Goa’s capital city, Panaji, at the confluence of rivers Mandovi and Zuari, is one of its smaller urban centres at just 8.30 square kilometres but exemplifies all that’s happened in the state over the past few decades – the exponential growth of tourism, rising demand for second or holiday homes from across the country, tourist infrastructure, entertainment avenues, and real estate boom that has altered the landscape especially its coastal strips. Panaji, or Panjim as some people still call it, is no longer the languid quiet un-urban place it used to be.

As Goa’s third largest city, Panaji is a coming together of the old and the new. Its high heritage value comes from the 912 listed architecturally distinct public and private buildings dating back to the 19th century; its modernity is visible in the tourism-related facilities built from the 1970s including, most recently, the casino ships. Panaji is now a major tourist hub and hotspot with a daily footfall of between 5,000 and 15,000.[1] The estimated[2] nine lakh tourists annually add to its residential count of 1.14 lakh enumerated in Census 2011.

Dealing with a floating tourist inflow nearly nine times its residential population has put immense strain on Panaji’s infrastructure and natural resources besides presenting untold administrative challenges. The Portuguese, when in command here, had built Panaji as an administrative centre. Until 1971, Panaji had a population of only 35,000 people and it retained its low-rise human-scale cityscape until the 2000s.

Panaji exemplifies Goa – the exponential growth of tourism and real estate in the past few years has brought human and ecological pressure. Tourism-related facilities such as hotels, restaurants, public conveniences, adventure and entertainment facilities have reached their peak. The growing demand for second or holiday homes, which fetch high rentals for absentee owners, has fuelled a construction boom. From 1991 to 2019, built-up areas along Goa’s coast doubled within the 500-metre coastal buffer zone, from 19.6 percent to 40.3 percent of the total area, and increased from 15 to 37 percent within the 200-metre buffer, found this study.[3]

Can Panaji, and Goa, sustain itself in the face of so much pressure and sweeping changes? Already, in parts of the city, especially old areas like Fontainhas, residents are resisting the constant influx of tourists who barge into gardens and patios to shoot photos for their social media feeds.[4]

Casinos dominate, residential character abates

Some date Panaji’s spiralling chaos to a government decision in the early 2000s, which cashed in on its pretty streetscape and natural surroundings, to locate the Goa International Film Festival and use it as a force multiplier for real estate and casino businesses. More than two decades later, the once-serene Mandovi River mouth at Panaji, cradled for centuries by sandy shores and lush green hillocks on either side, presents an altogether altered picture.

The hills are being rapidly divested of their remaining forests and green canopies as zoning manipulations bring the construction industry farther inside.[5] The mouth of the river is choked with garish neon-lit casino ships; their feeder boats frantically ferry tourists to and fro. Several government facilities, jetties, and administrative buildings near the shore are leased to the casinos as passenger and booking lounges. This has changed Panaji’s character and feel.

This transition from a heritage-rich, administrative capital to an entertainment and casino hub[6] has come at a cost to the residents of Panaji who are forced to now deal with unresolved traffic, parking chaos, and other excesses of tourism. There are 248 registered hotels in Panaji’s core city area and 136 in the outer areas, according to the tourism department.[7] Repeated pleas from residents to relocate the casino ships and short cruise boats on the Mandovi have been dismissed.

Planning policies for Panaji have, in fact, doubled down to increase the tourist footfall regardless of the load on the city. This is evident in the Smart City Mission projects in the past decade that focussed on creating tourism-related conveniences in the dense waterfront area that comprises the core city. This area used to be a mixed institutional, commercial, and residential area; it now has a high concentration of commercial activities, hotels, cafes, casinos, multi-level parking facilities, and more.

Panaji’s Revised City Development Plan 2041,[8] unveiled in 2015, recognised the immense shortage of space for the expansion of the city. As much as 25 percent of the city’s area is covered by natural resources, four percent is water bodies and four percent is under conservation[9] which means 33 percent of the city is not available for growth. Parks, playgrounds, and green traffic islands comprise a further 14.55 percent while land use under transportation and communication accounts for 5.45 percent and residential use was almost 51 percent, according to the Development Plan 2007.

