October always arrives in Delhi with the intoxicating scent of Saptaparni (Alstonia Scholaris) and Shiuli (Nyctanthes arbor-tristis). From my balcony, their fragrance feels like a gentle promise of cooler days ahead although the monsoon this year overstayed its welcome and softened the usual heat. A friend, who despises Delhi’s summers (who can blame her?), counts down the days to winter. I, on the other hand, feel a sense of dread rising with the chill. By mid-October, the air has turned heavy, my familiar pollution headaches have returned, and the AQI[1] steadily climbs, cutting short my brief trust with autumnal joy.

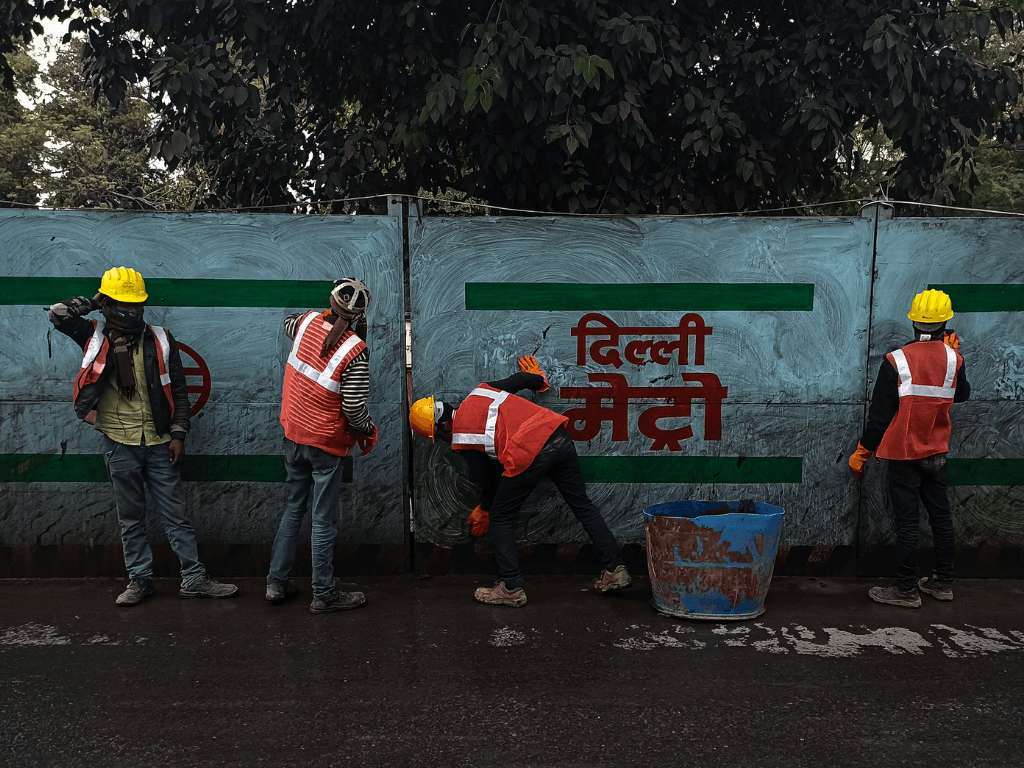

But the heaviest burden of this poisoned air is borne by those who can least afford it. As pollution levels spike, the government’s Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP) kicks in. Construction work stops, choking the livelihoods[2] of daily-wage workers who already live in cycles of debt. Labour unions point out how compensation, despite being ordered by the Supreme Court,[3] is rarely disbursed on time. Workers now dread the pollution season as much as they dread illness.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Yet, cars keep moving through the smog, roads stay jammed, and the restrictions never touch the city’s elite even though vehicles remain one of the biggest sources of Delhi’s air pollution. Earlier this year, the newly elected BJP government touted its decision to ban “end-of-life” vehicles as a pollution-control measure. But experts[4] have called this cosmetic—a policy that targets the visible symbols of decay rather than the structural causes of pollution. Without redesigning traffic flow, improving public transport, or curbing fuel adulteration, such measures do little more than preserve the illusion of environmental action.

