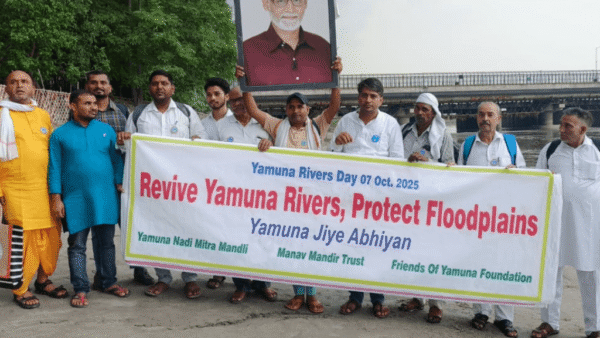

The Silkyara-Barkot tunnel story made India hold its collective breath in November last year. Located in Uttarkashi, Uttarakhand, the under construction tunnel partially collapsed, trapping 41 workers for 17 days. This was not the first time the tunnel, part of the 900-kilometre all-weather Char Dham road project, had caved in but it brought to the fore the many lapses and warnings that environmentalists had flagged off. The Char Dham road project had apparently sidestepped the crucial Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) study.

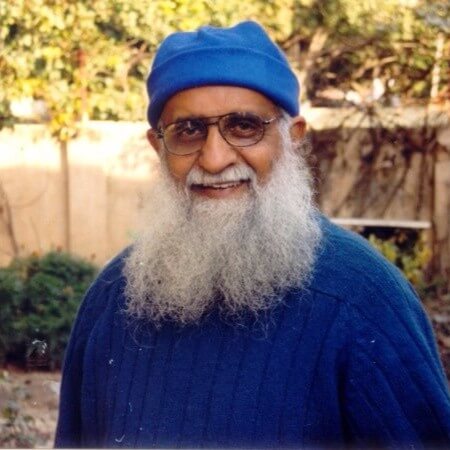

The incident highlighted the fragile mountain region and the massive construction spree which is arguably making the region unstable — something that environmentalists like Ravi Chopra had been warning about even before work started. Chopra, as the chair of the high-powered committee on Char Dham road widening, had objected to the proposed width. When his recommendation to limit the road to 5.5 metres was overruled, he resigned. This act of resistance was widely lauded but the central and state governments went ahead with the construction.

Road-widening projects cutting through the mountains financed for as much as Rs 30,000 crore till 2018,[1] and a slew of hydro-electric power projects including the one near Joshimath have turned controversial because of their ecological impacts. In September 2020, Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurated six mega development projects in Uttarakhand under the Namami Gange Mission.[2] Ahead of the LS polls this year, the centre released Rs 559 crore for 33 infrastructure projects.[3]

Chopra’s role is much sought after as Uttarakhand lives through this development spree. His rich background as a research scientist at the People’s Science Institute along with his focus on environment and development has made him an active campaigner to protect the region and ensure its sustainability. He has helped set up several organisations in the social and development sector that work on livelihoods, disability rights, human rights, water resources management among other issues. Chopra spoke to Question of Cities about protests and activism that goes beyond just saving the environment.

Why is resistance needed in cities at different levels, by various kinds of people?

Sometimes resistance is needed because some basic duties that need to be performed by government authorities, whether it’s the municipality or the state government or the central government, are not being done. There are protests about that. Sometimes, there are resistances to issues that the public feels are detrimental to the environmental well-being. This has been the case with the Aarey Colony in Mumbai and also the merciless cutting down of trees in Dehradun for large-scale projects.

You resigned from the high-powered committee opposing the widening of the Char Dham road beyond 5.5 metres as it would damage the ecology. Why don’t we see more such resistance to protect the environment?

It has come to me as a major surprise that people valued my action because I thought that what I did was routinely necessary. I did not think of it as a very big thing. First, I had a point of view, which was in the minority. There was an official government’s point of view, which was in the majority. The court had mandated that in case of disagreement, there should be a vote. I did what the court said – and lost. But then, I felt the issue deserved the court’s strong attention. My minority point of view was the correct point of view. So, I wrote a special box item, a paragraph in the report, pointing this out. I urged the court to apply its mind to this part and it was accepted.

