More than a hundred years ago, Sir Patrick Geddes, urban planner, sociologist, botanist, geographer, and educationist, submitted his development plan of Indore – possibly the first scientifically made urban plan in the then British India.

At a time when “urbanisation” and “sustainability” were unheard of concepts, Geddes’ expansive plans for Indore, one of Madhya Pradesh’s largest cities, were drawn on the lines of coordination of man with environment which he described as the new “humanism”. The versatile Scottish urban planner designed Indore by putting people at the centre of the planning process. But the Indore of today is far from Geddes’ plan or principles of planning. The haphazard constructions, the disappearing water bodies, neglected heritage structures and depleting trees have robbed the city of its old charm as well as the chance to build with nature.

Although I spent all my life in Indore, I did not know much about Sir Patrick Geddes till about a decade ago, except for a small reference in a book on urban politics in India by an American author. But that had to be corrected, I set out on the Geddes mission.

Sir Edwin Lutyens (1869-1944) who designed Delhi and Le Corbusier (1887-1965) who planned Chandigarh, continue to be resurrected in public memory through references to their work. But Sir Patrick Geddes, a Knighted Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (1854-1932), a polymath who straddled fields of biology, geography, sociology, and town planning, and his work in India remain quite unknown except for a select group of people.

This, despite the fact that the brilliant scholar helped plan or design many Indian cities and towns — some fully, others partially. The list includes Baroda, Calcutta, Indore, Lahore, Lucknow, Nagpur, and Patiala and some replanning or extensions of cities such as Ahmedabad, Amritsar, and Bombay. Geddes wrote nearly 50 basic urban planning reports for Indian cities in a span of merely five-six years, from 1914 to 1919. Geddes was in his early sixties when he was working on the Indore Plan and often stayed in the city while completing his report in 1916.

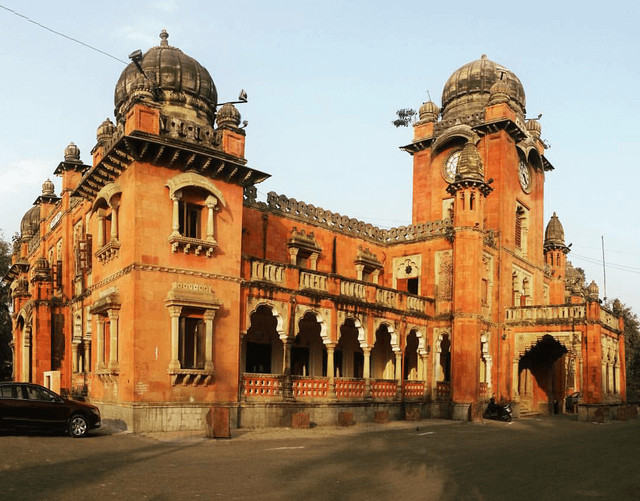

Photo: Creative Commons

The grand princely state

Geddes came to Indore after stints in other cities including Bombay and Baroda. “The circumstances of Indore, however, was not particularly favourable for an experiment in Geddesian civic reconstruction,” wrote Helen Meller in her book Social Evolutionist and City Planner, “The Maharaja Holkar, Tukoji Rao III, was no reformer like the Maharaja Gaekwar. The city was roughly the same size as Baroda, being 93,091 at the 1921 census. But it has few buildings of architectural merit, and its plan lacked the style of Lucknow or Baroda. It consisted of three main areas: the old congested quarter of Juni Indore, which had been pillaged and razed to the ground in the eighteenth century; the modern city and suburbs; and a developing industrial town. What it lacked in elegance it made up for in space as it covered an area of five square miles.”

Indore, like most Indian cities, was once a beautiful, green, and a well-planned city. Called Shab-e-Malwa, its heritage buildings stood out magnificently, its big old trees provided shade to people and animals, its broad roads were regularly washed, its parks were full of children, and its breath-taking lakes kept the city cool during summers. As the city expanded and developed, it changed. More vehicles on roads, unplanned construction across its expanse, rapidly dwindling number of trees, the land mafia’s nexus with politicians and officials, shortage of water sources, noise and the ever-increasing pollution have all impacted the city adversely. Did Indore miss a trick in largely ignoring Geddes’ plan which, in keeping with his ideas, advocated city making in step with nature and for people?

