1. Boiling Point: India’s Amazon India’s Heat Crisis[1]

In 2024, India recorded one of its most severe heatwaves with temperatures crossing 50 degrees Celsius. During this harsh summer, Amazon workers in India were one of the worst[2] affected – they fainted on the job as they lacked cooling infrastructure and pressure to maintain productivity despite unsafe temperatures.

UNI Global Union launched an online survey of Amazon warehouse and delivery workers, with 474 responses coming from India. The findings suggest that the crisis is far from over: Extreme heat continues to endanger lives, protections remain patchy or absent, and productivity is still prioritised over health. The report summarises key survey findings and outlines recommendations to improve health and safety for Amazon workers facing extreme heat. While Amazon often cited compliance with local safety regulations, these compliance measures proved inadequate in environments pushed beyond standard design limits by record-setting temperatures. Workers described the experience as “suffocating,” with health severely compromised in pursuit of tight performance targets.

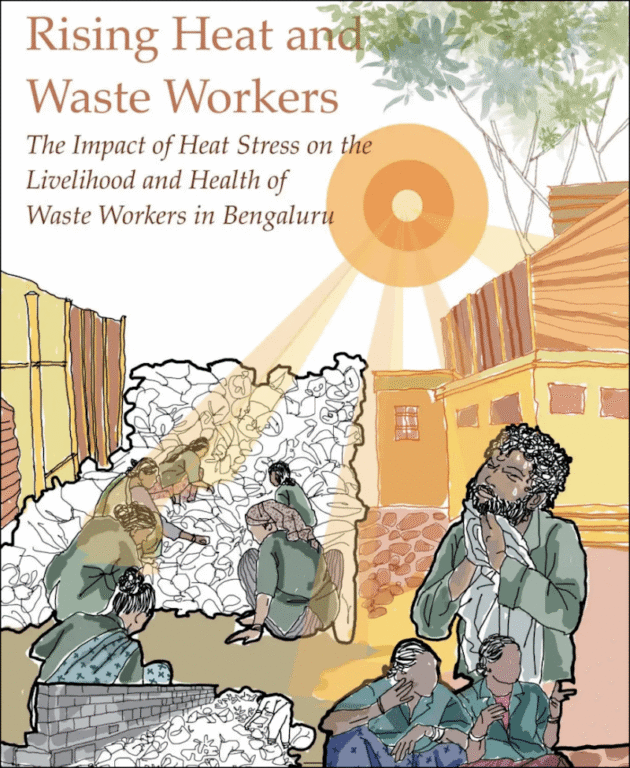

2. Rising Heat and Waste Workers: The Impact of Heat Stress on the Livelihood and Health of Waste Workers of Bengaluru[3]

The study, Rising Heat and Waste Workers, by Hasiru Dala and HeatWatch reveals how rising temperatures in Bengaluru are severely affecting waste workers in terms of heat exposure and vulnerability, income and productivity losses and health challenges.

Over 70 percent workers reported experiencing heat muscle cramps while more than 60 percent workers reported experiencing heat exhaustion along with other symptoms like headaches, dizziness, burning eyes, dehydration, skin rashes and from kidney stones and heat strokes in severe cases. The study also pointed at the lack of amenities at workplaces. Nearly half of Dry Waste Collection Centres (DWCCs) workers lack water, toilets and power supply. Even shade and rest infrastructure are missing. Coping strategies are informal, minimal and self-funded, including taking shade under trees, or buying energy drinks.

The existing Heat Action Plans at the city and state level (BCAP, Karnataka HAP) recognise heat risk but lack targeted, enforceable, and budgeted measures for informal workers. Climate and disaster plans underplay occupational risks faced by outdoor workers like waste pickers. Data on worker categories, heat exposure, and health outcomes is not disaggregated, making targeted action difficult.

3. Hydrological Dynamics in Giant Tropical Rivers: A case study of the Ganga River[4]

This study by IIT Roorkee, published in June this year, examines the summer flow of the Ganga and finds that groundwater, rather than glacial melt, is the primary source sustaining the river in the plains during this period. Using two decades of in situ data, the study shows that groundwater levels across much of the central Ganga Plain have remained stable, which indicates that declining summer flows are not the result of groundwater depletion.

The research analyses river flow across the Ganga’s course, with particular attention to the middle plains, a roughly 1,200-kilometre stretch that is critical for agriculture and industry. In this segment, evaporative losses account for nearly 58 percent of the river’s initial volume, while groundwater discharge contributes to a significant increase in flow, which adds about 120 percent to the river’s volume at the start of the stretch. The findings point to increased human activity, rather than reduced groundwater reserves as a key factor behind diminishing summer flows. Following the publication of the study, the National Green Tribunal took suo motu cognisance[5] of its findings.

