India’s cities could be designed better and, where not possible, redesigned to make them more accommodating of people’s needs. Redesigning breaks barriers in some ways, small and seemingly insignificant perhaps, but can mean exponential relief and comfort for people. Changing municipal rules to keep parks open throughout the day like Bengaluru did, making streets car-free even though only on weekends or for a few hours every day, implementing one-way streets, reimagining a city’s watercourses to create parks long them, repurposing old factories and hangars into cultural venues and so on are some of the tinkering we have seen recently.

The triggers could be any. After the gang-rape of a young woman in 2013 in the abandoned Shakti Mills Compound in the heart of Mumbai, citizens’ groups came together to transform the Shakti Mills lane into a safer and vibrant zone. Women have held ‘reclaim the night’ events at the Bandra Kurla Complex which tends to get deserted at night. Redesigning and recreating people-centric spaces makes areas fluid and welcoming, and also strengthens people’s relationship with their surroundings in cities.

Mumbai offers far less open space per person at 1.1 square[1] metres on average than say New Delhi at 21.52 square metres[2] per person and London at about 31.68 square metres[3] per capita. Every day, nearly 7.5 million people use Mumbai’s suburban rail network, its lifeline, with massive footfalls at station entrances and exits round the clock. On the roads outside every station, chaos reigns as millions struggle to find space to walk, haggle with auto rickshaws, queue up for buses while dodging street vendors and parked vehicles. The need to improve these spaces seems a no-brainer. Redesigning areas and streets outside railway stations would immediately offer a more comfortable commuter experience.

Over the past year, we, at Walking Project, have strolled on dozens of streets, recorded the movements on them, observed and studied areas across Mumbai. We have analysed the flow of people and vehicles, the presence of hawkers, and usage patterns by retailers at their storefronts, and had interactions with rickshaw and taxi drivers among others. In this essay, we take this work forward by redesigning three locations that are currently problematic for pedestrians.

Mumbai Central: Decluttering public spaces

Mumbai Central station is a significant terminus for both outstation trains and the suburban network, serving around 3.5 lakh[4] people every day. Flanked by some of the city’s wealthiest neighbourhoods on one side and some of its derelict infamous ones on the other, the entrance-exit points pose numerous problems for pedestrians. The west side of the station has hardly any walkable spaces and the chaotic public spaces here discourage people from loitering or waiting.

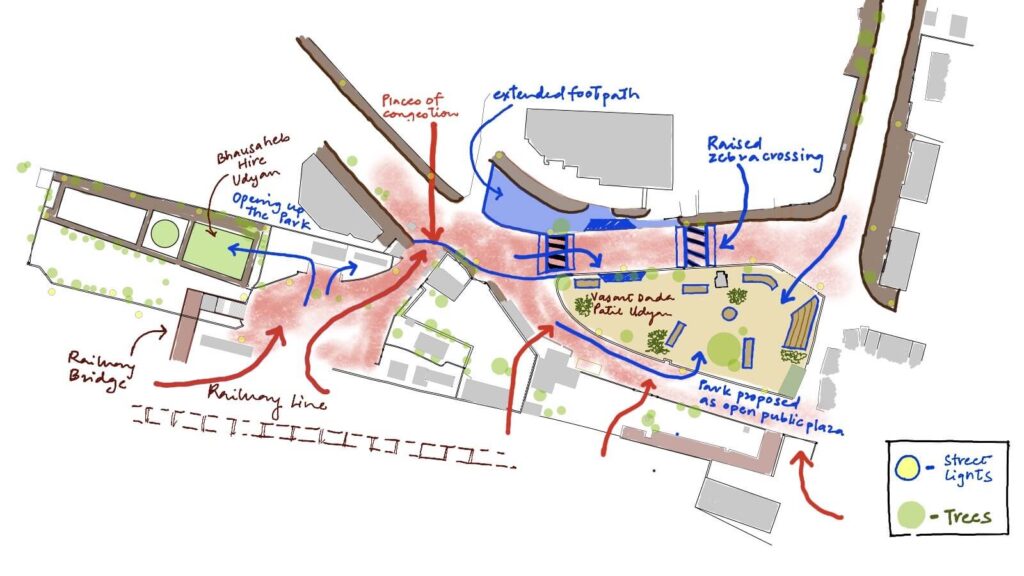

When you exit the station via the middle bridge, you are led to a narrow walkway squeezed between rail tracks on one side and Bhausaheb Hire Udyan on the other. The park remains closed most of the day, limiting access to 9-5ers and ignoring the needs of others like delivery workers, house helps, and students who can use its shade and green throughout the day. The exit leads to a disorganised intersection dominated by parked taxis, the footpaths are not walkable because they are occupied by vendors or used for two-wheeler parking. In some sections, there are no footpaths. Pedestrians have to navigate through this maze twice a day, every day that they use the station.

