Living in the lap of nature and interacting with it on an everyday basis allows us human beings to form a unique relationship with it. Here, nature does not stand separate or distinct from human life but is woven into people’s everyday actions and decisions. Stories abound in almost every old community and culture that speaks of nature, its abundant or scarce flora and fauna, nature as a willing comrade at times and a fierce adversary at others.

The older the civilisation and community, the older such stories – of groves being worshipped and protected in villages, of animals and reptiles treated with reverence, of communities thanking a hunted animal because it laid down its life to satisfy their hunger, of seas calmed down with prayers before the fishing season starts, of rivers basins and forests treated as out-of-bounds to save their ecological wealth, and more. Nature was woven into cultures and this philosophy, of humans as a part and parcel of nature, was passed down generations.

Communities and countries in the Global South show this more than the leading nations of the industrial revolution and modern urban world where human beings have sought to control nature for its resources; in the former, nature meant resources but also sustenance and culture.[1] Emergencies or crisis in nature, therefore, also meant an existential crisis, a cultural loss. Questions of the environment, especially climate change in the past few decades, in these communities became questions of livelihoods and life itself.

Environmental movements or mobilisations have, therefore, overlapped with social movements for justice and peace, with the poor trying to safeguard natural resources against takeover by the state or the market. In the Global North, environmentalism has been, till recently, about the wild, wildlife and its preservation – an elitist approach. The South-North divide in environmentalism was articulated back in 1997 in the book Varieties of Environmentalism: Essays North and South by Ramchandra Guha and Joan Martinez-Alier who argued that “the environmentalism of the poor originates in social conflicts over access to and control over natural resources”.

With examples drawn from Asia and Latin America, they showed why the world’s poorest citizens were not “too poor to be green” as was assumed by the west, especially the United States, and that conservation of biodiversity and environment was not exclusive to the affluent west. Environmental movements and struggles against climate impact have lately divided the two parts of the world.

‘No damage in Sussex or Finland, damage in Congo, Indonesia’

Environmental and climate struggles in the Global South mirror colonial struggles, as anthropologist Jason Hickel remarked in 2024 while explaining how capitalism and ecological crisis are linked and why Palestine is at the centre of it all.[2] “The Global North – the Imperial Core – specifically their ruling classes are responsible for the excess emissions and resource extraction driving the climate breakdown,” he remarked, adding that “half of the resource materials used in the ‘core’ is net appropriated from territories in the Global South which causes severe damage. You don’t see this damage in Sussex or Finland, you see it in Congo or Indonesia. The core benefits while everyone else suffers,” said Hickel.[3]

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

This characterises environmental movements in countries of the Global South, across South America, Asia, and Africa – a fight for land and water, for social justice. Their forms, methods and values are different from environmentalism in the Global North. It’s no surprise then that the maximum number of environmental defenders attacked, killed, have been from here. In 2023, according to the Global Witness report,[4]166 of 196 environment-related killings were from Latin America; of the 166, 122 were in countries of South America alone with 79 in Colombia, 25 in Brazil and 18 in Mexico. “The new figures take the total number of defenders killed between 2012 and 2023 to 2,106,” revealed the report.

“Environmentalism—a cultural feature developing in the Western world since the mid-19th century—has come to be, between the late 20th and early 21st centuries, both a global expression of this awareness and a sum of glocal political movements,” stated this paper[5] in Oxford Research Encyclopaedia in 2020. This “explains the regional features of its expressions. The European concern with eco-efficiency, for instance, and that of North America with conservation and the control of environmental risks and damages, coincide in this general panorama with African concerns for their colonial legacy, and the Asian vision of culture of nature as a component of a millennial civilisation. Latin America’s environmentalism, for its part, is closely associated with the demand for environmental justice and a political ecology approach to environmental conflicts,” wrote Panama-based Guillermo Castro H.[6]

“As the climate crisis accelerates, those who use their voice to courageously defend our planet are met with violence, intimidation, and murder. Our data shows that the number of killings remains alarmingly high,” pointed out the Global Witness report. It identified mining as the biggest industry driver, with 25 defenders killed after opposing mining operations in 2023. Others include fishing (5), logging (5), agribusiness (4), roads and infrastructure (4) and hydropower (2); in total, 23 of the 25 mining-related killings globally in 2023 happened in Latin America and “more than 40 percent of all mining-related killings between 2012 and 2023 occurred in Asia which is home to significant natural reserves of key critical minerals vital for clean energy technologies.”