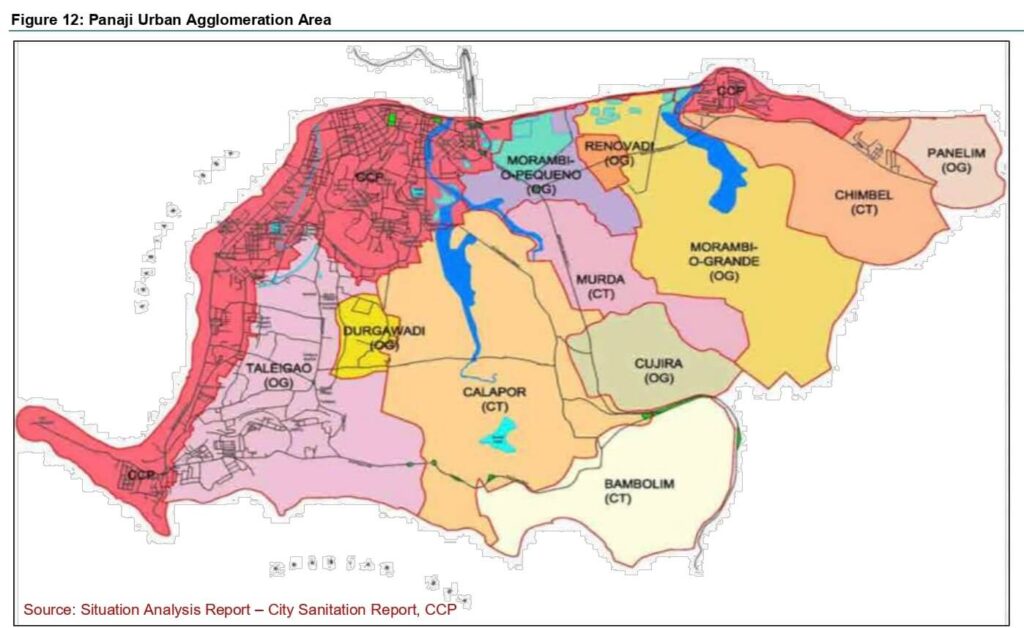

Much to the chagrin of people, recent governments opted to shift schools and government offices to satellite areas but permitted tourism, casino and commercial use in the core city, altering its character from administrative and residential to tourism-commercial. Meanwhile, Panaji’s high rents, congestion, and controlled Floor-Area-Ratio[10] [11] pushed its expansion into 11 unplanned urban areas (seven outgrowth areas and four census towns) that together cover 86 square kilometres. This suburban Panaji, governed by village panchayats, has absorbed the city’s expansion which includes premium holiday homes and speculative real estate buys, especially in the upscale Dona Paula and Taleigao plateau

Photo: Pamela D’Mello

Panaji’s flood plains

Panaji is only seven metres above sea level and slips below sea level at high tide; it was built over alluvial lands and coconut groves around intertidal low-lying areas. There’s realisation[12] now that the city’s haphazard expansion since the 1990s, which accelerated after the 2000s, has denuded its natural coping mechanisms to deal with heavy rainfall and high tides of the Mandovi River. Central to this mechanism are three creeks – Rua de Ourem and St Inez that flow through the city, and the Merces-Chimbel on its outskirts – which traditionally absorbed the run-off.

“The Portuguese administration kept proper setbacks in the catchment areas of all three creeks prohibiting anyone to build any construction close to their tidal channels,” Dr Nandakumar Kamat, of the Goa University wrote.[13] The three creeks have faced staggering construction and infrastructure activity, beginning with the Mandovi bridge in the 1970s, reclamations for the Patto commercial area in the 1980s, and continuing into the present with two bypasses, flyovers and highways that have steadily blocked the hydrology and water draining patterns, and paving surfaces has worsened it. “At present all the three lifeline creeks of Panaji are in their final stages of ecological transition…nature’s gifts of millions of years destroyed in less than 50 years,” he remarked.

Water logging[14] in Panaji is now an annual feature.

Photo: Pamela D’Mello

Natural wealth threatened, residents troubled

As a coastal and riverine city, Panjim is in an ecologically-sensitive zone, partly within Coastal Regulation Zone I, II and III areas.

These have not remained unscathed despite the best efforts by NGOs, environmentalists, and citizens. The Goa Foundation has fought several legal battles in the High Court over CRZ violations by hotel constructions in and around Panaji and construction on hill slopes. In the 1990s, it litigated against the construction of a 3.09-kilometre coastal road from Miramar to Caranzalem and Dona Paula over mature sand dunes.

