The world adds a billion square metres of new floor area every year – this is equivalent to a new Paris every five days.[1] This mind-boggling figure is worrying as countries face worsening effects of climate change. Urban heat islands are mushrooming owing to rapid urbanisation. With green buildings becoming the buzzword for sustainability, countries are looking at reforming and amending building laws to bring in ‘green’ changes. Recent constructions have been vying to get the green rating. There is growing awareness of energy and water-efficient structures.

The 128-storey Shanghai Tower in China is an example. Boasting the world’s tallest turbines that generate around 10 percent of the building’s electricity, it has natural cooling and ventilation. Its 24 sky gardens have earned it the status of world’s greenest skyscraper. The largest LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) Platinum certified building in the world since 2015, it collects rainwater and re-uses waste water, has a combined cooling and heating power system and uses 40 other energy-saving measures that cut 34,000 metric tonnes from its annual carbon footprint.[2]

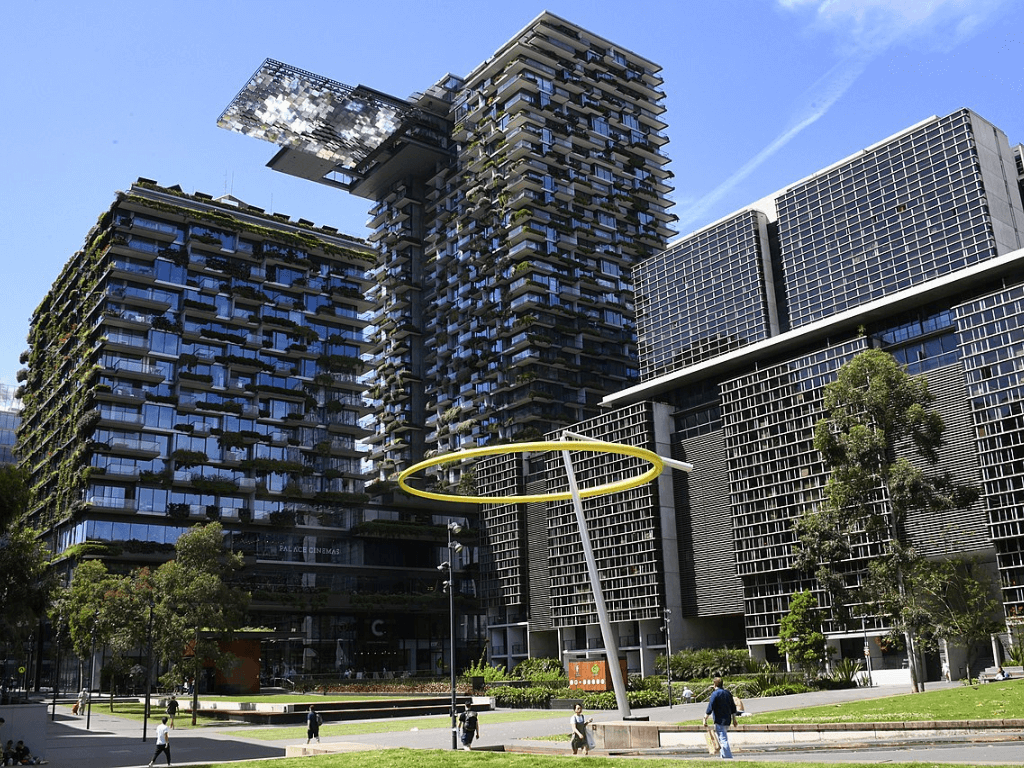

One Central Park in Sydney, Australia, (photo above) is covered with a vegetation of around 250 species of plants and flowers. It consumes 25 percent less energy than conventional buildings of the same size. Apart from these landmarks, commercial and residential buildings are making efforts to turn into net zero.

Here is a look at how other countries introduce and implement green building concepts in their construction sectors.

Australia

In Victoria, Australia, planning policies were comprehensively updated to support environmentally sustainable development and this was reflected in the lot and precinct scale developments. The Planning Policy Framework was amended and ‘responses to climate change’ was included as a new purpose of planning schemes.

It is compulsory for new developments that require a planning permit to show how their proposal reflects policies for improved energy performance of buildings, more sustainable water management outcomes, recycling and waste minimisation, sustainable and low-emission transport choices, cooling and greening of urban areas, urban biodiversity, and reduced exposure to air and noise pollution. Over 2023, the state drew up an Environmentally Sustainable Development Roadmap to support the deployment of new planning standards.

