could mitigate urban climate risks, such as preserving ecologically sensitive areas or ensuring housing policies prioritize low-income communities in safe ‘hazard free’ locations.

Panvel Development Plan 2024-44: Critical gaps

Panvel city, located adjacent to Mumbai, according to the Panvel Development Plan Report is projected to host 12 lakh residents by 2034. Its proximity to Mumbai drives its land politics which are fractured, governed by five Special Planning Authorities (SPAs), resulting in splintered and often conflicting urban development strategies. This also hinders a holistic climate-informed planning for the entire city, leaving fragmented ‘land parcels’ across different planning authorities’. From July to September 2024, YUVA facilitated public consultations across multiple stakeholder groups where gaps in the proposed Development Plan (DP) 2024–44 were analysed.

The analysis reveals a troubling trend: Approximately 72 plots, which are located beyond the hazard line, in alignment with the Coastal Zone Management Plan 2019 and some of them in Reserved Forests, have been earmarked for ‘residential use’. This opens ecologically sensitive areas for ‘development’ that are critical for climate mitigation. Much like in Guwahati, Panvel DP also pushes for a massive 38 percent increase in residential growth, which stands in stark contrast to the meagre increase in public amenities —from just 4.2 to 6 percent. Beyond mis-categorising vacant land, this disparity highlights the failure to plan for the essential services required to support such a drastic population surge, especially in the face of climate change.

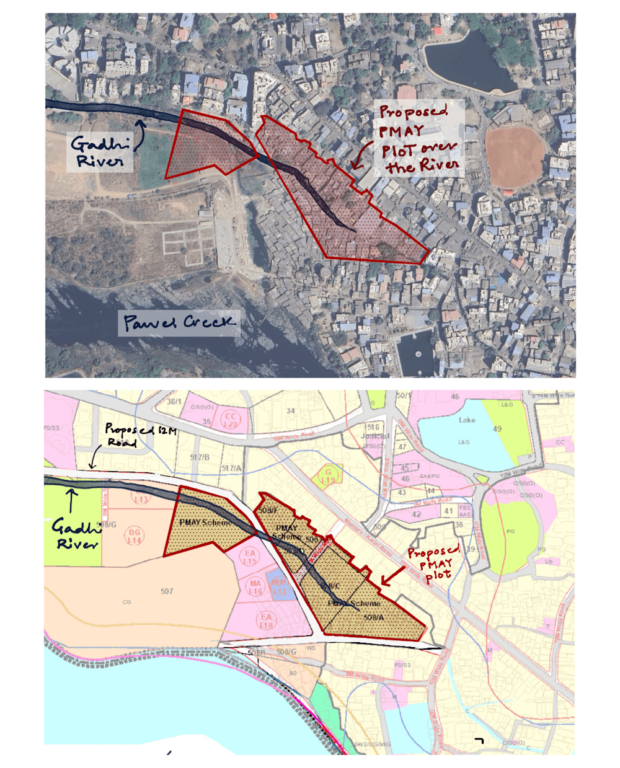

Another alarming example, which is similar to other such proposals in the DP, is the proposed housing allocation for the urban poor, that are located in a high-risk climate hazard zone. For instance, a Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY) earmarked plot,lies in a flood-prone area near the Gadhi River and Panvel Creek, where construction is typically restricted due to significant flood risks. A Public Interest Litigation (PIL) filed in 2023 has highlighted that the project has bypassed essential environmental clearances (PNT Bureau, 2023).

Compounded issues emerge in the Maharashtra Town and Country Planning Act of 1966, amended in 2015, which partially addresses climate risks by proposing flood control and river pollution prevention measures. Despite clear recognition in the Act, its spatial implications are not adopted in Panvel’s DP. The Act also fails to account for other climate hazards such as urban heat islands, coastal erosion, and water scarcity that have severe land allocation requirements for climate mitigation.

While the analysis opens up several points for scrutiny, the framework used for both cities covers spatial planning through the lens of climate and social justice. As many Indian cities revise their DPs, this approach offers a simple framework for assessment.

