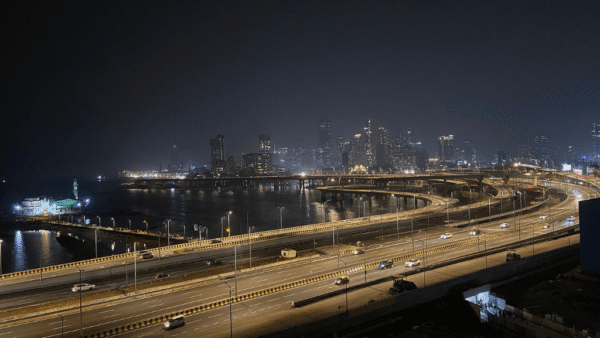

Till the year 2000, when the JJ Flyover was constructed on Mumbai’s Mohammed Ali Road, Chirodeep Chaudhuri made several trips by BEST bus route 3 Limited, grabbing his spot on the front window seat. The well-known photographer and city chronicler wanted to get the perfect shot of the famed Mohammed Ali Road before the flyover “cut through the neighbourhood” for the late historian Sharada Dwivedi’s forthcoming epochal book on the city’s history. More than two decades later, Chaudhuri found himself capturing similar frames of Worli seafront and Haji Ali dargah before the coastal road took them off our everyday landscape.

“I’m already lost in this new city, getting onto the coastal road bridges, going off in directions I didn’t intend to,” Chaudhuri says. He is fascinated by the city that is constantly being made and unmade – and remade. “In the next 15-20 years, the coastal road would be complete and people would have forgotten that there was a time when the sea was visible at Worli-Haji Ali, when there was no Bandra-Worli sea link, when there was a view from the Bandra Fort.”

Cities transform all the time, in small and mundane ways and in sweeping strokes, in a continuum. A time-lapse would show how much a city has changed because we miss a turn that’s now different, see buildings that did not exist, chance upon old photos, or read stories that allow the old city to shine. Resisting these changes is impractical and untenable. Except for a few precincts that are purposefully marked as heritage, landscapes in most cities change as their socio-economic character transforms over time.

Documentation and archiving, compiling stories, organising walks, study circles, going back in time to explore and understand a city as it used to be become forms of resistance against the inevitable erasure of cities. Remembering and reliving parts of the erased city are, indeed, acts of resistance against erasure. This can take the form of organised institutional projects but is not greatly valued in contemporary India’s cities.

Recording, remembering and reliving resists the idea that a city can be scrubbed completely clean of its character, built environment, and vibe to accommodate a new one. Remembering as resistance is common in conflict zones where a people and their land are being obliterated but, in a decidedly less violent context, it can be true of cities too as they transform. Across India’s cities, chronicling, walks and story-telling are underway to remember cities that they used to be – warts and all. All acts of resistance.

