The Musi River is about 250 kilometres long, of which roughly 55 kilometres flow through Hyderabad, a city of nearly 15 million people. The river has played a central role in the history and life of Telangana’s capital. From the founding of Hyderabad onward, the Musi shaped the city’s growth, livelihoods, and everyday practices. More than just a source of water, it carries Hyderabad’s shared memories and heritage.

For much of its history, the river acted as a natural boundary, separating the older parts of Hyderabad from newer areas, and influencing how the city developed socially and spatially. Over the past years, studying the Musi across different historical periods, as well as the origins of its various names, helps reveal how people have understood and related to the river over time.

The rivers in the Deccan are not perennial. The Musi is described by travellers as ‘a mere trickle during the summers and a raging torrent during the monsoons.’ The rivers swell during the monsoons and contract during the dry seasons. Historic settlers were vary of the floodplain areas, restricting its use for seasonal agrarian use. Old photographs and descriptions describe cucumber and pumpkin farms in the riverbed in Hyderabad city limits, while some sections had temporary informal settlements which would flood every monsoon. The banks and the riverbed were accessible during non-peak seasons for locals to bathe, collect drinking water, water and graze their animals in the grass beds and farm crops on the banks.

Early Settlements

As per epigraphic and archaeological evidence, the oldest civilisations on the Musi date back to the 5th century, when the Vishnukundinis built their capital on the south bank of the river at Indrapalanagar. The power centres on the Musi eventually moved westwards to interior Telangana a millennium later, at Golconda on the north bank further upstream. Historically, as with other rivers that nurtured human settlements, the story of the Musi too is woven with the ones that came up along its banks; of these, the most significant one was the city of Hyderabad.

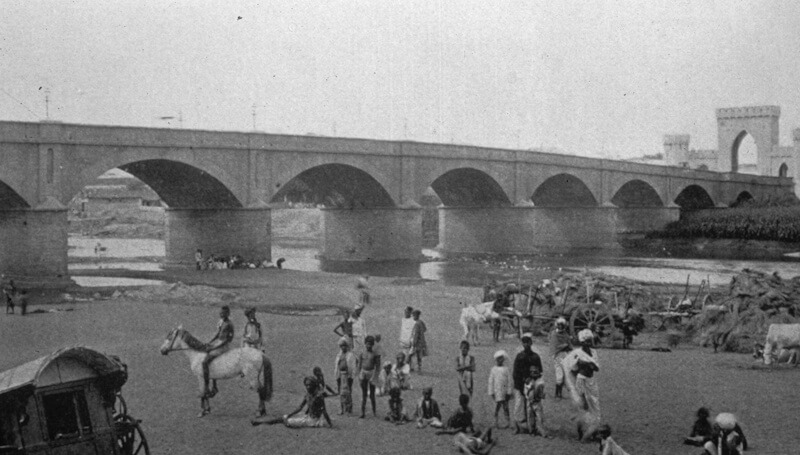

The city was founded in 1591 by Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah, the fifth Sultan of the Qutb Shahi dynasty, on the southern floodplains of the river. The Musi had a dual role: It served as a defensive moat as well as a water source once small check dams were built. The Musi of the old Hyderabad had a riverfront with grand palaces, shamshaan ghats, Sati mounds, dhobi ghats and even slums. But it also put limits on the city; it could not expand northwards until the late 19th century when new bridges were built across the water to connect the north and south banks of the river.

Photo: Deccan Archive

When the Qutb Shahis (1518-1687) found the fortress of Golconda overcrowded, plans were drawn up for a new city on the trade route between Surat and Machilipatnam. A bridge was first thrown across the Musi at Karwan, now known as the Puranapul (1565) and eventually the Charminar (1591) marking the beginning of a new planned city. The south bank of the river demarcated the northern extent of the city of Hyderabad.