Today, when India is rapidly being urbanised, Geddes’ principles of building and designing cities have become all the more relevant. They matter to Indore because the city had a head start with his plans. Contemporary urban planners, however, do not think like Geddes whose approach to town planning was people-centric and nature-oriented. While Delhi still respects the Lutyens zone and the rules associated with its construction, it is quite surprising that there is hardly any trace of Geddes in Indore.

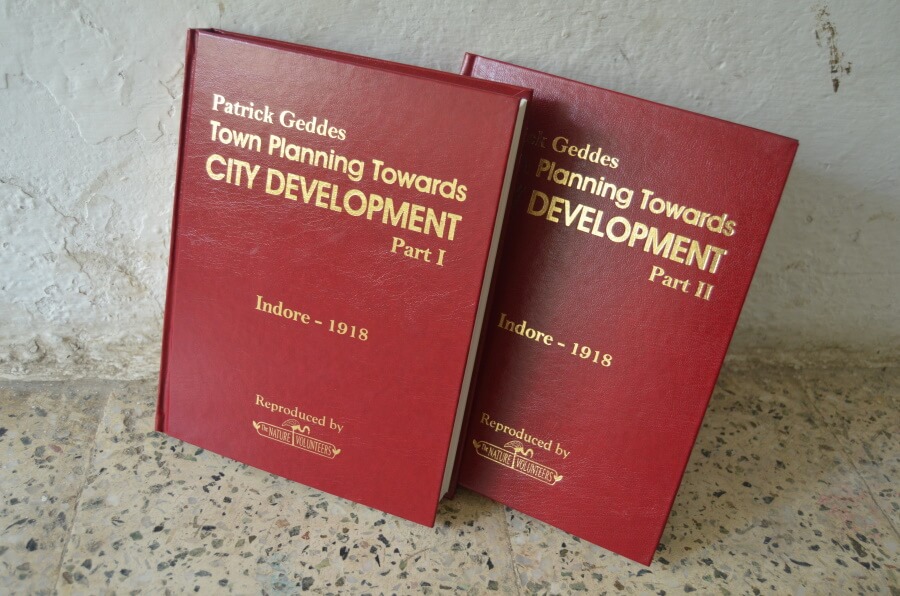

‘The Nature Volunteers’.

Photo: Bhalchandra Mondhe

Bringing the lost master plan into public domain

It is quite ironic that discussions about Indore’s urban plan and development – as the land mafia took control of private and public lands, as citizens and NGOs tried to save its heritage – barely made a mention of its early and unique master plan that Geddes had left behind. Being one of the major commercial hubs of central India, Indore needed a master plan but there was a blank about Geddes and his ideas for the city.

Sometime in 2012, my friend and journalist Abhilash Khandekar, who is also the vice-president of The Nature Volunteers, a group that I started to conserve the city’s natural heritage, and I realised that the first original urban plan of Indore drafted by Sir Patrick Geddes, was about to complete 100 years. Even the most aware and knowledgeable citizens in Indore knew little of this historic document.

The Nature Volunteers (TNV) began looking for the original Geddes plan so that we could study it and bring back focus on the need for scientific urban planning. Unfortunately, the two-volume report submitted to the Holkars by Geddes in 1918 could not be found in the official records. This only fuelled our resolve to reproduce the original plan on the occasion of the historic document’s centenary, and reorient planners and others in the city towards this kind of urban planning.

As per records, Geddes carried out various works for Tukojirao Holkar between 1915 and 1918. Using his scientific approach and wisdom, he worked on historical and economical studies as well as plans to solve urgent town planning and urban hygiene problems of the era.

I finally managed to lay my hand on the original report. It was time to bring the plan into the public domain. This appeared to be an insurmountable task but we somehow reprinted and produced the two volumes of the plan as an attractive two-book set.

At TNV, we decided to take help from the Indore General Library, Abhyas Mandal which is an active socio-cultural organisation, and the Mahanagar Vikas Parishad throughout the long and tedious process of reproducing the 100-year-old plan. All of them gladly agreed to become a part of this monumental project. We did not seek monetary support from them, but only wanted them to realise the importance of this work and spread information about the Geddes project among Indore’s citizens.