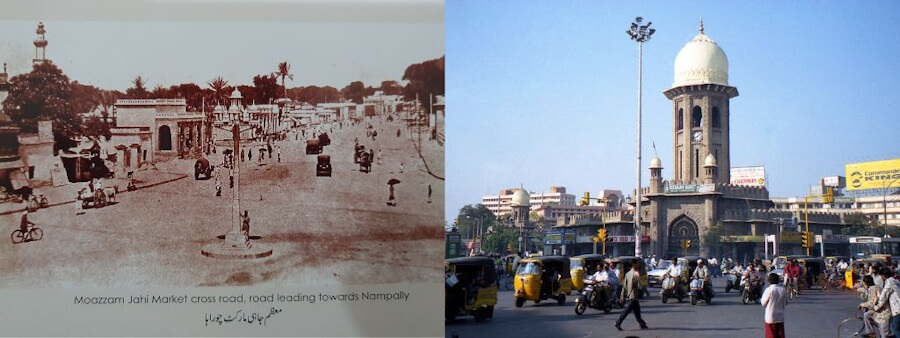

Photos: Yunus Lasania and Wikimedia Commons

Sepia tones of cities

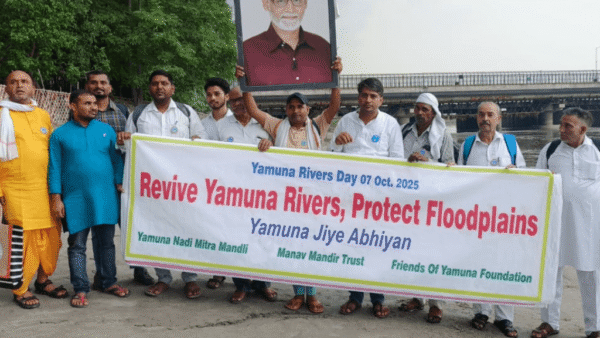

Journalist and oral historian Yunus Lasania started the Hyderabad History Project in 2017 to make historical information about his home city accessible through objects and spaces hidden in plain sight. There is history beyond the Golconda Fort, he wants people to know. He leads groups to places like the historic Moazzam Jahi Market built in 1935 that is still a buzzing busy market and tells stories not of kings but folks not documented in history. “People would not leave Hyderabad if they knew its story,” he says.

Experiencing the living traditions of cities can bring people together, says Mariam Siddiqui of Delhi by Foot, who conducts walking tours in the national capital. “Walking in groups allows people to access and experience practices of different communities through visits to places like the oldest temple and dargah of Mehrauli in a walk. Once people are more aware, they can make connections, change the way they look at history,” she explains.

Siddiqui emphasises the need to engage with local cultures so that they are not entirely forgotten. Highlighting Phoolwalon ki Sair, a Mughal tradition which saw a revival by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru in the 1960s, she says, “If more people retrace the path of this festival, it may bring the government’s attention.”

Walks across cities like Agra[1], Lucknow[2] and Bengaluru[3] focus on different aspects of city life and inevitably end up chronicling the food, architecture, communities, and even literature from these cities. Sketching Collective, a group based out of Hyderabad conducts workshops and sketch walks in monuments.[4]

Photo: MS Gopal

Life photos

A city’s present is also material for documentation. Chroniclers use various media to record life in cities as it is lived focusing on everyday life. MS Gopal, a photographer by passion, is known for his quotidian photographs of Mumbai that are not news but stories worth sharing. The city is his homeground but it is always changing. And he wants to capture it.

“Our roads are always being dug up, old buildings are demolished and new buildings come up. It’s a constant flux. Capturing Mumbai is like trying to capture a cloud; it is never static,” he says. Along railway lines and the congested traffic on streets is where he finds most of his photo-stories. “How cars occupy spaces like playgrounds and what people go through while commuting in public transport are great stories to tell when the talk is all about more roads and cars. Somebody has to tell this story, right?”

When old buildings are bulldozed by the predatory forces of capitalist land values, keeping them alive in popular imagination is resistance by creating memories. Homes with verandahs, porches and little gates of their own are a dream amidst Mumbai’s highrises. Bandra has, or had, several of them in every lane. Shormistha Mukherjee, media professional, writer, and a long-time Bandra resident took to chronicling them, mainly on social media.

“The owners of these old and beautiful houses say that tempos to carry large articles like refrigerators can’t enter these lanes, neither can ambulances, and they want water for 24 hours. They are not wrong,” Mukherjee explains. As people change, so do neighbourhoods – the other way around too. She wants to capture as many old houses as possible before they are demolished. She has seen porches disappear where fisherwomen sold fish and customers shared recipes with them, so also village squares which were people’s meeting points, and the in-between spaces.

“The boundary wall was such that you were letting the outside come in and the inside get a glimpse of the outside,” Mukherjee says. She started a newsletter last year to document the oral history of Bandra’s residents, talking to older ones about their life. She has come across beautiful photos of the suburb before it ‘reclaimed’ the sea. “People know Bandra Reclamation, not what was ‘reclaimed’ to build it. There were fishing villages there that don’t exist anymore…Nobody here talks about the loss of the sea but I’ve had people approach me with their stories since I started this project.”

Mumbai’s fisherfolks, the Kolis, and their way of life have been systematically erased by development. While some resisted the coastal road as it hurt their fish catch, others like Parag Tandel and Kadambari Koli founded the Tandel Fund of Archives to document and share about the community and culture. “As artistes, we devised ways to bring our stories into the limelight…Our museums and documentation are our medium of protest,” they write.[5]

Delhi-based archaeologist Anica Mann documents the city’s houses that were built between the post-colonial era and 2011, when a new housing regulation dictated that all houses have to be built on stilts. “After the death of the courtyard, some houses still had wells. Can you imagine how high the water table was in a metropolis like Delhi,” she asks and adds that these houses, built before liberalisation and the digital revolution, showcase designs based on locally available materials like terrazzo tiles.

