What is your idea of the order of nature-cosmos, the interconnectedness of life, that you have spoken and written about. How does this reflect or not in the aesthetics of a city?

I think the aesthetics of a city is a byproduct of many concerns and many processes. It is not an afterthought; it cannot be compartmentalised. It is currently being seen as a kind of ‘beautification’. These are false notions, they are also completely misleading because they trigger uglyfication, not beautification. Also, aesthetics has to do with all communities, all strata of society, and in perceiving and making common spaces as the ground for whatever is imagined as the beauty of the city. This, we see and can learn from even traditional cities.

Is there a common ground or consent of what makes urban aesthetics?

Not at the moment. If you go to any old city, you will find that their spaces are creative negotiations. Communities and individuals come together and realise the common ground for their respective needs. We find this in old Bombay when, in the early 19th century, some privileged visionary individuals created places for their communities, which are now cherished as historic places and spaces of Mumbai reflecting its character and heritage. This does not happen now; designers, bureaucrats, and politicians are working with different perceptions of the city. We have to be aware of manifold visual expressions of different communities – wall paintings, murals, crafts –all of which form the content of aesthetics in cities.

Cities become beautiful not only because of the quality of its architecture but also how they intermingle with nature, landscape, and other forms of life as a whole. We work in silos. This is the problem. I think, we architects and urban designers, have not been effective in raising the consciousness of our citizens to this concern. There’s a lot of advanced engineering seen in flyovers, underpasses, and skyscrapers but they don’t seem to regard the environment, the context, the history, the sociology as their inheritance. You find fantastic resolutions in engineering and technological ventures, but they are at completely different tangents, sociologically and environmentally. I believe that engineers and architects have taken different routes; earlier, we belonged to one consciousness.

How can we say something is ugly and something is aesthetically good in cities when this is dependent on different communities, cultures, decision makers, businessmen? When a particular architect creates something, some may say it’s ugly but it gets appreciation from others.

The city is for all, not for a particular community or any one stratum – this is a major factor to be appreciated. The other is that we have to remember that the term aesthetics came into architecture from linguistics, poetry, and philosophy. It was not a term used by architects. The Greeks thought ethics, philosophy, and technique, or the philosophy behind each of them, led to creating beauty. We find that it happens when we work together and resolve questions of spaces.

Today’s definitions are convenient for manufacturers, marketing people, and business stakeholders. For instance, there’s so much talk about ‘sustainability’ but we are making buildings clad in glass. Primarily, such notions come from manufacturers and people with profit motive exploiting land as the resource. Take the example of the textile mills area in Mumbai. The Charles Correa Committee proposed[1] that one-third each was to be used by developers, for mill workers’ housing, and for public spaces. But this was completely undermined in the implementation. This shows the paradox between what can be done and what it is actually done, when personal interests are put ahead of the city’s. A paradigm shift is required in the perception of what the city means to all of us.

One of the themes you have been talking about is the interconnectedness of life. Our cities rarely show this in ecology or people’s relationships. How should interconnectedness reflect in a city’s aesthetics?

Let us take the principle with which our cities are being planned today, the measure and only question is people’s commutes. Cities are not planned for people, pedestrians, but for vehicles. In Mumbai, the metro car station in Aarey,[2] for example, was planned by chopping thousands of trees. Was it possible to avoid this, is the question. The approach seems to be that the trees can be planted anywhere but people have to move. Every place has its own natural characteristics, topography, vegetation, rivers, lakes, ocean, hills, and wild life whose habitat it is. Can we only prioritise human needs for habitation, recreation, business and overlook these? Life is interdependent on all these factors. If our consciousness had truly been more inclusive, it would reflect in making our cities beautiful with our ideas of a sustainable life.

Are you saying that skewed development policies and large infrastructure projects that prioritise motorised private transport turn out an ugly aesthetic in cities?

I think even that has the potential to create better intermingling. For instance, in Goa, Charles Correa was trying to resolve a traffic free zone around the Panjim Church.[3] One of the ideas was to create a hop-on hop-off in the central area regulating heavy vehicular traffic and making a wonderful pedestrian plaza. In Mumbai, there are people working to promote public transport. I’m not saying the flyovers and bridges are not required but asking if they can be integrated better, if they can address human habitation without hurting other forms of life, if they cannot be blind to the city’s history. The Navi Mumbai International airport, for instance, has come at the cost of a river[4] that was turned. Was this not avoidable?

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The question about aesthetics is, therefore, how we approach these projects. We just nut-bolt projects here, a star-architect is invited here to do awe-inspiring work. The government, the industry, the business, and the common man, all love the novelty. The problem here is the tendency to worship what comes from outside but we don’t see good integration. Why is that? Pune is now getting all these flyovers which have torn its fabric and created a new aggressive landscape. Is this aesthetic? Of course, cities have to grow but I am asking if the existing fabric can be used more sensitively rather than torn apart.

