We are faced with testing times across cities in India with a direct risk to the health and well-being of people from the degrading quality of urban environments coupled with the lack of good quality affordable housing for the masses. Mumbai, the financial capital of the country, is a metropolis where these issues are compounded. The housing need of most of the city’s population has been ignored over the years in the development agendas prepared by policy makers and governments.

Mumbai is an unplanned city. Its development has generally been ad-hoc and arbitrary. Interestingly, the very first signs of urban planning in Mumbai emerged as a response to the devastating plague in the late 1890s that caused a high number of deaths and the working class fleeing the city, leaving the poorer neighbourhoods devastated. Commerce and industry were threatened by this mass exodus which forced textile mill owners and city elites to address the state of housing and sanitary conditions. We are now faced with a similar social catastrophe of deteriorating conditions of daily life in Mumbai and in other cities.

Opportunities to rebuild

Similarly, also in the wake of an outbreak of tuberculosis and dengue in the early 1930s, New York city saw a fierce debate on the models of city planning to be followed. A city already used to high-rise living, New York was to become the epicentre of a revolution in state-driven, affordable, rental housing experiments. A prominent journal The World argued for transit-oriented development with a focus on decentralisation and a clear separation of work and living areas. On the other hand, Appleton’s Journal argued that “no means of transit could bring people together for social purpose that would meet the needs of a scattered community — hence the model of the ‘ideal city’ as proposed by The World would be prone to divide interest, weaken intercourse, and abridge the pleasures of people”.

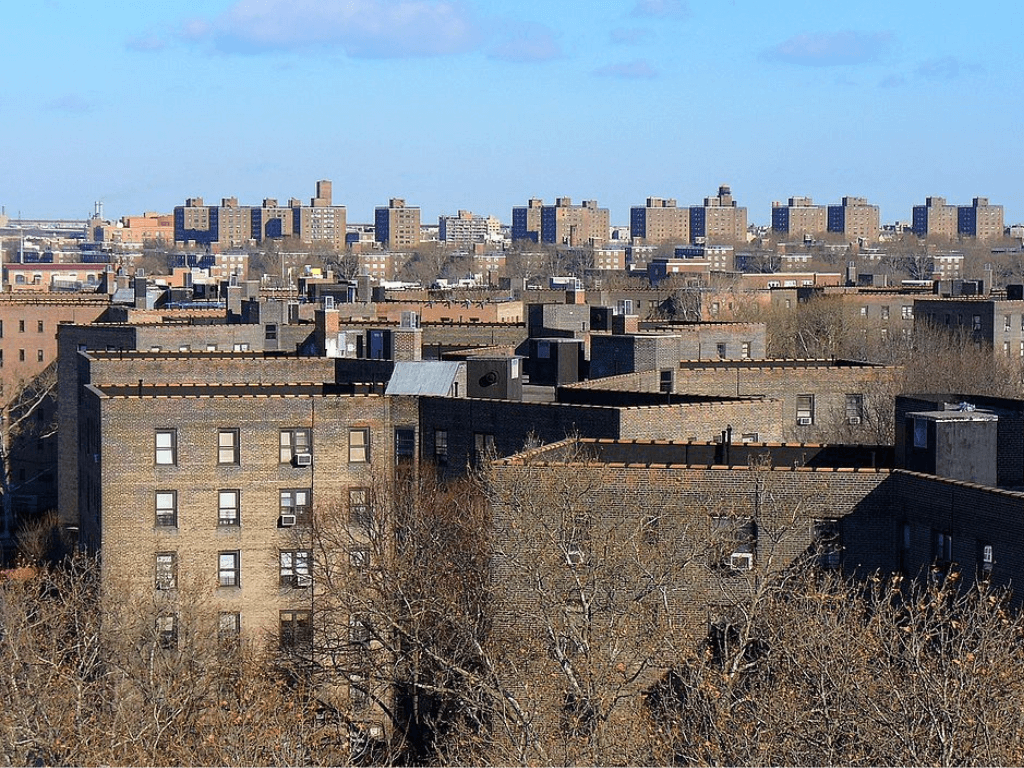

City life was to include access to amenities for intellectual growth – cinema, theatre, libraries, art galleries, promenades, restaurants. This, along with the pressure on housing to combat disease, saw the evolution of one of the most prominent housing typologies globally — the ‘Tower in the Park’. As claimed by the slums clearance departments under Robert Moses – high-rise housing for the lower income groups promoted hygiene with “sun, space and green that could foil the incubation of germs”.

