Originating in the marshlands of Taleigao and fed by the Nagahali hills, the St Inez creek flows through the city of Panaji, tracing its geographies and drains into River Mandovi. This is not a surprise for those who are aware of Panaji’s history as a wetland before it was turned into Goa’s capital city. The creek plays a significant role in sustaining life such as draining out the water during heavy rains and bringing in the fish that sustains livelihoods.

Panaji, also known as Panjim, was possibly called Pancham Khali in which khali refers to the creeks in and around the city. The St. Inez passes through the areas of Camrabhat, Tamddi Mati Tonca, flowing behind the Military Hospital, Don Bosco School and the ESG complex. Snatches of this are seen in the documentary Avnati (Decline)[1] which traces the decline of the creek and highlights the emotional connections of the people who live around it. Made by Kabir Naik and Kuhu Saha, the 8-minute film won the People’s Choice award in the Nagari competition last year held by the Charles Correa Foundation.[2] Though focused on St. Inez creek, the film is a wake-up call about the wetlands across Goa.

Avnati makes the point that the creek is itself a resident of Panaji – a living, breathing factor that holds life within itself in the form of various aquatic species as well as memories of people who have grown up playing on its banks and crossing the metal bridges built over it. In it, Talulah D’Silva, well-known environmentalist, speaks about how creeks are important to avoid flooding during rains and for the fish catch. She remembers crossing a metal bridge across the Mandovi as a child in 1980 and recalls many marine creatures in the water. Naturalists and residents have identified species of snakes, crocodiles, otters as well as over a 100 species of birds over four-five years. Sachin Megere, a fisherman from Cambrabhat, remembers fish and crocodiles in the water during his childhood and the water being so clean that people could drink it. Over time, it has turned poisonous.

The film’s compelling Konkani background score invites viewers to sit with the stories in which gripping visuals show sedimentation, pollution and neglect in the Creek. But it also shows restoration initiatives and concludes with a call to action, reminding the community that its future lies in the future of the St. Inez Creek. “We tried to capture how urban commons can also play a role in the economy, as a space that belongs to everyone who lives there. We wanted to build the city’s connection to it and the song by Shant Shakti also follows that,” Saha told Question of Cities.

Shant Shakti is the stage name of musician Dylan D’Souza,[3] a Konkani rapper whose evocative track in the film traces the history of the Creek to his grandfather’s memories, and how it has degenerated due to concretisation and construction.

From creek to other water bodies

The heavy sedimentation in the St. Inez Creek impacts its capacity to drain water into the Mandovi. When Panaji receives rain, this means that the threat of flooding in areas around the Creek is magnified. The film captures this through the voices of residents – people finding it difficult to navigate outside their immediate surroundings, people relocating away from the St. Inez Creek, and so on. “Besides this, many casinos in Goa are being built on the seafronts or along water bodies adding to the burden,” Saha says.

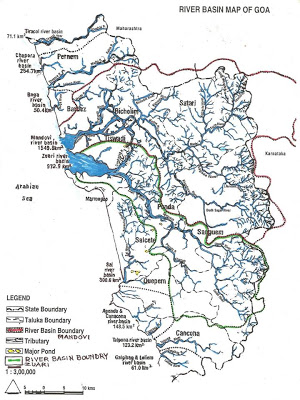

The 11 rivers across Goa – Mandovi, Zuari, Mandre, Sal, Galjibag, Saleri, Colval, Talpona, Terekhol, Baga, and Harmal – together nurture 42 tributaries which are sources of potable water and support several ecosystems. Most of the rivers originate in the Western Ghats and drain into the Arabian Sea. Along the way, the rivers form an intricate system of wetlands, tidal marshes, and paddy fields which are further connected by canals, inland lakes, bays, lagoons, and creeks. Pollution from mining and construction around a creek – or any water body in this ecosystem – means havoc in the entire system.

Besides the pollution from mining, the discharge of untreated wastewater and industrial effluents into the streams is cause for concern.[4] The increase in settlements and constructions on riverbanks has also adversely affected the riverine ecology in a state where rivers are a part of people’s customs, traditions and lifestyles.[5]

In July 2024, the government’s Water Resources Department (WRD) tested 112 water bodies and found that nearly 60 percent were polluted – from Goa’s first Ramsar site of Nanda Lake at Curchorem, which is also one of Goa’s largest wetlands and the habitat for birds like black-headed ibis, wire-tailed swallow, bronze-winged jacana, brahminy kite, intermediate egret, red-wattled lapwing, and lesser whistling duck, to Carambolim Lake which welcomes migratory birds from Eastern Europe. The list of polluted water bodies included wetlands like the Bondvoll Lake at Santa Cruz, Batim Lake at Goa Velha, and Toyaar Lake.[6]

In their film-making, Naik and Saha found that the St. Inez Creek used to be wide enough to be used as a navigation route within Panaji. “We tried to capture the history of the Creek. It was a rich local biodiversity spot with different birds visiting it. It also had crocodiles which have held a lot of importance within Goa’s culture,” says Saha.