The importance of the Musi for early Hyderabadis can be assessed from the fact that the only rivers in the subcontinent to be named after Abrahamic prophets are the Musi (Moses) and its tributary Esi (Jesus). The supposed etymology of the name “Musi” in the Telugu language stands for ‘Lush Paddy Fields’. Despite this ambiguity, the popular local account that the river derives its name from the convergence of its “Moosa” and “Esi” tributaries is widely accepted and forms a significant part of the river’s contemporary nomenclature.

Rituals and sacred culture

Like all other rivers of the Indian subcontinent, the Musi also had several cremation grounds called masaans along its banks. The largest one was at the Sangam (the confluence of the Musi with its tributary Esi) at Langar Houz, where Hyderabadis would gather to perform a holy dip or dupki to absolve their sins during Karthika Pournami. This tradition dating back from the Qutb Shahi period continued until the 1950s, when it was stopped due to extreme pollution. In Hyderabad, several historical temples dot the Musi river bed like the Chandulal Sivalayam at Puranapul, Kasi Bugga temple at Kishanbagh, and several others built to withstand the annual monsoon deluge. The river also had multiple Sati Ghats which were active until the practice was banned.

The flower festival of Telangana, Bathukamma which involves the ritual immersion of a floral representation of the folk goddess Bathukamma in local waterbodies, also unfolded along the Musi. Women in traditional attire danced at the banks and completed the immersion during the post-monsoon Navratri season. At the end of the festival, the Musi would be covered with a sheet of colourful flowers. This ritual underscores the river’s role in the city’s spiritual life, communal bonding, and cultural continuity.

