When we ask the question, why our cities look the way they do, we assume that cities are meant to hold a visual appeal or a visual idea or thesis. How should cities such as Mumbai or Delhi look? Why do we ask such determinist questions? Our history of planning has also invested in the idea of ‘shaping cities’ not only for a use-value but for viewing value. Why is a ‘good looking’ city so important? Why do we not accept or appreciate chaos or cities that do not have the visual appeal we prefer, we culturally appreciate from particular socio-economic stand-points?

The look of cities, we should appreciate, is a cultural idea. This cultural idea is contextual, located in particular time-space continuums, not in any universal or regional identities such as nations or civilisations. Cities by nature are two things: firstly, they are the distillation of an epoch and its sets of network flows – economic, material worlds, and people; secondly, cities are dynamic and kinetic (in the sense of Rahul Mehrotra’s Kinetic Cities).[1] To design cities is to acknowledge that the material elements and ideas which define a city are harnessed and directed towards a human imagination of life and living.

Cities are the crucible of life, also sites of transaction and exchange. Hence, it is only automatic or natural that a city will grow in promotion of forms of transacting and the speed to participate in this transacting network flows of material and labour, rather than insist that the right to live should translate into the shape and form of our cities. Our misunderstandings of cities results in the utter shabbiness of cities, which we even eroticise at times. And our over-confidence in the economic supremacy in shaping cities results in militarisation of styles – hard decoration of buildings to belong somewhere else, in a golden past or a romantic land elsewhere, but surely dreaming to be anywhere else than where they sit on ground.

We entered the 20th century asking for the grand city of boulevards and view corridors and sight lines, marked by urban monuments and gateways, arcades, trees and parks set to a geometry. We imagined a post-industrial civic world that borrowed from the imperial and mercantile powers an aspiration for living it out in the city. The emerging civic class in the 19th to 20th centuries brought the grand geometry of imperial worlds and mercantile splendour to the everyday arcade and cruising pathways. The city created trophies it could enjoy even if it could not fully live in the glamour of it. We have often enjoyed the look of cities these trophies hold – the Arc de Triomphe and Champs Élysées –and these trophies shifted to the high representation of material exchange and transaction in Times Square as the 20th century glided down in time.

The civil city

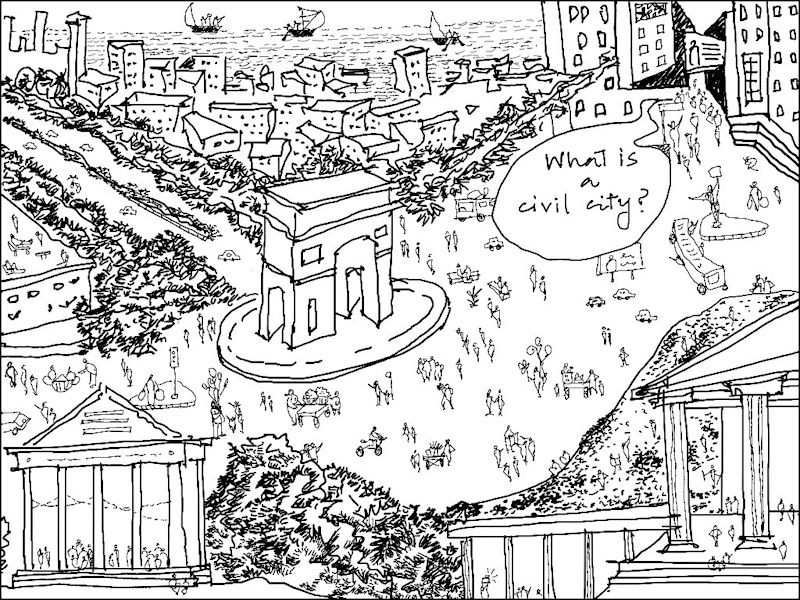

From the histories of diseases to revolutions, the labyrinthine city we have now come to call the ‘inner city’ has been detested and unliked as the unkept, haphazard, squalor that festered germs and anti-social elements not worthy of the civil city. But what is a civil city? How can we keep the city – humane and civil, can we have commissions that maintain a sense of humanity and dignity for the masses that live and work here, through the ways in which we decide how our built volumes and masses, spaces and alleys shape up?