Photo: SANDRP

Pollution as poison

The untreated sewage, industrial effluents, and commercial waste from hotels and buildings nearby are to blame for the degradation of St. Inez Creek. The industrial belt of Taleigao-Panaji where it flows, has hotels and restaurants that groan from the influx of tourists. The high E. Coli content shows human excretory waste too. The filmmakers also found that the records show a much wider St. Inez Creek; its narrowing can be attributed to construction.

The Goa State Pollution Control Board (GSPCB) has been monitoring the Creek and testing samples on 29 parameters. Back in July 2014, a study found raw sewage contamination including increased levels of faecal coliform. The reason for high sewage in the creek water is said to be because many dwellings along the creek do not have a sewerage system[7] but the question is what the authorities have done in the past 10 years to stem the contamination.

The increased pollution and contamination have affected people living around the Creek, especially the fishing communities, and there has been a rise in dengue and malaria cases.[8] Saha says the filmmakers were advised against entering the creek water as it would be harmful to skin. Residents point to the 90 toilets, sewage treatment plant, and slums along the 3.5 kms stretch of the Creek. Authorities have attempted to clean the water body but to no avail.[9]

While cleaning is important, the focus should also be on regulating the waste let into it. The film has suggestions from people to stop all construction or create a buffer area. Both, people say, will allow biodiversity and wildlife to regenerate. However, the official plans head in the opposite direction – more construction and concretisation to create seating areas, walking tracks, and restaurants to “transform” St. Inez Creek. The Imagine Panaji Smart City Development Limited is currently working to stabilise the banks and renovate bridges.[10] Like standard “beautification” projects, the focus here too is on turning the Creek into a pretty place – far from allowing its natural habitat and beauty to flourish.

The film is significant in that it records people with fond memories of swimming in St. Inez and going to the opposite bank – an impossibility now. People recall floating paper boats into clear water and walking alongside them on their way home from school. And it inspired many like Savio Fonseca, author of ‘Photographic Guide to the Birds of Goa’[11], who grew up watching birds there. He has been involved in many conservation and eco-tourism projects across Goa. “I have seen around a hundred species of birds and fish, turtles and crocodiles, snakes and mammals, also otters and mongooses. The condition of water bodies across Goa ranges from terribly polluted to very pristine,” he says, echoing that Goa’s natural areas show the same problems as in other states.

The relationship of people with the Creek now is starkly different. In a spatial sense, it’s a place to avoid. When people build homes, they no longer want to face St. Inez; when near it, most people look away. The film captures these emotions well and points out that despite rejuvenation attempts, not much has happened on the ground. Since the film was released, trash booms were installed under the bridges to segregate the waste but there’s nothing to confirm that the wastewater discharged is now being treated.

Goa’s khazans under threat too

Not only the St. Inez Creek but Goa’s ancient water systems like the khazans have also fallen prey to the prevailing narrative of development that disregards ecology. “Khazan land is very important because Goa is a historically reclaimed land. The indigenous communities built the khazans as an interconnected system of sluice gates and bunds for farming and pisciculture. There is a lot of salt water, so they have salt-resistant crops alongside pisciculture. Through a lot of trial and error, they found a balance,” says Saha, who was also part of the team that made another film on the khazans.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The khazan ecosystem is recorded to have played a role in preventing soil salinisation and conservation of biodiversity besides providing food security for millenia.[12] The impact of climate change coupled with neglect, mismanagement, and commercialisation of land and fishing rights threaten the existence of this ancient ecosystem.[13] Like other indigenous communities overrun by urbanisation, the people here too see ancient practices being erased.

The Goa Khazan Society, an organisation of people and experts working to preserve what’s left, believes that this climate-resilient practice can be just the panacea that Goa’s water systems need. It can provide food security and show the path to sustainable water management. Elsa Fernandes of the Khazan Society of Goa says, “The khazan ecosystem made it possible to do farming and fishing despite the salty waters. Goa’s Coastal Zone Management Plan was notified in 2022 in which the Khazan Land Management Plan is a mandatory item. It’s an important step towards preserving this system which can help us fight the effects of climate change.”

Elsewhere, in areas like Mollem, the trees and their entire ecosystems are under threat requiring the intervention of people to save them. The filmmakers found that the land there is prone to inundation if the trees go. Goa, a fragile ecological state but rarely seen as such, needs people to step in to protect it – activists to ring-fence trees, forests, creeks, rivers and more as well as filmmakers and storytellers who can tell their stories far and wide.

Nikeita Saraf, a Thane-based architect, illustrator and urban practitioner, works with Question of Cities. Through her academic years at School of Environment and Architecture, she tried to explore, in various forms, the web of relationships which create space and form the essence of storytelling. Her interests in storytelling and narrative mapping stem from how people map their worlds and she explores this through her everyday practice of illustrating and archiving.

Jashvitha Dhagey is a multimedia journalist and researcher. A recipient of the Laadli Media Award consecutively in 2023 and 2024, she observes and chronicles the multiple interactions between people, between people and power, and society and media. She developed a deep interest in the way cities function, watching Mumbai at work. She holds a post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic.

All photos, except where indicated, are stills from the documentary Avnati.