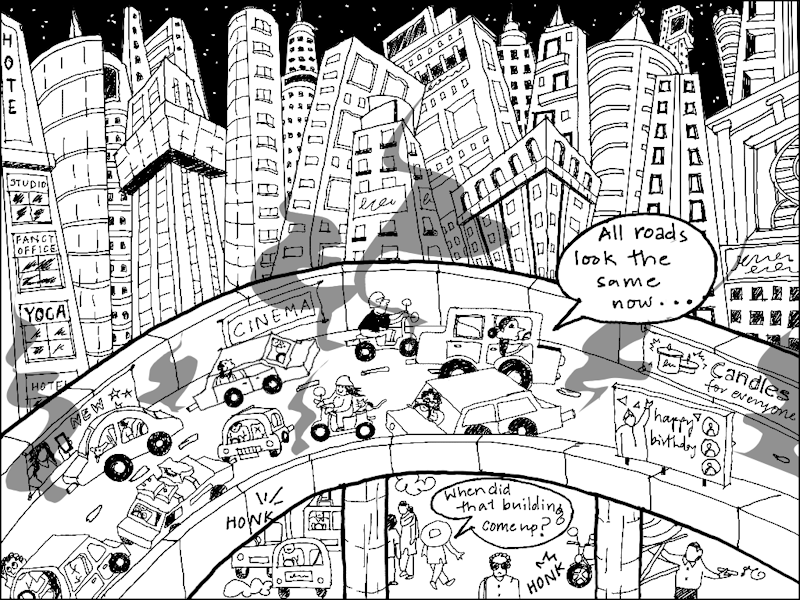

If we take off the lens of the architect and planner, density reveals itself in multiple ways, as my illustration above shows. It is a skyline of sameness stretched over all our cities like a large, manicured canvas. There’s density of buildings as far as the eye can see, there’s density of vehicles on flyovers, and there’s density of people and activities on the street below. To un-see density in its purely technical meaning and see it from the perspective of how it unfolds in our cities, the multifarious impact it has on people including invisibilising them, the damage it continues to wreak on the natural areas in cities is another story altogether. Or a storyboard, as I chart it here.

It could be a flyover in Mumbai, Gurgaon, Bengaluru or any other city in India. When stuck in congested traffic on the carriageway that was ironically meant to move them faster, people often wonder what the forest of concrete-and-glass buildings have come to mean. Tall towers everywhere, all at once. Homogenous vertical growth of cities that passes off as ‘development’ but erases local character and people’s access. This is visible and physical density; the impact it leaves can be disorienting.

India’s cities are among the densest in the world.[2] Across the top eight metropolitan regions, built-up area has doubled[3] – from about 2,136 square kilometres in 1995 to 4,308 square kilometres in 2025. In Delhi NCR alone, urban sprawl has added nearly 400 square kilometres[4] since the mid-1990s, while Pune has expanded by more than 300 percent.[5] Not only this, by 2050, the United Nations projects that over 800 million Indians – more than half the country’s population – will live in cities.[6]

Planners and policymakers invoke density as a buzzword. High density, they argue, makes cities modern, efficient, and globally competitive; the vertical skylines and jammed streets promise thriving business districts and higher GDP growth.[7] Density, then, becomes a synonym for progress. India’s National Building Code (NBC) calculates residential density as the number of dwelling units per hectare or number of people per hectare. Though people are the measure of density, they fall off the radar as top-down plans get implemented – that’s the flipside of density, a side rarely focused on.

For the large majority of people in cities, density means overcrowded homes with little or no ventilation, narrow streets brimming with cars and vendors, super-crush-load buses and local trains, crowded markets and recreation areas which are too few, and children forced to play in make-shift spaces outside homes. Unseen but unfolding simultaneously is the impact of density on the natural areas of cities, their ecology under constant attacks in the name of ‘development’ and construction – trees hacked, forests consumed,[8] water courses and lakes encroached,[9] salt pans under threat.[10]

What density means to people and nature, in terms of its impact, is not really measured. It unfolds here in a series of frames uncovering how a city shapes, squeezes and, sometimes, suffocates people who inhabit it; how density is experienced as a lived, daily negotiation; and what gets lost in the quest for denser cities. The frames attempt to ‘see’ density anew, from the ground up, in ways that do not manifest in plans and official documents.