Photo: Anica Mann

Cities of imagination

Cities have been immortalised in various books but writers have also chronicled specific areas of cities. Writer-translator Shanta Gokhale’s Shivaji Park, My Own Mazgaon by Captain Ramesh Babu, Swapna Liddle’s Connaught Place and the making of New Delhi and Chandni Chowk, and Cubbon Park by Roopa Pai all bring alive these neighbourhoods. The writers bring out their unique character when areas are being flattened and rebuilt identically.

Researchers Divya Ravindranath and Apoorva Saini started an online archive[6] in 2023 called ‘Cities in Fiction’. It is a directory for all cities documented in fiction writing and now lists about 300 cities. Ravindranath says “Fiction records the history of a particular moment in time. Amrita Mahale’s Milk Teeth, Rohinton Mistry’s A Fine Balance on the theme of housing in Mumbai are not academic but they tell you how a city is organised spatially, socially, economically and how the city has moved over a period of time.” Fiction can be viewed as an alternative archive of information. Citing one of her favourite authors, she says, “Ambai, whose work the younger generation may not know, is deeply feminist and has an interesting take on cities.”

The digital space has made available stories from cities in bite-sized but memorable formats. Social media handles like Mumbai Heritage[7] and The Paperclip[8] share interactive posts and quizzes that invite people to engage with cities from an earlier era across sports, law, culture and so on. Karwaan heritage, a student-led collective,[9] is making history accessible and engaging through social media, and organises walks in cities across India. Pages like The Karachi Walla are popular in India too.[10]

Noted urbanist Saskia Sassen highlighted the network of global cities that are “not geographically proximate and yet intimately linked to each other,” allowing for a flow of not just capital but also rich and poor migrants who contribute to the formation of ‘local’ subcultures. This, she argues, has bridged the global north-south divide.[11]

The ‘local’ subcultures in global cities are new ways to see cities. But there’s also the aspect of cloning cultures across cities – characterised by men in similar suits getting the same coffee in every city of the world. Resistance by remembering becomes significant. “Hyderabad was one of the few cities that was globalised in the 15th and 16th centuries,” says Lasania. The city is dotted with milestone markers from the Golconda period. Lasania says that most people are unaware but documentation and story-telling save the day. “How do you understand a city if there is nothing left of it,” he asks.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

The language of remembrance

Resistance can also be about reinstating or resurrecting the erased, as it were. Names of cities across India have been changed in the blink of an eye and names of areas within cities even faster. What’s in a name? The story of Muziris has an answer. The lost port of Muziris was brought back to life when[12] the Kochi-Muziris Biennale enabled the city’s story to make a home in people’s consciousness back in 2012. It showcased an installation, Black gold, taking from historian Romila Thapar’s description of pepper which was traded in thousands of tonnes between Kerala and Rome through Muziris when Kochi was not yet imagined.[13]

“The present exists because of the past,” says Dr Manjiri Kamat, Associate Dean, Faculty of Humanities, University of Mumbai. Documentation is necessary to avoid complete erasure of the contribution of people who shape cities, she explains. “It is not just about the built architecture but also culture that forms a part of the city’s fabric. Wiping out certain institutions can cause an identity crisis if the subsequent generations don’t know what happened.”

Mumbai’s mill areas were hubs of community life and culture where spaces such as khanawals (boarding houses), folk songs, theatre groups, and festival celebrations like Ganeshotsav formed the fabric of the area, and shaped social reform and freedom movements. Kamat says, “The 1982 textile mill strike was one of the largest in history. These stories need to be told to the present generation because those cultures of resistance, whether of women or workers or anti-caste movements, are also being erased under the new towers.”

Chaudhuri’s forays took him into documenting clocks in public places across Mumbai – a relic now but a key marker of an earlier era. The project has been on for 28 years and he showed at an exhibition too. He says, “There is a distinction between photographing the city intentionally and the city getting inevitably documented while being photographed…Documentation happens so we are able to access the past in our future.” He calls upon city-makers to set up organised archives. Documenting, archiving, and recording are not only resistance against erasure but, as MS Gopal eloquently described, they “can move the needle towards empathy”.

Jashvitha Dhagey is a multimedia journalist and researcher. A recipient of the Laadli Media Award consecutively in 2023 and 2024, she observes and chronicles the multiple interactions between people, between people and power, and society and media. She developed a deep interest in the way cities function, watching Mumbai at work. She holds a post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic.

Cover photo: Mumbai’s changed skyline by Chirodeep Chaudhuri