Stretching across the four states of Gujarat, Rajasthan, Haryana and Delhi, the Aravalli range spans about 700 kilometres[1] across north-western India. Rather than tall peaks rising with might, the Aravalli hill range is a set of ancient folds and landforms with short elevations, in some places barely 300 metres and, at others, rising up to about 900 metres forming rocky ridges, wide valleys, and plateaus. These are, in the Indian geological system, termed as hills.

Elevation of up to 1,000 metres or above is one of the many parameters used to determine that the Aravallis, the Vindhyas, the Satpuras, the Niligirs and several other ranges across India are called hills. Elevations above 1,000 metres, with steep slopes, are termed mountains. Besides elevation, usually taken from the Mean Sea Level, the Indian system classifies landforms based on their origin, slopes, relative relief, and surface forms among other parameters. The parameter of relative relief – the height between the crest and the base – shows around 600 metres for most of the Aravalli range. So, it is a hill range rather than mountains straddling across four states from Gujarat, Rajasthan, Haryana and Delhi.

But defining hill and mountain ranges mostly by their elevation or height ignores their ecological profile and their climatic role. Hills that do not rise high but are covered by scrubs and greens play a vital role in recharging groundwater during the monsoon, preventing desertification, improving air quality in surrounding areas, and supporting livelihoods. Flattening the Aravallis for mining would mean a widespread ecological loss. The Aravalli range along with their rivers and streams are north-western India’s ecological defence.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Redefinition to facilitate more mining?

The Union government’s new definition unifying it across the four states, accepted by the Supreme Court on November 20 and held in abeyance on December 29 after an uproar, classified only those landforms as Aravalli hills which rise at least 100 metres above the surrounding terrain (instead of the standard Mean Sea Level) and two or more such hills within 500 metres of each other, along with the land between them, as part of the Aravalli range. The redefinition was mostly acceptance of Rajasthan’s definition which has the maximum of districts that the Aravallis cover – about 20.

The redefinition was problematic because it left more than 50 percent of the Aravalli range open to potential mining. “Using Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM), Down To Earth applied the definition over 31,414 square kilometres… found that about 49 percent (15,589 square kilometres) would be exposed once the (new) definition is applied and 15,825 square kilometres area would remain under protection. The major chunk of the land area under threat would be in Rajasthan, including the hill station of Mount Abu,” stated the report.[2]

According to India’s Environment Minister Bhupender Yadav, the redefinition would leave open only 0.19 percent of the hills to mining – something that no one believed. Ironically, the government had started the exercise ostensibly to halt the “rampant illegal mining” mostly under the previous Congress party government in Rajasthan which allowed “700 of the 1,008 mines to be set up,” according to his statement.[3] The more the government justified the 100-metre-as-hill, the more it tied itself in knots. “The criterion of ‘100 metres above local relief’ for regulating mining in the Aravalli region as had been in force in Rajasthan since January 2006,” its statement explained.[4] Only days later, the SC held its own order in abeyance.

Mining, infrastructure, city-making at the cost of hills

The mining in the Aravalli ranges has indisputably changed the façade. Nearly half of all illegal mining instances as well as FIRs registered for illegal mining and associated activities (40,175 of 71,332 instances and 4,181 of 7,173 FIRs) in Rajasthan in the past seven years have been filed in the Aravalli districts alone, according to this report in The Indian Express.[5] In some areas, persistent mining from all sides of a hill left behind columns of hills like relics. The Supreme Court’s Central Empowered Committee observed in 2019 that 25 percent of Rajasthan’s Aravallis had been lost to illegal mining and stone crushing.[6]

Just not the hills, vast forest covers in Chhattisgarh and Great Nicobar face mining and urbanisation threats. One of the largest contiguous stretches in central India, Hasdeo Arand forest in Chhattisgarh spans 1,70,000 hectares and has 22 coal blocks underneath. Over 3,68,000 trees “will be affected” by the coal mining project.[7] The villagers’ plea against mining was turned down by the Chhattisgarh High Court last year.[8] The Rs 92,000-crore infrastructure project in the Great Nicobar Island will likely wipe out over a million trees and spell doom for biodiversity.[9]

