In August 2024, torrential rains caused the Musi river – otherwise demure and neglected, often dry — to swell. The rising waters inundated houses, bus depots and low-lying areas across Hyderabad. Although it was not the first flood for the people living along the Musi, they panicked as water entered their houses and partly submerged their meagre belongings. The story repeated in 2025. Many recalled similar havoc during the floods of 2020 too.

The banks of the Musi, along its 55-kilometres in Hyderabad, have been occupied by the people that the city would like to forget – informal workers and others on whom it depends. The various bastis and settlements along the Musi, many of them unauthorised, show the connection people had with the river. The river that once sustained life in the city steadily turned into an ignored mass of filth and waste. When ambitious plans were made and executed for the river, targeting the people and slums to be cleared, farmers had to look for an alternative livelihood, washermen had to fetch clean water from elsewhere, and others wondered how they would make a living 15-20 kilometres away.

In 2022, the National Green Tribunal ranked the Musi the ‘most polluted river’ in Telangana, based on a state pollution control board report.[1] The highly polluted Musi water has affected the paddy and vegetables grown on the river bank. The rising incidence of poultry diseases and milk production have directly hit livelihoods. Traditional occupations like washermen, fishermen, weavers, pot makers, and toddy tappers have been adversely affected too.[2] People have been here long enough, legally and otherwise, to reminisce about the time when the Musi waters were pristine. Their time near the river now seems to come to an end.

Sheikh Mujayat, 61, driver

Shankar Nagar

“My family and I have been living here for 40 years. There were fewer houses earlier and the river bank was filled with grass. We built a house in 1990. Our house was close to the river but did not face floods until 2024. Even if there was a lot of water in the Musi, it never reached our homes. I incurred losses during the floods. Everything was spoiled. Not a grain was left.”

“This area was beautiful because of Musi but now we live in fear of the floods and the government’s action. My three children, three sons and one daughter, grew up here. My small grandchildren now think the river is a drain. We have water and electricity, but now this is called a slum and the government is demolishing houses built with hard-earned money. A total of 297 houses were demolished in 2023. The government is giving houses to the displaced but deciding this based on electricity meters. Extended families live in one house which has only one meter. The small house they get from the government will not accommodate the entire family.”

“We used to live along the Musi but where is it now?”

Syed Bilal, 38, activist

Shankar Nagar

“I am a local and I became an activist looking at the condition of the Musi. The huge river was contained in a small canal a few years ago. The government built ‘rubber dams’ which accumulated more waste. These projects are destroying the river. The water carrying capacity of Musi has been lost. The government talks of beautification but the river is still filled with industrial effluents and it blames the people living along the Musi for littering. This is wrong. The locals are trying to preserve the river and the government is hell-bent on destroying the river.”

“As soon as a new government takes charge, the beautification project is revived and becomes a means to make money. Around 1,000 families live on the stretch from Golnaka to Shivanand Hotel. We bought land from the paddy farmers and built houses. Although we have land documents, the government says we have encroached on Musi land. In January, we met the officials of Asian Development Bank, which is funding the riverfront development project, and placed our demands. We want the Musi cleaned but without displacing the people.”

Asifa Begum, 50

Shankar Nagar

“I grew up here and got married here. Then, the Musi was the centre of our lives. We used to bathe and wash clothes in the river, and take an afternoon nap on the river bank. We even drank the Musi water. It was beautiful. As the city expanded, we saw the river deteriorate and become polluted. What is left of the river now?”

“We can’t even understand what is happening. One day, houses were demolished here. We are looking at an uncertain future. One thing I am sure of is I want to live here. I do not want to be shifted like they did to some families. They (government officials) gave me an Aadhaar card, we got water and electricity here. Now, how can they ask us to move away from the river? We want the government to clean the river and not move us from here.”

Pyari B, 70

Domestic help

“My entire life has been spent along the Musi. I have a small house that’s crumbling now. I do not have any option but to work in the nearby houses. I earn around Rs 3,000 a month but spend most of the money on medicines. The polluted river has made our lives difficult. We live near it and breathe in the smelly air. During the 2023 floods, houses were submerged and the water reached three-feet high. We had never seen such massive floods. Even after the water receded, there were no basic amenities. We were left to fend for ourselves. Diseases spread soon after.”

“I live in constant fear now as the government has started demolishing houses. My neighbours’ houses were razed in 2023 and the debris is still lying along the Musi. The river has been destroyed. But we will not shift from here. We will unitedly protest if the government asks the remaining of us to vacate this area. We want to live here.”

T. Sushila, 52, runs a corner store

New Tulsi Nagar basti, Ameerpet

“I have been living along the Musi for the past 25 years. Although my family did not depend on the river for livelihood, we were happy living on the river bank. We even built a house here 13 years ago. My children – a son and a daughter — played on the Musi river bank. We were safe during floods too. But now the talks of the riverfront development is giving me anxiety. My neighbour’s house has already been marked to be demolished. My family and I have toiled hard to build our house and raise our children. My small shop is also running well. We do not want to shift from here. I will fight if asked to shift. The entire basti people feel the same.”

Laxmi Parvathi, 35, waste collector

Shivaji Nagar

“I am from Kurnool in Andhra Pradesh. My husband, our three children and I came to Hyderabad in search of work. We live along the Musi river because the garbage segregation and sorting space is here. There are around 100 makeshift houses here. When we came here 30 years ago, the river was not so polluted. Now, the river is hardly visible except in the monsoon when it flows continuously. For the past few years, we have been living in fear as the water reaches our homes. It wreaked havoc in 2025 and although our makeshift homes are on a higher ground, water entered houses and submerged everything. We had no food and lost everything. NGO workers provided us with the essentials. Now, whenever it rains heavily, we are scared of floods and snakes — and move to the road.”

