In the documentary Slum Bombay made in the late 1980s, narrated by actor Shabana Azmi when she was a housing activist, there is a clip of the then young architect Hafeez Contractor. He passionately argues for making Mumbai’s real estate sector and building profession “more liberal, much more liberal” and assures that he could turn around the city and make it free of slums “in four years, just four years”. Echoing Contractor, who would go on to make his signature buildings and the open township in Powai, was the then municipal commissioner of Bombay, K Padmanabhaiah. Arched against this view of liberalisation in housing was the then chief of Mumbai Housing Area and Development Authority (MHADA) Prabhakar Kunte, backed by housing activists and, importantly, slum dwellers themselves.

It is fascinating to watch the half-hour documentary[1] nearly 35 years later. Made at the height of the city-wide agitations against slum demolitions and debates over resettling slum dwellers in the then fast-expanding Bombay, the documentary by Ralli Jacob, Rafeeq Elias and PK Das is instructive in a time-lapse way. Within a few years, the new economic policy of 1991 formally introduced liberalisation and privatisation including into the housing sector. Fast forward to 2023, about three decades after liberalisation was ushered in which made private-developer-led redevelopment the most sought-after currency in the real estate market. Going by Contractor-Padmanabhaiah’s faith in liberalisation, Mumbai’s housing crisis and slums should have been history.

This is hardly so. Even three decades later, the percentage of people in slums is twice that in 1991; the redevelopment of old buildings, cessed buildings and chawls has happened in a piecemeal manner with no regard to carrying capacity of their surroundings and amenities, and, the idea of cluster redevelopment (a group of buildings rather than individual structures which can potentially yield more liveable spaces) has been tossed lately between state governments led by Uddhav Thackeray and Eknath Shinde.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

The redevelopment saga of Mumbai was primarily determined by Clause 33 of the Development Control Regulations (DCR) 1991 based on the Development Plan then. Its 24 sub-clauses detailed every aspect of what could be redeveloped in what way but they also allowed wide room for interpretations and case-by-case application. The latter made redevelopment into a fragmented and deficient process, unmindful of the larger plan for the city.

In particular, Clauses 33 (7) for clusters and (10) for slums have been the favourite tools for the real estate lobby. To it, the redevelopment model meant increased Floor Space Index (FSI), or the area constructed as a ratio of the plot size on which it stands, which it used to construct for-sale apartments or offices in return for providing tiny houses to slum dwellers for free. The government had effectively passed on its responsibility to provide affordable houses to individual builders and privatised the sector in one swoop.

Nearly half of the city’s population lived in slums and another 20-25 percent in old buildings and chawls; the redevelopment model applied in such a large measure completely changed Mumbai’s landscape. Central Mumbai where towers replaced low-rise chawls and textile mills is but one instance; across inner areas of south Mumbai such as Girgaon and Kalbadevi, redevelopment has wreaked havoc on narrow streets and fractured communities which lived there for generations. In old villages or gaothans, it threatens heritage precincts. Redevelopment, in the form and manner applied in the past years, has transformed the landscape and skyline of Mumbai – for worse.

A failed model, more “slummification”

Redevelopment received a boost with the Shiv Sena-Bharatiya Janata Party government taking charge in 1995. It set up the Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) which patted itself for the “innovative concept of using land as a resource and allowing incentive Floor Space Index (FSI) in the form of tenements for sale in the open market for cross-subsidising the slum rehabilitation tenements to be provided free to slum-dwellers”. Definitive research studies are yet to come by but anecdotal evidence shows that the SRA’s “innovative concept” has hardly served its purpose.

The redevelopment model has led to pencil-thin luxury skyscrapers dramatically changing Mumbai’s skyline, creating housing for the upper class and high net worth individuals on land that used to have slums; slum dwellers are “rehabilitated” in self-contained tiny tenements of around 225 square feet in the smallest corner of the plot with barely three metres between buildings. Sunlight hardly reaches the lower floors and tenements as this story showed[2]. Added to this, lakhs were displaced to accommodate massive infrastructure projects and allocated houses in similarly ill-equipped colonies in areas which already had large slums and extremely poor civic amenities such as Mankhurd, Govandi and Dindoshi.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

“The serious problem with 33(10) is that in its present form, it does not stipulate any requirements for the ground space allocation on a plot to the sale component and the rehabilitation component of slum rehabilitation projects. Typically, therefore, developers squeeze the rehabilitation construction into a small fraction of the plot leaving the balance for sale buildings. Thus, if the slum component of the project is housed on just 25-30 percent of the plot, the real density of the slum subplot will be three to four times higher than the existing slum. The sale component of the project does not usually give access to amenities such as open spaces, gardens etc to the slum rehab building. The density of housing in these subplots thus becomes up to four or five times the original density of the slum agglomeration. Further, DCR 33 relaxes what should be unnegotiable requirements of open spaces and consequently life safety, light and ventilation requirements for tenements,” pointed out this study[3] echoing many others.