Later, the government resisted and, after many challenges, worked things out conveniently and got the judgment in its favour. At this point, I realised that along with getting the judgment in its favour, it also appointed a committee of a former Supreme Court judge. I felt that if this committee is going to do the oversight, what are we going to do? I felt no purpose there. My main goal was to try and save as much of the Himalayan environment as possible. We were getting nowhere, I thought it was a pointless exercise, so I quit.

I’m quite into activism these days.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

What made you take up full-fledged activism and how did you start?

The current phase of activism started in May 2022. In December 2021, the Hindu Dharam Samsak had called meetings calling to get rid of the Muslims in the country. Some friends approached me and asked me to bring together a bunch of eminent people in the city to protest this. So, I did that and we got a good bunch of people to sign the letter that we drafted to the chief minister. It made headlines in all the newspapers.

After it was published, the Superintendent of Police visited me, trying to inquire what all I knew and so on. That’s when I decided that enough is enough. What is the use if a citizen doesn’t have the right to speak up. Then, I launched the Uttarakhand Insaniyat Manch and, in 2023, I decided to join hands with the Bharat Jodo Abhiyaan, an umbrella body of civil society platforms..

The goal is that in seven years, we will challenge the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and build a strong counter to it. This is the biggest challenge before the nation and that it should not be neglected. Since then, I have been involved in the activities of the Bharat Jodo Abhiyan and I have been trying to bring in as many people together to share concerns.

We started working with women in Dehradun against the drug proliferation in the city and the state. We are, of course, working with environmental activists against the rampant cutting of trees in the city and in the valley, and working on issues of human rights. All these issues are connected and all are resisting or protesting something valuable to life.

What were the tactics or strategies you adopted?

Initially, it was a general kind of call to friends and known people, asking them to come and brainstorm, but eventually it was more. What distinguishes all these activities is that there is a focus at the ground level. I want to make sure of that. For example, we organise a rally in Dehradun with women’s movements against drugs almost every Sunday morning. We join the women’s groups and go to a locality. They talk to the women there in small group meetings. We walk through the streets, we hold street corner meetings and talk to people. The focus is on the ground-level activity, directly talking to people of the area and trying to understand their reactions.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

How can we have better or positive resistance so that it makes an impact?

One of the important things in all such work is not to treat your opponents as enemies, to not bring in the elements of hatred or dislike, but see them as people who have opposing points of view. So, our approach is that we meet officials and try to dialogue with them. Often, they try to show that they are also equally concerned and attempt to carry out some positive action, but policy change is very difficult.

A day before the tree-felling protests on New Cantt Road a few weeks ago, the government put up hoardings saying that no trees will be cut for this road and that the government will encourage citizens to take up tree plantation in their neighbourhoods during the forthcoming Harela festival. But the government backed out very quickly.

I also work with Citizens for Green Doon that has been holding various protests since November 2020, probably before that too. We have planned another major protest against a proposed dam just outside Dehradun city limits. A lot of trees are being cut for the water treatment plant. More trees will be submerged in the dam reservoir. We have to protest and we have to resist this.

What other issues does the Manch look at?

The Uttarakhand Insaniyat Manch holds public meetings on social issues. We invited the well-known lawyer Prashant Bhushan last December. Before that, we had invited Justice (retired) Madan Lokur. At these meetings, the numbers of people who attend keep rising and we hope that our other campaigns and messages go through to them as well.

We were, of course, a part of major protests through this year against the cutting of trees in Dehradun. After the protests, the likes of which this city had not seen before, the authorities said that they will not cut the trees in a certain section but the road-widening work is going to continue. People and groups will have to keep resisting. See, people do turn up when they perceive the issue as serious. In April 2022, there were about 600-700 people who came out to protest cutting of trees for the Delhi-Dehradun Expressway. This year, hundreds came for the protests.

We had also organised a protest with Raghavan and Sanyal Manch, and the Mahila Manch, against the brutal killing of the three women in Manipur. Around 600-700 people had come out to protest. That’s a huge number for Dehradun.

In November 2020, an organisation which was almost relatively unknown then, had organised a protest march along with others against the cutting of trees for converting the Dehradun airport into an international airport. I was not involved in that but I read newspaper reports stating that around 600 to 700 children had joined that protest. There is action and resistance on the ground, that’s what works.

Shobha Surin, currently based in Bhubaneswar, is a journalist with 20 years of experience in newsrooms in Mumbai. An Associate Editor at Question of Cities, she is concerned about Climate Change and is learning about sustainable development.

Cover photo: QoC file photo