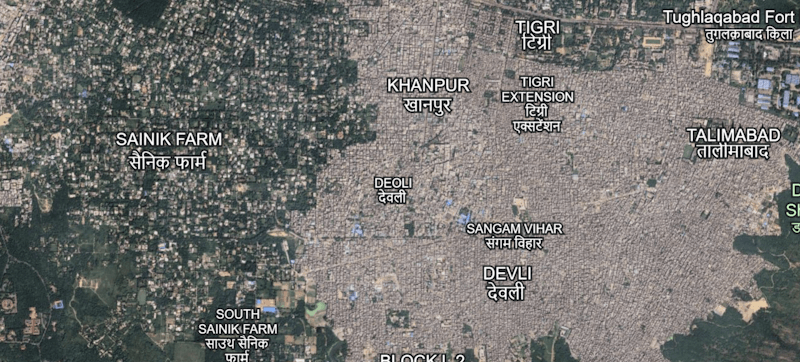

In South Delhi, these two colonies could not be more starkly different – Sangam Vihar and Sainik Farms. Two unauthorised neighbourhoods separated by barely a kilometre but so dissimilar, in fact diverse, in their character, profile of inhabitants, along with varied meanings of density.

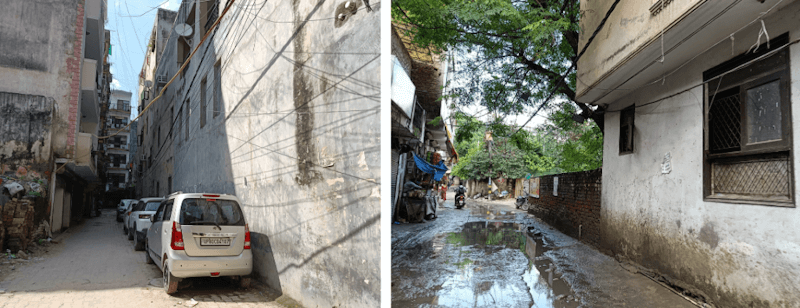

Sangam Vihar’s landscape is crammed with narrow lanes, open drains, with homes stacked five-six floors high with barely any natural light seeping in. There are no public open spaces, and piles of garbage lie unattended. Shivam Kumar, who has lived here for a decade, lists the routine injuries from potholes and the struggle to get an ambulance through the three-meter-wide lanes. The roads are broken and a trip to the nearest government hospital can take almost an hour. Four private water tankers roll in the span of 30 minutes one afternoon. Ritu says the supply is “erratic and expensive”.

A kilometre away, Sainik Farms, where the well-heeled live, sprawling farmhouses are encircled by non-native palm trees behind high walls, expensive cars glide through leafy streets, there’s an audible chorus of birdsong, and a few residents leisurely walk with their headphones on. There’s space here for life to unfold as it should, with the basic amenities taken care of, the benefits of a low-density neighbourhood.

This contrast is not unique to Sangam Vihar and Sainik Farms. Across Delhi, high-density settlements sit cheek by jowl with low-density enclaves – the congested neighbourhood of Kotla Mubarakpur beside the posh Defence Colony, the crowded Zakir Nagar, Taimur Nagar and Khizrabad next to the well-off New Friends Colony or the bustling lanes of Uttam Nagar in West Delhi adjoining Dwarka, a planned sub-city. This is a patchwork of extremes in land use and layouts.

Globally, in Brazil’s Sao Paulo, the densely populated Paraisopolis favela,[1] home to over 60,000 residents, is situated adjacent to the upscale Morumbi district. Despite their proximity, the residents of Paraisopolis face challenges of inadequate infrastructure and limited access to services while Morumbi boasts well-maintained roads, green spaces, and comprehensive amenities. In Jakarta, Indonesia, dense urban villages known as Kampungs,[2] exist right next to high-rise skyscrapers.

Why does density shift so drastically within a kilometre? Do we see this in our cities? Importantly, when both the high and low density neighbourhoods are irregular or unauthorised, only residents of the former are forced into a sub-standard quality of life. It follows, then, that density is not a factor of geography alone; it is an outcome of complex socio-economic factors from government policies to economic stature of people and the city’s willingness to provide for them.

How density shifts

Sainik Farms is among Delhi’s most prominent examples of an affluent unauthorised colony;[3] others include Mahendru Enclave and Anant Ram Dairy. These are areas with over 50 percent plots larger than 350 square metres inhabited by ‘affluent persons,’ according to the KK Mathur Committee Report of 2006.[4] Delhi’s municipal corporation does not provide public services here; the residents fend for themselves, they can afford to.