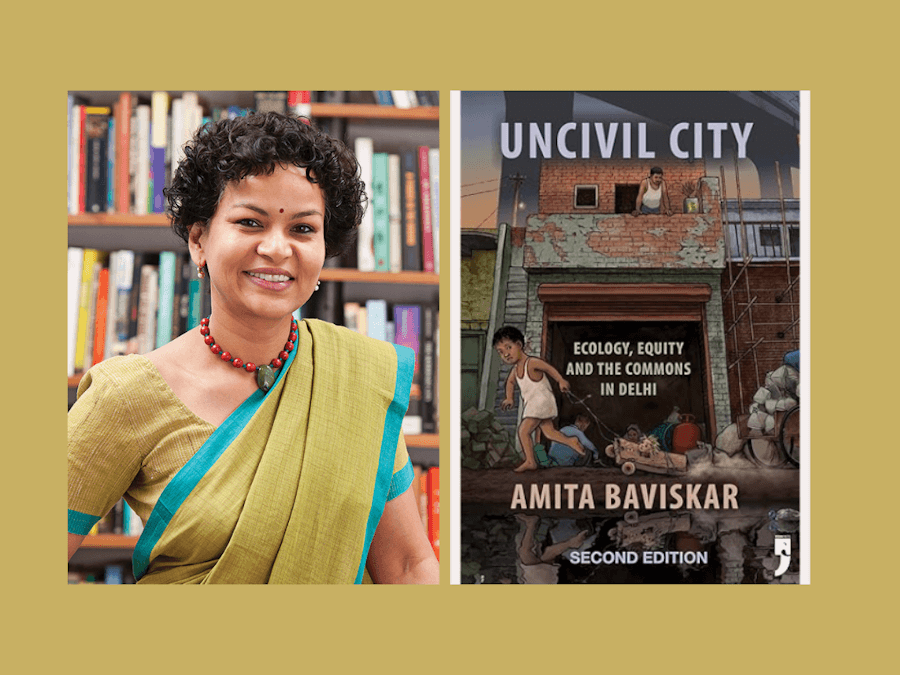

As Delhi lurches from floods to heatwaves to smog, its vision of urban progress coming at the cost of its ecology – and its poorest residents – I picked up Amita Baviskar’s Uncivil City: Ecology, Equity and the Commons in Delhi, to not only make sense of the city’s unfolding environmental crises but also who gets to belong in the city. For decades, the city appeared an unlikely site to worry about ecology or its impact on people. But the book could not be more relevant than in 2025.

Baviskar, the renowned sociologist, currently Professor of Environmental Studies, Sociology and Anthropology at Ashoka University, turns her – and our – gaze to the capital’s air, waste, rivers and people in Uncivil City. In her choice of subjects as much as the intersectionality she focuses on, Baviskar nudges us to ask what it means to live with and against nature in an urban world. For a first-time reader, Uncivil City is an eye-opener, an education; for a repeat reader, a reminder.

Baviskar shows how environmental conflicts are just as charged in the city as they are across rural India but points us to the difference: While rural communities have mobilised collectively against displacement and loss of land, the urban poor in Delhi are scattered and fragmented, often pitted against each other in the daily struggle for survival, and find it far harder to stake a collective claim to space, housing or even clean air, rights that are increasingly monopolised by the elite. Baviskar terms this “bourgeois environmentalism,” an environmental concern driven by the middle and upper classes, where the impulse to clean and beautify the city ends up excluding and inevitably punishing the poor.

The “bourgeois environmentalism” celebrates tidy parks and air purifiers while ignoring the labour and displacement that make such order possible. Baviskar shows how this logic has shaped Delhi’s ecological landscape – from the drive to shut down[5] “polluting” factories that displaced thousands of workers in 1996, or efforts to “reclaim” the Yamuna floodplains for so-called public good. One can add the Supreme Court of India, during the pandemic, ordering the demolition of 48,000 jhuggi-jhopdis on the New Delhi railway tracks in the name of environmental protection.[6]

“Smouldering mountains of our garbage poison the air and ground,” Baviskar writes, “Summer temperatures soar because of the heat island effect caused by glass-concrete-tarmac and waste heat from air-conditioners, generators and vehicles. We can’t handle any of these problems and yet the government wants to build more, crowd more into an already congested city. Is this what we should be constructing: more ecological mayhem?”

Photo: QoC File

As one living in Delhi, I often feel this contradiction. I chose a neighbourhood which doubles as a student hub and its thriving ecosystem of hulchul, and its commons. The weekly Tuesday market, the small parks, the modest dhabas, people casually leaning against parked bikes – these spaces keep it alive and remind me of my years in North Campus. Back then, the ridge, Mirabai Park, and the Arts Faculty lawns were our meeting grounds where friendship and resistance spilled into the open. Baviskar, too, recalls her own university days, growing up as the child of a Delhi University professor and her own fondness for markets that stitched community life together.