Going local to global

A framework by Local Governments and Municipal Authorities (LGMA) Constituency charts out a road map for going local to global and provides an overview for institutional engagement on climate action. Their study stresses that the global climate framework needs to not only set ambitious goals but also ensure that these goals translate into practical action at the local level, where climate impacts are most felt. Global initiatives like Coalition for High Ambition Multilevel Partnerships (CHAMP), C40 Cities, United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG), and Local Governments and Municipal Governments Authority (LGMA) stress the need to empower local governments like ULBs for climate solutions. This, when in the Indian context, outlines several opportunities and challenges.

India’s climate action plans, starting from Nationally Determined Contributions to national, state and city action plans are key aspects for shaping the country’s response to climate change. However, these plans often run in parallel to the response of Urban Local Bodies to climate action. Further, in Indian cities, multiple decision making bodies exist—including ULBs and their line departments, parastatal agencies, and the recently institutionalised climate cells. Each follows its own approach, often shaped by political influences, which leads to fragmented and inconsistent efforts in addressing climate action. To move forward, a stronger coordination and synergies between these different decision-making bodies is required. This also entails capacity building of ULBs for effective response to climate challenges at the local level.

In Indian cities, where engagement on climate action with local governments is still evolving, several civil society organisations (CSOs) are recognising the intersection between climate action and social justice. There is a pressing need for grassroots CSOs to humanise global dialogues, like COP, by grounding them in local realities. Through its work on over nine city Development Plans, including those of Panvel, Guwahati, Navi Mumbai, and Vasai Virar, YUVA has been bridging the gap by integrating climate-informed, socially-just planning and advocating it at global dialogues such as MWP. At grassroots this involves facilitating dialogues between communities and local governments, while also developing popular educational materials to support public consultations and advocacy.

Moving forward, COP29’s finance failures for the Global South and the lack of clear finance commitments towards cities, signals a missed opportunity. Without targeted public grants for cities and urban poor, urban resilience initiatives sideline the very communities that are most at risk. Yet, even if the financial commitments were met, the question of how cities align their spatial planning and land-use decisions to advance climate action equitably remains unresolved. Addressing this disconnect requires a paradigm shift in how cities approach land use and urban development. Spatial planning should thus recognise safe public housing and amenities as key mitigation strategies, while also amending state acts to align with climate action.

As the world confronts a rapidly changing climate, COP30 in Brazil next November must take a hard look at cities as crucial opportunities for climate action. It must bridge the gap by ensuring that public grant based finance by developed countries is not only available but also directed toward cities, with a particular focus on the urban poor.

References:

- Mahanta D. (2024).‘Guwahati’s Bharalu River turns into breeding ground for disease amid hue & cry. Guwahati Plus.

- King, R., M. Orloff, T. Virsilas, and T. Pande. (2017). Confronting the Urban Housing Crisis in the Global South: Adequate, Secure, and Affordable Housing. Working Paper. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute. Available online at: www.citiesforall.org

- Kumar S. and Mrunali. (25 Nov 2024). We have seen what you have done”: India accuses COP29 presidency, UN of “Stage managing” decision. The Wire.

- PNT Bureau. (9 Nov. 2023). Bombay High Court to hear PIL on PCMC’s handling of Panvel slum rehabilitation project. Prop News time.

- Rathore, V. (2021, October 13). Behind the “Green” rationale of evictions. THE BASTION.

- Sarkar, Sandip, and Balwant Singh Mehta. (19 Dec. 2019) Infrastructure and Urbanization in India Issues and Challenges, in Guanghua Wan, and Ming Lu (eds), Cities of Dragons and Elephants: Urbanization and Urban Development in China and India (Oxford, 2019; online edn, Oxford Academic. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198829225.003.0014 , accessed 26 Nov. 2024.

- Urbanet. (2023, December 19). The world urban population | Infographics. Urbanet.

- Youth for Unity and Voluntary Action. (2020). The Evicted Republic: Forced Evictions and People’s Right to Adequate Housing. City Se. Mumbai: India.

Dulari Parmar, Lead for Climate Justice at Youth for Unity and Voluntary Action (YUVA), works to advance climate-just cities by integrating grassroots efforts into spatial planning. She leads advocacy at city and state levels, with growing contributions to national and global platforms. Representing YUVA in the Urban Transformation Platform—a consortium of grassroots organizations from India, Bangladesh, and the Philippines— she seeks to amplify urban poor issues in global processes.

Cover illustration: Nikeita Saraf