Streets at capacity

From a quiet residential gully to a bustling market lane to the chaos outside a railway station, density reshapes streets into contested spaces. Notice (on the extreme left) how the children playing on the street are interrupted by cars – an all too familiar scene in Delhi’s urban villages or Mumbai’s crowded streets. In the market (middle frame), a plethora of vendors, carts and cars jostle for the same narrow strip of space seen in bazaars like Kolkata Bara Bazaar or Bengaluru’s Chikpette. By the railway station, commuters spill onto the road, and compete with cars and auto-rickshaws, much like the scenes outside Dadar in Mumbai or Sealdah in Kolkata.

Across these frames, it’s hard to pinpoint when the streets stop being a passage and become a battleground of bodies, vehicles, livelihoods and play spaces. Streets in India’s cities are a tapestry of chaotically woven activities of people and built forms. There’s not just the density of people but also the density of activities – almost none of which are formally planned for.

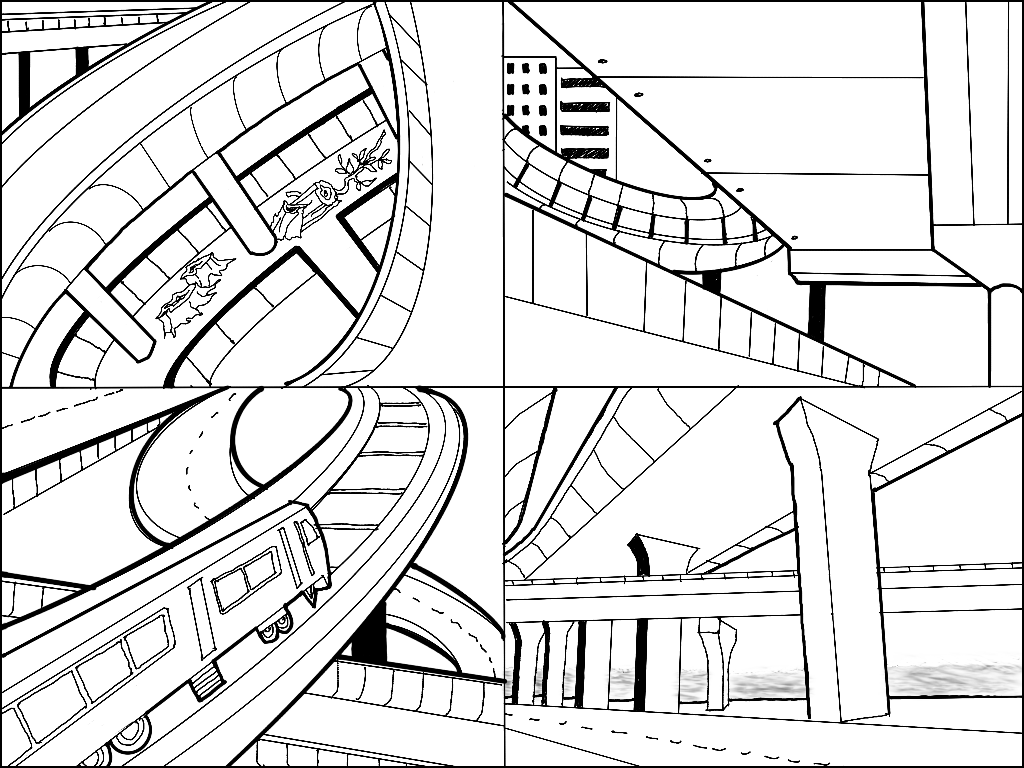

Infrastructure overload

Increasingly, our cities have flyovers, metro lines, bridges, and highways stacked on top of each other. They create a sense of ‘city on the move’ but, from a telescopic view, become a tangle of concrete over concrete. Did these frames look like abstract puzzles to you at first with curves and pillars folding into themselves? See, really see, what lies beyond. They echo the layered network of carriageways of Delhi’s Dhaula Kuan or Bengaluru’s Silk Board junction, or the dense weave of flyovers at Mumbai’s Bandra Kurla Complex or coastal road’s Haji Ali junction.