“A good market”, she observes, “is one that is useful and fun. Mukherjee Nagar market near where I live is both. Its potholed lanes and dingy buildings contain shops that will make you cotton mattresses and photocopies, repair a pressure cooker or a puncture, make hot jalebis and fresh fruit juice, and do Special Waterproof Bridal Makeup so that you can sob your heart out during bidaai and still stay unsmudged for the camera.”

But these worlds are slowly vanishing. Each new “redevelopment” project replaces these tangled ecosystems with glass-fronted stores and gated markets. As rents soar, small traders are forced out, the neighbourhood chaiwalla bhaiyas and gol gappewalas disappear, and the sense of belonging that Delhi offers to its multitudes thins out.

Importantly, Baviskar treats this loss not as nostalgia but as politics, specifically, the politics of urban planning. The erasure of such commons, she argues, reflects a city built for consumption rather than coexistence, a city that privileges order over life. “Places that, with a careless generosity, welcomed all—different species of living things as well as different classes of people—are now being parcelled out into the custody of the privileged few and placed out-of-bounds for everyone else.”

Who has the right to the city’s environment, its ecology? Certainly not the urban poor. To drive home this point, Baviskar recounts a chilling incident[7] from January 1995 when residents of Ashok Vihar, an affluent Delhi neighbourhood, beat a young man named Dilip, who lived in a jhuggi basti nearby, to death, for defecating in an area they considered ‘their’ park. The park was part of an ongoing feud where to one set of residents it meant their private gardens to stroll, and to another, due to a lack of toilets in their slums, turned to open spaces as a toilet. The tensions led to the deaths of four people amidst a police firing.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Such moral claim over public spaces is visible even today — in gated colonies where Residents’ Welfare Associations (RWAs) erect boom barriers on public roads to control entry and exit. Whose safety do these gates serve, and against whom? Such measures create an illusion of security while sealing off the possibility of a shared urban life. Is this not an insular way of living that cuts off any connection to the city’s public realm?

This exclusionary urban imagination has roots in the city’s planning history. The Delhi Development Authority (DDA), set up in 1957 with the Ford Foundation’s assistance, aimed to create a “model” city – modern, orderly, and hygienic. But as Baviskar notes, this vision ignored the labour that sustains it. The DDA prioritised middle-class housing (High Income Groups, Middle Income Groups, Low Income Groups) over homes for the working poor, for whom no provisions were made. The result: a neatly planned Delhi built atop the parallel growth of its so-called “unplanned” counterpart.

So how do we reimagine the city that has been fractured along such differences? What future awaits Delhi, as smoke fumes envelop the city, a little thicker every year? What stakes do each of us hold? In asking such questions, Baviskar compels us to see and acknowledge that the city’s environmental and ecological crisis is also a moral one. “…this city is a collective endeavour, an ongoing public works project that involves us all. Yet, we deny the interdependencies that make the city possible, forever seeking to undermine the dense fabric of social and ecological relations that gives Delhi its distinctive identity. If the Ridge and the river are destroyed, then so is the air and water and the habitats of other species with whom we share this place. If the republic of the streets is conquered by commerce and cars, we lose something precious that belongs to us all, rich and poor—the chance to recognise and rejoice in our common humanity. The death of Delhi’s commons will be the end of Delhi, and that will be tragic.”

Perhaps the only way to reclaim what is lost is to reimagine how we live with one another and with the city itself. This is where Baviskar turns to the idea of civility – not the bourgeois notion that hinges on the exclusion of the marginalised, but one that is marked by a deeper ethic of care and coexistence. In this idea of civility, people recognise one another as equal citizens, not as intruders.

She writes: “We need forms of city-wide neighbourliness where mutual respect, reciprocity and restraint can bring about radical change by being aligned with democratic principles.” Such ‘neighbourliness’ asks us to move beyond gated lives and selective compassion, towards a city where living together also means caring for the shared spaces, air and the futures that bind us.

Ankita Dhar Karmakar, Multimedia Journalist and Social Media in-charge in Question of Cities, has reported and written at the intersection of gender, cities, and human rights, among other themes. Her work has been featured in several digital publications, national and international. She is the recipient of the 4th South Asia Laadli Media & Advertising Award For Gender Sensitivity and the 14th Laadli Media & Advertising Award For Gender Sensitivity. She holds a Master’s degree in English Literature from Ambedkar University, New Delhi.

Cover Photo: WordPress

Title: Uncivil City: Ecology, Equity and Commons in Delhi

Authors: Amita Baviskar

Publisher: SAGE Publications, Yoda Press

Year published: 220

Pages: 243

Price: Rs 419 (Paperback and Kindle)