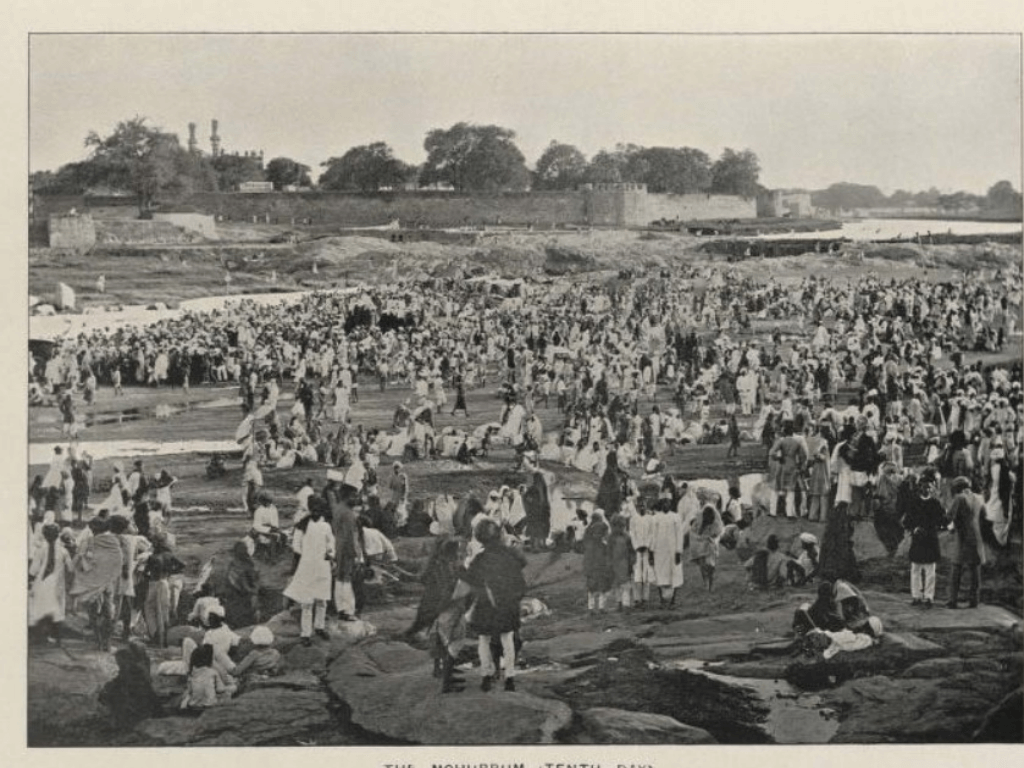

Medieval Deccani cities had open spaces for observing Muharram practices called Karbala Maidans. Today, people remember the Karbala Maidan of Secunderabad on the northern banks of Hussain Sagar but the one in Hyderabad, on the Musi, is largely lost from public memory. The annual Muharram procession would culminate in the Musi with the ritualistic washing, or thanda karna, of the alams and other paraphernalia, in the waters – a spectacle in which the city would participate, a syncretic tradition that defined the relationship of the people of Hyderabad with the river beyond religious affiliations.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Memory of the Tughyani

The Great Musi Flood of 1908, locally referred to as the Tughyani stands as the watershed moment in the urban history of Hyderabad. As the waters in the Musi rose 20 feet over the Afzalgunj Bridge, the river in fury took the lives of an estimated 15,000 people in a single day. In its aftermath, the City Improvement Board was set up to resuscitate the city. India’s well-known engineer M. Visvesvaraya, who headed the post-flood rejuvenation of Hyderabad, insisted on the permanent damming of the river at Gandipet (Osman Sagar and Himayat Sagar) and the construction of a public riverfront with stately buildings and parks on both banks.

Slums, or what remained of them, were cleared and people were relocated to model colonies away from the flood plains. Markers for High Flood Level were erected on all major public buildings as a memorial to the great flood and also to guide future planning of the city. Several activities in the riverbed were prohibited and, for the first time in history, in the 1920s, the river became the primary source of drinking water for the city, permanently changing the hydrology of the river.

Visvesvaraya’s suggestions for the river bank and flood management, especially the Osman Sagar and Himayat Sagar reservoirs upstream of Hyderabad, would prove efficient in flood prevention in Old Hyderabad for years to come. In recent times, however, the expanded Hyderabad has faced several episodes of urban flooding, laying bare the impact of rapid urbanisation, the encroachment of lakes and drain canals, and the inability of the infrastructure to keep pace with the growth and development. The old systems clearly need to be re-evaluated, beyond Visvesvaraya’s ideas, to address the concerns in the climate change era.

Transformations, then and now

The bridges, gardens, and other public spaces that came up along the river also made Musi an important part of Hyderabad’s urban fabric. These were intrinsic aspects of people’s lives in Hyderabad, closely tied to the ebb and flow of the river. Historical maps show the ancient grid system of the layout in the city that the Qutb Shahis built, the expansion during the Asaf Jahi era, and when compared to the new cartography points to how the city of Hyderabad changed its relationship with the river as it became the bustling IT capital, especially in the last two decades.

In the post-independence decades, the twin cities of Hyderabad and Secunderabad saw an unprecedented surge in the population and economic activity. Industries came to be located in Hyderabad, office headquarters and universities took shape, migration brought people into the city – all of which meant rapid urbanisation. Urban planning, especially planning that included the Musi, fell short.

Photo: Deccan Archive

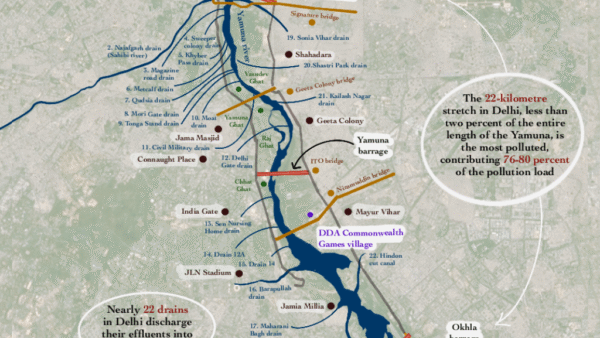

Besides, the rapid growth of the city and resulting change in land use put immense pressure on the city’s natural resources, including on the Musi. There was a dramatic rise in the demand for water, for industrial and domestic use, and the discharge of waste into the river. Both meant a steady, and eventually an alarming deterioration of the water quality of the Musi. The river that had once inspired poetry in the Nawab era was referred to as a Nallah, or open drain.