When I began searching on Geddes’ work, I came across a book in a library in New Delhi which gave a fantastic account of his varied work. His reports were unique, displaying his thinking of keeping people at the centre of his urban planning process. In what is common to most of his town planning work in India, Geddes always studied the society, surveyed the local land including the roads and wells and trees, assessed needs of the local people, and followed a sociological approach to plan the city – a much-needed approach even today to save the environment, our culture and heritage.

Another reason for us to reproduce Geddes’ Indore plan was the brilliant book, The Plan of Chicago, by Carl Smith (2006) which talks about Daniel Burnham and the remaking of the great American city, and is arguably among the influential documents in the history of American urban planning. The book reveals the Burnham Plan’s vital role in shaping the way people envisioned the cityscape and urban life itself, and how it continues to influence debates about a vibrant, habitable urban environment even a century later.

What, however, was more impressive, was the beautiful publication of the old plan in the book form by Smith, as well as the association of numerous public institutions of Chicago with the project. TNV attempted to do something similar by reviving and reproducing the 100-year-old Geddes Plan for Indore. And through this, we wanted to bring back the focus on the scientific urban planning approach given the rapidly deteriorating state of the city and the lack of seriousness about this in most quarters. We hoped, that in the centenary year of the Geddes Plan, we could reignite a constructive debate on Indore’s urban planning and its future.

Heritage properties lost in urbanisation

Among its notable characteristics lost in the new urban development is Indore’s built heritage that is either crumbling and forgotten or cynically built over. Only the renovated Rajwada, a seven-storey palace built by the Holkars nearly two centuries ago, is a reminder of the grand royal past. The Shiv Vilas Palace, next to the Rajwada, is lost amid the encroachments, shops, crowds, and cacophony. The popular Harsiddhi temple, Hawa Bungalow and Chhatri Bagh are mired in neglect and apathy.

Not only the built heritage but also Indore’s natural areas are at stake. A photo of elephants bathing in the Saraswati and Kahn rivers shows the city’s rich natural resources as they used to be. The Geddes Plan had recommended, among other micro things, preserving the city’s old wells and water bodies.

“Since all these Mill wells are ample and excellent, I strongly recommend a survey of the existing wells throughout the city, of which some are productive, and others may again be made so by cleaning,” reads Town Planning Towards City Development, A Report to The Durbar of Indore, by Patrick Geddes, Part 1, 1918. However, the water bodies and ancient wells have been reduced to nullahs with rapid urbanisation. There is enough to say that the city failed to conserve its natural water resources.

“It is interesting to note that as early as 1918, Sir Patrick Geddes mentioned the importance of wells as reserve sources to cope up against the interruption in piped water supply and demand challenges of urbanization. While Indore was known for lakes, open wells and Bawdi/Baoris that met all the water needs before 1984, they are now neglected and polluted…(however) it is to be noted here that a number of wells have got converted to solid waste dumping pits and the Talaos have been converted in to liquid waste dumping due to negligence and lack of maintenance,” reads the report by the Environmental Planning and Coordination Organisation.

Photo: Creative Commons

Call to revive lost glory

Although Geddes’ town planning work has been widely studied – even praised – for its holistic approach to building cities, it has received its share of criticism too. Meller noted in her book that “…the Indore Report is a greatly flawed work because of the character and style of the author… Yet, Geddes’ passionate commitment to put people first in planning comes across with great emotional force. Geddes did not perceive, though, that his work on Indore did not add up to a town plan unless the reader accepted unconditionally his advocacy of the doctrine of civic reconstruction.”

It is possible to pick the Geddes Plan apart today, some parts may not even be relevant any longer, yet it merits our attention. It is the responsibility of Indore’s planners to dive deep into it, understand its approach and incorporate that into modern urban planning. The Smart City tag of Indore will not be of much importance if the people here do not have the right to clean air and water.

Geddes has been re-introduced to Indore, it is now up to the powers that be to adapt his principles in the interest of the city’s future.

Bhalchandra Mondhe is an Indore-based well-known artist, photographer, painter, and environmentalist. A recipient of the Padma Shri award in 2016, Mondhe co-founded The Nature Volunteers Club, which he runs as its president.

Cover photo is from Bhalchandra Mondhe’s collection. Chhatri Bagh along the Kahn river used to be a bathing spot for elephants. Now, the river has dried up, and an artificial lake and fountains have been made at the tourist spot.