“On the other side, the road which is now characterised by high rise apartment complexes and hotels, particularly, in the Caranzalem area, were once low-lying agricultural lands characterised by an abundance of freshwater”, the study[15] by Aaron Savio Lobo and Ashali Bhandari points out. A TERI study in 2018[16] identified khazan land, mangrove ecosystems, creeks, and sand dunes in and around Panaji as its natural resources that face major threats.

How have long-time residents coped with the changes? Former Panaji councillor Patricia Pinto, 68, speaks of the spread of mosquitoes including in the city’s famed Campal Children’s Park from where her grandchildren had to return in a rush. School children crossing the Mandovi have to bear degraded water quality which earlier generations did not. A recent study[17] by scientists at the National Institute of Oceanography found higher levels of polluting microbes in the mangrove-lined estuary areas in Campal, a heritage ward, and Panaji compared to similar ecosystems in non-urbanised areas of the state.

When people of Panaji find that the activities they once enjoyed are no longer safe or possible, it shows the southward trajectory of the city as a livable place even if its skyline and commerce are rising. In fact, tourism-increasing projects have seen a pushback from residents under ‘Save Panjim Initiative’ which has challenged the ropeway project, waterfront construction on the Mandovi riverbed, and conversion of recreational public space into tourist facilities.

“We have to act like watchmen of the city almost all the time to see what’s being changed for the worse. It can be very draining,” says Pinto, known for setting up Panaji’s waste segregation system. Protecting Miramar beach has been particularly daunting. “We documented the beach for nine years, divided it into nine stretches, and systematically cleaned it up with help from the then government” she recalls. Her team at the People’s Movement for Civic Action opposed several moves to use the beach as a site for tourism-related food festivals.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Diverse ecosystems and market forces

This 2019 report[18] recognises the city’s diverse ecosystems. The estuary of the Mandovi gives it a mosaic of wetlands, several beaches and coves, mangroves, three creeks, alluvial plains and a slice of the Western Ghats in its offshore province, hillocks, backwaters, sea, agro-horticultural plots, sand dunes, fresh water bodies, and intertidal zones to name some of its ecosystems. A seven-kilometre riverfront promenade and several landscaped gardens built during the colonial making of the grid-based city adds to this.

The team researching for the report found 404 species of flora and fauna, of which 27 flora and 14 fauna species were listed under the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972. The report unequivocally stated: “Wherein the Town and Country Planning (TCP) ought to be a key player in green architecture and eco-friendly landscaping, the market demands have remained pivotal in space utilisation… Often ecology and biodiversity are viewed as contrary to urban planning and design. There is a complete dearth of inter-sectoral synergy and complementation”.

Can plans help?

Citizens have raised agitations to push back against market forces altering the cityscape, including groups like the PMCA, Goa Bachao Andolan (GBA), Goa Foundation, Bailancho Saad, Save Panjim Initiative, Goa Heritage Action Group and others. Plans themselves are of little use as some of them demonstrated in 2007, during the real estate boom, when the GBA and others stalled the Regional Plan and argued for a more participatory one.

However, the real estate industry and market have managed to find their way into Panaji by having the Regional Plan altered to leave out Panaji. An Outline Development Plan 2011 was prepared for Panaji, says planner and researcher Tahir Noronha, but land-use planning for the city and high-value areas around has remained controversial and arbitrary. While the city has a series of ODPs, they ought to be a temporary device, as per best practices in planning, till legally-binding Comprehensive Development Plans are prepared but these were not, he adds.

Panaji’s ODP 2021 was challenged in the courts, for arbitrary zone changes and increased Floor Area Ratios permitting commercial zoning in residential areas, and shrinking heritage protection. Meanwhile, the khazan and salt pan areas saw construction blocking them, large mangrove areas have atrophied[19], and positive[20] initiatives like a mangrove walk have done little to help.

Sadly, its residents say, the planned grid city lost a narrow window in the 2000s to keep its growth trajectory from turning chaotic. Panaji’s growth has extracted a heavy price, indeed.

Pamela D’Mello is a senior independent journalist based in Goa. Her work focuses on social and economic issues, politics, culture, and the environment. Her writing has been published in national and international publications including Frontline, Economic & Political Weekly, Scroll.in, The Wire, Caravan Vantage, Huffington Post, Quint, Mongabay, India Today, BBC, Deccan Herald, Down to Earth.

Cover photo: Pamela D’Mello