Other hill and mountain ranges across India have felt and continue to feel the pressure of ‘development’ and urbanisation. Landslides and their aftermath, from Uttarkashi to Wayanad, wreak havoc every year as hollowed-out hills cannot withstand the climate change-related intense weather events. India accounted for the largest percentage – 28 percent – of fatal non-seismic landslides from 2004 to 2016 triggered by construction in hills.[10] The hills are seen as fair game in the march of urbanisation, there to be cut down for mining or unregulated construction, including government projects[11] [12] with their riverbeds and streams showing all kinds of encroachments.

Here’s a look at some of them:

# The Vindhyas

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The Vindhya range has long stood between India’s northern Indo-Gangetic plain and the southern Deccan Plateau, virtually dividing the country’s landmass into halves. It’s also where rivers like the Kali Sindh, Parbati, Betwa, Ken and Son rise housing rich biodiversity.[13] The Vindhyas run in the west-east direction from Gujarat to Bihar, over at least 1,200 kilometres, with an average elevation between 300 and 650 metres.

Illegal mining has been rampant here too. A 2017 report of the Centre for Social Forestry and Eco-Rehabilitation submitted to the NITI Aayog is eloquent on its impact on the local population and place[14]: “Major population was wage-labourers and agriculture as a source of occupation had lost its significance because of land acquisition mainly for mining…The mining is the major source of revenue for Government…Majority of the respondents accepted the negative impact of mining on adjoining forest, agriculture and major cause of pollution. Sonbhadra region had been declared as Critically Polluted Area (CPA) by CPCB in the year 2010… it was found that mining also had a direct negative impact on health mainly due to air, water and noise pollution.”

# The Satpuras

Photo: Siddharth Agarwal/ Wikimedia Commons

The Satpura or ‘Seven-Fold’ hills are among the cradles of India’s wildlife with tiger reserves and protected parks. But where wildlife and biodiversity flourish, minerals abound too which means mining is rampant. The UNESCO states that the Satpura Tiger Reserve “has many rare and endemic plants, especially bryophytes and pteridophytes like Psilotum, Cythea, Osmunda, Lycopodium, Lygodium.” The Satpuras are referred to, in geological circles, as the bridge for the spread of flora and fauna between the mighty Himalayan ranges and the Western Ghats.

In Betul in southern Madhya Pradesh, the Satpuras show the impact of years of mining. “Exacerbated by mining, there is now limited water availability…While the villages benefitted from the infrastructure built by the industry, particularly roads, the township provided a ready market for their produce. The upstream community however suffered from fly ash and coal dust that destroyed the produce and the productivity, depleted ground water aquifers, polluted streams, cracks and subsidence on landscapes. Besides the environmental and health impact of mining, it severely impacted the lives and livelihood of the indigenous community (the Gonds). Closure of mines brought about a complex situation,” stated this in-depth report from TERI in 2021.[15]

Sejal Worah, a conservationist and programme director with WWF India, in this analysis in Mongabay,[16] said there was a “high degree of overlap between coal and mineral deposits and tiger habitats and corridors, particularly in central and northeast India.” The union government report of 2018 pointed to overlaps in the Pench-Satpura tiger corridor where “… a part passes through the coal belt and is under intense pressure from mining infrastructure in the form of roads and railway lines that connect the coal-bearing region with industries.”

A research study[17] found that “the Satpura-Pench Corridor facilitates functional connectivity for tigers and is home to several threatened species, including leopards (Panthera pardus) and four-horned antelope (Tetracerus quadricornis). However, expansion of linear infrastructure and habitat degradation pose an imminent threat to the forest and wildlife within the corridor.”