The commons enable a robust and active life and, in turn, become the lifelines of our communities. Worldwide, the most successful city developments have realised the importance of mixed-use and the relationship of housing with the city. Shared common spaces give people a sense of belonging and commonality of purpose, and reflect the dignity accorded to collective effort and control. They are extremely important, in fact, essential today when privatisation has considerably downsized and undermined these spaces as cities expand. Housing must become an essential part of the ‘commons’.

New York holds a lesson and Plunz’s book details the developments. The Municipal Housing Authority Act of 1934 led to the formation of the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) after the Great Depression. The head of NYCHA’s technical staff at the time, Frederick Ackerman, focused on evolving housing patterns through rigorous case studies while challenging prevalent patterns of perimeter housing with gardens inside. Design competitions were held to empanel architects for NYCHA. Design entries showed borrowed influence and knowledge from global trends like in London where public housing was a key focus. Rigorous case studies and constant upskilling are indispensable elements of any design process and were practiced by public authorities at the time in New York City. Unfortunately, we see neither from state agencies in Mumbai even as it hurtles down a perilous path of becoming an un-liveable city.

On the survey of 58 dwellings as the best way forward for social housing, Ackerman observed the “incongruous relationship between the inevitable cost-of-use and the incomes of those for whom the projects were designed” and stated that “this survey makes one thing plain- technique cannot solve the problem as stated. It must first be stated in congruous terms: Incomes of the lower income groups must be raised and the cost-of-use must be cut down – one or both.” We see a similar narrative emerging in Mumbai, seven decades later, as the current models of slum redevelopment has led to uninhabitable buildings.

Photo: Studio A+H

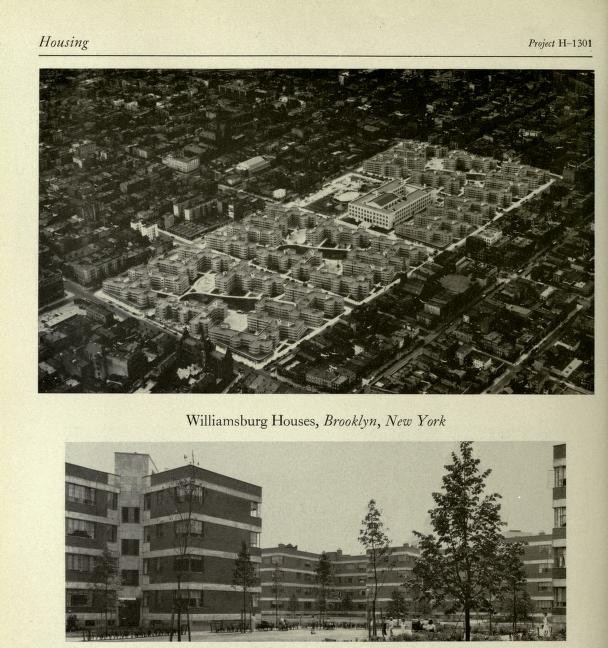

State agencies in NYC evolving typologies and challenging prevalent trends showed how progressive they were. The state set the benchmark; the private players followed suit. Despite the relatively small size of the Public Works Administration (PWA) program, it contributed significantly to the development of various housing design methods and laid the foundation for the more extensive federal housing works that followed. Examples such as Flagg Court Housing and Harlem River Houses were standout developments that dealt with various aspects of housing along with social needs to sustain city life. However, through projects such as Williamsburg Houses which caused a clear “schism in the neighbourhood because of its illogical shift from the gridiron of the rest of the city”, NYCHA showed that even a progressive housing authority faced a constant battle with architectural identity and placelessness. As Plunz states “The absurdity of the gigantism aside, this scheme typified the manner in which the new European work came to be misapplied in the United States.”