This redevelopment model was flawed to begin with; developers smelt massive profits with this division of a plot. With most of the land area in Mumbai built upon and hardly any greenfield development possible, most construction activity in the last two decades has been through redevelopment. It may have provided some slum dwellers shelter as a tiny tenement with a matchbox-size washroom inside, but housing is more than mere shelter; it did not provide for basic amenities including open spaces even continuing the unhealthy atmosphere of slums and related health hazards[4] Overall, it must be termed a failed model. Mumbai’s tragedy is that it became part of the housing policy of successive state governments in Maharashtra since 1991, irrespective of the ideology of political parties.

Slums improvement?

The concept of redevelopment has been most often applied to slums or informal settlements. The mistaken notion was that slums occupied precious land in a land-starved city; in reality, informal settlements occupied less than eight percent of the city’s land. Redevelopment has yielded tall towers where slums used to be – plush and well-planned ones for sale, substandard and less-endowed ones to rehouse slum dwellers from the plot. With this template tuned to the needs of the former, redevelopment has led to unjust and awkward lives for the latter.

Data shows two other disturbing trends. One, while redevelopment has been touted as a one-stop solution for slums, only eight percent have been redeveloped in the past decade. The authorities had redeveloped 1,53,635 of the 11.35 lakh slum houses before the Census 2011, according to the Maharashtra Economic Survey 2022-23; between 2012-13 and 2022-23, only 91,660 of the remaining were redeveloped.[5]

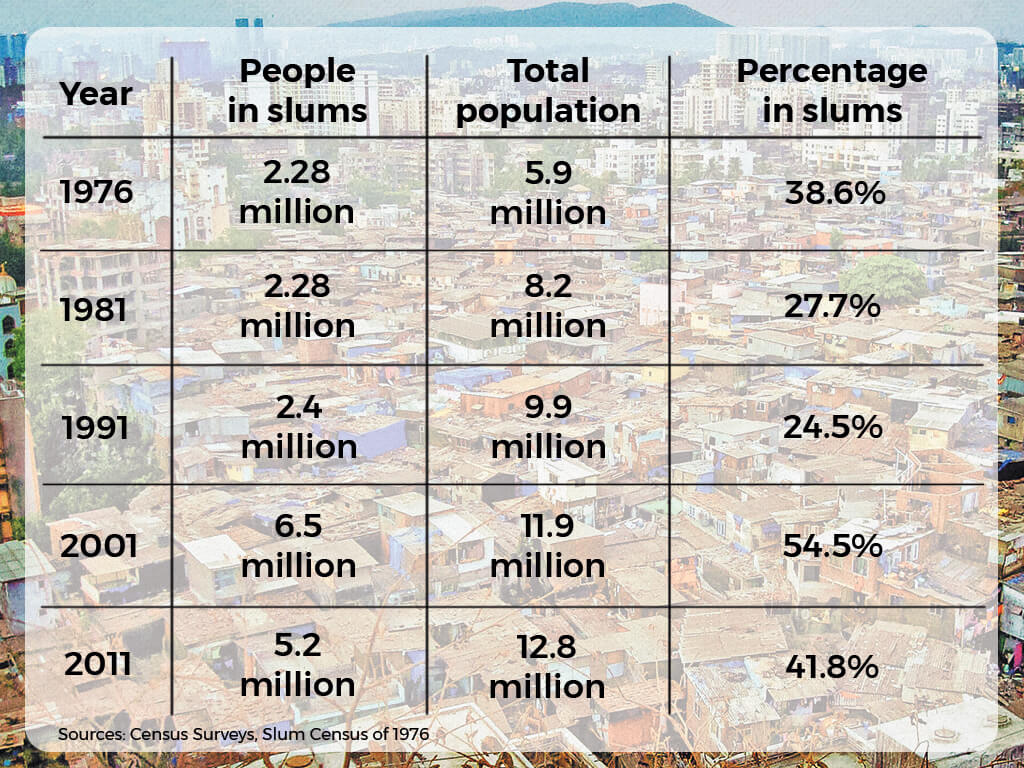

Two, the redevelopment has not dramatically reduced the population in slums but has led to the monetisation of slum land. The 1976 Slums Census, the first one done purposefully, showed that nearly a third of the city lived in slums, informal settlements and pavements. It was a tad lower in the 1981 Census at around 28 percent living in slums but this could be explained as a difference in approach by different agencies. The 1991 Census showed nearly 25 percent of the 9.9 million in the city living in slums.