# The Western Ghats

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The Western Ghats or the Sahyadris merge rugged terrain and undulations with some of the world’s most biodiversity-rich zones, hold the history and legends of the rise and fall of kingdoms, function as a critical carbon sink, and more. The range is one of the world’s recognised 12 mega bio-diversity regions and a UNESCO-tagged living heritage. From the south of Tapi River in Gujarat to the Kanyakumari, the Western Ghats straddle along six states – Gujarat, Maharashtra, Goa, Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu – across approximately 1,600 kilometres with elevations ranging from 300 feet to beyond 2,700 feet at places. The range practically presides over the ecology of peninsular India.

Mining, quarrying and related activities have long posed a threat here and, in some pockets, believed to have triggered landslides. “Runoff from mining has heavy toxic chemical constituents…the Bhadra River in Karnataka has high levels of iron concentration due to the old mining site in Kudremukh, which makes it unfit for drinking as well as irrigation purposes… Bauxite mining in the upper catchment areas of rivers in southern Maharashtra has also been found to have caused the degradation of both groundwater as well as surface water. Along the same fault line, over 300 mining leases granted in Goa are located close to water bodies, most of them are in close proximity to Mandovi and Zuari rivers and their estuaries, which have approximately 90 percent of Goa’s mineral ore being transported through them,” explained this paper citing various local studies.[18]

The Karnataka government acknowledged it too. “The environmental consequences of illegal mining in Karnataka’s Western Ghats have been catastrophic. Between 2010-2024, 4,228.81 acres of forest land were diverted for mining across four districts, with Ballari bearing the brunt at 3,338.13 acres or 80 percent of the total forest loss. This represents twice the extent of forest destruction compared to the illegal mining period, indicating that even ‘legal’ mining operations have intensified environmental damage,” pointed out Karnataka’s Western Ghats Conservation Taskforce Committee.[19]

Kerala, which has suffered devastating landslides in recent years, showed another trend. After the state banned river sand mining in 2016, stone quarries for ‘manufactured sand’ expanded near the protected areas of the Western Ghats causing the loss of biodiversity habitat and wildlife, according to this study which called for “more holistic and integrated approaches to formulating environmental policies and regulations.”[20]

# The Eastern Ghats

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The Eastern Ghats is a discontinuous range spanning Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Tamil Nadu, and Karnataka, running almost parallel to the Bay of Bengal. Home to some of India’s most ancient tribal communities and bewildering biodiversity, the range is also mineral-rich. More than 2,600 plant species have been found here including 454 endemic species. Much of the bauxite resources are found in the Eastern Ghats branching across Odisha and Andhra Pradesh. As per the Indian Minerals Yearbook 2021, Odisha accounts for 41 percent of the bauxite resources in the country, followed by Chhattisgarh and Andhra Pradesh.[21]