Mumbai’s Slum Rehabilitation policy and plot-based development strategy have overlaps with the New York model and some of its more oppressive moves in the evolution of affordable housing such as the ideas of standardisation, professional fees for architects based on repetition of unit plans and blocks rather than a response of architecture and housing to the context, deriving design through methods of construction economy, stripping cultural and commercial aspects from housing without any focus on creating neighbourhoods conducive to city life, and most importantly, using housing as a means of social control.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

State’s responsibility

Public sector initiatives can lead the way while taking responsibility for promoting models of development that are in the best interest of user groups. Pro-active moves of planning authorities such as planning manuals like PWA’s ‘Unit Plans’ — a catalogue of acceptable design possibilities for repetitive housing units — were encouraged. PWA ‘simplified’ the planning process with rigorously defined criteria such as no through traffic and specification of 25 percent site coverage which fulfilled the social reformers’ goals of the city in the park.

However, it also meant that any unitised building design could work on any site and this “facilitated the bureaucratic acquisition of design control.” PWA’s reducing fee structure with increasing size of projects encouraged architects to repeat their apartment clusters on open sites – and discouraged them from breaking away from this for larger housing projects which were less well-funded.

Based on the PWA experience, government initiative in housing became a permanent reality in 1937 when Congress passed the law, the United States Housing Act (USHA), to set up a permanent structure for federal low-rental housing in which state and local authorities were empowered to administer federal programs. The NYCHA became the local implementation authority for low-income housing, supervised by the federal government. This model proved to be tremendously successful. In just 20 years, from 1937, a total of 33,350 low-rent apartments were built and, by 1985, the NYCHA operated a staggering 1,65,892 apartments. This was social housing in one of the world’s most capital-worshipping cities.

In Indian cities, the state needs to step up and take responsibility for providing social housing for the masses. The myth that the private sector will perform social good and the work of the state has been exposed in the last 30 years in Mumbai’s slums rehabilitation and this failure has directly contributed to the proliferation of slums. Mumbai’s current land occupation shows that two of the city’s largest land banks are (i) land under slum occupation across approximately 2,660 hectares or 27 square kilometres and (ii) land under Maharashtra Housing and Development Authority (MHADA) which is approximately 1,520 hectares or 15 square kilometres. Together, they add up to approximately 4,000 hectares or 40 square kilometres — almost 40 percent of the tenable 110 square kilometres, based on ‘Open Mumbai’ data.[1] This presents the state an incredible opportunity to promote equitable and well-designed affordable housing on land under its jurisdiction – if it wants to.

Photo: Short and Brown

Focus on well-designed housing

Architecture must be specific to its location and context. It is the responsibility of the state to not only deliver housing for the masses but also housing that meets the highest levels of health and sanitation. Basic levels of light and ventilation must be achieved. In our climate, it is imperative to provide windows on either side of rooms for cross ventilation, including the kitchen. In several rehabilitation projects, there are innumerable cases of tuberculosis and other ailments coupled with ‘congestion trauma’ due to poor design.

In NYC with the surge of affordable housing requirements, NYCHA was soon overcome by maximising economies of scale and the quality of housing/tenement and construction had to be compromised. Costs had to be curtailed, and this directly impacted project liveability. While the ‘Tower in the Park’ typology met the goal of natural light and ventilation for housing blocks, it produced large undefined open spaces which were loosely dealt with as parks/gardens and lacked the social intensity seen in the tenement streets they replaced. As critiqued by Plunz “These spaces propagated crime since the scale of towers prevented the normal exercise of family territoriality with the removal of large numbers of units from visual contact with open space prevented public vigilance. With the social housing programs of the 1950s the use of housing as a source of social control had reached its most deterministic phase. Housing design has always been a social derivation of architectural form.”

In 1961, a new zoning resolution was passed that further encouraged use of high towers with parks in between. Importantly, this scheme saw the advent of Floor Area Ratio (FAR) and offered a ‘bonus’ system to the developer to increase the open spaces on a plot in exchange for taller and slimmer buildings – this saw the production of up to 35 storied towers for low-income rental housing. This happened at a time when the ‘Tower in the Park’ concept was already under critical scrutiny after two decades of implemented projects – and shows a lag between building practice and its institutionalisation in legal terms – a trait often seen in cities where development is driven by market forces and changing construction technologies and is rarely tracked by state agencies and policy makers. While over 60 years have passed since its critique, FAR or Floor Space Index remains the primary tool to incentivise housing, hand in hand with profits of developers in Mumbai.