Rabindranath Tagore, in his important essay, “The Creative Ideal”[2] says: “Society suffers from a profound feeling of unhappiness, not so much when it is in material poverty as when its members are deprived of a larger part of their humanity. This unhappiness goes on smouldering in the subconscious mind of the community till its life is reduced to ashes or a sudden combustion is produced. The repressed personality of man generates an inflammable moral gas deadly in its explosive force”.

Our universal imagination of the ‘civil city’ has been historically driven by the idea of the Greek Agora, and this intellectual tradition coming from European thought is indeed universal, whether we like it or not. The fact that the world was colonised in the time that we moved to the large people’s city, the cities of masses, is unchangeable; our previous models of cities across the world only indicate the imperial or mercantile models of organising public affairs in what we would call public or civic spaces.

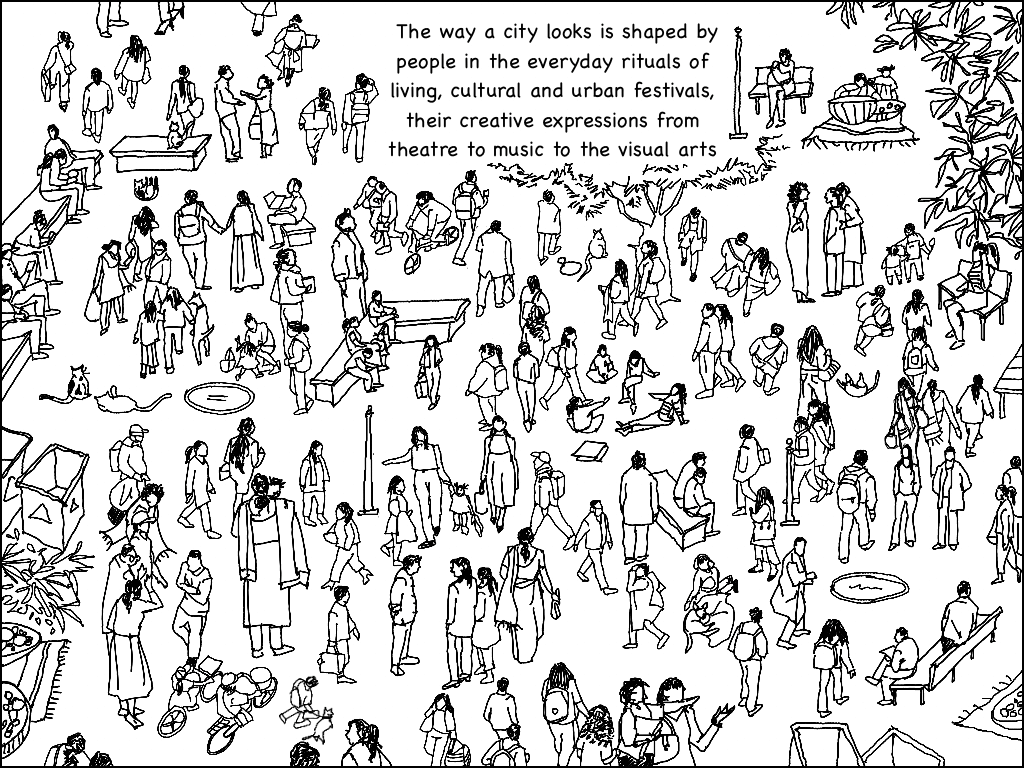

The civic-human is often brought to the city by the public in the form of the ritual procession of cultural and urban festivals or the everyday rituals of living and the cultural life of creative expressions from theatre to music to the visual arts. In which case then, the facades of buildings and roads in between, become the containers of life within which everyday life unfolds, and they survive a memory beyond the everyday living. The aesthetics of a city are embedded in this exchange of theatrics between the facades of our buildings and the unfolding human motions of life either in the routines of the everyday or in the heightened moments of art, rituals, and festivities.