Infrastructure competes with itself, each new line or road laid over the last, the dense web of concrete above ignoring the human scale below, and adding to the urban stress. It promises connectivity but it’s a maze. Mumbai may be getting its metro network of nearly a dozen lines but, in the process, streets have been rendered uninhabitable with large potholes and construction debris strewn around, and metro pillars dangerously close to existing buildings. This has created dark and dingy spaces underneath the metro bridges and flyovers. Streets once covered with canopies of trees have become bare and unfriendly to people, their welcome density hacked down.

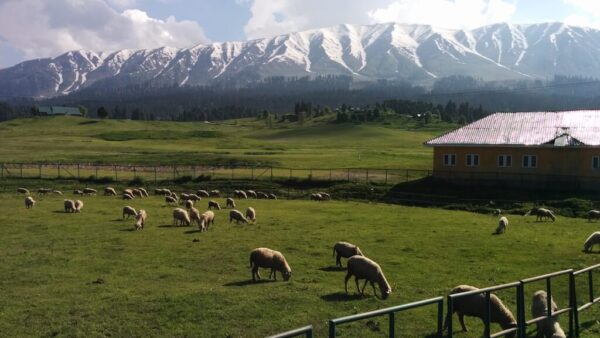

Where did our green go?

Urban forests like Aarey and Sanjay Gandhi National Park in Mumbai, Chandaka in Bhubaneswar, Dol ka Badh in Jaipur, and Kancha Gachibowli in Hyderabad have been in the news for the repeated attacks on them sanctioned in plans. The forests are a part of the city’s fabric – a truth rarely seen by planners. Diminishing them does not carry a cost, goes the neoliberal mantra. But that’s because, as environmental economist Dr Pavan Sukhdeo once remarked, nature does not send us an invoice.

As forests and green areas are made to shrink or disappear from our cities’ maps, generations will grow up without a memory of a pivotal element in the urban geography. The panel draws out the experience of a boy visiting his hometown after many decades and seeing that the forest, which was once out of limits and children were warned to not enter after nightfall, has been rendered unrecognisable. Roads cut through ‘his’ forest, tall towers have been constructed at its edges, and he wonders whatever happened to the mind-boggling variety of life, the complex web of biodiversity, that once thrived inside it.

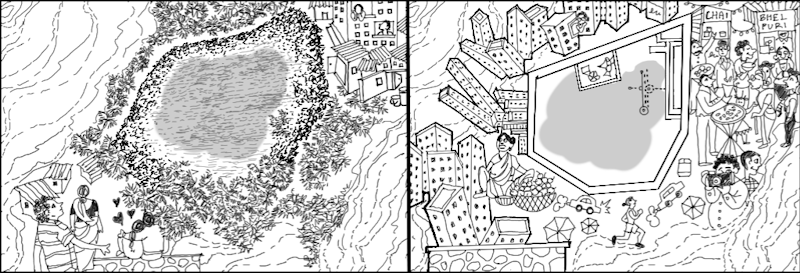

Lake edged out

Urban water bodies are disappearing as the density mantra moves in to landfill for more and more construction. This frame imagines how lakes across Indian cities have transformed, whether in Bengaluru or Thane or any other city. In the first, the lake is held by a soft, irregular boundary where vegetation grows thick, paths form organically, and the water is part of the landscape. In the second, the edge is ‘straightened out’ and concretised, made easier for people to walk but harsher for the lake itself. Buildings, stalls and shops start to crowd the lake’s perimeter, turning the natural space into a commercial strip. Every lake beautification and riverfront development in cities has meant such hardened embankments replacing the wetlands, leaving less room for water, species, and people to coexist.