The Escazú Agreement, a regional agreement on access to information, public participation, and justice in environmental matters in Latin America and the Caribbean, came into force in 2021. It ensures the rights of future generations to sustainable cities and environmental justice, along with protection of the environment and its defenders. However, the agreement is not ratified by nine of 25 countries including Peru, Brazil and Guatemala, although it is the riskiest region for environmental defenders.[7]

South America – environmental justice is social justice

South America, home to the second-largest river, the Amazon, and the world’s longest mountain range, the Andes, has mind-boggling biodiversity and natural landscapes. The region has seen environmental issues like rampant deforestation and desertification, soil erosion, glacial melting, water scarcity, and sea level rise, according to the leading environmental website earth.org.[8]

Besides the Amazon, the Gran Chaco, the continent’s second-largest forest spanning more than a million kilometres across Argentina, Paraguay, and Bolivia, has lost more than one-fifth of its forests[9] (around 1,40,000 square kilometres) since 1985; more than 60 percent of South America’s soil – including 18 percent of Brazil’s territory and 100 of 270 million hectares in Argentina – stands degraded threatening food security[10]; since the 1980s, the tropical Andes in Chile and Argentina have been retreating while Peru lost more than 40 percent of its glaciers; parts of South America have been dealing with droughts and unprecedented water crisis due to over-exploitation and large-scale industrial pollution of major water bodies like Medellin River in Colombia, Guanabara Bay in Brazil, and Argentina’s Riachuelo River; and sea level rise threatens cities like Fortaleza, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, and Porto Alegre in Brazil, Buenos Aires in Argentina, Santiago in Chile and Lima in Peru, the website details.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The International Seabed Authority was called to pause negotiations on the undersea mineral exploitation in 2023 to understand the impact of this extractive activity. Countries such as Mexico, Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Panama, and the Dominican Republic have signed in to call for a moratorium on deep-sea mining.

The Adapta Sertão initiative[11], a coalition of organisations and small farmers, was created to employ environmental regeneration strategies in the semi-arid Sertão region, one of Brazil’s driest areas. The “green transition” towards renewable energies has, ironically, provoked an unprecedented increase in extractivist projects[12] across South and Latin America. Faced with violations of their individual and collective rights, and the increase in natural disasters caused by global warming, indigenous communities and leaders across the region are mobilising to protect their territories and the environment.[13]

Ecuador – a post-extractivist future

In parts of the Ecuadorian rainforest like Napo and Orellana provinces, the major environmental challenges of mining, illegal extraction of gold and degradation of water bodies are made more dangerous by organised crime groups.[14] However, communities and independent media and activism alliances are joining forces for environmental justice. The Black and Indigenous Liberation Movement (BILM), an Americas-wide network of grassroots groups working together to fight extractivism, is an example.

Leonardo Leonel Cerda Tapuy, a young Kichwa activist and founder of the Black and Indigenous Liberation Movement (BILM)[15], has spoken of how indigenous communities in Ecuador are denied access to clean water, education, housing and electricity, and therefore people living in these situations “don’t have any other option but to resist and fight for (their) rights and the rights of the collective.” He told a policy dialogue session at Johns Hopkins University, “Since 2020, the Ecuadorian state has given over 148 new concessions for gold mines in Napo province. The local indigenous communities depend on these rivers for life: if our water is contaminated, it is certain death for us and our families.”

He emphasised the South-North divide, describing how they grow up in ancestral cultures that see humans not as the centre of the world, but as one element of it, but these cultures have been stripped of their rights in a colonised, capitalist world that doesn’t value people or the environment.[16]

Activists like him have advocated that protection of their land and resources means working towards “a post-extractivist future” and building “collective solidarity economies” not based in an extractivist mentality. An example is the “Sí al Yasunì” campaign to protect the biodiversity-rich area in Ecuador from industrial projects slated to extract oil; a popular consultation in August 2023 saw about 60 percent people choosing to halt oil exploitation.[17]

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Pacific Islands: Rising sea level, cyclones a threat

The islands in the pacific region have one of the richest complexes of marine as well as terrestrial ecosystems. As per World Meteorological Organisation, the sea level rise has raised cyclone threats and surface temperatures, but the increase in sea surface temperatures is three times faster than the global average and marine heatwaves have doubled in frequency, intensity and last longer since 1980. Along with the Pacific region, the ocean has taken up more than 90 percent of the excess heat trapped by greenhouse gases globally while undergoing irreversible changes[18] but this rarely makes it to global climate conferences.

Lagipoiva Cherelle Jackson,[19] a pacific islander, scholar and independent journalist from Samoa has been actively covering the climate crisis in the region and advocating for traditional solutions as well as the knowledge passed on through generations of the island inhabitants. Her homeland is one of the most exposed to present and future climatic changes. Despite Samoa’s vulnerability, the global media’s coverage has been negligible, she stated.