4. World Inequality Report 2026[6]

The World Inequality Report 2026, the third in the series, brings together research by over 200 scholars to examine how inequality is shaping economies, societies and democracies today. Moving beyond income and wealth alone, the report looks at how inequality now cuts across climate responsibility, gender, access to education and health, global finance, and territorial divides within countries.

For India, the findings underline how deeply entrenched these dives remain. The top 1 percent of the population holds about 40 percent of the country’s wealth, while the richest 10 percent control about 65 percent. In terms of income, the top 10 percent receive nearly 58 percent of national income, compared to just 15 percent for the bottom 50 percent. These gaps have shown little change between 2014 and 2024. Average annual income in India stands at about 6,200 Euros per person on a purchasing power parity basis, while average wealth is roughly 28,000 Euros. Gender inequality remains stark, with female labour force participation at just 15.7 percent showing no improvement over the past decade.

Globally, the report shows that wealth concentration has reached extreme levels. The richest 0.001 percent, fewer than 60,000 people, own three times more wealth than the bottom half of the world’s population combined.

5. Surviving Heat on the Streets: An Assessment of the Psychosocial Impacts of Extreme Heat on Homeless Persons – HLRN and MHI[7]

This report examines homelessness in India through the lens of rights, public health and climate stress. It situates the rise in homelessness within urban expansion, unaffordable housing markets, evictions, and the lasting effects of the pandemic, and notes the gap between constitutional right to housing and fragmented policy responses on the ground. Focusing on Delhi, the study documents how extreme heat intensifies social exclusion and harms mental well-being among people without shelter. It draws on fieldwork conducted in 2025, and centres lived experiences to show how climate stress, lack of housing and mental health are deeply intertwined.

6. Think India Think Retail – Venture Capital Unlocking Potential 2025[8]

A recent report by Knight Frank India points to a growing number of underperforming shopping centres across Indian cities. Nearly one fifth of the 365 malls spread across 32 cities have either become ghost malls or slipped into near abandonment. These are malls where more than half the retail space lies vacant, which signals a declining footfall and relevance.

The report defines ghost malls as shopping centres that have been operational for over three years and have vacancy levels that exceed 40 percent of their total leasable area. By this measure, 74 malls fall into the ghost mall category, together accounting for around 15.5 million square feet of unused retail space across the country.

Titled Think India Think Retail – Value Capture: Unlocking Potential, the report defines ghost malls as shopping centres that have been operational for over three years and have vacancy levels exceeding 40 percent of their total leasable area. By this measure, 74 malls fall into the ghost mall category, together accounting for around 15.5 million square feet of unused retail space across the country.

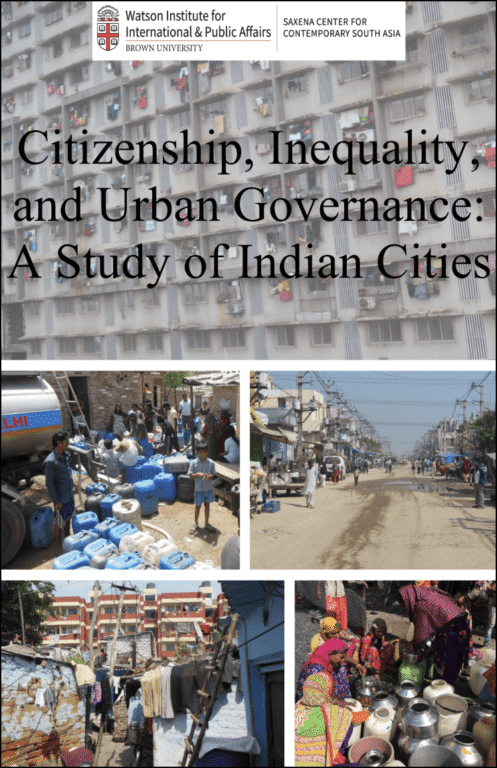

7. Citizenship, Inequality, and Urban Governance: A Study of Indian Cities[9]

A recent study on urban India underlines a familiar but often overlooked reality. While citizenship may be equal in law, it is experienced very differently across the city. This study, a collaboration between researchers in India and Brown University, surveyed over 31,000 households across 14 cities of different sizes to examine how people engage with the state and with each other.

The findings show that access to public services and political participation continues to be shaped by class, caste and religion, with class emerging as the strongest determinant of everyday urban life. The study looks at how residents organise, vote and secure basic services such as water and sanitation. It frames this through the idea of “effective citizenship”, defined by the ability to participate in public life and to claim public goods.

8. COP30 Special Report on Health and Climate Change[10]

Released as part of COP30, this Special Report accompanies the launch of the Belém Health Action Plan. It centres equity and climate justice, and examines how evidence and implementation come together in building climate resilient and low carbon health systems. Structure around health information systems, infrastructure and workforce capacity and innovation and research, the report draws on global case studies to highlight practical interventions already in use. Guided by an international group of public health experts, with leadership from the WHO and Brazil’s Ministry of Health, it also reflects on the limits of adaptation and the urgency of coordinated global action.