Homes include not just the structure but everything around it. This roadmap also aims to improve guidance on stormwater management to encourage the use of recycled and stormwater for tree health. By applying design standards that make it easier for households and businesses towards reuse and recycling of materials, the waste sent to the landfill can be reduced. There are also provisions to encourage sustainable transport choices, reduce heat impacts through new tree planting to cool the landscape using natural biodiversity and consequently, reducing residents’ exposure to air and noise pollution for new homes near busy transport corridors.[3]

Most Councils (local government bodies) in Victoria require a Sustainable Design Assessment (SDA) Report to be submitted with applications for Planning Permits including for alterations and additions. Councils strongly encourage the submission of an SDA Report for all other developments that fall in certain criteria. Councils require a Sustainability Management Plan (SMP) Report for developments that exceed the criteria such as non-residential development. To facilitate the process, Councils endorse a computer-based tool like Built Environment Sustainability Scorecard (BESS) or equivalent to determine if a proposed development measures up to standards of environmental and sustainability performance.[4]

A planning permit application measures the sustainability performance of the planned project. The permit is requested for the authorities to ensure that new buildings meet environmental performance standards. It highlights the environmental objectives of the Council and serves as an equitable assessment tool while also promoting the benefits of incorporating sustainability and its importance in the development process.[5]

A study titled Sustainable building and the regulatory approach in Australia found that all claims of regulation to be sustainability-based are false owing to regulatory policy conflicts.[6] It also goes on to state that the technical methodology behind the regulation swerves from the scientific method and highlights the denial of public access to data “under the guise of ‘commercial-in-confidence’ from government agencies”.

In response to the environmental impacts arising from building development, the Building Code of Australia (BCA) expanded its traditional scope of safety, health and amenity of building occupants by introducing energy efficiency provisions for residential construction in 2003. In July 2004, following a scoping study, the Australian Building Codes Board (ABCB) announced its intention to further broaden its scope by “…prioritising specific sustainability issues, including energy, water, materials and indoor environment quality”. The 2006 edition of the BCA incrementally broadened energy efficiency provisions in both the number of building classes and the stringency levels.

The study adds that “the essential meaning of sustainable building, in the context of appropriate management of the development of the built environment, can only surface by returning to root principles of sustainability.” It further elaborates that the lack of a national strategy is a hindrance in the formulation of an adequate framework for the building sector’s contribution to environmental issues like depleting natural resources, increasing emissions, and waste. This also makes it challenging to allot financial and human resources and how they should be weighed alongside social equity issues like affordable housing and shifting demographics of the aging population.

A broad national policy to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, for residential buildings, has been reduced to “little more than an exercise in building physics of predicting heat flows, solar gains and passive solar principles.” No post-occupancy evaluations have taken place, and the extent to which these regulations contribute to the reduction of carbon dioxide emissions is unknown.

Canada

The Canada Green Buildings Strategy (CGBS) has been laid out to reach the country’s climate goals, reduce monthly bills and also increase the supply of housing stock in Canada.

Canada’s buildings account for 18 percent of the country’s emissions, ranking third behind oil and gas and the transportation sectors. Equipment that runs on fossil fuels such as natural gas furnaces and builders used for water and space heating, where most of the buildings’ operating emissions come from. Also, construction materials such as concrete, steel, aluminum and wood add to the emissions from buildings. The aim of the CGBS has been to “accelerate retrofits, build green and affordable from the start and shape the buildings sector of the future” by decarbonising and improving the resilience of Canada’s building stock, supporting affordability of housing and creating jobs.[7]

Canada’s federal government, in recognition of its role as a significant purchaser of goods and services including construction services, has a policy on green procurement. It calls for an increased integration of environmental considerations in the procurement process to influence the demand for environmentally preferable foods and services. The expected results of this policy include reducing greenhouse gas emissions and air contaminants, improving energy and water efficiency, reducing ozone depleting substances, supporting reuse and recycling, reducing toxic and hazardous chemicals and substances, and supporting biodiversity. Also, the policy aims to support more environmentally responsible planning, acquisition, use and disposal practices in the federal government.[8]

The country also has a ‘Standard on Embodied Carbon in Construction’ which sets down the requirements to “disclose and reduce the embodied carbon footprint of construction projects in accordance with the commitments in the Greening Government Strategy,” which aims to reduce emissions and improve climate change resilience.[9]

Vancouver city has a Zero Emissions Buildings Plan.[10] with four action strategies. First is to ensure that the majority of new buildings in Vancouver have no operational greenhouse gas emissions by 2025 and second, that all new buildings have no greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. The strategies focus on establishing emissions limits, promoting city-led building projects to demonstrate zero-emissions buildings, catalysing developers and builders to demonstrate effective ways to zero-emissions buildings and capacity building by sharing knowledge and skills required to achieve this goal.