She also hosted The Guardian Australia’s award-winning podcast, ‘An impossible choice: the Pacific’s climate crisis’ which looks at the decision faced by Pacific people as climate change makes their islands unliveable: can we stay on our land or will we be forced to leave,[20] as well as wrote the first ever study of how the media in her country have covered climate change, entitled ‘Staying afloat in Paradise: Reporting climate change in the Pacific’.[21]

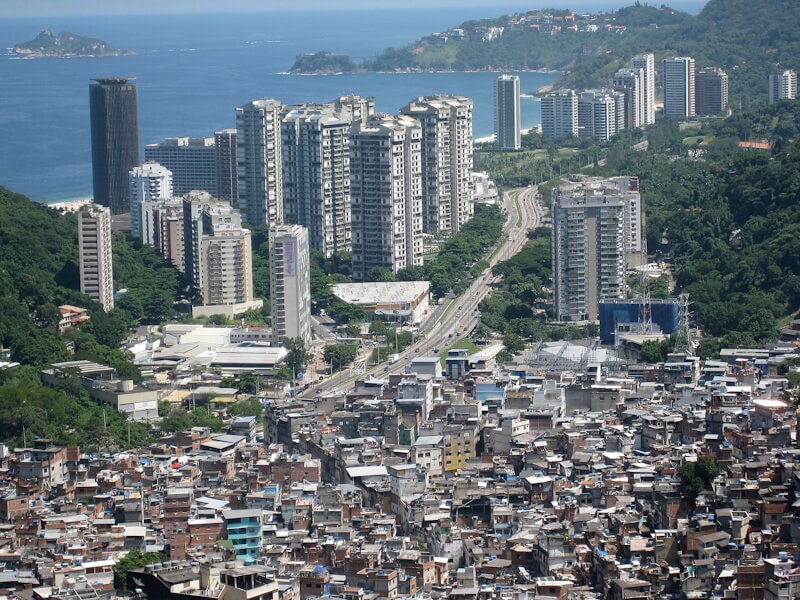

Brazil – protest and participation

The environmental struggle in Brazil has always been as much about solving local issues of congestion, social justice and poverty among others. In the chapter, ‘Grassroots Reframing of Environmental Struggles in Brazil’[22] in Henri Acselrad’s book Environmental Justice in Latin America: Problems, Promise, and Practice[23], the environmental movement in the country can be understood in two stages — ‘the phase of protest and awareness efforts; and institutionalization and participation in public policy. It starts with efforts to protect the local environment and shifts to addressing greater challenges —hazards from excessive use of mechanical and chemical techniques in agriculture, and danger to the overall ecosystem.’[24]

The United Nations environmental conference in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 gave way for the formation of a new forum, the Brazilian Forum of NGOs and social movements for the environment and development. One of the largest causes of environmental concern in Brazil has been oil extraction as well as the natural gas and biogas industries. It seems like environmental protection often takes a back seat in the face of economic benefits of extracting oil, gas, and coal; national and international news reports rarely mention the pressing environmental and public health issues.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Colombia – environment beyond capitalist numbers

By far, the most dangerous country for environmental activism, going by the killings, Colombia exemplifies anthropologist Hickel’s construction of the world’s environmentalism – countries and companies of the Global North extracting its resources often in connivance with a section of the locally powerful. Mamá Mercedes Tunubalá Velasco, from the Misak community and the first indigenous woman to become Mayor[25] of a municipality in Colombia, has stood firm and lived to tell the tale.

Besides the violent confrontation, the country has seen what she described as “planes de vida” or plans for life that the indigenous communities in Colombia have been developing, based on ancestral knowledge, to incorporate in the country’s legislation and policies. At the Johns Hopkins University dialogue, she explained how indigenous communities, particularly women, critiqued the development model of capitalism from this perspective: Capitalism gives signals of crisis where few are happy, where human life is valued in statistics and numbers and nature is commodified for profit, which is not compatible with the indigenous worldview and “planes de vida” as it does not manifest respect for all life or harmony with nature. Since the 1991 constitution, indigenous communities have more political participation and recognition in Colombia.[26]

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Vietnam – advocacy and conviction

In Vietnam, many climate activists have been jailed on the pretext of ‘tax evasion’. In the past two and half years, six prominent environmental defenders have been imprisoned. In 2019, Nguy Thi Khanh, founder and director of Green Innovation and Development Center (GreenID), became the first Vietnamese in the global list of 100 most influential people in climate policy for her advocacy of sustainable energy solutions including the curbing of coal pollution. Using scientific research, she worked closely with authorities to promote long-term, sustainable energy projects and reduce carbon dioxide emissions. However, in June 2022, Khanh was sentenced to two years in prison on charges of tax evasion. Her sentence was later reduced to 21 months and she was released in May 2023.[27]

High-profile energy policy adviser Ngô Thị Tố Nhiên, founder and executive director of Vietnam Initiative for Energy Transition Social Enterprise, has been detained since October 2023. She was sentenced[28] to 42 months in prison for misappropriating state documents. Her trial was held behind closed doors and her conviction has not been publicised in state-affiliated media. Nhiên is the sixth prominent expert working on environmental issues, particularly on the issues of energy transition, to have been arrested within two years.[29]

Nikeita Saraf, a Thane-based architect, illustrator and urban practitioner, works with Question of Cities. Through her academic years at School of Environment and Architecture, she tried to explore, in various forms, the web of relationships which create space and form the essence of storytelling. Her interests in storytelling and narrative mapping stem from how people map their worlds and she explores this through her everyday practice of illustrating and archiving.

Cover photo: Congo river; Credit: Wikimedia Commons