Musi Shankar Anna, 50, farmer and village sarpanch

Edulabad

“There used to be many farmers along the Musi. Many still rear cows and buffaloes but the toxic grass along the river and the contaminated water have affected our cattle. Farmers used to get 10 litres of milk but hardly get 2 litres now. We got to know of many miscarriages in animals as well as women. The Musi water is totally toxic. In fact, it is not water, it is only chemicals. Decades ago, we used to drink this water but now even fish do not survive. The industries have polluted the water; if the companies are allowed to operate this way, then pollution will worsen. The pollution control board doesn’t care.”

“During YS Rajasekhar Reddy’s government, Rs 344 crore was spent on sewage treatment plants. But we, the people of Moosi Paravakkam, gave memorandums to the government and pollution control board officials that we didn’t want a sewage treatment plant and instead demanded an effluents treatment plant. Still, they set up sewage treatment plants; some work, some don’t. We seem to have lost the right to live. I am asking the government to give us the right to live.”

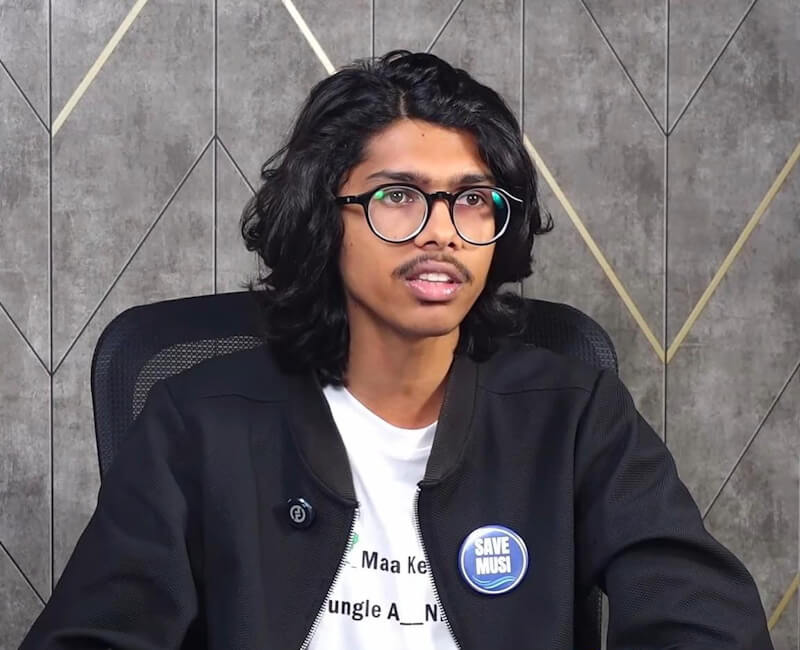

Ruchith Asha Kamal, 20

Associated with Musi Jan Andolan and works with Climate Front Telangana

“I have been associated with Musi Jan Andolan since 2024. It was started after the government’s demolition measures in 2024 when the state tried to demolish people’s homes in the name of ‘encroachment’ to carry out the riverfront project. The counter movement started then which I joined. I also work with a group called Climate Front Telangana, the local chapter of a youth-led movement for environmental justice. As a part of our work, in December 2024, we initiated a documentation of the Musi River in the context of the demolitions and the riverfront project. After this, at the press conference, we declared that the river needs rejuvenation, not concretisation, and announced the Save Musi Movement.”

“The Save Musi Movement is a larger youth collective and youth-led movement that started doing clean-up drives. Since January 2025, we have done multiple clean-up drives involving more than 250 young people. In fact, people from outside Telangana also showed interest. At the Musi riverbed, mostly at Chaderghat, we tried to pick up the trash and hand it to the Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation. Alongside, we have had consultations with the basti people and supported them in whatever way possible. There has been a crackdown on us. One of our members, Bilal bhai, was detained by the police but later released.”

“We have been organising creative ways of making people aware about the Musi – a Musi Museum created from the waste collected during the clean-up drives, tracing down the historic projects along the river, visually presenting these with money spent. Recently, when the Asian Development Bank officials came for a field visit, along with citizens from affected areas, we stepped in to request a meeting during which we demanded to know details of the riverfront development project and the documents that our government had given them. The ADB loan had not been sanctioned, contrary to what the government was saying.”

“We will strengthen and scale up our movement. We are demanding two things. First, respect people’s opinions and hold consultations with the people affected by the Musi riverfront project because they are also the stakeholders. Second, irrespective of the rejuvenation plan, people have historically demanded water purification of the Musi River. Government bodies contribute to so much pollution. The water and sewage supply board is a major polluter because it releases 60 percent of the sewage from the city directly into the river. Curb the pollution, then we can see what beautification is needed.”

Shobha Surin, currently based in Bhubaneswar, is a journalist with more than 20 years of experience in newsrooms in Mumbai. An Associate Editor at Question of Cities, she writes about climate change and is learning about sustainable development. She was most recently a Fellow of the Earth Journalism Network working on the issue of Non-Economic Loss and Damage suffered by communities due to climate change in Odisha.

Cover Photo: Malakpet Railway Bridge on the Musi River, Hyderabad; Credit: Shobha Surin