What has happened is that if an architect is designing a building, the engineer comes and tells you what is to be done. The earlier four-storey building integrated well with the environment and vegetation, but the engineer happily makes it a 50-storey structure because the technology is available. This kind of adventurism or utilitarian greed is tempting all those who see land as something to be exploited for profit alone. This becomes the ground for visualising development and aesthetics.

When profit-driven function over form is prioritised, whose responsibility would it be to speak out? Would it not fall on architects or urban designers?

It’s everybody’s responsibility. But architects too have their own agenda. Also, many architects don’t see this as a problem. The architect is on the razor’s edge where you have to make profits and promote yourself, but there are also wider issues. Who is the biggest client of architects? The developers. What is their agenda, what is the developer-politician nexus? For both, to exploit land for profits. This is why, for instance, in the Mumbai mills area, there are now big buildings[5] with 4,000-5,000 square feet apartments, two swimming pools, three banquet halls, and lovely lawns with very low density where old couples live.. This is the paradox. It can be arrested if we are more conscious.

I outlined four relationships – the I:I, I:other, I:nature, and I:whole cosmos. Becoming conscious of these relationships may help in balancing our needs, aspirations and aesthetics; by neglecting, there is imbalance, expression of power, and unsustainable cities. Architects and urban designers can speak up more but they will be effective if they’re involved with communities, not talking for themselves. Star architects do not help although they become a model for the younger generation. Idol worship, idolising stars and technological prowess, have an adverse effect on aesthetics.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

When the Navi Mumbai International airport and Mumbai’s underground metro were inaugurated, everyone from the Prime Minister to the Chief Minister hailed them as magnificent engineering marvels. This sets the trend for our cities. There seem to be two approaches. How do we say one is better than the other?

This question requires us to go into the whole philosophy of aesthetics. If you take visual arts, movies, poems, performing arts, and literature, together they cultivate our sensibilities and shape them. We have lost the focus of these interconnections. The celebrated abstract painter VS Gaitonde was a very senior friend and I knew him closely. In 1986, when I wrote[6] about him, he was only known to painters and some of us, not to the common man. Our consumer society does not gift art works. The consciousness of beauty seems to work in a compartmentalised manner.

Visual ideas come from philosophy, literature, poetry. How many of us read poetry or listen to classical music, or music from other cultures? Exploring other forms of creative expression builds one’s sense of aesthetics, holistically. It was Marshall McLuhan who said ‘the medium is the message’[7] – if the media makes people believe something is beautiful, they buy it. So also, art. For many years, visual aesthetics and arts were not part of interdisciplinary seminars where sociologists, historians, and others discussed aesthetics. In the last 10 years or so, the trend has slightly changed. But the big question is about the media. And what our talented young are learning. This is what is churned out and what dominates the marketplace. .

So young architects and urban designers are embracing what guarantees them success.

I recall the wonderful biography of the Hindustani classical singer Gangubai Hangal where she talks about when she and Pandit Bhimsen Joshi were both learning from their guru Sawai Gandharva. She would come to Kundgol from Hubli and, on her return, young Bhimsen would accompany her back to the station asking what their guru taught her. There’s learning there at so many levels. This is not just training under a guru but getting to the core of the process of the music itself. This is how the sense of aesthetics flowers, from guilds of musicians, from art and craft traditions. In today’s system, the teacher gives software skills to the student to perform, that’s all the professional offices also demand of them.