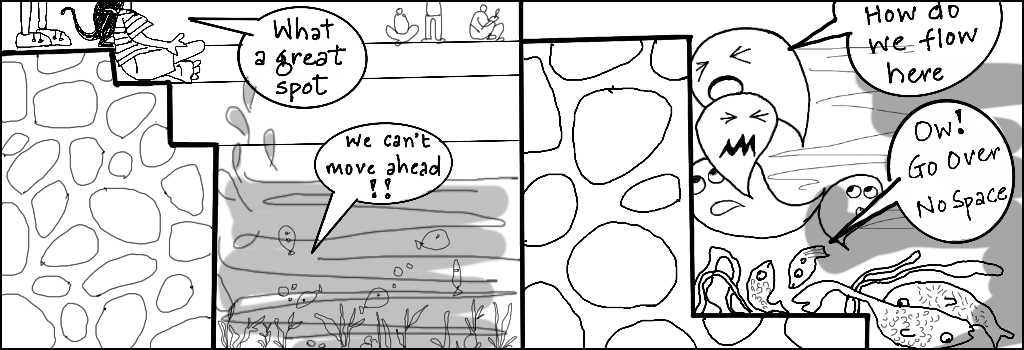

Where will the waters go?

What looks like a leisure spot for people, perhaps at a ‘developed’ riverfront or lakefront or seafront from a viewing platform (left) becomes an obstacle for water itself. Water droplets struggle, collide, and finally complain: “We can’t move ahead!” At Marine Drive, Mumbai’s iconic leisure spot, the sea finds itself hemmed in by tetrapods and concrete walls, with no room to breathe. It mirrors the fate and current craze for riverfront development whether in Pune’s Mula-Mutha, the Ganga in Kanpur, or Phase 2 of the Sabarmati in Ahmedabad where natural edges have been walled in by concrete embankments. When water has no space, it finds its own way, often flooding cities. As we try to contain water and tame it, it rises and takes over land creating its own way through cities, homes, mountains and villages.

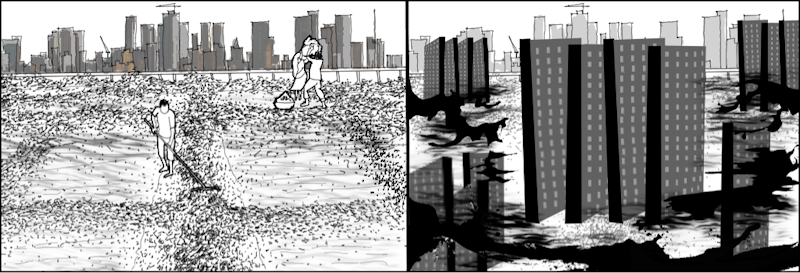

Flooded futures and mal-vision

In the first frame, salt pan workers do their tasks against Mumbai’s skyline. These lands have buffered the city from worse floods. However, the ongoing plans to allocate 256 acres[11] of Mumbai’s salt pan land for the Dharavi redevelopment project, for building housing for the slum dwellers, environmentalists warn, will only intensify flooding in the city. On the right, the centuries-old saltpans which were holding areas for water give way to high-rise SRA buildings with floodwaters rushing in – a warning of what is to come in the future. These salt pans, the city’s defence in heavy rains, kept the ecological balance but the current vision of ‘development’ sees them as wastelands to be put to maximum use. This is not a vision, it’s a mal-vision.