The urban façade, in its design by idea and ideology or by chance, is the outcome of the city’s struggle between the forces that manipulate its transacting nature as well as the profits to be squeezed from it and the struggle of people to find ways of living life, between its full potential of human imagination and health as well as its wrestle to survive. The fact is that we accept the forces of transaction to make us believe that the city is only about transactions and not about the social nature of human civilisation and creative being, that our cities bear the looks of just surviving or heavily carry the aspirations of being on the top of the material transaction pyramid.

Liveable city, inner city

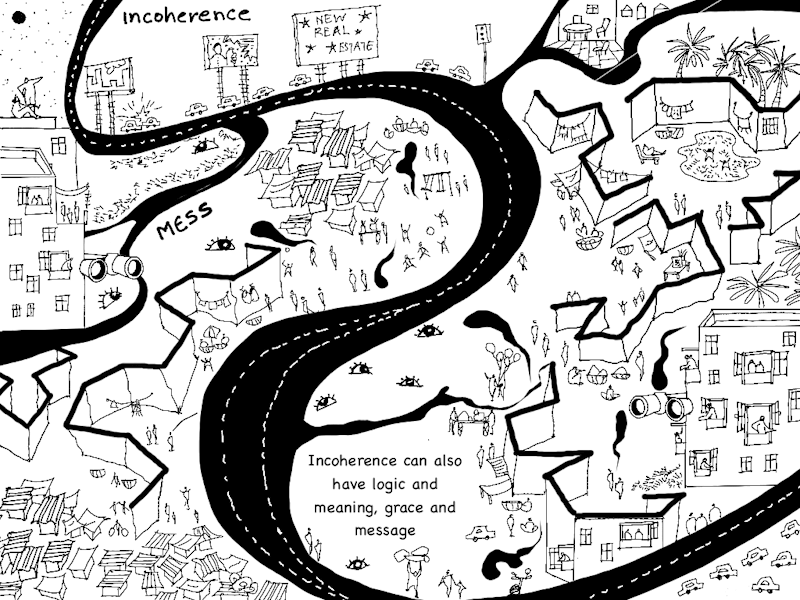

The liveable city is not the one we should ask for or work for, because if you think the liveable city is the epitome, or the jugaad city is to be celebrated, you will get a city that is surviving to live through the mess. What we have to ask for is the city’s right to be designed for collective living and growth, one that is kinetic-creative; here the creative is not the industry of design but one of dynamic creative thinking as an everyday act of being, where the everyday brews a culture of thought-building.

The urban aesthetic resides not only on the facades and boulevards of our urban environments, but it is in the insides of our cities – which is why we have been looking at the inner city again and again. However, the inner city has now become a stereotype and exotica of its own self, locked up in heritage walks and conservation precincts rather than the kinetic ecologies they have grown through. The city of boulevards has killed the neighbourhood of inner cities; neighbourhoods that survive and build an experience are the ones where boulevards and alleys can coexist as continuous ecologies rather than binaries.

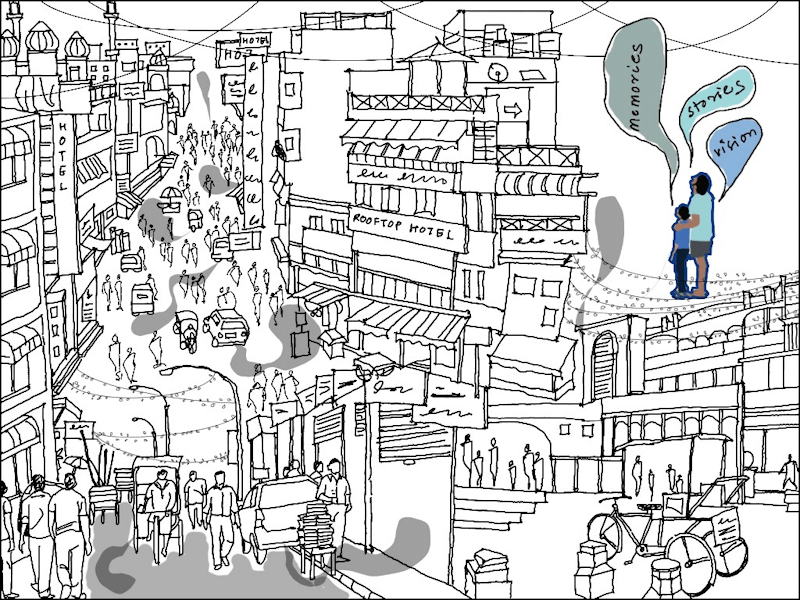

We forget that we never ‘view’ cities…we love seeing a city down a high rise, or from the camera in the flying drone, because we never really see the city – what we always see is the city in its million parts. A city is best seen through our persistence of vision and memory, where the moving resident and occupant collects the city as they move through its parts, and the ‘man of the crowd’ (borrowing from a story title by Edgar Allen Poe)[3] can see as an individual in the crowd the city walls and spaces unfolding not just physically but as creative tectonics of living.