The United Kingdom

The United Kingdom’s oldest method of assessing, rating and certifying a building’s environmental sustainability is the Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM). Founded in 1990 by the Building Research Establishment (BRE), it provides a holistic sustainability assessment framework for buildings and infrastructure, looking at factors such as low-impact design and carbon emissions reduction, design durability and resilience, adaptation to climate change, and ecological value and biodiversity protection. It provides the tools and frameworks to empower everyone involved, from investors to operators, to make informed decisions for the lifespan of their asset.[11]

Setting a target of net zero carbon emissions by 2050, the United Kingdom leads in the development of technologies and sustainable construction principles. It is making efforts to mainstream ‘green’ and ‘pro-climate’ choices with the BRE mechanism and beyond. Examples include an attempt to move away from fossil-fuel boilers to construct buildings that are more energy efficient. Take London, its largest city and capital, which introduced the Spatial Development Strategy for Greater London called “The London Plan 2021”.[12] It sets out a framework for how the city will develop over the next 20-25 years and has whole dedicated sections on green and sustainable design and construction.

What makes the Plan effective is that it is a part of the statutory development plan, requiring policies in it, to inform decisions on new constructions and refurbishment across the capital. Several tools have also been developed to support this transition. In 2024, the Green Buildings Tool[13] took a major step by introducing features that enhance usability, precision, and security. From expanded Carbon Risk Real Estate Monitor (CRREM) analysis and advanced portfolio management tools to enhanced accessibility and streamlined integrations, these updates empower users to navigate sustainability challenges with greater efficiency.

Not only can it calculate the current values but also provide the potential status of assets over time. Using the Green Buildings Tool’s timeline feature, users can track the mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions over time and evaluate the progress of carbon performance.[14]

India

In India, green design and construction is primarily integrated through the voluntary green building rating systems. Other large parallel attempts include the Bureau of Energy Efficiency’s ‘Energy Conservation Building Code’ (ECBC) and, more recently, the Energy Conservation & Sustainable Building Code. The union Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change provides fast-track environmental clearance for green buildings which get provisional certification from the Indian Green Building Council (IGBC).

Every state has local laws to guide builders to construct green commercial and residential complexes and many states offer incentives too at local level. However, the green building rating system is voluntary in nature, leading to lower than required adoption. The continuous but slow integration of the green building framework into local bye-laws is an inhibiting factor too.

In Maharashtra, green buildings rated by the IGBC as silver, gold and platinum get an additional FSI of three percent, five percent and seven percent respectively. The Public Works Department has mandated the renovation of existing government buildings and construction of new government buildings to be carried out as per the IGBC system. Integrated townships have been mandated to obtain at least a silver rating.

Maharashtra’s Urban Development Department has notified that an incentive on FSI of three percent for Three Star, five percent for Four Star and seven percent for Five Star rated building shall be granted on submission of Green Building Certificate from GRIHA (Green Rating for Integrated Habitat Assessment).

Tamil Nadu offers a 25 percent subsidy for setting up environmental protection infrastructure that obtains an IGBC certification limited to Rs 1 crore. Similarly, data centre units undertaking green and sustainable initiatives as per the IGBC ratings are eligible for a 25 percent subsidy on cost with a limit of Rs 5 crore. As per the Tamil Nadu Integrated Townships Development Draft Policy 2022,[15] the developer needs to comply with the IGBC norms for the Integrated Township.

The Housing and Urban Planning Department of the government of Uttar Pradesh offers 10 percent floor area ratio (FAR) for projects provisionally certified as Gold by IGBC. The state’s Tourism Policy 2022-2032 offers a 50 percent reimbursement of the IGBC certification fee up to Rs 10 lakh to hotel and wellness resorts.The Greater Noida Industrial Development Authority (GNIDA) offers an extra five percent FAR free of cost for buildings certified as Gold or above by the IGBC.[16]

Maharashtra adopted GRIHA ratings for all government and semi-government structures. It is mandatory for all government, semi-government buildings, local bodies and public sector undertakings, to achieve a GRIHA rating of three stars. The government of Himachal Pradesh offers an additional 10 percent FAR to projects that have been granted 4 or 5 stars by GRIHA.[17]

Photos: Wikimedia Commons