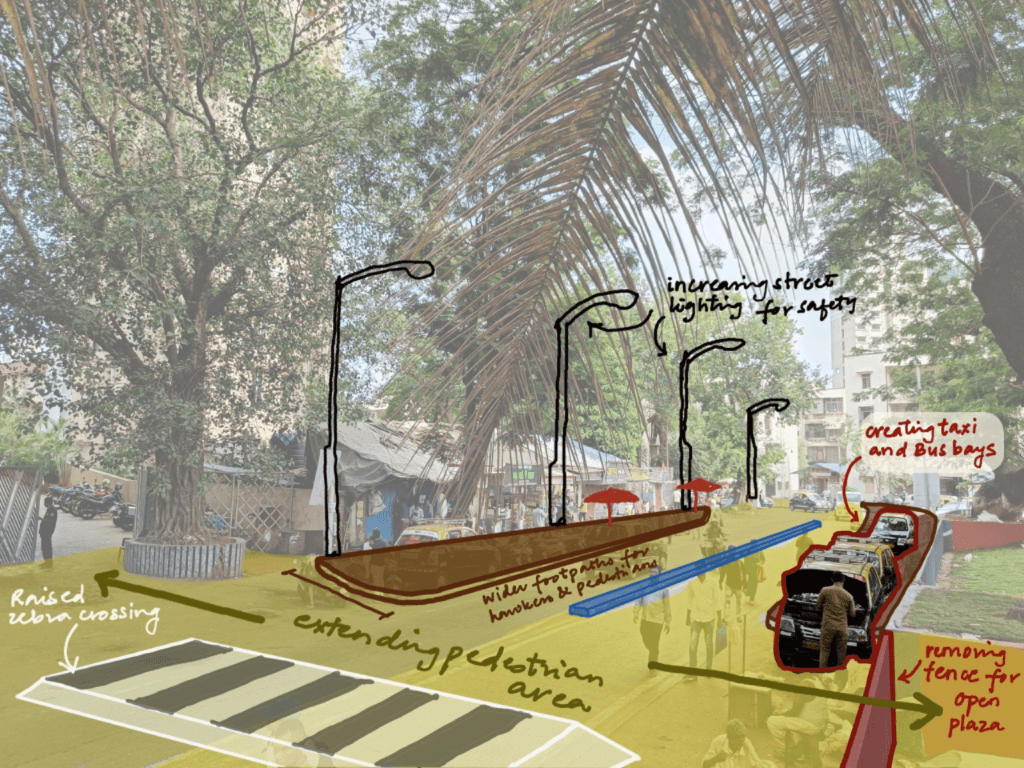

Our vision for the area is to redesign it so that it becomes an inclusive and accessible space for all. The narrow walkway should be resurfaced and kept free of impediments. The footpaths should have space for pedestrians at all times. The Bhausaheb Hire Udyan can be a flow-through park with seating for people to take a break before they scramble for trains; extending its open hours would maximise its utility. Adding an amphitheatre will create a dedicated space for gatherings right outside a key railway station.

For women’s (and general) safety, simple improvements such as better lighting would help, especially in the dark. The Vasant Dada Patil Udyan, a large triangular park north of the walkway which is fenced, can be redesigned as an open public plaza with a shaded seating area, designated taxi bay, and a bus depot which is now a five-minute walk from the station.

In fact, the localities around with a number of old and dilapidated buildings may undergo redevelopment soon which opens up the entire area for redesign. In such a situation, building public parking facilities adjacent to the station would reduce on-street parking and keep pedestrian movement free of encumbrances, or wider and properly designed footpaths can accommodate hawkers in designated areas along with clear pedestrian lines. Traffic-calming elements, such as raised zebra crossings and consistent carriageway widths can make the precinct clutter-free and welcoming – which means safety, accessibility and comfort for all.

Dadar: Reducing vehicular traffic

Dadar is Mumbai’s Gordian knot both for the volume of commuters it facilitates and for the utterly chaotic entrances-exits it has. As a key railway station and an interchange point for both Western and Central railway lines, Dadar sees a combined footfall of nearly 10 lakh every day. Of this, around half use the Western Railway[5] Dadar also handles about 18 long-distance trains every day.

The streets outside Dadar are a nightmare come true on any given day. Crushload volume of pedestrian movement, high volume of vehicular traffic, bustling markets with shops as well as vendors outside every shopfront, parked vehicles, organic waste from vegetables and flowers that it’s known for are all elements that people jostle with as they walk out of the station area to their destinations or bus stops. Wide footpaths have not helped because they are occupied by vendors, the high footfalls drawing them here. The daily average footfalls are set to increase after the Metro Line 3 begins operations.

Ranade Road, perpendicular to the station, known for its iconic shops in the area, is a microcosm of the dizzying chaos outside Dadar station. The 600-metre stretch to Lady Jamshedji Marg is so congested with competing uses that pedestrians are forced to walk in the middle of the road. Noise levels are consistently high given the incessant honking. There is an urgent need for redesign here to make movements seamless within the framework of shops and vendors – a complex urban challenge.

The critical element of redesign here is to take all vehicles off Ranade Road given the high pedestrian volumes round the clock. A pilot project could be initiated by completely blocking the road by using barriers, as it was done in Delhi’s dense Chandni Chowk, and adjacent roads opened up alternately for one-way traffic. The median could be redesigned for regulated hawking through an auction process, with its proceeds allocated for corridor maintenance including waste management and staffing marshals.