Unauthorised colonies, both wealthy enclaves like Sainik Farms or less privileged settlements such as Sangam Vihar, share a similar origin story. Urban researcher, Gautam Bhan wrote how they mushroomed[5] on agricultural or common land that was sold by farmers to developers or residents. While the transfers were seemingly legal, they violated Delhi’s planning laws on land use, zoning, and building norms. The colonies carried the ‘unauthorised’ tag. But it meant differing densities and a lack of essential amenities in one but not in the other.

Sainik Farms, distinct in scale and elite character, was established in the 1960s as a cooperative society[6] for retired defense personnel, war widows and soldiers with disability. It was envisioned as farmland with modest housing. Over time, the farmland was carved into plots, resold, and developed into sprawling mansions. The cooperative’s 102 farm plots spanning 161 acres expanded into roughly 1,500 acres,[7] making it one of the largest affluent – unauthorised – enclaves in Delhi where ministers, judges, and bureaucrats reside. This is what scholars call “elite informality,” writes Vivek Mishra in Class, Property Rights and Citizenship: Affluent Informal Settlements and the Cultural Production of Property in Delhi.[8]

There have been attempts to regularise the neighbourhood but its status has not influenced its density or services.[9] What the state does not provide, resident welfare associations manage through private contractors. Its languid tree-lined lanes are named “Palm Drive” and “Country Club Road,” with interlocking concrete pavements, and trees shading large farmhouses. To merely walk here is like being in another world. Only domestic workers hurry to the gated villas to work. Nothing about Sainik Farms looks unauthorised nor does life manifest this way.

Unauthorised or unregularised decides density

Walking around in Sangam Vihar, one of Asia’s largest unauthorised colonies,[10] is a different experience. Absent roads, open drains, jammed traffic, and waste littered around. Spread across just five square kilometres but home to nearly a million people, its density works out to an astonishing 2,00,000 persons per square kilometre. The settlement came up in the late 1970s and grew rapidly thereafter on agricultural land of Tigri, Deoli, Tughlaqabad and Khanpur villages.[11]

Residents here struggle with poor service delivery. Kumar says that water supply is a perennial issue and the “water tanker mafia[12] does not allow water to reach people. The roads are unimaginably narrow. Ambulances will barely reach us in time because of the high congestion,” he says. “Politicians only come here during elections, otherwise no one cares about us,” shares another resident.

Sainik Farms’s streets are also narrow but residents built internal roads themselves. Here too, residents depend on private tankers for water. Ratan Kohli, a resident of Sainik Farms and treasurer of Western Avenue Residents’ Welfare Association here, was concerned that their roads are used as thoroughfare by people in areas like Sangam Vihar which adds to the traffic congestion.

“Elderly people live here. We worry about ambulances reaching us or us reaching the nearby hospitals,” says Kohli. However, except in the peak hours, there’s hardly any congestion; street vendors are barred, commercial vehicles face tolls, and entry points are tightly controlled. Sainik Farms is what urbanists refer to as the low-density urban sprawl, where buildings and people are fewer and spread apart. Sangam Vihar, on the other hand, is the typical high density slum-like settlement with barely any breathing space between buildings and crowds.

Dr P.S.N Rao, Dean, School of Planning and Architecture in Delhi, explains that unauthorised colonies emerged in the gaps left by formal planning: “The government plans for low to medium densities. Those plans include parks, schools, playgrounds and open spaces. But because there’s a huge demand-supply gap and planned housing is too expensive, people are forced to look for cheaper alternatives. Landowners with a few acres subdivide their plots, carve out narrow lanes, and sell them off. As a result, Delhi today has nearly 1,800 unauthorised colonies.” Almost all show high densities.

There have been efforts by the government to regularise the unauthorised colonies through the Pradhan Mantri Unauthorised Colonies in Delhi Awas Adhikar Yojana (PM-UDAY) launched in 2019, to grant ownership rights to residents. As many as 1,731 colonies were identified; Sangam Vihar was one of them.[13] Sainik Farms, however, was not; its exclusion prompted residents to move court. In August, the Delhi HC criticised the Centre for dragging its feet on deciding on the neighbourhood’s fate.[14]

Curiously, the language used to describe both settlements are different. Sainik Farms is described as an “unregularised” farm colony, while Sangam Vihar carries the stigma of being “unauthorised”.[15] As urban geographer and City Sabha founder Saleha Sapra notes, “These labels aren’t just technical – they reflect the politics of how certain settlements are perceived and classified. It is also called an ‘affluent colony’. Because of its affluence, it’s not recognised by the PM-UDAY scheme. That’s where the difference in perception of classification lies.”