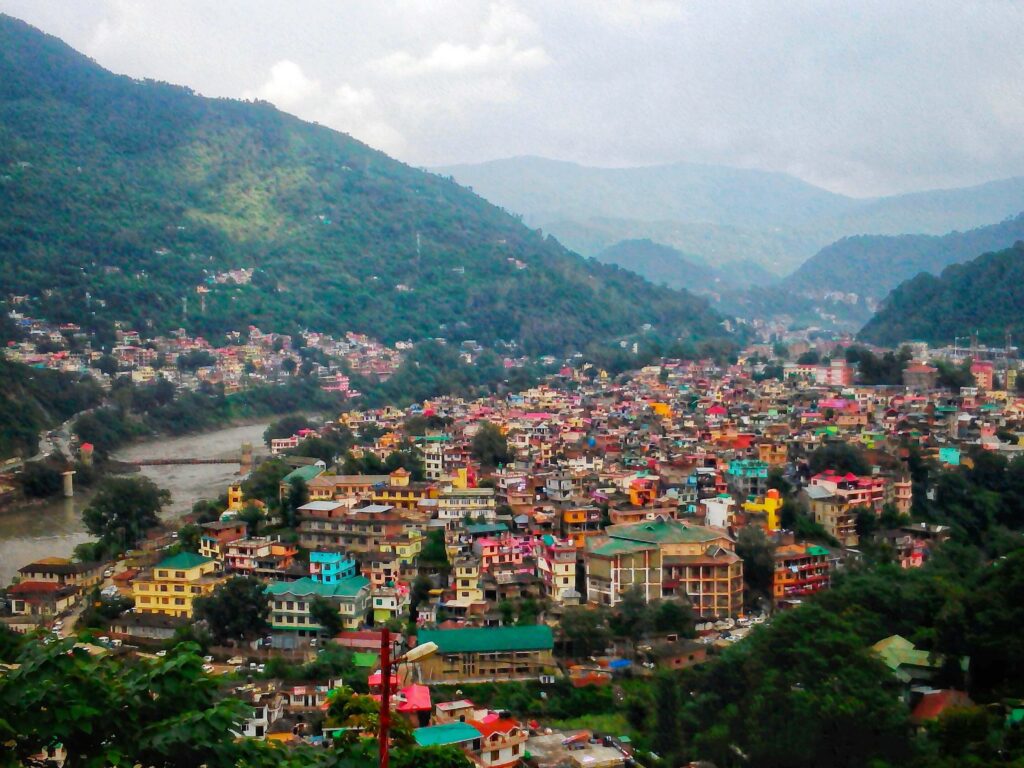

#The Indian Himalayan Range

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Amongst the most studied mountain ranges in the world, the Indian Himalayan Range straddles 12 states and touches a staggering 50 million people in different ways. “The Himalayan region, highly sensitive to climate change, has shown significant impacts on the environment and human communities,” noted a recent paper.[22] From Leh and Kashmir to Uttarakhand, the Himalayas have come under stress from rapid urbanisation and intensified effects of climate change.

In Shimla, for instance, over-construction on the hill slopes to accommodate the increase in tourism has endangered the fragile ecosystem. As Tikender Panwar, former deputy mayor and urbanist, said to The Citizen[23], hills and mountains were traditionally not cut with vertical slits but terraced to minimise instability in these geologically vulnerable regions, but in the rush to complete projects, mountains have been vertically cut into, leading to landslides. The Char Dham saga of tunnelling and accidents has been well documented.[24]

Scientific evidence has underscored the risks posed[25] by large-scale infrastructure development and a number of studies have linked increased landslide activity in the region[26] to construction projects and development. A February 2022 letter from the Ministry of Roads Transport and Highways banning the use of dynamite for development projects here asked that authorities “make judicious use of technology particularly in high altitude Himalayan region to minimise the damage to ecology and environment…as far as possible, rock breakers and excavators may be used in these areas for construction of roads.”[27]

In the mountain town of Leh, rapid urbanisation meant nearly 9,400 new buildings constructed between 2003 and 2017 – the same number built in 34 years up to 2003 – and presented social and ecological challenges. “Urban growth in Leh is driven by administrative and infrastructure development, a booming tourism sector, the diffusion of urban lifestyles, and the region’s geopolitical importance. Our findings raise questions on the consequences of such rapid urbanisation on urban and environmental governance, especially with regard to water resources and natural hazards.”[28]

In Uttarakhand, the absence of urban land-use policy has pushed urbanisation from the geologically-stable mid-slopes and ridges to the environmentally-sensitive higher elevations. Important towns such as Joshimath, Almora, Nainital, Mussoorie, Rishikesh, Dehradun, Uttarkashi, Tehri, Srinagar, Bageshwar, Munsiari, Gopeshwar, Gangotri, Badrinath, and Kedarnath are located either along major tectonic junctures or in their proximity.[29] As urbanisation densifies, the ecologically unsound development makes the region increasingly vulnerable to extreme weather events.

Every study and scientific report has called for a stop to the deforestation in the Indian Himalayan Range besides regulated construction with minimum or no damage to ecology, a ban on cutting and blasting of hills, not using heavy machinery, and regulation of tourism and construction activities.