Thoughtful street furniture, improved signages, and more trees planted will enhance the road. For residents and businesses that require vehicular access, exceptions could be made through an ID card system. Pick-up and drop-off points for private vehicles and taxis, which frequently block movement, could be demarcated on side streets. These are some of the many redesign possibilities. If done as a pilot, the redesign of Dadar’s Ranade Road could become the template for many of the 37 stations on the Western Railway and 62 on the Central line. Congestion and chaos do not have to be normalised.

Mulund: Reclaiming pedestrian space

Mulund, among the older and greener suburbs of Mumbai in its north-east, falls on the Central Railway line. During our street mapping project, we covered over 25 kilometres of the suburb on foot to map its walkability and mobility patterns. Mulund’s unique grid layout provides multiple alternative routes for vehicles to reach any location, creating a significant opportunity for pedestrianising streets without disrupting traffic flow. However, the station area is a typical chaotic space with vendors all over, narrow footpaths, and heavy commuter footfalls.

Based on our work, Walking Project envisions redesigning the arterial RRT Road along the lines of Chennai’s Pondy Bazaar. Widening footpaths to cover 60 percent of the road, reclaiming space for pedestrians, providing designated areas for hawkers, heavily regulating street parking can help facilitate pedestrian flow and support livelihood needs. The redesigning interventions can be for auto rickshaw stands, raised crossings for pedestrian safety, improved drainage near the station to eliminate puddles, street furniture, drinking water kiosks, seating spaces and greenery, and a better signage system. The bus stops in the station area, currently scattered and insufficiently covered, could benefit from larger and weather-protected shelters which give information about routes and bus movement updates.

The redesign, or reallocation of space, may be radical considering that a footpath now covers 15 percent of the road width and another 25-30 percent of the road is occupied by hawkers’ merchandise and customers, pushing pedestrians to walk in the middle of the road. Redesigning the area would enhance the experience for all stakeholders involved. Many concepts from Dadar’s Ranade Road can be applied here to ensure a balanced and user-friendly environment.

Shakti Mills lane: Changing image

In 2013, the derelict Shakti Mills Compound in Mahalaxmi, became infamous for the gang-rape of a young photojournalist. The lane in which the out-of-work mill stands too has old factory-style buildings repurposed into retail centres and offices, even an art and cultural space. The latter, G5A, and the women’s advocacy group Akshara joined forces to launch the initiative Reclaiming Shakti “to reclaim this area as a space that is not only accessible and safe, but also becomes an exemplar and a ‘model’ enclave; one that is inclusive, proactive and culturally vibrant”.[6]

The Shakti Mills lane is frequented by nearly 2,000 office-goers and 300 visitors each day, many of them women. Crumbling walls, debris along the lane, inadequate street lights, and unauthorised taxi parking give it an air of unsafety besides posing hurdles for pedestrians. G5A and other operating businesses and institutions in the area were collectively recognised as the Advanced Locality Management (ALM) body by Mumbai’s municipal corporation. Together they created an action plan to define places, provide unobstructed view of signage, reduce visual clutter, vehicular and pedestrian wayfinding, and allow for fluid transitions. Signage at entrances and on the street, installing lights and increasing the green cover in the neighbourhood were the first steps to transform the lane.

They also suggested initiating a dialogue through public art-based initiatives to dispel the negative perceptions about the area. “Art would thus become a medium through which larger conversations and initiatives around safety, liveability, creativity, and other driving forces of our lives can be,” states the report.[7]

People-centric public spaces

The redesign recommendations are a radical shift in how road space is allocated in Mumbai. The current approach — widening roads to accommodate vehicles — overlooks the fact that only a small percentage of people travel by private cars and that last-mile connectivity matters to millions. The vast majority walk but have the least – almost unavailable – space. Buses, which offer last-mile connectivity from virtually every railway station, do not always have facilities for drop-offs near stations. To create a truly liveable and inclusive city, the radical mindshift needed is to prioritise people over vehicles, and prioritise public over private vehicles.

Our proposed redesigns attempts to make key areas of the city more people-centric public spaces, accommodating the needs of pedestrians as well as vendors and ensuring vehicular movement. Redesign is not a difficult mountain to climb nor does it call for large resources – only imagination and the intent of authorities to put people at the centre of the spaces. A more equitable, people-centred design is not just necessary — it’s the way forward for Mumbai.

Vedant Mhatre, activist with the Walking Project, passionately explores the complexities of the modern urban landscape, focusing on urbanism, transportation, and climate issues. Adept at crafting online campaigns to drive attention to urban challenges, he creates and uses informative videos on these topics to drive home the point. He holds a bachelor’s degree in Electronics Engineering.

Nikeita Saraf, a Thane-based architect, illustrator and urban practitioner, is now with Question of Cities. Through her academic years at School of Environment and Architecture, she tried to explore, in various forms, the web of relationships which create space and form the essence of storytelling. Her interests in storytelling and narrative mapping stem from how people map their worlds and she explores this through her everyday practice of illustrating and archiving.