Despite the stark density divide at the social and human scale, the relationship between the two is of interdependence: The former relies on the latter’s routes for water tankers while Sainik Farms depends on domestic workers from Sangam Vihar.

Urban villages and density

Nearby Sainik Farms are Neb Sarai and Saidulajab, urban villages which include unauthorised residential colonies like Freedom Fighter Enclave and Paryavaran Complex, along the busy IGNOU Road. While Freedom Fighter Enclave is relatively low-density, parts of Paryavaran Complex and the surrounding areas are far more congested.

In the former, apartment sizes range[16] from 1,050 to 2,400 square feet each across about 2,500 flats, there are wide roads and many parks, and it does not flood during rains. Apartments have balconies overlooking Delhi’s green belt. By contrast, Paryavaran Complex packs nearly[17] 2,300 flats into much smaller units, many between 550 and 1,800 square feet, along narrower lanes, a single park, and regular flooding and potholes.

As these areas fall under the lal dora category – a colonial era designation separating residential parts of a village from its farm land – Sapra explains that many planning norms do not apply. Buildings do not require municipal approval nor are they subjected to house tax if they are under 200 square metres. “Many of Delhi’s urban villages have been reclassified as ‘urbanised’ but little has been done to develop them. They have extremely dense congested housing with no ventilation or sunlight. As the city expanded, these villages grew organically, with buildings rising five or six storeys high and basic services not reaching residents,” says Sapra.

An issue of urban planning

High density urban planning, also known as the compact city model, has caught the fancy of urban planners who cite its advantages such as reduced travel times, lower carbon footprints, and more efficient land use. However, planned and sanctioned high density areas are not imagined like Sangam Vihar but like Rohini. Here, very small plots were grouped into many sectors creating a form of high-density living but in a planned way making optimal use of land. That said, such examples are rare. In Dwarka, the density is high but the housing stock is geared toward higher-income groups.

Nidhi Batra, urban designer and founder of Sehreeti Development Practices, attributes the history of how both settlements came up as the cause of its differing densities. “Sainik Farms was given to defence personnel, meant more as farmland, almost like Chhatarpur. Over time, these turned into residential farms and lavish bungalows. Sangam Vihar began as an urban poor settlement, now turning middle class. Over time, all the greenery and wetlands the area once had have been lost. All unauthorised colonies are not the same. That’s the irony. Even illegality has access and privilege,” she explains.

Increasing density in a neighbourhood without a parallel investment in public infrastructure erodes the quality of life and prioritises profit over people, she explains. She warns of the growing preference towards Transit-Oriented Development that clusters high-density housing, offices and commercial spaces around metro and transport hubs. While it promises efficiency and reduced car dependence, Batra argues that, in Indian cities, it sidelines the questions of inclusivity, sustainability, and quality of life.

“Across the world, there’s a growing demand for slow cities with urban green spaces seamlessly integrated with public transport. In Bogota, they first invested in bike lanes and a green network through the city, then expanded the Bus Rapid Transit system,”

Batra points out, while TOD is meant to strengthen public transport use, the government is doing the opposite. How these high densities will be managed is anybody’s guess.

There has to be political will to address the lack of affordable housing and robust urban planning first, warns Dr Rao. “Agencies should start by assessing actual demand and plan accordingly. In India, the need is always for low-and-middle income housing. That’s why small plot sizes and planned high-density living should be prioritised but this rarely happens because housing is a deeply politicised exercise,” he explains.

In Sainik Farms and Freedom Fighter Enclave, such niceties and legal status do not impact lives; in Sangam Vihar and Paryavaran Complex, they do.

Ankita Dhar Karmakar, Multimedia Journalist and Social Media in-charge in Question of Cities, has reported and written at the intersection of gender, cities, and human rights, among other themes. Her work has been featured in several digital publications, national and international. She is the recipient of the 4th South Asia Laadli Media & Advertising Award For Gender Sensitivity and the 14th Laadli Media & Advertising Award For Gender Sensitivity. She holds a Master’s degree in English Literature from Ambedkar University, New Delhi.

All photos: Ankita Dhar Karmakar