Aesthetics: more than a beautiful view

A city’s aesthetic experience lies in its spatio-visual kinesis, and aesthetics is a creative state of being, so if a city is beautiful in a one-point perspective where the viewer is static and in the state of reception as a static entity, it is no beautiful city, it is only a pretty picture in the messy city. Or maybe it allows us to believe that there are only a few positions – geographically or economically, or in terms of importance – that beauty in a city may not be the state of its being.

A beautiful city unfolds in its openness (with reference to Richard Sennett’s Open City)[4] mixing experiences and many eyes on the street, letting them all see each other in their variety and differences. A street has unfolding facades rather than facades of a ‘mass ornament’ (with reference to Sigfried Kracauer) behaving like the orchestrated trapeze group of individuals and stage of ‘tiller girls’ – where we enjoy the mass formations but miss the individuals.

The urban is not only what we see in the public arena and sphere because we live in between the public and the private realms, and many spaces that belong to both realms. From the nondescript alley to the cinema houses and bars, to public newspaper rooms and street corners with tea-shops, the city is shaping and unfolding its inhabitants through these multiple spatio-visual experiences – and hence the aesthetic understanding of the city is an accumulation of these many overlapping sights and sites.

Once we select only a few parts of the city to impress an aesthetic text, and imagine that mess or incoherence has to be eroticised, we are ourselves making a mess of the city we are not just living in but shaping human and civilisational lives in. That incoherence can also have logic and meaning, grace and message is important to acknowledge, without being blinded by its erotica and making it an exotic trophy of sorts. Maybe this incoherence is our city’s way of telling us something – either our missing capacities to see an emerging language of everyday-ness or lazy governance or disenfranchisement of lives, or disregard for the variety and richness of human life that shapes up in a city.

Think of the vast housing stock that makes the bulk of our cities. We often think of house and housing, but rarely do we allow for the delicate idea of home to drive our design of apartment buildings and other typologies of living spaces. Housing is rendered in two transactional forms – either as a responsibility to provide shelter and, hence, you stack walls after walls and roof after roof and fill people somewhere in between; or the high value aspiration to be traded for financial gains in which case the building becomes a trophy object again within which people will be packed. But in neither case the home engages with the city; we rather divorce home from the city or ask home to be on the streets otherwise, most often disgracefully.

So, our cities exhibit a collage of trophies dancing in the air or people detest the look of our urban facades and walls that are just about sheltering human individuals within while the city outside is continuously stripping you of hope and dignity to live a creative life. The city will only be beautiful if it has respect for human dignity and believes in a civilisational quest for human creative capacities, to shape their worlds with ideas and spaces that are constantly growing, changing, adapting and contributing to this creative unfolding – a kinetic-creative sense of the urban is the aesthetic of a good city that lives beyond surviving or jugaad, and thinks of human life beyond simply material transactions. The ability to think of life as a creative process that a city nurtures will bring us a city of aesthetic prosperity.

Kaiwan Mehta is a theorist and critic in the fields of visual culture, architecture, and city studies. Mehta has studied Architecture, Literature, Indian Aesthetics and Cultural Studies. In 2017, he completed his doctoral studies at the Centre for the Study of Culture and Society, Bengaluru, under the aegis of Manipal University. In April 2022 he was appointed the Dean at Balwant Sheth School of Architecture, at SVKM’s NMIMS University. He was recently elected to the coveted International Committee of Architectural Critics (CICA). He has authored Alice in Bhuleshwar: Navigating a Mumbai Neighbourhood and The Architecture of I M Kadri.

Illustrations: Nikeita Saraf