On the broad historical arc of the river, this meant a drastic shift in its relationship to the city – from a natural asset that nurtured the urban to a receptacle for the burgeoning city’s waste. The discharge of untreated domestic sewage and wastewater has only become worse over the past few years; Hyderabad generates approximately 1,950 million litres per day (MLD) of sewage.

Even as Hyderabad expands with new construction beyond the city limits with new capital and industries in the services sector, the older brick-and-mortar industries stand strong. This means the hazardous cocktail of their effluents discharged into the Musi continues; the contaminants of the bevy of pharmaceutical companies have been particularly singled out, especially in Kukatpally region which has a number of these companies and diagnostic centres.

Recent studies have revealed that the Musi is replete with antibiotics, antidepressants, anti-inflammatory drugs, antifungals, and high doses of caffeine – all detected in concentrations high enough to induce antimicrobial resistance in communities, posing a severe and escalating public health threat. Also, heavy metals such as lead, cadmium, mercury, zinc, chromium, and manganese, originating from various industrial discharges, have been detected in the river’s sediments and water.

Besides the pollution and contamination of the water, the Musi has been beset with continuing encroachments along its banks. A recent survey identified over 10,000 illegal structures; 2,116 of these had been directly built on the riverbed and 7,850 within the buffer or the floodplain zone. These range from slums and informal settlements to unauthorised permanent constructions. Both, despite a wide difference in their purpose and class, have a similar impact on the river’s natural flow, the obstructions to the water, and the pollution levels.

Photo: Deccan Archive

Not unsurprisingly, the degradation of the Musi impacts the people who have lived along the river banks and comprise the most vulnerable sections of the city’s population. In these slums, estimated at nearly 10,000 structures, the poor do not have the benefit of piped water or basic sanitation, forcing them to rely on the polluted river. This increases their exposure to the harmful cocktail of pollutants and damages the water with their untreated waste. Women and children are forced to collect the contaminated water for their households, exposing them to higher risks of disease.

The Musi, undoubtedly, faces a deep ecological distress. But, despite the stench and sorry state, it continues to be an inalienable part of Hyderabad’s social and cultural consciousness. It is remembered in prayer, poetry, ritual, and urban memory as the river that made the city possible. The old constructions along it – from the bridges and temples to its ancient ghats and flood markers – quietly narrate the city’s layered history and relationship with the river. It is not possible to read the history of Hyderabad without seeing its course along the Musi.

From this perspective, the current discussions of river restoration and riverfront redevelopment are not only about its place in the city and the renewal of its rich ecology. While these are significant and critical to the city of Hyderabad, these decisions and actions are also about Hyderabad’s culture and history. The Musi was, and is, Hyderabad’s heritage. Its restoration is, therefore, not only an environmental project but a heritage endeavour. While the Musi must be renewed for its ecology, it must also reconnect the river with the city.

Mohammed Sibghatullah Khan is an architect, researcher, and writer whose work explores the intersections of history, architecture, and urban heritage in Hyderabad and the Deccan region. His research engages with the ways cities evolve over time, the pressures of modern development, and the preservation— and often erasure —of historic urban landscapes. He is the founder of The Deccan Archive, a public history initiative. He conducts walks, lectures, exhibitions. His projects include the documentation of Hyderabad’s mosques, caravanserais, and riverine landscapes, including his current work on the Musi River, tracing its historical transformations, cultural meanings, and the challenges of urban planning and environmental change.

Cover Photo: Muharram ritual in the Musi riverbed in 1898; Photo: Deccan Archive