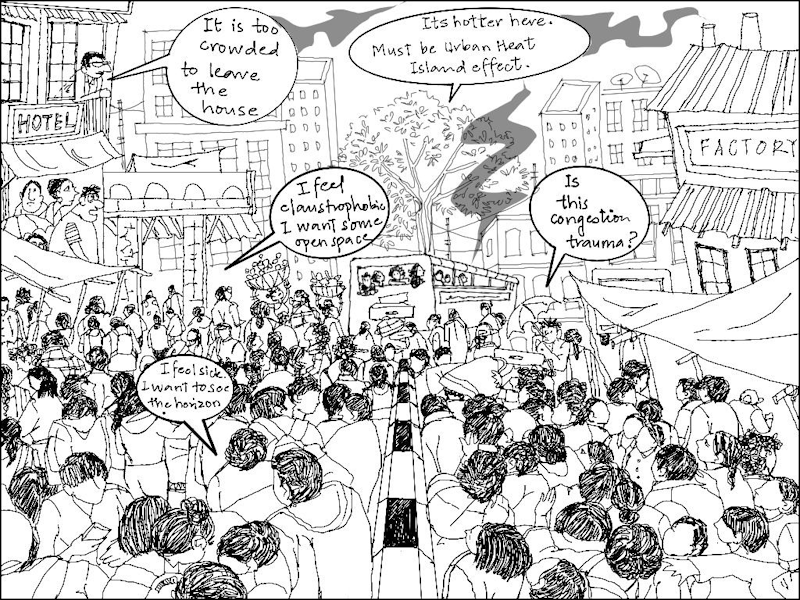

Multiplicities of density

Across cities, density leaves an impact on people’s health, relationships, and ability to live a good life. Trains, buses, streets, markets, even recreation spots are so densely packed, especially at certain hours of the day or some days, that people experience what urbanists are now recognising as ‘congestion trauma’. This trauma and disorientation makes people overstimulated, anxious, and edgy with exaggerated responses such as road rage. With little to no green around, no water bodies, the eyes are constantly tired of seeing concrete buildings and other people. With trees hacked, heat levels rise too making for the Urban Heat Island effect which worsens the trauma. From physical health and mental well-being to people’s productivity and collegiality, density affects everything. These would show if it was measured in these terms.

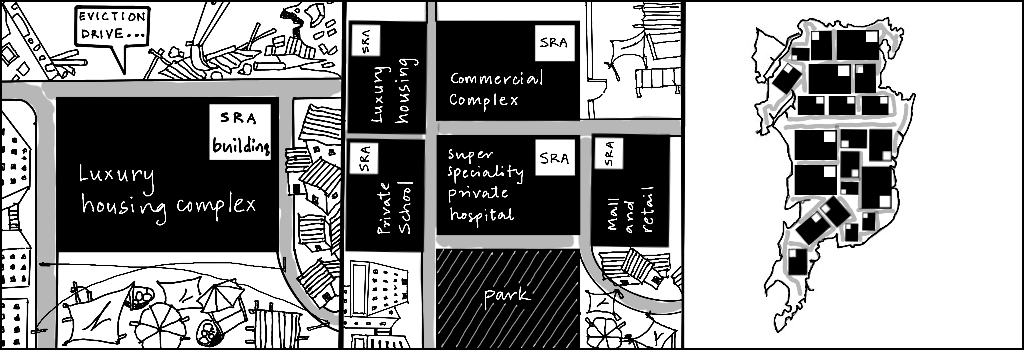

Flattened cities, flattened lives

A single plot is carved up disproportionately: A tiny portion ear-marked for slum rehabilitation or SRA housing while the maximum area is for building market-oriented housing and commercial complexes. The gates of these high end facilities are in turn always shut for those who live in SRA buildings, pushing people into a deeper and dangerous divide. Pull back from one plot and see a neighbourhood, or the city. More such plots appear, cleared through eviction drives, and stitched into this template. From above, the city flattens into a grid of identical blocks, with high density for the poorer SRA buildings and more space for the commercial ones, or old buildings redeveloped as new towers with mind-boggling densities. Gradually, neighbourhoods lose their distinctiveness.

Overall, what emerges is a mass produced city – dense, unequal, stripped of character. This densification is passed off as revival of land from its underuse. But how is a city densified and for whom are questions rarely, if ever, examined. Seeing density unfold in its various elements, like an anatomy study, is the first step to begin engaging with the questions.

Nikeita Saraf, a Thane-based architect and urban practitioner, works as illustrator and writer with Question of Cities. Through her academic years at School of Environment and Architecture, and later as Urban Fellow at the Indian Institute of Human Settlements (IIHS), she tried to explore, in various forms, the web of relationships which create space and form the essence of storytelling. Her interests in storytelling and narrative mapping stem from how people map their worlds and she explores this through her everyday practice of illustrating and archiving.

Illustrations: Nikeita Saraf