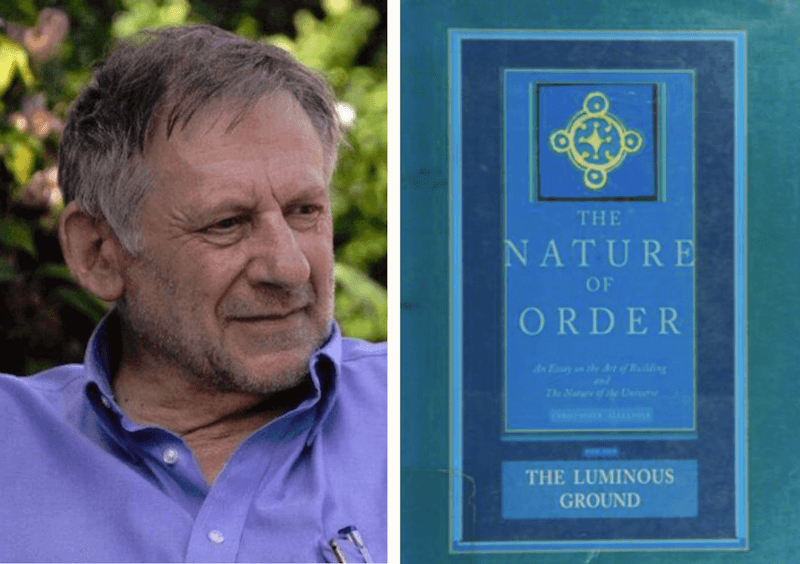

We learn what is good or bad by doing. Indian aesthetics recognises the three layers of gross, subtle and transcendental that an artist needs to be conscious of. We see this in Konark temples where the sculptures by novices are at the back and lowest level, by doing, they become mature craftsmen. I’m also thinking of Christopher Alexander who wrote four volumes about the Nature of Order[8] and his narration of how a father and son in Japan did traditional plaster on walls. The son finished quickly while the master was still at work. There was a difference in the plasters – how these adhered, their finish, and texture, how they appealed to senses. The master’s work reached almost spiritual subtlety. All this is also the philosophy of aesthetics. Japanese minimalism owes to Zen Buddhist philosophy, it reached all aspects of design, and permeated in the culture of that society. There’s a dialogue between the process of making and thinking; they are inseparable. As architects, we must be engaged in both.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The architectural work we see, the kind of styles emerging, is a palette of choices that clients or patrons pick from. Architects are service providers, cut-pasting from what they think will work. What then happens to the aesthetic that emerges?

It’s a complex process. What you mentioned is what is happening; the architect is being used, just employed, by a patron who says ‘I made this building and I had kept an architect’. But there is also a different situation where a person or a community and a team of architects come together to understand a problem – not with a fixed agenda or image – and evolve something wonderful together. In the first case, the architect is a slave. Such patrons dominate the aesthetic as per their fancies. In the latter case, there may be limited good works of architecture but they become important and inspiring landmarks.

In schools of architecture, at least in some, we teach values which can reflect in aesthetics. What are these? I still admire, for instance, Le Corbusier’s Carpenter Center because each time the space looks different, the landscape is running through, it is not an afterthought but a kind of reverence for landscape. We may have differences of opinion on his Chandigarh plan but the fact is that the landscape flows through the city continuously in varying streams. Le Corbusier was unhappy when his idea of 60-storey buildings in Manhattan was misused. I touched upon some of this in my book Dialogues with Indian Master Architects.[9]

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

In cities, individual works of architecture and neighbourhood spaces blended together, like the Khotachiwadi[10] in Mumbai, present us with an aesthetic. There’s a falsification of the concept of density. James Law, who is doing skyscrapers in Mumbai, once told me he was designing a drone to pick up prefab blocks of apartments to build a 100-storey building. The question is does our study of urban densities demand a 100-storey building? So, aesthetics is not only about what technology can do but whether it is integrated well, harmonised. A tower cannot be not sustainable if it’s at the expense of communities or huge energy consumption. Sustainable is our current currency term – the French called it durable – but it was in practice in the 12-13th century Hemadpanti temples of Maharashtra, which could be completely dismantled and erected elsewhere, stone by stone.

You used the phrase ‘action coupled with awareness’. There’s now an awareness of what’s needed, say climate change, an awareness that the built form segregates people from the environment and one another, but what is the action needed to bring this awareness into reality in our cities?

It’s happening in pockets but not everywhere. There’s a whole community of architects, brilliant and talented, and they are disillusioned with the so-called modern architecture, exhausted modern architecture, which continues to be taught. And the isms from the developed worlds are taught here because we are bankrupt in teaching criticism and philosophy. That’s why MN Ashish Ganju and I wrote “The Discovery of Architecture”: A contemporary treatise on ancient values and indigenous reality.

There are many architects working in villages, tribal communities, and cities concerned about the informal sector and the environment. Young architects are working with mud. In Tamil Nadu and Bengaluru, people are conserving water because that’s the need. However, many architects are also completely engineering driven, into technology, and adapting design processes mechanistically. Earlier, we worshipped machines, now we are going to worship AI.

The coming of AI produces new values, new outputs, and has its own dynamics. How can the values and processes in architecture and design be sustained?

There are four value-based points we made into a matrix. Draw a spiral of time and the four points will always be on it. What are they? The relationship of self and society, action coupled with awareness, maintenance as renewal, and regeneration with learning. Architecture and arts will happen in the encounters between these. And in architecture, when action is coupled with awareness, it is like Bhimsen Joshi discussing with Gangubai Hangal how a particular raga was taught to her one way and to him another way, and there was a sense of discovery in the subtle nuances of it for both though neither of them sang the raga the way their guru did. This is an important aspect. We do, we learn from that, and we rediscover. There has to be rediscovery. If I negate this, say my ego is so big that I won’t listen or read or engage, then there’s a problem. That four-point spiral is the journey of rediscovery.

Cover Photo: Delhi’s Lodhi Art District. Credit: Pixahive