Graphic: Shivani Dave

In the next ten years – the decade that saw liberalisation and redevelopment gather momentum – the percentage living in slums doubled to 54.5 percent and then showed a marginal drop in the 2011 Census. The Census 2021 data was not collected but the civic body and housing rights activists estimate it to be around 45 percent at least. Given that redevelopment has been the route to monetise land for high profits, it can be safely said that liberalisation and private developer-led redevelopment – touted as magic bullets – have hardly resolved Mumbai’s housing question.

The lure of FSI and TDR

The redevelopment model rests on two pillars – Floor Space Index (FSI) or the ratio of built-up area to the size of the plot and Transferable Development Rights (TDR) which allow builders to construct higher in lieu of land given up in another area. The FSI, also known as Floor Area Ratio or similar descriptions, is a standard metric to delineate how much can be built so that building density and population density can be aligned with the infrastructure in an area.

The FSI in the island city was fixed at 1: 1.33 and in the suburbs at 1:1 in Mumbai’s Development Plan and read into the subsequent Development Control Regulations since. However, the FSI for redevelopment was a bonanza with 2.5, 3 and even 4 in some cases. This meant builders could construct towers that rose higher into the sky without accounting for road space, water and sanitation capacity, gardens and open spaces, and so on. Builders, corporate think tanks and a section of architects have consistently argued for FSI of 8 or above in Mumbai, citing the example of New York where the FAR is 15. What they conveniently skip is that New York allows such a high buildable area in only a few zones, and that too after a due process of aligning infrastructure and adequate consultation with local communities.

The TDR was introduced in 1991, not coincidentally. It essentially allowed builders to “trade” in rights to construct more wherever they wanted to. Over the decades, it has given us odd terms such as “road TDR” and “slum TDR” where a developer would have “bought the rights” to construct higher than the permitted FSI in a redevelopment project. “Slum TDR” has been used from slum-intensive areas in say Kurla or Khar in suburban Mumbai to construct higher structures in central Mumbai.

Used in tandem, they were twin blows to the city. Additional FSI granted on a case-to-case basis loaded with TDR which builders could buy from various sources – are now supposed to buy from the massive Dharavi Redevelopment Project – had adverse implications for the city such as high building density. The TDR turned out to be a financialised FSI; the purpose of higher FSI, as in New York, was achieved without changing the base FSI level, as urban researcher Sukriti Issar eloquently pointed out in this interview.[6]

This has led to an unsustainable situation as in central Mumbai where massively tall towers in gated complexes are situated along a road that was meant for half the population. In other parts, this has led to a high building density but relatively lower population density as new constructions are mostly super-large luxury flats housing fewer people per square foot than the chawls or slums demolished from the plot.

The recent instance is in Grant Road behind Bhatia Hospital. The old Chikhalwadi chawl, a set of nearly half a dozen low-rise buildings with long galleries on each floor and a courtyard in between them, occupied a two-acre plot. Chikhalwadi was falling apart. The redevelopment, inked recently, is supposed to house all the old residents but that’s incidental; the focus is on the plan for India’s tallest residential twin towers at 312 metres, each with 61 habitable floors, and a total of nearly 13 lakh square feet.[7] The road outside Chikhalwadi is barely 9 metres wide and water supply in the area is problematic. How was this redevelopment sanctioned?

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

Government abdicates role

The reason governments love the redevelopment model as much as builders is not hard to find. Politicians have held out redevelopment as a chimera, one-stop remedy, to millions in slums and chawls. It allows the government to “show” that the city’s housing crisis is being addressed without working out a comprehensive policy through consensus and participation – which involves fractious and tedious work – but claim political loyalty of “beneficiaries” during elections.

It also allows governments the space and opportunity to patronise builders – the real estate sector itself – in a mutually-fulfilling relationship. It is no secret that builders and real estate corporations have enjoyed proximity with power in successive state governments. By diminishing the role of the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation – which has elected representatives of people – in the redevelopment process and empowering the SRA where unaccountable bureaucrats and government-appointed chiefs lead, the control of the state is near-complete. People with grievances knock on SRA’s doors – to no avail. The redevelopment model comes under a further cloud as an increasing number of politicians are invested in the real estate business or are builders themselves.

What is clear is that the liberalised free market version of redevelopment has failed to provide adequate, affordable and quality housing in large numbers. Equally clear is that the state cannot abdicate its responsibility on housing and leave it to the market. “There is an acute need to look beyond the existing tiny schemes-centric intervention. A comprehensive agenda for the overall development of slums through a time-barred mission should be formulated with higher allocations for the overall development of water and sanitation facilities…It is necessary to have an improved governance structure and processes at the institutional level so that significant policy benefits reach end-users/beneficiaries,” pointed out this research paper.[8]

The redevelopment model, flawed in its present form, matters because it has become the template across the Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR) where nearly 38-40 percent of people live in slums. In the Thane Municipal Corporation alone, one third of the people are in slums.[9] The mistakes of Mumbai should not be repeated elsewhere.

Cover photo: Smruti Koppikar