Ensuring comprehensive participatory and inclusive planning

Jane Jacobs’ advocacy helped spur a housing movement in the early 1960s that focused on bringing back the qualities of low-rise high-density housing that generated ideal city life with social interactions. Through private endeavours and architectural competitions, the ‘Tower in the Park’ typology began to decline. Jacobs’ concept of ‘eyes on the street’ stressed the crucial importance of a vibrant street life to neighbourhood safety and community.

Examples of sensitive high-rise developments in the 1970s began with a response to low-rise context surrounding new sites, and creation of smaller-scale open spaces. A significant project that furthered these concepts and referenced in Plunz’s book was Richard Meier‘s Twin Parks Northeast Housing which in the words of the architect was “not an architecture of isolated structures – here there is reference to ideas of traditional building, preoccupation with urban continuity and concepts of adaptive capability”.

Comprehensive planning with site and context responsive design endeavours will ensure the production of a dynamic built environment in the city. Communities are built over decades by people living in them and the social structures built into these spaces are complex – which contribute towards transforming a ‘space’ into a ‘place’. The current models of ‘affordable housing’ in Mumbai have led to the standardisation of housing units and layouts across projects. The new standardised 330 square feet units completely disregard existing occupation patterns and lead to the destruction of livelihoods. Site planning is completely abandoned leading to stacking of monotonous blocks with minimum open spaces between buildings as permitted within rules.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Way forward

State agencies should now chart a roadmap for a far more sustainable and healthier Mumbai of the future, and ‘housing for all’ must be a key mandate. The production of affordable, well-designed urban housing must become a priority. Open spaces and amenities that sustain daily life referred to as ‘the commons’ must become the basis for all developments within cities. This shifts the focus away from simple production and ‘monetising’ of housing towards creating sustainable and resilient communities with higher levels of dignity accorded to individuals and their collectives.

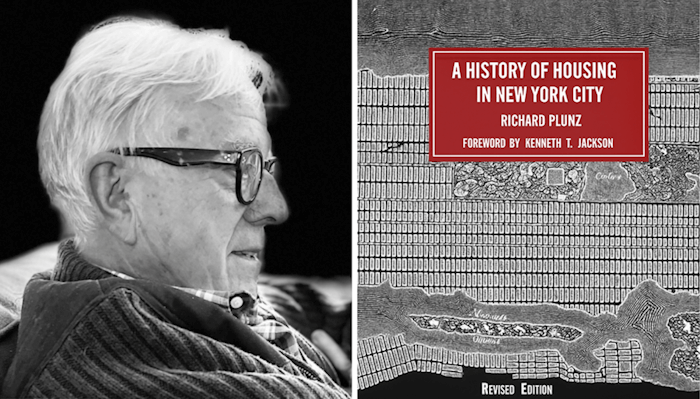

As Plunz writes in the conclusion to his book: “Today, we are equipped with technology as well as the understanding of the complex interplay of society, economics, and design – what is missing is the political initiative to use them”. For us in Mumbai this stays true 35 years after his book was published. The true power of design is ever more asserted when the processes of design are collaborative in all aspects. After all, we hope that a decade from now we don’t find ourselves amidst more severe social catastrophes having repeated the cynical mistakes of the past.

A History of Housing in New York City by Richard Plunz. 1990. 422 pages. ISBN 978-0-231-06297-8 (pbk.) Columbia University Press, New York

Samarth Das is an Urban Designer and Architect based in Mumbai. He has completed his Masters in Urban Design and Architecture with Honors from the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, Columbia University in New York; and his Bachelor of Architecture with Honors from KRVIA in Mumbai. Having practiced professionally in Ahmedabad and New York City, Samarth’s body of work at PKDA Architects in Mumbai over the last decade focuses on engaging actively in both public as well as private sectors – to design articulate shared spaces within cities that promote participation and interaction amongst people.

Cover photo: Queensbridge is an example of the ‘Tower in the Park’ housing typology that promised sun, space and green as antidotes to urban disease. Credit: Wikimedia Commons